As one of the great determining events of English history, the Protestant Reformation has never ceased to be the subject of passionate controversy. In his Acts and Monuments (better known as the Book of Martyrs), the sixteenth-century Protestant John Foxe portrayed the break with Rome, the dissolution of the monasteries and chantries, and the dismantling of Catholic worship as the triumph of godliness over anti-Christian corruption; it was a return to the simplicities of the early Church, whose traditions had been revived in the later Middle Ages by John Wycliffe and other proto-Protestants; persecuted as heretics by the Catholic Church, they triumphed, when godly monarchs rallied to their cause.

The alternative view was set out by Foxe’s contemporary, the exiled Catholic priest Nicholas Sander, whose Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism was posthumously published in 1585. Sander attributed the break with Rome to the desire of the tyrannical, lustful, and sacrilegious King Henry VIII for a divorce from his wife, Catherine of Aragon, which would enable him to marry Anne Boleyn, who, so Sander claimed, was really the King’s daughter by one of his mistresses. The Reformation which followed was motivated not by godliness, but by greed for Church lands and goods.

Those initial exchanges set the pattern for later debate. In the ensuing centuries, Protestants argued that the Reformation was a popular response to the corruptions of the Church of Rome, whereas Catholics condemned it as an act of state, imposed by selfish rulers upon an unwilling populace.

By the twentieth century, with the growth of academic history, standards of argument had become intellectually more demanding. If religious polemic was to convince, it had to meet the requirements of modern scholarship, supposedly impartial and value-free. But behind the footnotes and learned apparatus, the old attachments were still there. The study of the Middle Ages has always attracted Roman Catholics, just as Anglicans have been drawn to the history of the Church of England, Nonconformists to the study of Puritanism, Quakers to the annals of Quakerism, and atheists to the history of the Enlightenment. A modern Catholic is bound to feel resentment when visiting a medieval church originally designed for Catholic worship but now occupied by Protestants whose Tudor forebears tore down the rood screen, smashed the stained-glass windows, whitewashed the wall paintings, and defaced the statues of saints.

It is not surprising that those schol-ars who have portrayed the Reformation as a state imposition upon a reluctant people have tended to be Cath-olics, like the abbot and future cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet, who claimed in The Eve of the Reformation (1900) that “up to the very eve of the changes, the old religion had not lost its hold upon the minds and affections of the people at large”; or the histo-rian J.J. Scarisbrick, who asserted in The Reformation and the English People (1984) that “on the whole, English men and women did not want the Reformation and most of them were slow to accept it when it came.”

Conversely, those who have emphasized the spontaneous growth of Lollardy and Lutheranism have, unsurprisingly, tended to be Protestants, like E.G. Rupp, author of Studies in the Making of the English Protestant Tradition (1947), A.G. Dickens, whose pioneering study Lollards and Protestants in the Diocese of York, 1509–1558 (1959) was followed by his masterly synthesis, The English Reformation (1964), and Diarmaid MacCulloch, who has recently published fine books on Thomas Cranmer (1996) and the Reformation under Edward VI (1999). Christopher Haigh, whose influential English Reformations (1993) embodies a view of pre-Reformation England not all that different from that of Cardinal Casquet, is unusual among defenders of late medieval religion in professing what he calls “a kind of Anglican agnosticism.”

Just as Haigh’s book was going through the press, there appeared a new and impressive contribution to the long-running controversy. This was The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580 (1992) by the Cambridge University historian Eamon Duffy. If this was Catholic apologetics, as some claimed, then it was apologetics at an unprecedentedly high level. Duffy painted an eloquent and moving picture of late medieval parochial religion, vividly evoking its ritual symbolism and visual imagery. He drew on a vast range of sources, from wills, sermons, and churchwardens’ accounts to poems, mystery plays, wall paintings, and stained glass; and he made especially effective use of the evidence provided by the surviving fabric, sculpture, and decoration of East Anglian churches. His argument was that the English Reformation violently disrupted a religious life notable for its “vigour, richness, and creativity.” This message was enthusiastically received by “revisionist” historians of the Reformation, who, like Christopher Haigh, had already been arguing along these lines; it also appealed to aesthetes and art historians horrified by the spoliation and vandalism which accompanied the fall of the medieval Church.

