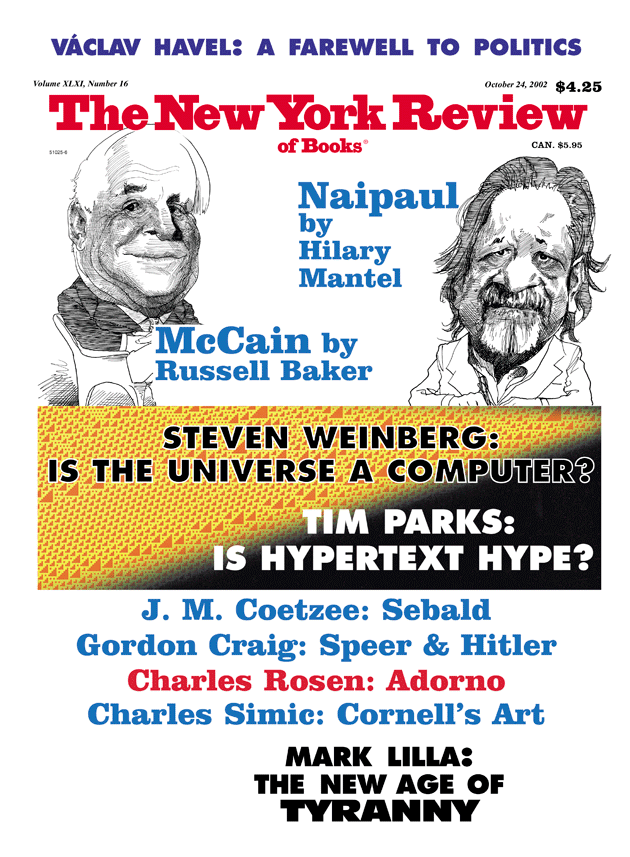

John McCain’s first hero was Robert Jordan, the hero of Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Hemingway’s novel ends with Jordan dying in a struggle for what he believes to be a good cause. The pages of McCain’s Worth the Fighting For (written with the help of Mark Salter) are strewn with tributes to his several heroes, and they are an odd collection for a politician. With the exception of Ted Williams, they are all fighters for political causes, and most lose in the end.

This roll call of heroic losers may explain why McCain is one of the few politicians still alive who can stir some enthusiasm in our half-dead electorate. To lose a fight for a good cause confers an aura of gallantry on the loser, and gallantry attracts a public. McCain seems instinctively drawn to the gallant act. He is a romantic in a line of work now viewed by much of the public as a shabby conspiracy among money hustlers.

This may explain too why many of his colleagues dislike him. Because money has become the mother’s milk of American politics, politicians spend much of their time trying to cadge campaign contributions from the rich. Waving the tin cup is hard on anyone’s self-esteem; for a congressman the mortification must be doubly painful when a McCain is winning Boy Scout points by preaching that politicians are corrupted by being on the take.

But what alternative is there for the man who yearns to do the state some service? To win election, candidates now need what Senator Everett Dirksen used to call “real money.” (“A million here, a million there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”) The New York Times estimated that the amount spent in the 2000 elections was $3 billion. Joseph Napolitan, a political consultant, told the Times: “I don’t understand why someone would spend $2 million to get elected to a $125,000-a-year job. But they do it all the time.”

Money’s commanding role in politics has provided McCain with his most famous cause: reforming a campaign finance system that nobody likes and almost no politician can live without. It was the fight for reform that lifted him above the mediocrity of the Senate and gave him enough public stature to make an effective run at the last Republican presidential nomination.

For years Washington professionals, echoed by their media chorus, had insisted that campaign finance reform was not an issue the public cared about. This made it McCain’s kind of issue: hopeless and worth fighting for. He made himself an amusing, then insistent, then boring nuisance to fellow Republicans, who were committed to the curious proposition that their party was singularly dependent for existence on handouts from the treasuries of Croesus.

