1.

Robert Bateman, a little-known disciple of Edward Burne-Jones, exhibited his full-length portrait of his wife, Caroline, at London’s Grosvenor Gallery in 1886. She is shown walking in an autumnal landscape, by implication in the park or garden of an English country house—indicated by the ornamental urn behind her and the sweeping view over the valley in the distance. Immediately striking is the almost Pre-Raphaelite obsession with minute details of dress, accessories, and landscape, all the more surprising at the height of the Aesthetic Movement in England when a generally freer handling of paint had superseded the tight linear clarity found here.

Notable too is the homage Bateman pays to the eighteenth-century Grand Manner, subtly evoked by his wife’s costume. This lovingly delineated dress of black silk or crape, trimmed at the sleeves just below the elbow with flounces of lace and worn with a wrap of antique lace, fills almost half the canvas. Whoever designed it wished to suggest the kind of garments worn by women in the paintings of Gainsborough or Reynolds, just as Renaissance artists used drapery to evoke the classical world, and rococo painters dressed their sitters in costumes based on those in Van Dyck’s portraits.

In recent years we have become much more willing to ask what the clothes worn by a sitter in a portrait tell us about his or her status, aspirations, and social milieu. As Aileen Ribeiro writes in her Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715–1789, first pub- lished in 1984 and now magnificently reprinted, “clothes played the most vital role in defining man and his part in society, to an extent that we cannot contemplate today.” When we look at pictures without analyzing the clothes the people in them are wearing, we don’t really see them.

But first, we need to know what we are looking at. Mrs. Bateman is shown in a formal dress consisting of a long black skirt worn with a bodice of the same color and material. Her ensemble is somber, but also fashionable. Under her skirt at the hips, she wears a crescent-shaped cage to hold a padded bustle, a distant echo both of the mid-Victorian crinoline and of the hooped skirts worn by women in the eighteenth century. Look closely and you see that her tight three-quarter-length sleeves are intricately embroidered with a pattern of tiny steel beads, while her chest is flattened and waist slimmed by tightly laced stays. Shell-shaped ornaments running down the front of the dress are repeated at the shoulder, bosom, and at the side of the bustle. At the back of the skirt there is a short train such English women wore in the 1750s, when the size of the hoop began to diminish and then disappeared altogether. You find velvet bands, exactly like the one she wears on her right wrist, in portraits by Reynolds and Joseph Wright of Derby.

A contemporary would have seen at once that Mrs. Bateman is in the second stage of mourning, between the full black that was customary for at least twenty-one months after the death of a close relative or spouse and the gray or lilac color permitted toward the end of a bereavement. In half mourning, a woman was allowed to alleviate the severity of black with lace and pearls. And indeed we know that Caroline Howard, a granddaughter of the fifth Earl of Carlisle, was the widow of the Rev. Charles Wilbraham when Bateman married her in 1883. Although the portrait was exhibited in 1886, the costume and the urn (a traditional symbol of mourning) suggest that Bateman began it much earlier, perhaps during their engagement.

This is why the bride wears black, but it is also why she discards the traditional widow’s cap, which, as we know from many photographs of Queen Victoria taken after the death of Prince Albert, was normally de rigueur for mourning during the whole of the Victorian period. We may even speculate that the miniature suspended from a band of old lace at her throat is a portrait of her first husband, and that the two rings conspicuous on her right hand are engagement rings. The small prayer book she carries is stamped with her new (or future) husband’s initials, RB.

At this date, it was usual to buy mourning from a London shop like Jay’s Mourning Warehouse, or from the large mourning department in Marshall and Snelgrove on Oxford Street. But it is more likely that Mrs. Bateman is wearing a dress designed by her artist husband and made by her dressmaker. Examples of the artist-designed dress are found in James McNeill Whistler’s portrait of Mrs. Leyland in the Frick Collection, inspired by Watteau’s fêtes champêtres; the uncorseted “medieval” gowns favored by William Morris’s wife Jane; or the Aesthetic outfits Oscar designed for Constance Wilde. The word contemporaries would have used to describe Mrs. Bateman’s ensemble is “artistic.” They would also have surmised that the circles in which the sitter moved were arty but not Bohemian, and not as worldly as those depicted, for example, in Tissot’s paintings of the haut monde.

