In its official count of the number of “hostile terrorist attacks,” the Israeli government includes any kind of attack, from planting bombs to throwing stones. By this count suicide bombings make up only half a percent of the attacks by Palestinians against Israelis since the beginning of the second intifada in September 2000. But this tiny percentage accounts for more than half the total number of Israelis killed since then. In the minds of Israelis, suicide bombing colors everything else.

According to B’tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, the number of Israelis killed by Palestinians between September 29, 2000, and November 30, 2002, is 640. Of those, 440 are civilians, including 82 under the age of eighteen. Some 335 were killed inside Israel proper, the rest in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The Palestinians also killed 27 foreign citizens during this period. The number of Palestinians who were killed by Israelis between September 29, 2000, and November 2002 was 1,597, 300 of them minors. Since March there have been no accurate numbers for the occupied territories; B’tselem estimates that during Sharon’s operation “Defensive Shield” in March and April 2002, some 130 Palestinians were killed in Jenin and Nablus alone.

From the signing of the Oslo agreements in 1993 until the beginning of August 2002 we know of 198 suicide bombing missions, of which 136 ended with the attackers blowing up others along with themselves. This year has seen by far the greatest concentration of the attacks, about one hundred by the end of November.

In other attacks by Palestinians—called “no-escape” attacks—the chances of staying alive after, say, firing on an army position or a settlement are next to zero. Over forty settlers were killed by such attacks this year. The no-escape fighters strike mainly targets in the occupied territories; the suicide bombers are most likely to attack targets inside Israel’s pre-1967 borders. In the willingness to sacrifice their own lives there is very little difference between the suicide bombers and the no-escape attackers. But the impression a suicide bombing leaves on Israelis is very different from a no-escape attack. The suicide bombers make most Israelis feel not just ordinary fear but an intense mixture of horror and revulsion as well.

In this conflict practically every statement one makes is bound to be contested, including the description of the attackers as suicide bombers and the victims as civilians. Islamic law explicitly prohibits suicide and the killing of innocents. Muslims are consequently extremely reluctant to refer to the human bombers as suicide bombers. They refer to them instead as shuhada (in singular: shahid), or martyrs. Palestinians are also reluctant to use the expression “Israeli civilians,” which implies that they are innocent victims. Even if they are Israeli dissidents they are not regarded as such. In a recent attack by Hamas at the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, one of the victims, Dafna Spruch, had been active in one of the most fearless peace protest groups in Israel, Women in Black. Hamas dealt with this simply by claiming that she belonged to Women in Green, a ferocious anti-Palestinian right-wing organization. As such, she was not innocent.

Spokesmen for Hamas justify the killing of civilians by saying it is a necessary act of defense—the only weapon they have to protect Palestinian women and children. “If we should not use” suicide bombing, the Hamas leaders announced this November, “we shall be back in the situation of the first week of the Intifada when the Israelis killed us with impunity.”

A report by Amnesty International in July 2002 summarizes the arguments cited by the Palestinians as reasons for targeting civilians. The Palestinians claim that

they are engaged in a war against an occupying power and that religion and international law permit the use of any means in resistance to occupation; that they are retaliating against Israel killing members of armed groups and Palestinians generally; that striking at civilians is the only way they can make an impact upon a powerful adversary; that Israelis generally or settlers in particular are not civilians.1

The report finds these reasons unacceptable. It considers Israeli violations of human rights so grave that many of them “meet the definition of crimes against humanity under international law.” But it also concludes, “The deliberate killing of Israeli civilians by Palestinian armed groups amounts to crimes against humanity.”

Throughout the twentieth century the nineteenth-century taboo on targeting and killing civilians has been eroding. In World War I only 5 percent of the casualties were civilians. In World War II the figure went up to 50 percent and in the Vietnam War it was 90 percent. Amnesty International is making an admirable effort to restore the prohibition against targeting and killing civilians. Its report, rightly, does not make any moral distinction between those who kill themselves while killing civilians and those who spare themselves while killing.

Advertisement

My concern with the suicide bombers here is to understand what they do and why they do it and with what political consequences. To put the matter briefly, it is clear that there will be no peace between Israel and Palestine if suicide bombings continue. It is not clear that there will be peace if they stop, but there would at least be a chance for peace.

1.