Others were skeptical. Duffy’s account of parish religion was an idealized one. Underplaying local, temporal, and social differences, it portrayed late medieval Catholicism as rural, timeless, and consensual.1 It ignored the role of the state in persecuting heretics and defining orthodoxy. It said very little about contemporary heretics, like the Lollards, and it never paused to ask why many former monks and friars should have become convinced Protestants. Lutheranism was mentioned only once. The Stripping of the Altars was a flawed masterpiece, rich in imaginative sympathy for some forms of religion, but tone-deaf to others. It also had a polemical purpose, for as Duffy later explained, “If the Church of England was established against the will of the majority of the English people, its historic claim to be the Church of the nation does seem to be less securely founded.”2

Advertisement

Now Duffy is back again with what he calls “a pendant” to his earlier book. It is a study of the effects of the Reformation upon the tiny village of Morebath, in North Devon, on the southern edge of Exmoor, a sheep-farming community with a hundred and fifty inhabitants, and a little church with a saddle-backed tower.3 This is a topic which he first broached in The Stripping of the Altars and subsequently developed in a longer essay.4 His decision to make a book of it is amply justified.

Duffy’s primary source is a remarkable set of parish accounts, maintained by the man who was vicar of Morebath from 1520 to 1574, Christopher Trychay. A Devonshire man, he never went to university, but he was numerate and knew Latin. Hundreds of English churchwardens’ accounts survive for the Reformation period, but the Morebath accounts are special, offering what Duffy calls “fifty years of uniquely expansive and garrulous commentary.” Published in 1904 by J. Erskine Binney, a former vicar of Morebath himself, they are well known to students of the period.5 But Duffy has gone back to the manuscript in the Devon Record Office and has made some new discoveries.

To understand the Morebath accounts, it is necessary to appreciate the distinctive structure of the village’s devotional life. This revolved around the large number of images in the parish church: one of the church’s patron, Saint George; one of Jesus; two of the Virgin Mary; and one each of Saint Anthony (healer of men and farm animals), Saint Sunday (a sabbatarian emblem), Saint Loy (patron of smiths and carters), Saint Anne (a barren woman, miraculously made fecund), and Saint Sidwell (an Exeter saint introduced by Trychay). Burning before most of these images were “lights”: candles, tapers, or lamps, each maintained by a separate “store,” or fund, raised from the sale of wool from designated flocks of sheep, from the proceeds of “ales” or entertainments, and from gifts and bequests.

These stores were administered by wardens, usually two, elected annually. The stores for the images of Jesus and Saint Sidwell, and for the Alms Light burning before the rood (or High Cross), were managed by the churchwardens, or High Wardens, as they were called. Saint Anthony’s store included pigs as well as sheep. Unmarried girls formed the Maiden store, which collected money for the lights before the Virgin, the High Cross, and Saint Sidwell. The Young Men’s store, which involved all bachelors of communicant age, raised funds to support the taper before Saint George and two lights before the High Cross. The light before the principal image of the Virgin was maintained by the store of Our Lady, whose income came from the wool from a small flock of sheep which was boarded out with individual parishioners during the year. The central funds of the parish, including the church plate, the stock, and the contents of the church house, were managed by the High Wardens, whose annual “ale,” at which people paid to drink, was the most important fund-raising event of the year. Behind them was a group of the “Four Men” or “Five Men,” senior parishioners who acted as bankers for the surpluses of all the church stores and recouped their outlay by levies on the parish.

