1.

The “Left Behind” books, the first of which was published in 1995 and the most recent in 2003, are the collaborative product of the Reverend Tim LaHaye, who, as the founder of Tim LaHaye Ministries and cofounder of the Pre-Trib Research Center, is in charge of ensuring that the fictional action conforms to his interpretation of biblical prophecy, and Jerry B. Jenkins, who, as the ghost or as-told-to writer on books by a number of celebrity authors (Billy Graham, Hank Aaron, Orel Hershiser, Nolan Ryan), actually does the writing.

In the past eight years the eleven installments that so far make up the series (Left Behind, Tribulation Force, Nicolae, Soul Harvest, Apollyon, Assassins, The Indwelling, The Mark, Desecration, The Remnant, and Armageddon, which made its first appearance on the New York Times fiction best seller list last April as number one) have together sold some fifty-five million copies, a figure which includes hardcovers and trade paperbacks and mass-market paperbacks and compact discs and audiobooks and e-books and comic (or “graphic”) books, but does not include either the study guides to the series (“using excerpts from the Left Behind novels and pointing readers to the prophetic passages of Scripture”) or the “Left Behind” military thriller series (“story lines of its own, but parallels the Left Behind books”). Neither does the fifty-five million figure include the merchandising of calendars and devotional readings, or the companion series for children between ten and fourteen, “Left Behind: The Kids,” thirty-some volumes in which “four teens are left behind after the Rapture and band together to fight Satan’s forces.”

The adult series, which offers essentially the same story line, begins as brisk enough reading. Captain Rayford Steele, a husband and a father and a senior pilot (for an American carrier) with secret lust in his heart for his flight attendant, Hattie Durham, has his 747 on autopilot over the Atlantic for a 6 AM arrival at Heathrow when Hattie pulls him into the galley to advise him that more than one hundred passengers, including every child aboard, have simultaneously vanished from the aircraft, leaving their clothes and belongings in neat piles on their seats. By the time Captain Steele, who has next learned that European airports have closed but whose fuel supply is fortunately still short of the point of no return (“I hope this puts your minds at ease somewhat,” he tells his remaining passengers), has managed to change course and return the 747 to O’Hare Chicago, it is clear that the disappearances on his flight were no isolated phenomenon: all over the world, millions of people have at the same instant vanished, leaving behind not only their clothes but also (one of many details in the series that tend to dampen its possibilities for wonder) their “eyeglasses, contact lenses, hairpieces, hearing aids, fillings, jewelry, shoes, even pacemakers and surgical pins.”

Any fundamentalist Christian would recognize that what has happened here is the Rapture, the moment when, according to the fundamentalist reading of Thessalonians (“first the Christian dead will rise, then we who are still alive shall join them, caught up in clouds to meet the Lord in the air”), true Christian believers will be taken up, or “raptured,” into heaven. Since all the true believers in the “Left Behind” series have vanished, however, those still on the scene are initially confused. O’Hare itself is littered with planes that crashed on approach when their pilots disappeared. Highways are clogged with the crashes of cars with disappeared drivers. CNN runs videotape showing the disappearance of a fetus from a woman in labor and the disappearance of a bridegroom as he slips the ring on the bride’s finger. Morgues and funeral homes report corpse disappearances.

Cameron “Buck” Williams, a young star reporter who happens to have been one passenger on Rayford Steele’s 747 who did not disappear, deftly restores his computer to working order (he had cut its wires on the plane in order to splice them to those inside the one operable telephone), and receives, from his executive editor in New York, a message reminding him, rather weirdly under the circumstances, of other stories in the hopper:

I know all anybody cares about is the disappearances. But we need to keep an eye on the rest of the world. You know the United Nations has that international monetarist confab coming up, trying to gauge how we’re all doing with the three-currency thing. Personally I like it, but I’m a little skittish about going to one currency unless it’s dollars. Can you imagine trading in yen or marks here? Guess I’m still provincial.