In the Middle East, suicide bombing was first used by the Hezbollah in Lebanon. From November 1982, when a suicide bomber destroyed a building in Tyre, killing seventy-six Israeli security personnel, through 1999, the year the Israelis withdrew from Lebanon, the Hezbollah carried out fifty-one suicide attacks. In October 1983 it took only two suicide explosions—one killing 241 American servicemen, mostly Marines, and the other killing 58 French paratroopers—to force the Americans and the French out of Lebanon. It wasn’t until ten years later that the first Palestinian suicide bombing took place.

In other parts of the world, soldiers of one army—the Japanese kamikaze, or the Iranian basaji—have been willing to commit suicide in bombing another army. Some of the Tamil Black Tigers of Sri Lanka have killed themselves in attacks on politicians and army installations, and they have done so with utter disregard for the lives of civilians who happened to be around. But the Palestinian case is the only one in which civilians of one society regularly volunteer to become suicide bombers who target civilians of another society. They may be chosen by Hamas or Islamic Jihad to carry out a suicide bombing mission, but for the most part the volunteers have not been active members of these organizations.

We can see how the practice of suicide bombing evolved. The Palestinians started using suicide bombers as a weapon not to emulate the Hezbollah strategy in Lebanon but in reaction to a specific event. According to Ha’aretz’s Daniel Rubinstein, the most authoritative Israeli commentator on the Palestinians, the bombing began with the so-called “war of the knives.” On October 8, 1990, hundreds of worshipers came out of the al-Aqsa mosque throwing stones at the Israeli police and at the Jewish worshipers praying by the Wailing Wall nearby. The Israeli police reacted by firing on them. Eighteen Palestinians were killed by Israelis in the clashes that day (in comparison, four were killed in the skirmishes that started the current intifada). Hamas called for jihad, or holy war, but no organized response followed. However some Palestinians tried to seek revenge on their own. The first, Omar abu Sirhan, came with a butcher’s knife to my neighborhood in Jerusalem and slaughtered three people. He later said he had little hope of surviving his self-appointed mission. After he was caught, he said he saw the Prophet in his dream and was ordered by him to avenge those who were killed in the al-Aqsa mosque. Hamas immediately adopted abu Sirhan as a hero. It sensed the potential of such avenging attacks and soon transformed that potential into organized human bombers.

The one thing that Palestinian suicide bombers have in common is that they are all Muslims. No Christians have been involved. Hamas and Islamic Jihad, for their part, say that suicide bombing is a religious duty and these two Islamic organizations for years monopolized the bombings. They would have nothing to do with Christians and they have long been hostile to the Palestinian nationalists of Arafat’s Fatah movement. But the monopoly ended once the nationalists of the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, which is affiliated with Fatah, joined in. It is unclear whether those who act under the auspices of the al-Aqsa Brigade, who have in the past emphasized nationalism, not Islam, as central to their movement, would now also regard their missions as religious acts of martyrdom.

In the account of the struggle against Israel given by political Islamists there are two elements. One is the holy war, jihad, which suicide bombers consider not just a war against the oppressive occupation of Palestinian land but one fought in defense of Islam itself. The other element is martyrdom: those who sacrifice themselves in the holy war are martyrs. From the many statements by the suicide bombers themselves, it is the idea of the martyr, the shahid, rather than the idea of the jihad that seems to capture the imagination of the suicide bombers. The idea of the jihad may give the struggle an Islamic content; but the idea of the shahid seems more powerful.

While the language used by the bombers and their organizations is always distinctly Islamic, the motives of the bombers are much more complicated, and some mention more than one motive for their act. Mahmoud Ahmed Marmash, a twenty-one-year-old bachelor from Tulkarm, blew himself up in Netanya, near Tel Aviv, in May 2001. On a videocassette recorded before he was sent on his mission, he said:

Advertisement

I want to avenge the blood of the Palestinians, especially the blood of the women, of the elderly, and of the children, and in particular the blood of the baby girl Iman Hejjo, whose death shook me to the core…. I devote my humble deed to the Islamic believers who admire the martyrs and who work for them.

In a letter he left for his family he wrote, “God’s justice will prevail only in jihad and in blood and in corpses.” Such references to jihad are not as common as references to revenge. Having talked to many Israelis and Palestinians who know something about the bombers, and having read and watched many of the bombers’ statements, my distinct impression is that the main motive of many of the suicide bombers is revenge for acts committed by Israelis, a revenge that will be known and celebrated in the Islamic world.

