1.

J.M.W. Turner was born in London in 1775, the only son of a Covent Garden barber and a mother so unstable that she was to die in a lunatic asylum unvisited and unmourned by her husband and child. A prodigy, Turner first trained as an architectural draftsman before the Royal Academy schools accepted him as a student at the age of fourteen. Although he had little formal education and may have suffered from some form of dyslexia, these very disadvantages, coupled with a powerful intellect and raging curiosity, turned him into a voracious autodidact. At the Academy, he was instructed in the rudiments of his art through the academic practice of drawing first from antique casts, and then from life. The president of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds, taught his students to differentiate between the hierarchies in art, from history painting, the most prestigious, on down to landscape, portraiture, and lowly genre scenes. The importance of these teachings for Turner’s later artistic development can hardly be overstated. As a landscape painter, Turner absorbed the idea that a great artist idealizes nature, transcending the particular to express a general truth. For Sir Joshua, the purpose of a great work of art was to appeal to the imagination and not simply to the eye. Turner learned to look at art through the lens of old masters such as Claude, Poussin, and Gaspard Dughet.

But there is another side to Turner’s art. As a boy and as a young man he roamed the streets of London, visiting the panoramas and dioramas that were then a feature of late-eighteenth-century popular entertainment. Influenced by such spectacles, the seventeen-year-old used his art the way a journalist uses his pen, to report on current events. This happens as early as his watercolor study The Pantheon, the morning After the fire, an “eyewitness account” of the destruction of a famous London theater in January 1792. Though a finished work of art and exhibited at the Royal Academy in that year, it is so immediate and realistic that Turner even shows the icicles formed where water from the firemen’s hoses dripped off the building. Side by side with natural spectacles such as avalanches and storms at sea, Turner never lost his interest in recording dramatic current events, whether he worked from newspaper accounts, as in his Battle of Trafalgar of 1806, or was actually present as history was being made, as in his two oil paintings Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, exhibited in 1835 (see illustration on page 22).

Turner spent a lifetime filling his notebooks with quick sketches, some of which he turned into finished watercolors back in his studio. This working method enabled him to add or eliminate details, and so to transform the raw data gathered on these sketching expeditions into highly wrought works of art expressing his thoughts on nature, history, politics, and society. When it comes to finished works as opposed to sketches, we can rarely assume that a scene we are looking at is an accurate description of what Turner saw in front of him—for he omitted, distorted, and added details for his own artistic purposes.

Many of the finished watercolors, and particularly those that Turner exhibited at the Royal Academy, are rich in symbolic or associative content. Others, equally finished, are straightforward topographical views. A vast number of sketches and watercolors that were unsold during his lifetime and found in his studio after his death are primarily simple descriptions of what he saw in front of him and recorded in his ever-ready notebooks. To distinguish between the intended function of each of these works of art is fundamental to understanding Turner’s genius, and it is here that we begin our attempt to interpret any work by him.

Turner reached his maturity in the years when the war with France made travel on the Continent virtually impossible for British citizens. As we learn from James Hamilton’s Turner’s Britain—the catalog for an exhibition at the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery in Birmingham, England—for twenty-eight years, between 1790 and 1819, he traveled up and down the British Isles to find his subjects, crossing the Channel only once—and then only for a few months—during the summer of 1802 when the Peace of Amiens enabled him to visit Switzerland, Savoy, and France. During his long period of domestic touring, Turner came to know a British countryside under constant threat of foreign invasion. The medieval cathedrals at Salisbury and Canterbury, a country fair in Wolverhampton, a distant view of Harewood House: such watercolors are accurately descriptive but they are also images of peace, continuity, and stability at a time when news from France was of insurrection, regicide, and military conquest.

Why do we sense that such landscape and architectural studies are embedded with meaning, in a way that those of the architect and topographical artist Paul Sandby (1721–1798), for instance, are not? The answer has to do with the connections Turner makes between landscape, architecture, and historical memory. More than any of his predecessors or contemporaries, Turner weaves into his imagery a sense of the past impinging on the present. This is where a close analysis of Turner’s working method is particularly revealing. In the preliminary sketch for an early watercolor view of the romantic ruins of Ewenny Priory in Glamorganshire, for example, sunlight pours through empty Gothic windows onto the effigy of a recumbent knight. In the finished watercolor, however, Turner has added details that are not present in the sketch: chickens and pigs overrun the dirt floor, which is now littered with farm implements. By comparing the sketch with the completed watercolor, we may presume that Turner embellished reality. If so, his purpose was to turn a merely picturesque view into a commentary on British history, a sort of vanitas or meditation on the Reformation’s wanton destruction of a once powerful Benedictine priory.1