Advertisement

But a sitter’s personal style has to do with more than just costume. One of the more startling features of the portrait is Mrs. Bateman’s willingness to show her prematurely white hair. In the eighteenth century, powder and wigs disguised hair color, while mature women in Gainsborough’s and Reynolds’s portraits tend to cover their hair with caps. Ingres painted the elderly Baroness de Tournon in a wig of dark brown curls. Later in the nineteenth century, women of fashion (Princess Alexandra, for example) used crude dyes to banish gray. What’s more, in the 1880s stylish women wore their hair in a fringe. Mrs. Bateman’s severe hairdo proclaims her independence from the dictates of fashion. But I wonder whether, by wearing her hair swept high up off her forehead and rolled at the back of the neck, she wished subtly to suggest the effect of a powdered wig, another touch of the dix-huitième fully in keeping with her costume.

The difficulty with trying to evaluate costume in portraits is that throughout history both men and women have seen life through the lens of art. As Anne Hollander writes, “Viewers of paintings have learned from artists how to lead richer visual lives, how to see more fully and imaginatively.” To accurately “read” a dress worn in either a subject picture or a portrait, we need to know how real clothes were cut, put together, and worn—but also when, where, and under what circumstances it was appropriate to wear them.

2.

In Fabric of Vision Anne Hollander is as concerned with the clothes, draperies, and swags of cloth depicted in religious and mythological paintings as she is with the garments living people are shown wearing in portraits. But in every case, she starts her account of a picture by asking whether the costumes depicted in it actually existed, and if so, whether they could have been worn in everyday life. No garment in a Renaissance painting, for example, is wholly fantastical. Even the biblical or legendary clothing in which Christ and his disciples are shown, invariably consisting of a full-length robe with a cloak over one shoulder, is based on male attire of the fourth century. But most modern viewers don’t realize we are looking at legendary costume in pictures by Masaccio or Rogier van der Weyden because the artists often show it alongside contemporary fifteenth-century clothing. And so, in Masaccio’s Tribute Money Christ and his apostles are in biblical dress, but the tax collector wears the short belted doublet with long sleeves common in Renaissance Florence.

Hollander further stresses the importance for Renaissance artists of the accurate rendering of richly dyed or printed textiles, of

exquisite silk fabrics and magnificent wool carpets…satin and gold-brocaded satin, velvet and cut velvet and crushed velvet, changeable silk of two colours at once, shimmering silk shot with metallic thread, stiff linen damask and floating linen gauze, thick wool felt, supple wool serge, silken veiling like mist and woollen veiling like a spider’s web.

Huge sums were spent on these wonders, so artists went to great lengths to describe their textures, colors, and folds as accurately as possible. This means that before the sixteenth century, no garment falls, is folded, clings to the body, or flies up in an irra-tional way. But even though the fabrics are real, that does not mean that a real woman would or could have worn the heavy draperies that enfold Madonnas and angels from Van Eyck to Titian.

From the sixteenth century onward artists began to use drapery in ways never dreamed of earlier in the Renaissance. In Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin in the Louvre all the participants in the drama are subsumed under the colossal swag of crimson drapery that flows, impossibly, across the top of the picture. Hollander concludes that by using fabric to replace the heavenly apparition of God and angels usually found in depictions of the death of the Virgin, “Caravaggio proves that painted draped folds could have their own power to infuse an image with holiness, or any other spiritual or emotional suggestion.” The substitution of drapery for a vision of heaven at the death of the Virgin emphasizes the doctrine of her mortality, but leaves open to question her bodily assumption into heaven, an ancient tradition that was not then a doctrine of the Church.