The accounts of each store were presented by its wardens to the parish at an annual audit and copied by the vicar into his book. The Morebath “churchwardens’ accounts” are thus a compilation, recording the fortunes of all the different parochial funds or “stores.” Trychay used them as an aide-mémoire for oral presentation to the parish and as an archive for posterity. Interspersed with snatches of Latin and idiosyncratic spellings reflecting the vicar’s broad Devonshire accent, they are, at first glance, a distinctly rebarbative source. Yet out of them Duffy has, painstakingly and imaginatively, reconstructed the workings of this tiny community. He offers a marvelously elegiac portrait of the village’s collective religious life in the last decade before the Reformation, followed by a vivid narrative of the way in which that collective life was suddenly destroyed.

Advertisement

A key feature of early Tudor Morebath was the wide distribution of responsibilities. Parishioners were expected to be willing to hold office in the stores and to look after a sheep during the year. They were each assigned so many feet of the churchyard hedge to maintain; and they paid levies for the upkeep of bridges and other local amenities. Sometimes these obligations became a matter of bitter dispute: in the 1530s, there was a tremendous row because some villagers refused to contribute to the wages of the parish clerk, whose job it was to assist the priest in the liturgy and carry holy water around the parish. The recalcitrance of a few could paralyze decision-making, for the parish was governed by consensus, not a numerical majority.

As Duffy emphasizes, these ar-rangements reflected “a highly self-conscious community life, in which shared decision-making and accountability were dominant characteristics.” In any one year, twelve parishioners held parish offices, in addition to the Five Men; this in a village of only thirty-three households. The administration of the stores gave scope for a good deal of initiative, by young people as well as old, while the ales, “gatherings,” and other fund-raising events made for a full and demanding social life.

Indeed, Duffy rather underplays the purely social dimension of these activities. On my desk, as I write, lies an invitation to “a grand Jubilee Ball,” to be held in a Shropshire country house. The dress is to be in the “spirit of the Edwardian era” and there will be cocktails, supper, and old-fashioned dances. The cost of tickets is high, because the occasion is intended to raise funds to repair the fabric of St. Laurence’s, Ludlow, the local church. The invitation is a reminder that fund-raising has always been an excuse for parties and social events. The ales and gatherings of early Tudor Morebath were not just ways of maintaining lights before religious images; they were also ends in themselves, opportunities to socialize and to become intoxicated. Then as now, mild self-indulgence was legitimized by the reassurance that it was “in aid of” some good cause; participation did not necessarily prove any special interest in the cause itself.

Duffy characterizes the religious life of pre-Reformation Devonshire as

piety for practical people…for whom Christianity is about living right and dying well, but also about belonging, both to a place and to a lineage, about winning respectability, ensuring safe childbirth, about the best time to prune apples and the most effective way to ease sciatica or stop a diarrhoea.

When church benefactors paid for chantry chapels, carvings, and decorations, they were proclaiming their own social importance as much as their piety. Duffy admits that there was “just a whiff of the business logo and corporate sponsorship about it all.”

In pre-Reformation Morebath, the villagers devoted an enormous amount of labor and money to renovating and enhancing the church’s fabric, furniture, decoration, equipment, and imagery. In return, they expected prayers for themselves or their dead relatives. Although this activity was orchestrated by the vicar, the saints whose images the parishioners so sedulously maintained were, as we have seen, closely associated with their occupations and their local identity. The cult of saints was essentially a form of polytheism, though Duffy does not call it that. But it was a polytheism which expressed the values of the community. One could plausibly say, in Durkheimian fashion, that when the villagers of Morebath worshiped saints’ images, they were really worshiping themselves.