This communication appears on page 57 of the first volume of the series, Left Behind. Those brought up short by “the three-currency thing” (if not by the entire e-mail) may well not remember that we were told on page 9, where it was easy to skim past because Hattie Durham was still searching the lavatories for passengers missing their surgical pins, that “streamlining world finance to three major currencies had taken years” and that “a move was afoot to go to one global currency.” The editor’s message to Cameron Williams contains further alerts to the action to come, striking, bemusingly, the same note of editorial shoptalk:

Advertisement

Political editor wants to cover a Jewish Nationalist conference in Manhattan that has something to do with a new world order government…. Religion editor has something in my box about a conference of Orthodox Jews also coming for a meeting…. The other religious conference in town is among leaders of all the major religions, from the standard ones to the New Agers, also talking about a one-world religious order…. Need your brain on this. Don’t know what to make of it, if anything.

So. Even before Rayford Steele reaches home to find what he fears, that his devout wife and son are among the raptured and that he and his “skeptical” daughter (a Stanford student) have been left behind, we are already into monetary policy, the United Nations, “internationalism,” “the new world order,” the Realpolitik of the populist right. One of those left behind, the assistant pastor at the church attended by Rayford Steele’s wife and son (although not by Rayford himself, who, like many other characters in the series, had favored a church where “the people were nice, but it might as well have been a country club”), scours the Bible for clues, and calls a meeting to announce that “I’m onto something deep here and wanted to share it.” Not surprisingly, given the “Doctrinal Statement” of Dr. LaHaye’s Pre-Trib Research Center (“We believe that Christ will literally rapture His church prior to the 70th week of Daniel, followed by His glorious, premillenial arrival on the earth at least seven years later to set up His 1,000 year kingdom rule from Jerusalem over the earth”), the pastor has come to the conclusion that the Rapture marks the beginning of the seven years of the Tribulation. This “pre-tribulational” view, and in fact the innovative idea of the Rapture itself, shared by LaHaye and those other fundamentalist Christians who hold that believers can be taken into heaven without enduring the Tribulation, entered the evangelical ether in England around 1830 and reached American fundamentalists in the early twentieth century via Cyrus I. Scofield’s annotated Scofield Reference Bible, which taught the view in its notes. The assistant pastor lays it out:

The first twenty-one months [after the Rapture] encompass what the Bible calls the seven Seal Judgments, or the Judgments of the Seven-Sealed Scroll. Then comes another twenty-one-month period in which we will see the seven Trumpet judgments. In the last forty-two months of this seven years of tribulation, if we have survived, we will endure the most severe tests, the seven Vial Judgments. The last half of the seven years is called the Great Tribulation, and if we are alive at the end of it, we will be rewarded by seeing the Glorious Appearing of Christ…. Christ will come back to set up his thousand-year reign on earth…. Again, if I’m reading it right, the Antichrist will soon come to power, promising peace and trying to unite the world…. I fear it may be very soon. We need to watch for the new world leader.

In fact the Antichrist has already appeared, in the person of a previously obscure Romanian named Nicolae Carpathia, an advocate of global disarmament who has mysteriously emerged, under the shadowy guidance of a cartel of “international money men,” to unanimous acclaim. Cameron “Buck” Williams has already interviewed him. Hattie Durham is already angling for an introduction to him, and four books later, in Apollyon, will miscarry his child. (She wanted an abortion, but was discouraged from this course by Rayford Steele and the other new believers whose opposition to abortion apparently extends even to the child of the Antichrist.)

Carpathia, “a strikingly handsome blond who looked not unlike a young Robert Redford,” speaks at the United Nations, where he displays “such an intimate knowledge… that it was as if he had invented and developed the organization himself.” He is fluent in nine languages, “the six languages of the United Nations, plus the three languages of his own country.” He discusses the Last Judgment and the Second Coming at the opportunely scheduled ecumenical religious conference. He has a “scientific” explanation for the disappearances (“some confluence of electromagnetism in the atmosphere, combined with as yet unknown or unexplained atomic ionization from the nuclear power and weaponry throughout the world”), and dismisses (“compassionately”) a tentative suggestion that “this was the work of God, that he raptured his church”: “If there is a God, I respectfully submit that this is not the capricious way in which he would operate. By the same token, you will not hear me express any disrespect for those who disagree.”