Advertisement

But we have to be careful in our readings of such images, for it is always possible that we are putting meanings into them that Turner never intended. He himself said of the young John Ruskin that the critic “sees more in my pictures than I ever painted.” And yet the large oils exhibited at the height of the Napoleonic Wars undoubtedly reflect Turner’s awareness that he was living at a time when England’s fate hung on the outcome of battles and revolutions, and on the personalities of a few men like Wellington and Na-poleon. This is how to see Snow Storm: Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps of 1812, an oil painting that announced a whole new genre of cataclysmic history painting in England, later to be exploited by John Martin and Francis Danby. The picture’s remarkable composition consists simply of vast arcs of dark and light tone that draw the eye into a vortex of snow and wind until, in the far distance, we make out the conquering army, with the tiny figure of Hannibal on his elephant. There are no solid forms at all. That the public accepted so nearly abstract an image as a finished picture is due both to the title and to the explanatory verses from his own meandering poem “The Fallacies of Hope,” which Turner published in the exhibition catalog. But British viewers would also have recognized the topicality of the subject, for they would have seen at once that it refers to Napoleon’s invasion of Italy, and to the eventual destruction of all tyrants, whether in ancient Rome or modern France.

2.

An exhibition that can be seen at Tate Britain in London until January 11 before traveling to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth gives us extraordinary insight into Turner’s working methods by emphasizing the enormous gulf that exists between his preliminary works on paper and his finished oil paintings. By tracing a single theme in Turner’s art—his depiction of the city of Venice—and by including Venetian views by Turner’s contemporaries, the show helps us to understand the particular qualities that made Turner inimitable among British artists. So closely is Turner’s work associated with Venice that it comes as a surprise to learn how little time he actually spent there. He was already forty-four years old when he saw the city for the first time in 1819. But it was not then the place of artistic pilgrimage it was soon to become, and so he stayed for only five days before pressing on to Rome and Naples, where he was to spend almost three months. What is more, his initial encounter with Venice in 1819 germinated in Turner’s consciousness for fourteen years before it resulted in an oil painting with a Venetian subject. His second visit, in 1833, lasted nine days. On the third and last of 1840, he was there for two weeks.

On his first visit he took in all the tourist sites, frantically drawing palaces, churches, campaniles, canals, and bridges—hardly pausing to paint because that could be done back home. Spellbound, he covered about 160 pages in his sketchbooks with tiny pencil studies that have the indiscriminate quality of a modern-day tourist let loose in Venice with an instamatic camera. But early one morning, looking out over the basin of St. Mark’s, Turner stopped, took out his brushes and watercolors, and made three panoramic views showing the Customs House and the churches of San Giorgio Maggiore and San Pietro di Castello—their domes and towers silhouetted against the soft yellow skies and mirrored in the waters below. In a fourth watercolor he turned around and painted the Campanile of St. Mark’s and the Doge’s Palace.

Advertisement

At this point, it was rare for Turner to paint in color directly from nature. But that morning, it is as though he needed to transpose onto paper as swiftly as possible the limpid beauty he saw before his eyes, using pure color, without the intermediary step of drawing. These luminous studies of architecture dissolving in light and water were ultimately to inaugurate a new phase in his art. Broadly speaking (and with Turner, generalizations should be made with caution), we can say that until this time he had viewed objects in terms of volume and outline, tinted with color. Over the next decade, color began to predominate over form. By the time of his last visit to Venice in 1840, light and color infuse the material world with life.

As Ian Warrell makes clear in his carefully documented essay in the catalog for the Tate exhibition, on Turner’s two subsequent stays in Venice he worked primarily in watercolor. In one gallery, the watercolors made on his 1840 tour are hung in such a way that we can follow Turner’s progress as he moves down the Grand Canal from the Rialto to the Basin of St. Mark’s. In virtually every one, Turner draws the architecture in pencil and then covers this underdrawing with washes of pale color. Often he dips a pen in black pigment to create a row of little windows or awnings, and he can summon up a flotilla of moored gondolas with a few flicks of a tiny brush, like a Chinese calligrapher. For the most part, he views the palaces on either side of the Grand Canal obliquely, just as you see them from a gondola or vaporetto, but every so often he confronts his motif head on, as in his study of the monumental palaces the Grimani and dei Cavalli, two Renaissance matriarchs standing guard on either side of a narrow canal.