Most of the suicide bombers say as much themselves, but it is impossible to generalize about them. At first, when Hamas and its military branch, the Izz al-Din al-Qasam Brigade, and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad took responsibility for sending virtually all of the suicide bombers, the bombers were young unmarried males. But since December of last year, when the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade joined in, the bombers have included both men and women, villagers and townspeople, bachelors and married people. The bombers are young and not so young, educated and not educated, from poor families and from relatively well-off ones. Still, most of the bombers are young unmarried men, between seventeen and twenty-eight, and more than half of them come from refugee camps, where the hatred of Israel is strongest. From the accounts of them in the press and the statements by those who know them, the suicide bombers are not what psychologists call suicidal types—they are not depressed, impulsive, lonely, and helpless, with a continuous history of being in situations of personal difficulty. Nor do they seem driven by economic despair. A study conducted by the Israeli army analyzing the background of eight bombers from the Gaza strip showed that they were relatively well- off.2 I have never seen a public or private statement by a suicide bomber that mentions his own economic situation or that of the Palestinians generally as a reason for his action.

It is often said that the bombers are driven by their own feelings of hopelessness and despair about the situation of the Palestinians; but this seems open to question. It is true that the Palestinian community is in a state of despair, but this does not mean that each and every person, in his or her personal life, is in despair—any more than the fact that the US is relatively rich makes each American rich. The despair in communities explains the support for the suicide bombers, but it does not explain each person’s choice to commit suicide by means of a bomb.

Hussein al-Tawil is a member of the People’s Party, formerly the Communist Party, in the West Bank. His son Dia blew himself up in Jerusalem, in March 2001, on a Hamas mission. Amira Hass, an Israeli journalist for Ha’aretz who has intimate knowledge of life in the occupied territories, talked to friends of the father, former Communists, and some of the son’s friends, who are members of the Hamas group at Beir-Zeit University. The two groups of friends don’t mix. The father’s friends claim that Dia was “brainwashed” by Hamas, causing great pain to a father who loved him and did what he could to send his son to the university to study engineering. For Dia’s friends from Hamas, who chanted at his funeral, on the other hand, he is a heroic martyr to the Islamic cause.

Their reaction resembles that of Raania, the pregnant wife of the Hamas militant Ali Julani and a mother of three. Her husband took part in a no-escape attack in Tel Aviv. “I am very proud of him. I am even prouder for my children, whose father was a hero. I want to tell the Israelis that I support my husband and I support people like him.” Was she angry with him for leaving his children fatherless? “He left us in the mercy of God. He was raised as an orphan and the way he was raised so his children will be raised.”3 A man named Hassan, whose son blew himself up in a Tel Aviv discotheque, had a similar reaction: “I am very happy and proud of what my son did and I hope all the men of Palestine and Jordan will do the same.”4

Most families seem to be similarly proud of their kin who become shuhada. According to a verse in the Koran that is quoted often by the shahid’s family and friends, the shahid does not die. From a religious point of view, a crucial element in being a shahid is purity of motive (niyya), doing God’s will rather than acting out of self-interest. Acting because of one’s personal plight or to achieve glory are not pure motives. Most of the families of the shuhada accordingly want to present their suicides in the best possible light. To honor and admire the family of a shahid is a religious obligation and the family’s status is thus elevated among religious and traditionalist Palestinians. In addition families of shuhada receive substantial financial rewards, mainly from Gulf countries and especially from Saudi Arabia, but also from a special fund created by Saddam Hussein. So far as I know, no one who has followed the history of the shuhada closely believes that money is what makes their families support them, although it helps.

2.

According to statements by Hamas and Islamic Jihad, the suicide bomber is willing to die as an act of ultimate devotion in a “defensive” holy war. There are two senses of jihad: a holy war to spread Islam, and a defensive holy war that takes place when what is perceived as the domain of Islam is threatened by invaders. From a radical Islamic point of view, Israel itself, as a Jewish state, is an invasion of the domain of Islam. Worse, according to the platform of Hamas, Israel is a state composed of heretics established on land that has been divinely granted to Islam (waqf). Battling Israel is one of the most urgent tasks of the defensive jihad. It is a duty that should be undertaken by any Muslim, man or woman, and it overrides any other obligation. The idea of defensive jihad can easily be understood as carrying out the national goal of “freeing the land” from the presence of the invaders.