As Bill Clinton’s gaudy fund-raising excesses suggested, Democrats were as reliant as Republicans on rich customers shopping for compliant statesmen. (“Gaining access” was the euphemism. Big spenders weren’t actually buying congressmen, senators, and presidents, everyone said—they were only buying “access.” Which meant that living, breathing congressmen, senators, and presidents answered their phone calls, instead of machines that say you can leave a message after the beep.) Because Republicans objected so stridently about McCain’s reform proposals, Democrats—the fakers!—were able to pretend they were just as pure as McCain was.

In any case the matter developed as a fight among Republicans: the party faithful, old guard, establishment, call it what you like, versus the reformer. Republicans hate reform. They have always hated reform. They hated it when Theodore Roosevelt tried to force it on them a hundred years ago. They hated it when Eisenhower and the internationalists from the east succeeded in forcing it on them in the 1950s. They have hated the northeastern internationalists ever since, have gradually purged the party of them, and reconstituted it as a party of Southerners, evangelical Christians, and small-town prairie folk. Now here was this nuisance McCain. They’d thought they were getting a hero: all that agony through all those years in the Hanoi Hilton. And now—some hero! Just another damned reformer.

They roughed him up a bit when he insolently pushed for congressional action on his campaign reform nonsense, but he seemed to be a slow learner. He decided to run for the party’s presidential nomination, though the nominee had already been chosen by people immune to the reforming impulse—the establishment, old guard, call them what you like—the kind of men who assemble money, governors, and similar necessities with a lot of telephone calls, then lay out the plan in a conference call.

They represented the concentrated wealth of the Republican Party, and their man was George W. Bush. Republicans experienced in such things were awed by the Texas-size bundle they put behind him: the biggest assemblage of money ever gathered for the purpose of obtaining a mere presidential nomination.

Advertisement

McCain decided he would make a run at the nomination anyhow. He had always wanted to be president, not that he had some great program to achieve, he says, but the ambition was on him, and he believed his military and political experience made him more qualified than any of the other men running. He would talk about campaign finance reform, but it would be just one element of his overall attack.

That campaign was a model of gallant battle, if only because McCain was so obviously doomed from the start. Hopelessly underfinanced, he chartered a bus, invited the news people to climb aboard, and went to New Hampshire to fight against the concentrated wealth of his own party. It was a chapter out of Don Quixote, made all the more comical when the New Hampshire voting, and later Michigan’s, showed that McCain would make a formidable vote-getter indeed. More formidable by far than Bush, a man glaringly deficient in the crowd-pleasing arts.

The party’s concentrated-wealth wing, anything but thrilled by McCain’s way with the masses, could only instruct him in the authority of real money; they simply buried him under mountains of it in states where the making of the people’s choice was confined to officially certified Republicans. So much for a McCain presidency. His power to charm Democrats and independents cut no ice with men who had the White House in mind and the wherewithal necessary for gaining access to it. To update the wisdom of Damon Runyon, the race is not always to the swift, or the battle to the strong, or the election to the candidate rolling in money, but that’s the way to bet it.

Time’s passage has not diminished McCain’s bitterness about the brutality of Pat Robertson’s Christian right in the South Carolina primary. He says Robertson “contacted thousands of evangelical households to warn them not to vote for me and allege that my friend, Warren Rudman, who is Jewish, was bigoted against Christian voters.”

The attack of the political parsons was just part of the Bush group’s assault. Direct mail and attack ads came from the gun lobby, the anti-abortion lobby, and various other Bush money outlets masquerading under names like “Americans for Tax Reform” and “National Smokers Alliance.” Bush’s surrogate spenders, McCain says, ran six times as many ads as he did in South Carolina:

You couldn’t turn on a television or radio without hearing an attack on me every few minutes…. In e-mails, faxes, flyers, postcards, telephone calls, and talk radio, groups and individuals circulated all kinds of wild rumors about me, from the old Manchurian Candidate allegation to charges of having sired children with prostitutes.