This was the active, self-regarding piety which Henry VIII’s quarrel with Rome was to destroy. First, in 1535, the people were forbidden to pray for the Pope. Then the dissolution of the smaller monasteries brought an end to nearby Barlinch Priory, whose prior had been the lord of the manor of Morebath and the patron who appointed Trychay to his benefice. Next, the Henrician government attacked the “idolatrous” worship of saints. In 1538 the lights in front of the Morebath images were extinguished and the beads, kerchiefs, and wedding rings which local women had hung about them were taken down. This was a direct reversal of all Morebath’s hectic fund-raising activity since Trychay’s arrival; and it involved the repudiation of a devotional apparatus in which villagers had invested hard-earned resources. The stores lost their rationale; and most of them disappeared in the late 1530s. All that remained were the Young Men’s store (now used for tapers before the High Cross), the High Wardens, and the Four Men.

In the later years of Henry VIII, the pressure for reform slackened. Morebath rebuilt its church house, a place for conviviality and feasting, with money and labor donated by most householders in the parish. Since 1528 the vicar had been encouraging the parish to save up for a fine set of black vestments to be used at requiem masses; and in 1547 the accumulated gifts and bequests by pious women finally reached the necessary total.

But 1547 also saw the accession of the young King Edward VI and, with it, the onset of advanced Protestantism. Within three years, Morebath parish became virtually bankrupt; the interior of its church was gutted, its ornaments defaced or confiscated, and its social institutions thrown into disarray. The new regime forbade processions, making redundant the banners and streamers in which Morebath had invested; it ordered the destruction of all “abused” images and shrines; it banned all lights and candles, save two on the high altar; it prohibited church ales; and it diverted the funds arising from fraternities and other church stocks to the repair of the church and the poor man’s box, which all churches were now required to provide. Morebath sold the church sheep, in whose maintenance most of the village had been involved, and gave up the ales, which had been the focus of social life. The Young Men’s store was wound down. The hangings, frontals, banners, basins, and candlesticks, rich in personal associations, were sold off. The vestments were distributed around the local farms for safekeeping. In an attempt to reduce the parish’s debts, the church house was let out as a private dwelling.

By the summer of 1549, the old structure of Morebath’s ritual and social life had been almost totally dismantled. When in June the Prayer Book rebels of the West Country rose in armed insurrection, demanding the return of the Mass, it was hardly surprising that Morebath should have been involved. Trychay’s accounts record a mysterious payment to five young men, who were provided with swords or a bow, “at their goyng forthe to sent denys down ys camppe.” When writing his earlier essay on Morebath, Duffy spotted that this was a misreading by the editor, Binney, of “sent davys down camppe,” that is St. David’s Down, the rebel encampment outside Exeter. On that occasion, however, Duffy assumed that Morebath had sent the men to assist the government in suppressing the rebellion. But now, with help from the Tudor scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch, he argues convincingly that it was the rebels, not the government, whom the village contingent went to join; and, since none of the five men ever appears in the records again, he concludes that they probably perished in the rebellion or its bloody aftermath.

After 1549, Morebath had no option but to conform to the new requirements of Protestant worship. The parish dutifully pulled down its rood loft, replaced its altar with a communion table, destroyed its images, bought the successive English Prayer Books, and surrendered its vestments. Then, in 1553, Edward VI’s death and the accession of his half-sister Mary put the process into reverse. The Latin Mass returned, along with the altar, and, with the help of further donations from parishioners, much of the old apparatus of Catholic worship. Some images and painted cloths were returned by villagers who had kept them in hiding. The Young Men were re-formed. Trychay triumphantly recorded that, in King Edward’s time, “the church ever decayed,” but now, under Mary, it was “comforted” and “restored.”

Mary’s death in 1558 put an end to Trychay’s rejoicing. With the accession of Elizabeth, Morebath was speedily required to dismantle its images and return to a Protestant liturgy. It did so cautiously, putting its chasuble and Mass book into safekeeping, rather than destroying them. But the rood loft came down again, the chalice was sold, and the church interior was given a recognizably Protestant character, with a communion table and a prayer desk. For all his Catholic sympathies, Trychay hung on to his post under the new regime and even acquired a second benefice nearby. Anxious to acquit him from the charge of being a mere vicar of Bray, Duffy suggests that his religion was “the religion of Morebath”: his conservatism was local and he was bound to the place, whatever change befell. Here, perhaps, Duffy protests too much. For what was the vicar of Bray’s religion if not that of limpet-like attachment to place, regardless of doctrinal requirements? “Whatsoever king shall reign/ I shall be the Vicar of Bray, sir!” But like other accommodating traditionalists, Trychay, no doubt, thought he could still serve his parishioners.