In October, Iyaat al-Haras, a high school student from Bethlehem, explained on a videocassette that her suicide mission was an act in defense of both the mosque of al-Aqsa and of Palestine. This message can be interpreted both in national and in religious terms. Judging solely from her video it is hard to tell whether religion or nationalism is the stronger motive. But since she was dispatched by the nationalist group associated with Fatah, and since the organization would have taken part in formulating her statement, we can surmise that the message was deliberately ambiguous. Whether suicide bombers act for national or for religious reasons or from different mixtures of both is often difficult to tell. The predominantly nationalist and predominantly religious groups are eager to keep it that way, both for the sake of Palestinian unity and because each camp is trying to gain popularity within a community that is made up of both Islamists and nationalists.

As I have said, the main motivating force for the suicide bombers seems to be the desire for spectacular revenge; what is important as well is the knowledge that the revenge will be recognized and celebrated by the community to which the suicide bomber belongs. In many cases the bombers say they are taking revenge for the death of someone quite close to them, a member of their family or a friend. In May 2002, Jihad Titi, a young man in his twenties from the refugee camp of Balata near Nablus, collected the shrapnel of the shell that killed his cousin, a Fatah commander in the camp whom the Israeli army had targeted and killed. Titi stuffed the shrapnel pieces into the containers of TNT he carried and killed an elderly woman and her granddaughter while blowing himself up. In the early morning of November 27, 2001, Tyseer al-Ajrami, a man in his twenties, blew himself up, killing an Israeli policeman in a building used as a gathering place for Palestinian workers. Ajrami was from the Gabalia refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, married and a father of three. In his will he explained his deed as, among other things, a retaliation for the killing of five children in Khan Yunis the week before.

It is in fact a common practice among the bombers to mention a very specific event or incident for which they take revenge. Darin abu-Isa, a student of English literature who blew herself up in March 2002, lost her husband and her brother in the current intifada; her family says that she did it to avenge their deaths.

The bombers seek vengeance not just by killing Jews, but by instilling fear in them as well. Anwar Aziz, who later blew himself up in an ambulance in Gaza in 1993, said: “Battles for Islam are won not through the gun but by striking fear into the enemy’s heart.” The writer Nasra Hassan, a Muslim from Pakistan, was told by a dispatcher that spreading fear is as important as killing. But the urge for revenge in itself does not explain why people become suicide bombers. After all there are other, more conventional, ways of taking revenge without taking one’s own life. Vengeance through suicide bombing has, as I understand it, an additional value: that of making yourself the victim of your own act, and thereby putting your tormentors to moral shame. The idea of the suicide bombing, unlike that of an ordinary attack, is, perversely, a moral idea in which the killers, in acting out the drama of being the ultimate victim, claim for their cause the moral high ground.

In preparing the shuhada for their mission, the idea of winning an instant place in paradise used to have a major part. In a remarkable account, Nasra Hassan talked to a member of Hamas who described to her how people are given instructions on how to act as a shahid: “We focus his attention on Paradise, on being in the presence of Allah, on meeting the Prophet Muhammad, on interceding for his loved ones so that they, too, can be saved from the agonies of Hell, on the houris“—i.e., the heavenly virgins. When she talked to a volunteer who was ready to carry out his mission, but for some reason stopped, he told her about the sense of the immediacy of paradise: “It is very, very near—right in front of our eyes. It lies beneath the thumb. On the other side of the detonator.”5

In the current intifada, the time spent in instructing volunteers has apparently become much shorter than in the past. Tabet Mardawi, a dispatcher for Hamas, says that there is never a lack of volunteers now. “We do not have to talk to them about virgins waiting in paradise.”6 Talking of the promise of paradise, a skeptical young man in Gaza said to Amira Hass, “If it were true, why is it that the experts and the leaders of the Islamic movements are not all running out to be killed themselves and are not sending their own children on these missions?” But I do not necessarily see the dispatchers as manipulative cynics who dupe confused youngsters into believing something that they themselves do not quite believe. Whatever their Islamic belief or suspension of disbelief, they seem to have too many other motives for acting as they do against the Israelis, whom they perceive as the hated conquerors of the land.

If it is easy to question whether being a shahid secures an immediate entrance to paradise, no one can doubt that being a shahid secures instant fame, spread by television stations like the Qatar-based al-Jazeera and the Lebanon-based al-Manar, which are watched throughout the Arab world. Once a suicide bomber has completed his mission he at once becomes a phantom celebrity. Visitors to the occupied territories have been struck by how well the names of the suicide bombers are known, even to small children.