A Republican conservative speaking unkindly of the Christian right is, like a Democratic liberal denouncing organized labor, the rarest kind of political bird. The Christian right is now so vital to Republican success that party leaders call it one of their “core” constituencies; i.e., a voting bloc that must in no circumstance be offended. Yet McCain, while insisting that he is still a conservative, goes at the evangelicals with something close to savagery.

Consider him on Paul Weyrich, a noisy gadfly of the politico-Christian world, or, in McCain’s words, “an often intemperate and pompous defender of the faith.” In a long-ago committee hearing Weyrich once patronized McCain with a display of such superior piety that McCain is still fuming:

Weyrich possesses the attributes of a Dickensian villain. Corpulent and dyspeptic, his mouth set in a perpetual sneer as if life in general were an unpleasant experience, he is the embodiment of the caricature often used to unfairly malign all religious conservatives. He is the joyless preacher who for the sake of God and country sorrowfully consents to participate in the profane business of politics….

His summation: “a pompous, self-serving son of a bitch.”

Here McCain is recalling Weyrich’s testimony against the first President Bush’s appointment of John Tower to be secretary of defense. Tower had been attacked as a heavy drinker and “womanizer.” McCain concludes with a reflection of his own on the nature of God:

…Weyrich fairly trembled for his country as he considered God was just and not likely to let pass unnoticed the presence of a boozy reprobate in the highest councils of our government. I don’t know why not. God has seemed to suffer more than a few such scoundrels lowering the moral standards of public office since the very first days of the Republic’s founding, and still He continues to bless our country with His bounty.

McCain has clearly advanced to a new stage of his career. Now he no longer feels compelled to be discreet about his discontents with conservative domination of his party. Personal dislikes and policy disagreements with party leaders are voiced in remark-ably plain speech. If his first memoir, Faith of My Fathers, was a campaign biography, this one is a book of self-discovery. Here McCain declares independence from the encrusted dogmas of conservatism.

Advertisement

He keeps saying that he remains a conservative, but this book does nothing to confirm it. It is the work of someone who has found out, rather late in life, who he is and what he truly believes. Self-discovery seems to give him the nerve to speak his mind with a candor rare among politicians. The result is a book packed with extraordinary indiscretions for a still-practicing politician.

He speaks critically of the Republican Senate leaders, Trent Lott and Don Nickles. He insults retiring Senator Phil Gramm of Texas, saying he abandoned a principled stand on foreign policy to gain a few votes in a 1996 presidential primary. With apparent pleasure he recalls telling a fellow Republican, Senator Exon of Nebraska, “You’re a goddamn liar.” During the same onset of high temper, he had to restrain himself from publicly denouncing another, Senator Shelby of Alabama, for “bad faith.”

He criticizes conservative Republicans for pursuing isolationism in foreign policy. He criticizes Newt Gingrich’s resort to “scorched earth tactics” that broke Democratic control of the House of Representatives and led to years of partisan bitterness. He accuses conservatives of letting “healthy skepticism about government sink into something unhealthy, an embittered loathing of the federal government.”

To all this add his triumph in winning passage of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance bill, which among other things bans soft money, curtails the use of phony “issue ads,” and requires more disclosure. The Republican leadership hated it, the President hated it, and many Democrats hated it equally but had trapped themselves politically and had to vote for it.

McCain-Feingold is an astonishing accomplishment. Cynicism about campaign finance is now such that it is widely assumed that finaglers will soon find ways to get around the new law and keep the money spigots legally gushing. In getting the bill enacted, however, McCain beat Washington’s most formidable political powers. In doing so he proved they had been wrong for years in telling themselves the public didn’t care about big money being corruptive of politics. His failed presidential campaign disclosed a public appetite for campaign reform that startled old-line politicians and contributed, perhaps decisively, to the passage of McCain-Feingold.