Most of the watercolors from the 1840 visit were painted back in Turner’s bedroom at the Hotel Eu-ropa. He may have set up a table on the roof in order to paint the views over St. Mark’s, the Campanile, and the Doge’s Palace because these have the sketchiness and immediacy you would expect of works made directly while observing the subjects. By contrast, he worked either from memory or from pencil sketches when he came to execute the night scenes in St. Mark’s Square, as well as a study of fireworks cascading down over the church of the Salute, and a painting of a gondola racing through turbulent waves, chased by the indigo clouds of a breaking storm. In a smaller gallery at Tate Britain, called “Venice After Dark,” we can follow Turner as he strays down back alleys and small canals, records a performance at the theater, and expresses in paint his sheer delight in his hotel bedroom’s intense blue walls, yellow bed hangings, painted ceiling, and the view of the Campanile through an open window. Most of these works accurately record real sights; a few are partly imaginary. What they all have in common is that they were made for Turner’s private use or delectation. Not one was exhibited or sold during his lifetime.

Though we may sometimes prefer the swift watercolors to the more labored oils, the watercolors are lesser works of art because they can tell us only one thing: what Turner saw at that moment, on that day, in those atmospheric conditions. You can only understand why Turner is to British art what Shakespeare is to British literature by looking at the oils. Here, far more than in the watercolor studies, we can see how Turner’s great mind and imagination, imbued from an early age with the teachings of Sir Joshua, invested his landscapes and cityscapes with layer upon layer of meaning. For Venice existed in Turner’s imagination long before he actually visited it, through his familiarity with Canaletto’s etchings, and his knowledge both of Shakespeare’s Venetian plays and of Byron’s Childe Harold. As he moved through Venice, every part of the city and its lagoon spoke to him of the art of the past, of history, and of literature.

When he showed his first Venetian oil, Bridge of Sighs, Ducal Palace and Custom-House, Canaletti painting, at the Royal Academy in 1833, he set the scene in the previous century, in a subject that challenged his audience to compare his work with the most celebrated of all view painters, Canaletto. Unlike more prosaic contemporaries like Clarkson Stanfield, Samuel Prout, or even Richard Parkes Bonington, in Turner’s oils Venice is a timeless place, a place where it is not always possible to distinguish the past from the present, or the real from the imaginary, and where squalor exists side by side with unearthly beauty. It is the way in which Turner can turn an ordinary view into a moralizing meditation on history, art, or poetry that sets him apart from other artists who have painted the city. If he could not fully express his complex thoughts about the city in one canvas, he frequently painted two—linked pairs in which he typically contrasted morning and evening, hot and cold colors, past and present.

The best examples also happen to be two of the most beautiful oil paintings in the show. Venice of 1834 shows gondolas and sailboats in front of the Customs House and church of San Giorgio under blue skies on a golden summer’s day. Its companion picture, Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Night, exhibited at the Royal Academy the following year, is a night scene set on the Tyne, the light coming from the watery moon and flaming torches. By contrasting the two scenes, Turner meditates on Venice’s decline as a European power, and compares her fate to that of Great Britain’s ascendant maritime empire. Turner here is almost responding to William Blake’s protests against the Industrial Revolution. Far from condemning industry, he sees both virtue and beauty in the sight of men working long into the night to attain their country’s industrial preeminence. Far from idealizing Venice, he suggests that her external beauty masks moral lassitude or even corruption. Ravishing as the view in Venice is, if you look down to the picture’s foreground, you see garbage floating in the water.

3.

Recent commentators tend to see Turner’s paintings and finished watercolors as more or less incomprehensible without the help of art historical scholarship to unravel their myriad literary and historical allusions.2 In the words of Turner’s latest biographer, James Hamilton, the paintings need to be read “to their every last nuance for one to reach the fullest understanding of the meaning….” As far back as 1844, John Ruskin predicted that Turner’s name would one day be “placed on the same impregnable heights with that of Shakespeare.” Hamilton agrees, and goes on to say that

there are few, if any, whims in Turner; his manner of painting, his subject matter, his relationships with fellow artists living or dead, and his methods of experimentation are deeply rooted in the events and experiences of his youth and young manhood, and if we find a puzzling apparent departure in middle or late Turner, its roots can invariably be found in his early career.

In other words, you can’t understand the paintings without knowing about the life.