Before the bombers are sent on their mission, all the dispatching organizations make videotapes in which the would-be shuhada read a statement describing their reasons for sacrificing their lives. They do this while wearing the organization’s distinctive headcovering and often with something in the background identifying the organization—for example, a picture of the al-Aqsa mosque, a copy of the Koran, and sometimes a Kalashnikov. The video may be conducted as an interview, with a masked member of the dispatching organization asking questions. We are told in some published accounts that before setting off, the volunteers watch their video again and again, as well as videos of previous shuhada. “These videos encourage him to confront death, not to fear it,” one dispatcher told Nasra Hassan. “He becomes intimately familiar with what he is about to do. Then he can greet death like an old friend.”

On the day of the mission the video is sent to television stations to be broadcast as soon as the organization takes responsibility for the bombing. Posters and even calendars are distributed, with pictures of the “martyr of the month.” The shahid is often surrounded by green birds, which are an allusion to a saying by Muhammad, that the martyr is carried to Allah by green birds.

While resentment of the extreme economic misery in which Palestinians live, especially in Gaza, partly explains the support for suicide bombing among the Palestinian population, suicide bombings have only further devastated the Palestinian economy. Some 120,000 Palestinian workers, over 40 percent of the Palestinian work force, were employed in Israel in 1993. The suicide bombings of 1995 and 1996 then led to the decision of the government to close off the territories and drastically reduce the numbers of Palestinians working in Israel. Many of them were eventually replaced by foreign workers from Thailand, Romania, and various African and other countries. By 2000 the Palestinian workers were back at work in Israel, many of them as illegal workers. Their number is estimated to have reached about 130,000, which by then was a lower percentage of the Palestinian work force than it was in 1993.

The second intifada, and especially the recent wave of suicide bombings, once again reduced drastically the number of workers from the territories. It also stopped the flow of goods and services to and from Israel, the only serious market for Palestinian exports. The result has been devastating for the Palestinian economy. The Palestinian Authority, which subsists on donations from abroad, is the only remaining employer to speak of.

Although there is much talk about the corruption within the Authority, I doubt that it is more corrupt than many post-Communist or third-world countries. But in trying to create an economy that could lay the foundations for Palestinian independence, the Authority has failed miserably. The Palestinians are almost completely dependent on Israel, not only for jobs but for the only large market for their produce. Moreover, in a desperate response to the suicide bombings, Israel is now erecting a fence separating Israel proper from the occupied territories. This will likely leave the Palestinian economy crippled beyond repair since a large proportion of Palestinian workers will be cut off from any jobs.

Both Hamas and Islamic Jihad want to convey the message that Islam has been divinely endowed with the entire land of Palestine, which includes all of Israel, and that this sacred endowment is not subject to negotiation. Sending suicide bombers into Israel proper rather than confining them to the occupied territories gives a clear signal that the two Islamic organizations do not accept the distinction between the pre-1967 land of Israel and the land that was conquered by Israel in 1967. All of it belongs to the Palestinians. Arafat’s Fatah accepted the distinction in 1988, and it was subsequently incorporated in the Oslo agreements of 1993. Once the Fatah organization, which had since its inception been a secular, national movement, joined forces with the Islamists at the end of 2001 in sending suicide bombers into Israel proper, the question arose whether its leaders had begun to share the message of erasing the distinction between the pre-1967 land and the land conquered in the 1967 war.

The Palestinian mantra “end to the occupation” has thus become equivocal about what is under occupation. According to the interpretation of Hamas and other Islamic groups, the entire state of Israel is essentially an occupation and Israel should therefore be annihilated. Thus, while many Palestinians would probably welcome a separate state of their own, the religious belief in jihad may have prepared the way for some nationalists, and especially for militants who are not politically minded, to subscribe to the belief that all of Palestine is under occupation; hence an end to the occupation means the end of Israel.

A major question concerning the dispatchers of the suicide bombers is where they stand in their own organization and who gives them orders, particularly the dispatchers who belong to the two organizations associated with Arafat, the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade and the Tanzim. If leaders, especially Arafat, decide that suicide missions must stop, will the dispatchers obey them?