Elizabeth Drew’s Citizen McCain is especially interesting on McCain’s change of political personality. Drew is like a good combat correspondent covering Washington as a battlefield. She works close to the front lines and specializes in detailed reports of each person’s actions. No Washington reporter can beat her for knowing precisely what happened, how, and why. Her look at McCain focuses on his doings during the fight to pass the campaign finance bill, but she has a shrewd eye for political trends too, and she thinks McCain has moved out of conservatism’s house for good reason.

No matter how insistently he claims brotherhood with the right, McCain has become a man of the center, according to Drew. The party that holds the center has historically dominated American politics, and McCain gradually saw that the center was unoccupied, and there for the taking. Bush and Gore had both failed to seize it, and both had lost the 2000 presidential election. McCain saw a vacuum, Drew writes, “a place for the growing number of people who don’t identify with either party, or with conventional politics.” It could have been filled by “a more stable Ross Perot, a Jesse Ventura without the feather boa,” a Colin Powell willing to run for president as a third-party candidate.

Now Bush has expanded the vacuum by “governing from the right,” Drew says. By the summer of 2001 McCain had moved steadily toward the center by supporting regulation of HMOs through a patient’s bill of rights, by opposing aspects of Bush’s tax bill that especially benefited the rich, by joining Democratic senators on bills to tighten checks on gun purchasers at gun shows and make generic drugs more widely available to consumers.

Even in foreign policy McCain’s position has been distinctively his own, as, for example, in the present debate about a preemptive war against Iraq. He supports it and believes it would “not be very difficult” to win, but calls for a policy change unlikely to amuse Bush’s Defense Department strategists. In a recent essay in Time, he advocates efforts to create democratic governments not only in Afghanistan and Iraq, but also in various tyrannies allied to the United States:

Change must also come to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, Iran, the Palestinian Authority, and wherever nations are ordered to exalt the few at the expense of the many.

Shades of Woodrow Wilson! The conservative policy on dictatorial regimes was articulated a generation ago by Jeane Kirkpatrick. It holds that some dictatorships are more civilized than others and may be distinguished from bad ones by the degree of their willingness to behave agreeably on matters important to Washington. Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan are classic examples. McCain’s lumping them with Iran, which is part of Bush’s “axis of evil,” is an extraordinary departure from the accepted order.

Drew sees McCain as an instinctively gifted politician who knows he is “a magnet for those tired of political double-talk [and] of trimmers,” and he “acts accordingly—mostly out of instinct,” she writes. “It would be folly for anyone else to try to mold himself into a ‘John McCain.’ His authenticity is a large part of his appeal.”

This naturally leads to speculation about his becoming a third-party candidate. Though he insisted to Drew that he was not interested, he “never completely slammed the door shut,” she says. There is an inviting parallel with the story of Theodore Roosevelt, who ran as a third-party candidate in 1912. There are also some differences, and age is one. Roosevelt was only fifty-four years old when he ran in 1912. McCain will be sixty-eight when the next election is run. Ronald Reagan of course was sixty-nine when first elected, and old age has never stopped the presidential itch. As Vermont’s late Senator George Aiken once observed, “The only cure for that disease is embalming fluid.”

With the third-party question in mind, it is entertaining to read Worth the Fighting For as though McCain had originally meant to title it “The Making of a Centrist.” What does he want to tell us about the elements of his character that account for his “authenticity”?

Well, for one thing, he turns out to be fond of boasting about his defects, as an exceedingly honest man might insist that his portrait reveal warts and all, but especially warts. These defects often turn out to be the sort that have a politically appealing regular-guy charm.

“I’m a wise ass,” he tells us. The flaw has “gotten me into more trouble in my life than I deserved to get out of.” Why this weakness?

I like to laugh, and I like to make people laugh. Solemnity isn’t my natural condition, and I’m glad it isn’t. But occasionally my sense of humor is ill considered or ill timed…. More than once, I’ve made some crack that had been better left unuttered….