Even when costume or drapery has no such iconographic function, the subtle distinctions Hollander makes about superficially similar articles of clothing help us to see a picture as the artist meant us to see it. In the eighteenth century the Venetian Giovanni Battista Tiepolo painted the legendary hero Antony in Roman armor, short skirt, and sandals, while his Cleopatra wears sixteenth-century costume such as you find in the paintings of Veronese. But these garments are not historically accurate copies of real clothes. They are theatrical costumes of the kind worn in pageants, parades, or on the stage. Moreover, Tiepolo is not copying garments his viewers would have recognized from a specific theatrical performance. In exaggerating the height of a collar, the width of a sleeve, or the curve of a hairstyle, he was simply giving his pictures a quality of staginess, a dressed-up look that Hollander calls “quasi-theatrical”—and that (I found myself thinking) gives Tiepolo’s pictures an unexpected affinity with Walt Disney. But if Tiepolo’s characters wear fancy dress, it is “real” fancy dress, for we can see how the costumes in his pictures are cut, lined, sewn together, fastened, and seamed. This implies—although Hollander doesn’t say so—that the artist maintained a well-stocked dressing-up cupboard in the studio.

Advertisement

Fancy dress was introduced into France and England at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In Hollander’s book it can be seen in the costumes in which Gainsborough painted his sitters, or in Watteau’s evocation of figures from the commedia del-l’arte. Naturally men and women continued to wear ordinary clothing for portraits, but the popularity of fancy dress meant that increasingly clients wished to be depicted as the goddess Diana, a pilgrim, a shepherdess, or—in the case of Louis XV—cunningly disguised as a clipped yew tree. But the difference between everyday dress and fancy dress isn’t always easy to spot. When you next look at the strangely dressed people in a canvas by Canaletto, for example, bear in mind that Venetian patricians wore gowns with voluminous sleeves of black, scarlet, or violet according to their rank and employment, and that men and women wore masks and dominoes throughout the year, not just at carnival time. On the other hand, Goya’s famous clothed maja is blatantly an aristocrat dressed for a masquerade in the tight-fitting jacket worn by lower-class Spaniards, including Beaumarchais’s Figaro.

The whole subject of fancy dress in art is unexpectedly nuanced. What came to be called Vandyke costume, for example, is a fiction based upon a fiction, because Van Dyck himself invented the dresses women wear in his portraits in order to give them a décolletage no respectable English lady would have contemplated in the seventeenth century. In Watteau’s Le Repos gracieux of about 1713, included in Hollander’s account, a man in Vandyke dress, with a buttoned-up doublet and ruff, courts a lady costumed for a masked ball, but it is impossible to say for certain whether he is an actor from the commedia dell’arte (in which case, his inamorata might be an actress), an actor addressing a lady of fashion, or simply another guest in disguise.

Fabric of Vision is published to coincide with an exhibition of the same title that closed at the National Gallery in London on September 8. Though I learned a lot from the book, the show was a different story. Pictures were borrowed not for their aesthetic quality, but because they illustrated a point Hollander wanted to make. And since so many of the most original things she has to say are about paintings that could not conceivably have been lent to an exhibition, the book is much more stimulating than the show. Both book and show cover the twentieth century, including Surrealism and Cubism, but these sections are comparatively unenlightening since we know a lot about how suits and dresses from the 1920s onward were made and worn. Finally, the author writes with such conviction and range of historical reference that I was willing to take her sweeping generalizations on trust, but there isn’t a single footnote in a long text to back her up.

3.