Certainly few artists have been able to express emotion with the precision that Turner does. In his watercolor depicting the funeral of Thomas Lawrence, the rhythmically repeated notes of black—in the doors of St. Paul’s Cathedral, in the waiting hearse, the plumed horses, and the shuffling cortege of mummers—are like the tolling of a great bell. When the artist David Wilkie (one of the very few positively likable characters to emerge from Hamilton’s biography) died on the journey home from the Middle East, Turner painted a visual threnody to his friend, Peace—burial at sea (see illustration on page 20). In the torchlight, Wilkie’s coffin is lowered into the water against the near-black of the paddle steamer’s sail. When a friend objected to the darkness of the sails, Turner replied, “I only wish I had any color to make them blacker.”

As both these examples suggest, many of Turner’s closest friends were artists. After reading Hamilton’s life, this may come as a surprise. Hamilton is good on the power politics of the English art world in which Turner maneuvered so skillfully. At the beginning, he didn’t hesitate to use bribery to help him gain admittance to the Royal Academy. Once elected, he cast aside his mask of geniality. When the Royal Academician Sir Francis Bourgeois called him “a little reptile,” Turner shot back that Bourgeois was “a great reptile, with ill manners!” Rude, ruthless, competitive, and mean: Hamilton has a hard time trying to see the good side of the young Turner. Still, as the old brute mellows with age, a more charitable side of his personality emerges, and his affection for friends and patrons such as Wal-ter Fawkes or Lord Egremont, like the depth of his grief for Lawrence and Wilkie, almost makes us warm to him.

But no act of kindness or endearing personality trait cited by Hamilton can disguise the fundamental sordidness of Turner’s life—the squalid studio (overrun with cats, and its broken skylight open to the rain), the mother whom he abandoned to her fate, the tiresome father whom he used as his factotum, the greed, the parsimony, the illegitimate children whom he failed to support, the viciously competitive professional practices.3 When Turner visited Delacroix in his Paris studio, it is the last three words of the unimpressed Frenchman’s description that leap out. Turner, he wrote, had the “appearance of an English farmer, black clothing, quite coarse, big shoes and a cold hard demeanour.” Turner raised himself up from the working class, but never acquired a gentility to match the fortune and status his art gained for him. As a result, he was never granted the knighthood he deserved as the most celebrated artist of the age.

And here we come to the main difficulty with Hamilton’s biography. Although it is well researched and fluently written, there doesn’t seem to me much point in writing a life of Turner. When not painting, Turner traveled, lectured, prepared for exhibitions, and engaged in nonstop business dealings with patrons and engravers. His rigid schedule hardly varied from decade to decade. From October to April, he worked in his London studio preparing for the annual Royal Academy exhibition, then set off on his travels in July or August. Told in chronological order his life consists of one painting and sketching expedition after another. An earlier biographer, A.J. Finberg, confided to his son, “The real trouble…is…that Turner is a very uninteresting man to write about…. The only interesting thing about him is that he was the man who painted Turner’s pictures.”4

This does not mean that the facts of Turner’s life are not worth knowing about—but they are of interest only insofar as they relate to the paintings. But something peculiar happens to people who become involved in Turner studies: they begin to consider virtually everything this deeply flawed man did, said, or wrote worth recording. Particularly puzzling to me is the importance accorded to Turner’s long unpublished poem “The Fallacies of Hope.” For all his intelligence, the artist simply did not have the ability to express ideas clearly through the written word. One editor, faced with one of Turner’s poems to print as a caption to an engraving, wrote:

Mr Turner’s account is the most extraordinary composition I have ever read. It is impossible for me to correct it, for in some parts I do not understand it. The punctuation is everywhere defective, and here I have done what I could…. I think the [revision] should be sent to Mr Turner, to request his attention to the whole, and particularly the part that I have marked as unintelligible. In my private opinion, it is scarcely an admissible article in its present state.

All of the Fallacies is bad poetry. Much of it is incomprehensible. And yet Hamilton can’t resist quoting lines like

Of Horizontal strata, deep with fissure gored

And far beneath the watry billows cored

In caverns ever wet with foam and spray

Impervious to the blissful light of day

Blocked up by fragments or by falling give

a rocky Isle in which the sea maids live

Bear their rough forms and brave the utmost rage

Of storms that stain our British parish page….