Some think “I style myself a reformer to gain favorable press interest” and “some think I do it simply because I enjoy being a pain in the ass,” he states, then confesses there is “an element of truth in each charge.”

Like many an ordinary Joe, he has a dangerously short temper which has led to embarrassing incidents. Once it embroiled him in a cursing, shoving match with a Democratic congressman inside the Capitol and McCain “suggested we take it outside to settle it.” Somebody had been bad-mouthing the Republican House leader. McCain took exception. Marty Russo of Illinois took exception to McCain’s exception. Coarse language and shoving ensued. They didn’t take it outside. Both have been “quite friendly” ever since.

Another time it was the press that lit his fuse with persistent questioning about whether he was involved in possibly unethical conduct. Two especially vigorous reporters set him off:

…I called them idiots and worse. I shouted at them, cursed them, and eventually slammed the phone down on them. It was ridiculously immature behavior, which, although I have been irritable with reporters on occasion, I never repeated.

Well, who wouldn’t like to slam a phone down now and then on those reporters we see hounding troubled people on TV with rude questions? And while dignity may be affronted when one congressman invites another to step outside, is it not what a manly man would naturally do when he hears his leader’s good name traduced? In any event, both outbursts were valuable learning experiences for which McCain is now, he tells us, a wiser and calmer spirit.

In a highly detailed account of “the Keating five” scandal of the 1980s, he says his own stupidity led him to become a special pleader for a corrupt savings-and-loan company run by a big campaign contributor, Charles Keating. Four other senators, all Democrats, also intervened with bureaucrats who were troubling Keating (thus, “the Keating five”). McCain says Keating wanted them “to get federal regulators off his back.” He says inexperience and ignorance of the political game—which is to say, the innocence of the political greenhorn—led him to commit improprieties, which a Senate inquiry later forgave.

One accepts this self-portrait of the good man gone wrong through too much innocence, for there is simply nothing in McCain’s history before or since to suggest a man who would sell his office for a campaign contribution. The considerable space devoted to his story here suggests he is still afraid the scandal hurt his reputation. It was probably this early brush with disaster that concentrated his mind on the evils of campaign finance.

Besides this recital of defects he is outspoken about his own ambition. Politicians are expected to have ambition. Dynamic political writers say it takes “fire in the belly” to win the presidency. But talking about one’s ambition is considered bad form and worse politics, like admitting that you have been seeing a psychiatrist. McCain doesn’t simply talk about it; he talks in the tone of a sinner making confession:

I have craved distinction in my life. I have wanted renown and influence for their own sake. That is, of course, the great temptation of public life. Few are immune to its appeal. The desire to be somebody has driven many a political career much further than the intention to do something. I have never been able to conquer it permanently….

And later, writing about his presidential campaign:

I didn’t decide to run for president to start a national crusade for the political reforms I believed in or to run a campaign as if it were some grand act of patriotism. In truth, I wanted to be president because it had become my ambition to be president.

He doesn’t fail, however, to say he thought his military and political experience also made him the best qualified man in the field.

All this fills out the portrait of McCain as an outsider struggling against the superior forces that run the insider’s world. With his all-too-human handicaps he nevertheless fights the insiders’ system, which is dependent on corrupt finance, and he angers the system’s bosses by saying the word out loud. Corrupt! In a party that has historically represented the money interest in American life, he tries to defeat the money interest’s candidate for president by waging a populist campaign. Such criticism inevitably makes enemies, especially in a party whose members are exceedingly fond of their enmities. “I have gone from a nuisance to an enemy as reviled as any Democratic opponent,” he acknowledges. Or is it a boast?

Well, the hostility is mutual: “I don’t admire some of our leaders any more than they admire me. Neither am I thrilled with the direction they have given our party in recent years, or with their style of partisanship that considers political opponents as inferior moral characters.”