In December 2001, Arafat delivered a speech in which he called for the terror to stop. He had done this several times before, but always with what seemed a wink. On that occasion, he seemed serious. In the aftermath of September 11, Arafat, according to many reports, was desperate not to repeat his mistake of the Gulf War, when he sided with Saddam Hussein. When Colin Powell called for the future establishment of a Palestinian state, his speech was seen as an achievement for Arafat, at least among his followers. I have heard from well-informed Palestinian and Israeli sources that Arafat’s loyalists believed that Arafat wanted in December last year to regain control and to stop the suicide bombings. People close to Arafat also believed that this was clear to the Americans and to the Israelis.

Three weeks of calm followed. Then Sharon ordered the “targeted killing” of Arafat’s popular lieutenant, Raad Karmi, and Palestinian protests erupted throughout Israel and Gaza. Arafat’s activists became convinced that there was no way that they could reach even a limited understanding with Sharon; the only way to fight was to adopt Hamas’s tactic of using suicide bombers. It was at that point, my Palestinian sources told me, that Arafat’s people joined in the deadly game of dispatching suicide bombers into Israel proper. Arafat himself, they say, most likely went along with his activists so as not to lose his control over the Palestinian Authority. At the same time it seems likely that he lost control over the al-Aqsa Brigades. In its recent report, Human Rights Watch blames the Palestinian Authority for not acting to stop the terror strikes when it could—that is, before its security apparatus was destroyed by Israel in 2002.7

The suicide bombing got out of control—so much so that even Hamas became worried. There was outrage among Palestinians when Hamas started sending children on no-escape missions in the Gaza Strip. “I am going to be a shahid,” said fourteen-year-old Ismail abu Nida to his mother. She did not take him seriously but the child meant what he said and he was killed while taking part in an attack. The same happened to Yussuf Zakoot, fourteen, and Anwar Hamduna, thirteen. Hamas sensed, however, that the families were angry and, according to reports in the Palestinian press, it changed its recruiting tactics.

There was also a debate in 2002 between Sheikh Tantawi, a Cairo mullah whom most Palestinians consider the highest religious authority, and Sheikh Yassin, the spiritual and political founder and leader of Hamas. Sheikh Tantawi publically raised the issue of women suicide bombers after Arafat’s organization first began using them. He endorsed the participation of women in the suicide missions, saying that for the purpose of becoming shuhada they are, if their mission required it, allowed to disregard their roles as wives and mothers, not to mention to disregard the code of modesty. Sheikh Yassin did not contradict him on religious grounds, but he claimed that there was no need for women since there was already a surplus of male volunteers. The Palestinians I talked to said that they believed Yassin was worried not just that Hamas would lose its near monopoly of control over suicide bombing once the Fatah movement joined in; he also feared that suicide bombing would get out of hand and no longer serve a clear political purpose. So maintaining control over the people who actually dispatch the suicide bombers is a concern not just of Arafat but of Hamas as well.

If revenge is the principal goal, the suicide bombers have succeeded in hurting Israel very badly, and not just by killing and injuring many civilians. A more far-reaching success is that Israel’s leaders, in retaliating, have behaved so harshly, putting three million people under siege, with recurring curfews for unlimited periods of time, all in front of the world press and television, with the result that Israel may now be the most hated country in the world. This is hugely damaging to Israel, since the difference between being hated and losing legitimacy is dangerously narrow. Throughout the world, moreover, the suicide bombings have often been taken more as a sign of the desperation of the Palestinians than as acts of terror.

Israel claims it is fighting a war against the “infrastructure of terrorism,” but in fact it is destroying the infrastructure of the entire Palestinian society, not only its security forces and civil administration but much else as well. Many of the Israeli countermeasures are not only cruel but also irrational. As Ian Buruma recently reported in these pages, at the height of the olive-picking season, Israeli settlers have prevented Palestinian villagers from tending their own olive trees, fully aware that producing olive oil is one of the major activities of the Palestinian economy, the main source of income for many Palestinian villagers, and a source of pride as well.8 To make matters worse, settlers have not only been preventing the Palestinians from picking their olives but have been stealing them for themselves. This is simply one small example of a policy that is not just bad but also irrational.

Still, even when it is clear that Israeli policies toward the Palestinians are evil and irrational, it is far from clear how to confront the suicide bombers in ways that are rational and effective, as well as morally justified. This is why the moderate left is in trouble in Israel. The public is scared and in despair, and has no use for moralizing comments. It wants strategic solutions for stopping the suicide terror.