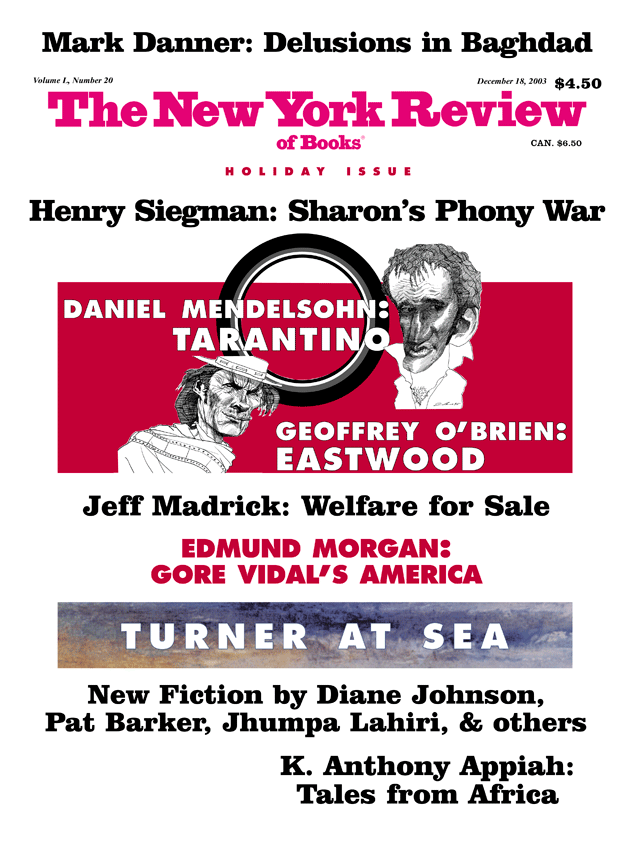

If the biography gets bogged down in a tedium of unnecessary detail and in occasional flights of fanciful interpretation, Hamilton is much better in a recent exhibition catalog in which he has the space to concentrate on the paintings. In Turner: The Late Seascapes he looks at a distinct group of pictures painted between the mid-1820s and the 1850s. A fair number of these landscapes are inspired by Dutch old masters such as Jan van Goyen and Willem van de Velde the Elder. Many are also dramatic narrative subjects, and reflections on contemporary political issues. To take just one example, The Prince of Orange, William III, Embarked from Holland, and Landed at Torbay, November 4th, 1688, after a Stormy Passage was exhibited in 1832, at a time of turmoil in British politics.

In this very year the Reform Bill, which widened the franchise and put limits on aristocratic and landed patronage, led to widespread public disorder. Turner’s title reminded his viewers that at an earlier period of crisis, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the British had brought in a Dutch monarch to supplant the ousted Stuart king. But the reference seems to have gone unnoticed—at least no critic of the Royal Academy show that year made any reference to the relevance of the picture’s title. It is a telling comment on the way we now look at Turner’s art that only in recent years have we come to understand how Turner meant his subject to be understood. Fully one third of Turner’s oils are sea pieces—indeed the first oil painting exhibited at the Royal Academy was Fishermen at Sea of 1796. The genre therefore forms a major theme in Turner’s work, one that is celebrated too in “‘The Sun Rising Through Vapour’: Turner’s Early Seascapes,” a show at the Barber Institute in Birmingham, England, which complements Hamilton’s study by concentrating on the early marine pictures. All four shows add up to a belated national tribute, two years after the 150th anniversary of his death, to the greatest British artist who ever lived.

This Issue

December 18, 2003

-

1

See Turner: The Great Watercolours, edited by Eric Shanes (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2000), cat. 8. ↩

-

2

See, for example Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence (Yale University Press, 1987), and John Gage, J.M.W. Turner: “A Wonderful Range of Mind” (Yale University Press, 1987). ↩

-

3

The most notorious incident occurred at the 1832 Royal Academy exhibition. When Turner found his pale seascape hanging next to his rival John Constable’s vividly colored The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, he left the room, returned with his palette, and without saying a word put a round daub of red pigment in the foreground of his picture. Later, he repainted the disc into the shape of a buoy. The intensity of the crimson, intensified by the cool green surrounding it, made even the colors in Constable’s picture look weak. After Turner left, all the stricken Constable could say was, “He has been here, and fired a gun.” ↩

-

4

“The real trouble…is…that Turner is a very uninteresting man to write about. There is nothing picturesque, romantic or exciting either in his character or in his life. His virtues and defects are all on the drab side. He was thoroughly plebeian in all things, a common workman and tradesman… the only interesting thing about him is that he was the man who painted Turner’s pictures.” Quoted by Andrew Wilton in Turner and His Time (Thames and Hudson, 1987), pp. 6–7. ↩