Advertisement

He is named People’s “Sexiest Man Alive.” He appears on late-night. His agenda is clear, and designed to strike anyone familiar with the rhetoric of the Christian right as sinister: “We must disarm, we must empower the United Nations, we must move to one currency, and we must become a global village.” He lays out the conditions under which he will accept appointment as secretary-general of the UN, and meets with the heads of the world religions to ask for resolutions supporting those conditions: a seven-year peace treaty with Israel, the relocation of UN headquarters to Iraq, where Babylon is to be rebuilt, and the establishment of a single world religion, headquartered in Italy, in exchange for which he will help the Jews of Israel rebuild their temple. “The man is brilliant,” Cameron Williams’s publisher announces. “Not only have I never seen someone with such revolutionary ideas, but I’ve also never seen anyone who moves so quickly.”

We understand immediately: this will be an end-times scenario with a political point. These are not books that illuminate Christian theology. The apocalyptic events of Revelation roll out in their appointed order, each judgment more literal than the last (another tenet in the Doctrinal Statement of the Pre-Trib Research Center affirms that “we believe the Bible should be interpreted normally, as with any other piece of sane literature, by a consistently literal hermeneutic which recognizes the clear usage of speech figures”), famine giving way to pestilence, fire to the falling star to the darkening of the sun by a third (“We’re going to have to determine what this means to all our solar-powered stuff” is Rayford Steele’s typically process-oriented response to this development), the plague of locusts to the plague of two hundred thousand brimstone-breathing horses to the plague of boils, the sea turning to blood, and, in Armageddon, the Euphrates drying up. What might seem to be the lesson of the Christian litany, that only through the acceptance of a profound mystery can one survive whatever spiritual tribulation these poetic fates are meant to signify, is not the lesson of the “Left Behind” books, in which the fates are literal rather than symbolic, and the action turns not on their mystery but on the ingenuity required to neutralize them: a surprising number of the series’ beleaguered band of Christians turn out to have been trained, conveniently, as pilots, computer hackers, document forgers, disguise experts, black marketeers, interceptors of signal intelligence, and medical trauma specialists.

They are radically suspicious of authority. Respect for the law translates, for them, into submission to the Antichrist. In lieu of the law they depend on old-fashioned know-how. They have competence. When Revelation 13 tells them that only those bearing the mark of the beast will be allowed to buy and sell goods (“And he causeth all…to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads, and that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name”), a young mother among them (the former Stanford student) knows instinctively how to set up and successfully operate, so that no Christian need buy or sell, a worldwide commodity cooperative based on barter. When the commodity trader’s husband and father need to know what the Antichrist is plotting, they have no problem insinuating themselves into his New Babylon command structure so as to keep his every move under wire surveillance. These are Christians who can always lay hands on a Gulfstream. These are Christians who can with a few keystrokes scramble the Antichrist’s transmissions. These are Christians with a Web site of their own that gets one billion hits a day. In many ways it is from this assumption of competence, of the ability to manage a hostile environment, that the series derives both its potency and its interest: this is a story that feeds on wish fulfillment, a dream of the unempowered, the kind of dream that can be put to political use, and can also entrap those who would use it.

2.

The question of this administration’s relationship to the Christian right has been frequently muddled, most deliberately, or opportunistically, by the administration itself. We have come to recognize the rhetorical signals the President sends to evangelicals, a constituency which, since its turn toward political action in the 1970s and with the encouragement of those Republicans who would use it, has itself become the party’s plague of brimstone-breathing horses. By the 1994 congressional elections, Christian conservatives cast two of every five Republican votes. By the time of the 2000 Republican convention, Christian conservatives achieved a platform unswervingly tailored to their agenda, including the removal of language that could be interpreted as pro-choice, the removal of language that could suggest approval of civil rights for homosexuals, and the removal of language that could be seen to favor any form of sex education other than the teaching of abstinence. “It was a one hundred percent victory,” Phyllis Schlafly of the Eagle Forum said of the completed platform.