The members of the Israeli center-left, the only people who could secure for the Palestinians a state alongside Israel, used to believe in two propositions. First, the occupation since 1967 has been a moral and social disaster for Israel, let alone for the Palestinians, and it has to end. Second, if Israel withdrew to pre-1967 borders this would end the conflict. The second intifada convinced more and more Israelis, including many on the right, of the truth of the first proposition; the occupation cannot go on. On the other hand, the suicide bombers have convinced more and more Israelis, including many in the center-left, that the end of the occupation would mean neither an end to the conflict nor, more important, an end to the terror. In order to deal with an enemy organization you must assume that it cares about the lives of its own people. The suicide bombers convey to the Israelis the message that the resentment of the Palestinians, or at least of a good many of them, cannot be alleviated by Jews and that their demands cannot be met. This, at least, is the message that Hamas wants to send; but for a national movement like Fatah, if it still has national goals, it is suicidal to send such a message to Israelis.

Israelis and Palestinians take it as a foregone conclusion that there will be a war against Iraq. What the Palestinians fear—as Arafat has said publicly—is that Israel might use the smokescreen and confusion of a war to force as many Palestinians as it can to leave the West Bank, perhaps for Jordan. This is not an irrational fear, especially since the Labor ministers are no longer in the government, and Sharon presides over an ultra-right-wing cabinet. Should Palestinians be seen celebrating Iraqi missile strikes on Israel, and should a particularly destructive suicide bombing occur roughly at the same time, Sharon, in my view, would be quite capable of taking the opportunity to expel masses of Palestinians. In the meantime, as long as the Palestinians keep fighting, especially by attacking civilians, Israel will make the lives of the Palestinians even more miserable than they are now. Over 100,000 Palestinians have already left for Jordan since the beginning of the second intifada. If many more are forced to leave, that would suit Sharon just fine.

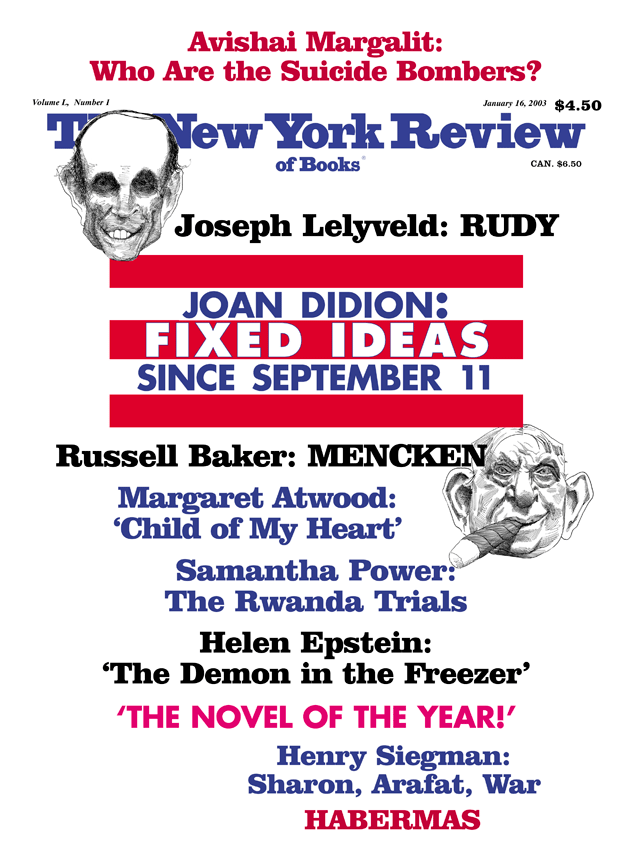

This Issue

January 16, 2003

-

1

Without Distinction: Attacks on Civilians by Palestinian Armed Groups (Amnesty International, July 2002). ↩

-

2

Amos Harel, Ha’aretz, January 22, 2002. ↩

-

3

Gideon Levy, Ha’aretz, August 17, 2001. ↩

-

4

Ha’aretz, June 4, 2001. ↩

-

5

“An Arsenal of Believers,” The New Yorker, November 19, 2001. ↩

-

6

Ha’aretz, April 23, 2002. ↩

-

7

Erased in a Moment: Suicide Bombing Attacks Against Israeli Civilians (Human Rights Watch, October 2002). ↩

-

8

“On the West Bank,” The New York Review, December 5, 2002. ↩