To the Editors:

It is good to see a writer with the authority and insight of Amos Elon offer his support to the consensus of many scholars of German Jewry and other visitors to the new Jewish Museum Berlin that a great opportunity for an important exhibition, in Mr. Elon’s words, “at the heart of the city where the Holocaust was conceived and administered” has been squandered by the museum’s leadership [NYR, November 15, 2001]. But there are several points in Mr. Elon’s article, particularly as it proposes to deal with an exhibition on “Two Millennia of German Jewish History,” that require some comment and even correction:

- The gala opening, including the concert by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Daniel Barenboim, took place on September 9, not September 8.

- The Guadagnini (not a Guarneri) violin played by CSO concertmaster Robert Chen in the Mahler Seventh Symphony indeed had been played by Alma Rosé (not Alma Rosè as the article has it), the Jewish violinist (1906–1944) who was murdered by the Nazis at Auschwitz-Birkenau. But Rosé was not “gassed at Auschwitz on April 4, 1944,” as Mr. Elon writes, rather, she died from general poor health, possible meningitis, and malnutrition all hastened, perhaps, by botulism from some bad tinned food served to her, absurdly, at a banquet (!) given in her honor by the Nazis to salute her work as leader of the “Girl’s Orchestra of Auschwitz.” According to Alma Rosé: Vienna to Auschwitz by Richard Newman with Karen Kirtley (Amadeus Press, 2000), Josef Mengele himself was brought in to attend Alma Rosé following this possibly accidental poisoning and the young woman’s body was actually laid out on a bier following her death.

- Mr. Elon does not mention the true significance of the connection of the use of this violin, discussed at great length in the concert’s program book: the violin belonged to Alma Rosé’s father, Arnold Rosé (1863–1946), founder of the Rosé Quartet and concertmaster of both the Vienna Court (later State) Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic for fifty-seven years from 1881 until his dismissal two days after the Anschluss in 1938, close associate and friend of Mahler, and the husband of Mahler’s sister, Justine, who was the mother of Alma Rosé. (Alma Rosé was named for Mahler’s wife, the legendary Alma Mahler.)

-

The museologist whom Mr. Elon quotes in reference to the Daniel Libeskind building is Michael S. Cullen, not Michael Cullin. Mr. Elon also does not mention the key reason, in the eyes of most observers, for the failure of the Jewish Museum Berlin to present an exhibition on the highest level—the departure of the museum’s deputy director and chief operating officer, Tom L. Freudenheim, and the dismissal of Mr. Cullen as chief of research for the exhibition project in the summer of 2000 following the death in January 2000 of the museum’s senior consultant, Shaike Weinberg, developer of the Museum of the Diaspora in Tel Aviv and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and the hiring in April 2000 of Ken Gorbey, developer of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (the so-called “Maori Museum”). The German-born, American director of the Jewish Museum Berlin, W. Michael Blumenthal, justified these changes at the time by saying that he was not developing a museum for “the intellectuals, the historians, or journalistic snobs.” Mr. Gorbey later brought on his fellow New Zealander, the novelist Nigel Cox, as director of “visitor experience.” Neither Mr. Gorbey nor Mr. Cox is trained as a historian of Germany or Jewry, nor does either of them even speak German.

-

A “scholarly catalog” may indeed be in preparation, as the first footnote to Mr. Elon’s article indicates, though for reasons that Mr. Elon makes abundantly clear, it is hard to understand how such a work could make sense of this hodgepodge of an exhibition, which barely even differentiates between original materials and reproductions and whose wall labels are woefully lacking in basic information and sometimes lacking altogether. A lavishly illustrated 224-page hardcover companion volume to the exhibition (Geschichten einer Ausstellung) is published by the museum (in both German and English editions) and has been available in the museum shop at least since September 10.

Those planning a visit to Central Europe to see an important institution dedicated to the history of the Jews might instead visit the far superior Jewish Museum Vienna. In the last several years, with a far smaller facility and a much smaller budget, the Vienna museum has mounted a distinguished series of exhibitions and published an important series of scholarly catalogs that deal with exactly the ambiguities, conflicts, ironies, and missing pages of history that Mr. Elon rightly finds so lacking in the new permanent exhibition at the much-ballyhooed Berlin museum. The Vienna museum’s Web site may be visited at www.jmw.at.

Andrew Patner

Chicago, Illinois

Editors’ Note:

Through no fault of Amos Elon’s, the Guadagnini violin discussed in his article was mistakenly identified as a Guarneri.

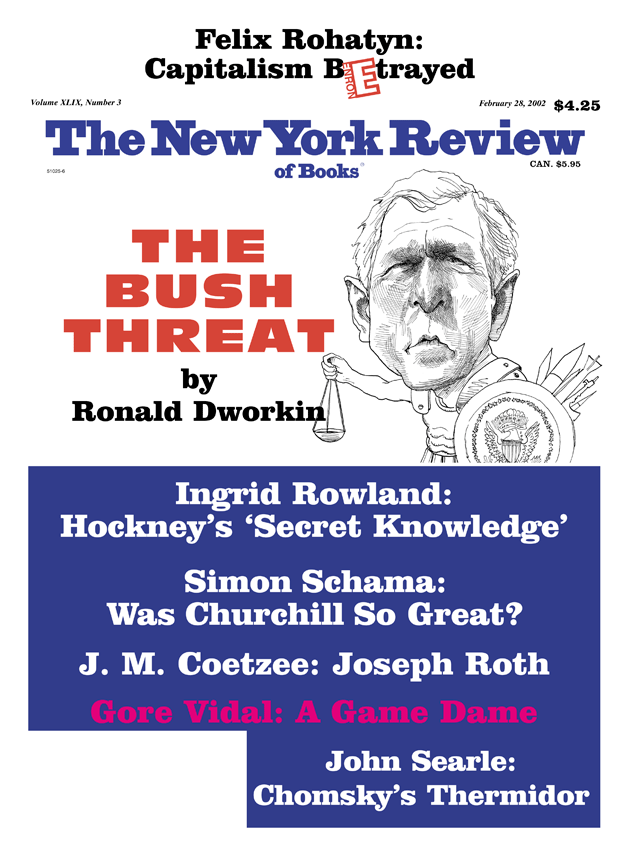

This Issue

February 28, 2002