Duffy has written a powerful narrative. As a work of literature, The Voices of Morebath scores very high; and its recent award of the Hawthornden Prize for Literature was well deserved. As a contribution to history, it is also of note. The Tudor changes in doctrine and worship are familiar enough. What Duffy brings out, in a novel way, is the intense personal and communal involvement which distinguished the religion of some rural parishes in the years immediately before the Reformation.

In his earlier essay of 1995, he declared that

the reformation…meant for Morebath the permanent collapse of a parochial structure which had involved much of the adult pop-ulation in a continuous round of consultation, decision-making, fund-raising and accounting, a scale of involvement which makes the communal life of this remote moorland village look as participatory and self-conscious as the most sophisticated of European medieval cities.

Duffy, however, underrates the extent to which Protestant worship—communion in both kinds, psalm-singing, and Bible-reading—could also give scope for personal involvement and express local identity. The stripping of the altars did not make village churches any less central to rural life. What threatened the sense of community was increasing social and economic differentiation, not Protestantism. But Duffy is right to stress that, although the Elizabethan parish took on a wide range of new secular responsibilities, it was more oligarchic in structure. There were fewer local offices than had been provided by the Catholic stores and they rotated less frequently.

In The Stripping of the Altars, Duffy claimed that

the experience of Morebath almost certainly offers us a more accurate insight into what the locust years of Edward had meant to the average Englishman than the embryo godly communities which had begun to emerge in parts of Essex, Suffolk, or Kent.

This time, he is anxious not to claim that Morebath was in any sense a typical Tudor village; indeed he acknowledges that a study of the Reformation in another part of England where the Protestant gospel was eagerly embraced would look very different. He also accepts that, even in Catholic times, there were Morebath villagers who refused to hold office or contribute to the church’s funds, despite public reproaches by the priest. He concedes that there were many convinced Protestants in the West Country by 1553, and even allows the faint possibility that there may have been one or two in Morebath itself. In the fourth impression of The Voices of Morebath, he cites from the records of the church courts the revealing case of a laborer who, in 1557, when asked to pay his tithes, attacked Trychay with a sword: “a tantalising glimpse of otherwise hidden tensions.”6 But, otherwise, Duffy’s forced dependence on a single source means that he has to contemplate the Reformation through the eyes of a Catholic priest. The voices of the parishioners are silent.

The truth is that Morebath was positively untypical in its extreme traditionalism, even by the standards of the conservative South West. It was remote; it had no resident gentry and was relatively undifferentiated socially; it had the same highly traditionalist incumbent for well over fifty years; and, though religious fraternities were ubiquitous in late medieval England, Morebath was exceptional in having quite so many “stores” in relation to its tiny population. In urban parishes, the churches tended to rely on rents rather than on fund-raising by the parishioners.7

Duffy disarmingly says that he does not offer Morebath in proof of any thesis. But he certainly demonstrates that, in one Devonshire village at least, most people on the eve of the Reformation would have preferred things to stay as they were. Nowadays, we believe that the essence of modernity lies in the differentiation of social functions from one another: our concept of personal freedom presupposes that politics, work, religion, family, and friends occupy separate domains and need not overlap. But Duffy is nostalgic for the integrated little world of pre-Reformation Morebath, where there was little distinction between the community at prayer and the community as it went about its daily business. When he says that Trychay perceived the Reformation as “arrogant, destructive and un-English, a disastrous rebellion against God and the faith of our fathers,” we may guess that his own view is not very different.