Just as French was the lingua franca of the eighteenth century, Paris led the world in fashion. But in Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715–1789 Aileen Ribeiro isn’t interested only in French haute couture or even in the upper echelons of society. She tells us exactly what men, women, and children of all classes put on and took off at all times of the day and night from St. Petersburg to Madrid, and from Warsaw to London. No item of clothing is uninteresting to her. She works her way through a gentleman’s wardrobe from the nightgown, dressing gown, and slippers he wore for his morning levee to the shirts, breeches, neckwear, wig, hat, gloves, cane, and sword he might wear in town, not forgetting the greatcoat for out-of-doors, and the formal attire for court and evening.

Since most of the clothes no longer exist, she uses paintings and prints to bring them to life. But she also draws on written sources, both nonfiction and fiction. The eyewitness descriptions she cites are often highly detailed, as when the diarist Mrs. Delany saw the Prince of Wales wearing a coat of “mouse-colour velvet turned up with scarlet and very richly trimmed with silver” or noted King George II’s three-cornered hat “buttoned up with prodigious fine diamonds” that matched the diamond buttons on his blue velvet suit. Imaginary clothes sound just as ravishing. Samuel Richardson describes his heroine Clarissa Harlowe in a yellow silk dress embroidered “in a running pattern of violets and their leaves; the light in the flowers silver; gold in the leaves.” Ribeiro’s own descriptions are wonderfully vivid. It is certainly interesting to learn that the Empress Maria Theresa organized sleighing parties in winter where the ladies were dressed in fur-trimmed velvets covered in diamonds. But when Ribeiro adds that they “rode on gilded sledges shaped like swans, horses, griffins or unicorns” the scene rises up in front of our eyes.

By the time we are halfway through her book, we find ourselves mentally dressing and undressing figures in the paintings she illustrates, trying to understand exactly how a stiff court dress was constructed, how a woman got into it and held it up, and imagining how she walked, curtsied, or sat down once it was on. For the texture and weight of materials, combined with the rigid etiquette expected at court, affected the way men and women moved. When Peter the Great visited Berlin in 1717, the Tsarina wore so many orders, relics, and portraits of saints fastened to her gown that when she walked one alarmed hostess noted that “the jumbling of all these orders…made a tinkling noise like a mule in harness.” But then Russia at this period must have been a very odd place. In her discussion of the history of rouge, Ribeiro notes that the fiery spots of crimson on the cheeks of Russian women formed a startling contrast to their teeth, which were dyed black, then polished until they gleamed like lacquer.

Even in Paris, fashion could be a cruel mistress. When in the 1720s women sat down in their vast circular hooped skirts, their legs stuck straight out, like wooden dolls. To be presented at the French court, a woman was required to wear the “grand habit” consisting of a heavily boned bodice and train, all made of the same weighty fabric, with elaborately flounced lace sleeves:

The lady had to curtsy with a large hoop to kiss the hem of the queen’s gown (having taken off her glove to do so); after a brief conversation, she then retired backwards, with three curtsies, having to cope not only with the huge hoop but also with the enormous train.

The Marquise de La Tour du Pin, who was presented at court in 1787, complained that the boned bodice cut into her shoulders, and that

the weight of the dress made it impossible to raise the foot in heels three inches high, so the correct movement was to take little gliding steps, the lady with a huge hoop looking like a ship in full sail.

Not surprisingly, the services of a dancing master were required to teach young women how to perform these maneuvers without falling flat on their faces.

The garment described above is the mantua, a fashion of the seventeenth century that continued to be worn on special occasions at court throughout the eighteenth century. For less formal wear it was largely superseded by the sack dress in the 1720s. This looser, more comfortable garment evolved from the dressing gown and fell in loose pleats at the front and back. Ribeiro, like Hollander, describes the gradual simplification and freeing up of clothing in the later half of the eighteenth century, largely as a result of the importance of English sporting and country attire as an inspiration for high fashion.

It is a pleasure to follow Ribeiro as she traces the evolution of an article of clothing, whether she is contrasting the simple stiff waistcoat men wore at the beginning of the century to the full- blown rococo splendor of the same garment “decorated with fringes of silk, silver and gold thread” or explaining how men’s wigs evolved from the heavy, full-bottomed type to the lighter bag wig, tied at the back with a black silk ribbon, which replaced them.