Modern culture encourages every man to be his own hero, every woman her own heroine, so it is unsettling to find Senator McCain sprinkling his book with tributes to the men he admires more than himself. As cited above, Hemingway’s fictional Robert Jordan, who dies in the end, is Hero Number One, having been discovered by chance when McCain was twelve years old. Randomly choosing a book in which to press a four-leaf clover, he started reading a patch of Hemingway dialogue—“What are you going to do with us?” “Shoot thee.” “When?” “Now.”—and couldn’t stop reading. Jordan is the hero McCain now uses to open his own book.

People familiar with recent history may be astonished. Jordan is an American fighting on the Communist side in the Spanish Civil War. Through much of the twentieth century, he would have been denounced as “a dupe of communism” and roughly handled by congressional stalwarts against Red subversion. No sane politician would have dared praise him. Here is cause for melancholy reflection among Republicans: anticommunism, the cement that once held the party so tightly together, has become such a dead letter that a Republican politician can now lionize a fellow traveler.

What McCain wants Jordan to tell us about himself is obvious enough. Jordan, he says, was “brave, dedicated, capable, selfless…a man who would risk his life but never his honor.” Facing death, his final thoughts provide McCain’s book title: “The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.”

And what about Emiliano Zapata? A Mexican revolutionary in 1910, he was the subject of the Marlon Brando film, Viva Zapata! McCain was in high school when he saw it, and it remains his favorite movie. Again there is a political figure fighting for a good cause, and again he will lose. Still, the movie “enlivened my dreams of fighting for justice as fearlessly as Zapata had.”

Four other political heroes are more conventional: there is Theodore Roosevelt, of course. (“…My God, what a superior man TR was.”) There are two recently deceased Democrats whom McCain knew well—Representative Morris Udall of Arizona and Senator Henry (“Scoop”) Jackson of Washington—and the late Republican Senator John Tower of Texas. Udall, though a man of irresistible charm and sweetness of character, was a liberal, an environmentalist, and an opponent of the Vietnam War, which is to say, thoroughly un-Republican. “Scoop” Jackson was a Democratic regular from the original Kennedy mold: cold warrior, loyal party workhorse, hawkish on Vietnam.

Like most McCain heroes, Udall and Jackson were both losers. Each had once run for the Democratic presidential nomination; both were defeated. When John Tower suffered his defeat he was already an ex-senator. President Bush the Elder chose him for secretary of defense, and what happened then was a wondrous tale of private score-settlers taking charge of public policy. McCain gives a long account of that bizarre incident in which personal animosities led to Senate rejection of the Tower nomination.

It is an absorbing tale of rancor creating havoc among the normally clubby gentlemen and ladies of the Senate. McCain is still puzzled about why Tower’s former colleagues rejected him. Why he elevates his good friend Tower to hero’s stature is not clear either: maybe because it was his first experience of fighting in support of a man he believed worth fighting for, and losing.

Finally there is Ted Williams. It’s clear why McCain chooses him. Like McCain, Williams was trained as a Navy pilot; he saw combat in the Pacific in World War II, and interrupted a famous baseball career a second time to return to combat in the Korean War. What’s more, “No one was ever more determined to be his own man than Ted Williams.”

In conversation with the aging Williams, who needed a walker to get around, they discussed a crash landing in Korea. Williams’s plane was on fire, hydraulics shot, landing gear locked in the up position. He should have ejected, but instead made a wheels-up landing. Why didn’t he eject?

“He was six feet four,” McCain writes, “and he’d looked up at the canopy and at the instrument panel and known he would break both his knees. ‘I’d have rather died,’ he said, ‘than never to have been able to play baseball again.'”

When McCain ran for president in New Hampshire, Ted Williams came up from Florida and endorsed George Bush. That “stung me a little,” McCain concedes, but “I shook it off.”

This Issue

October 24, 2002