The Voices of Morebath is a fine piece of microhistory, even if it is not the English Montaillou. But the microhistory of a remote country village cannot provide an adequate explanation of the wider forces of historical change. To understand the English Reformation, it is not sufficient to study those on the receiving end. We have to look at the movers and shakers: the politicians and the bishops, the evangelical preachers and the godly laymen. Eamon Duffy has no sympathy with them, but, like many Catholic historians before him, he has a deep sympathy for a vanished world.

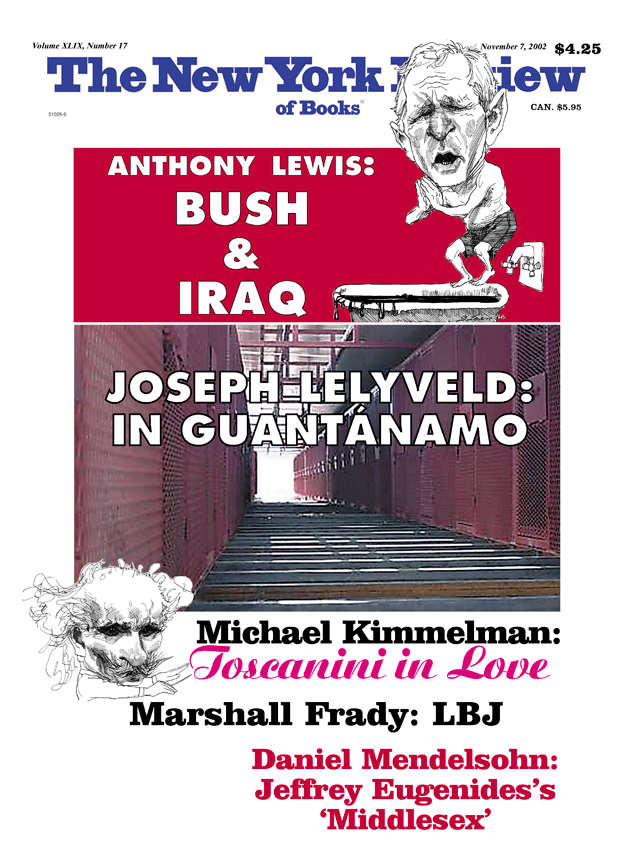

This Issue

November 7, 2002

-

1

See David Aers, “Altars of Power: Reflections on Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars,” in Literature and History (third series), Vol. 3, No. 2 (1994). ↩

-

2

Eamon Duffy, “The Reformation Revisited,” in The Tablet, Vol. 4 (March 1995), p. 280. ↩

-

3

In the late 1870s the church was restored by the prominent architect William Butterfield; Duffy remarks that “it is not clear how much the curious saddle-backed top to the tower owes to this restoration.” A few months ago, a friend of mine purchased a watercolor by the Indian administrator and amateur artist Sir James Peile (1833–1906). Entitled Morebath Twilight and dated 1868, it shows the church without the saddle-backed tower, thus confirming that it is indeed Butterfield’s addition. ↩

-

4

“Morebath 1520–1570: A Rural Parish in the Reformation” (1995), in Religion and Rebellion, edited by Judith Devlin and Ronan Fanning (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 1997), pp. 17–39. ↩

-

5

They are extensively used, for example, by Robert Whiting, The Blind Devotion of the People: Popular Religion and the English Reformation (Cambridge University Press, 1989), a valuable study of South West England. ↩

-

6

This case had already been cited by Robert Whiting, in Local Responses to the English Reformation (St. Martin’s, 1998), p. 32. ↩

-

7

See Katherine L. French, “Parochial Fund-Raising in Late Medieval Somerset,” in The Parish in English Life, 1400–1600, edited by Katherine L. French, Gary G. Gibbs, and Beat A. Kümin (Manchester University Press, 1997), p. 117. ↩