After reading this book, most of us will be able to guess the date of a picture based on the shape of a dress, the height of a wig, or the design of the material. The hoop, for example, changes in the mid-1720s from a birdcage to an oval shape, and by the 1730s had flattened in front and increased in width to as much as eleven feet in circumference, which meant that women could only enter a room by walking sideways through the door. This is the style we see in J.-F. de Troy’s ravishing painting La Déclaration d’Amour of 1731, where the lady with her back turned to us conspicuously displays a sack dress made of black silk material printed with a large rose and silver floral pattern of the kind that had only just come into vogue. The shapes of the dresses and the sumptuous materials from which they are made situate the participants in the scene at the epicenter of fashion as surely as the scarlet heel on the young man’s shoe tells the viewer that he has been presented at court.

Contemporary viewers would not have cared who actually made the dress, for tailors and seamstresses had little status. But they would have known without having to think about it that the hugely expensive floral silk had been woven in Lyons, and that the owner of the dress bought the fabric at a mercer (the middleman between the silk weaver and his customer), probably in one of the ultrafashionable shops in the Palais Royale. The gown would then have been fitted by a couturier and trimmed by a marchande de modes or modiste—whose services became all-important later in the century as rococo taste saw dresses covered in ribbons and furbelows.

Even the most privileged women were aware of how difficult it was to keep such a dress clean in an age when bathing was rare, the washing of hair considered dangerous for the health, and when perspiration, mud from the streets, and powder from wigs stained unwashable silks. Ribeiro cites the wider availability of cheap printed and plain materials that could easily be washed as one of the positive effects of the Industrial Revolution. Every page of Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe is crammed full of such fascinating information, all backed up by footnotes that can be almost as interesting as the text. Finishing it, I had the satisfying sense that Ribeiro hadn’t told us half of what she knows. Though the text is substantially the same as that in the 1984 edition, Yale University Press has given the book a new format and design, and added to and updated the illustrations. What a gift.

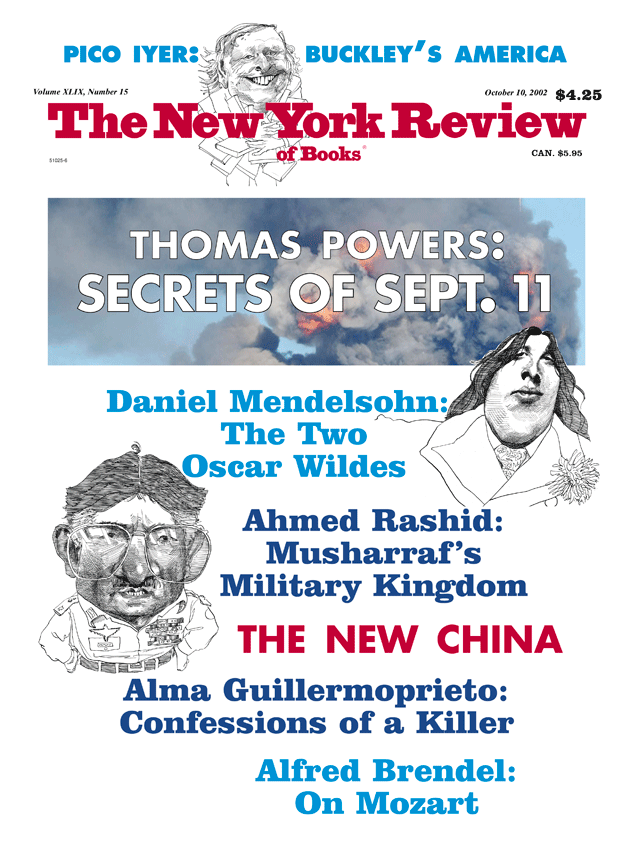

This Issue

October 10, 2002