Now as then, evangelical Web sites provide primers on influencing legislators and maximizing the Christian vote, as well as call-to-action discussions of inflammatory issues, for example whether Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore was right to defy a federal court order to remove his Ten Commandments monument from the state judicial building’s rotunda. “Christian rights are being challenged,” was the conclusion on the Ten Commandments question of a September edition of the LeftBehind.com Newsletter, which is e-mailed to followers of the series from leftbehind.com. To the same point, Focus on the Family’s site offered a “Ten Commandments Action Center,” where readers could “learn who to contact and what to say” in support of Judge Moore.

Donald Paul Hodel, who served first as secretary of energy and then as secretary of the interior during the Reagan administration, is now president of Focus on the Family, and in that capacity recently wrote to The Weekly Standard objecting to its favorable review of two books by the Protestant theologian D.G. Hart, who had suggested that the disinclination of American evangelicals to separate religious from public concerns was deleterious to both. “The fact is that without the hard work and votes of millions of Christians who have chosen not to be silent,” Hodel warned, “there would be no Republican majority in both houses of the US Congress, no Bush presidencies, few Republican governors, and a small handful of statehouses in Republican hands.”

We understand this. We recognize the political wisdom that in 1999 led George W. Bush to vet his candidacy by speaking at a private San Antonio meeting of the Council for National Policy, the Christian conservative “educational” organization created in 1981 by, among others (with the funding of Nelson Bunker Hunt, T. Cullen Davis, and William Cies), the Reverend Tim LaHaye, who had not yet gone on to launch the “Left Behind” books but was then an executive of the Moral Majority. We recognize the same wisdom in the decision of the White House in 2002 to send both White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales and Deputy Director of the White House Office of Public Liaison Timothy Goeglein to speak at another private meeting of the council (in fact all meetings of the council are private, although its membership roster has on occasion been obtained and posted on the Web), this one, which featured Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as a principal speaker, in Tyson’s Corner, Virginia.

“We’ll probably discuss some of the hot issues that are relevant today,” Steve Baldwin, the council’s executive director, told ABC News at the time of the Virginia meeting. “The Middle East… We’ll have a number of speakers from different perspectives. We’re not of all one like mind when it comes to what’s going on there.” The assurance here of “different perspectives” on the Middle East is in fact more delicate than it might seem, since in the mind of at least one member of the council, in fact one of its founders and its first president, Dr. LaHaye, “there are at least twenty reasons” to believe that this generation, after a sequence of events meant to take place in the Middle East and looking not entirely unlike the events now in play there, “will witness the end of history,” or “the end times.” Revelation 9, for example, tells us that “the four angels who are bound at the great river Euphrates…kept ready for this very hour and day and month and year” will be released to “kill a third of mankind.” Revelation 16 suggests that the drying up of the Euphrates will clear the way for the armies of the Antichrist to reach Israel, Megiddo, Armageddon, and their final battle with Christ—all events covered in Dr. LaHaye’s “Left Behind” books.

Discussion of “end times,” like news of the Rapture, no longer surprises us, at least those of us even occasionally exposed to Christian radio or television or Web sites. We recognize that many people who play powerful roles in our government would now be reluctant to disagree for the record with the proposition that an absolutely literal interpretation of the Bible, most visible now in the attempt to include “creation science” in the curriculums of American public schools, offers a reasonable alternative belief system. We accept without comment the information that Bible reading is part of the President’s daily schedule, along with study of Oswald Chambers’s daily devotional My Utmost for His Highest, and that Bible study sessions take up a certain percentage of the White House week. We understand that when the President spoke in his 2003 State of the Union address about the “power, wonder-working power, in the goodness and idealism and faith of the American people,” what he wanted to demonstrate, or his speechwriter Michael Gerson wanted to demonstrate, was a familiarity with the Baptist hymn “There Is Power in the Blood,” in which the congregation hits it hard on the line about the power, power, wonder working power, in the blood, in the blood, in the precious blood of the Lamb.

We recognize that when the President stood in February 2003 in Nashville before a backdrop reading “Advancing Christian Communications” and told the National Religious Broadcasters that America’s enemies “hate the thought of the fact” that “we can worship the Almighty God the way we see fit,” he could be confident, his frequent mentions over the months of “churches, synagogues, and mosques” notwithstanding, that there would be no confusion among the 2,700 representatives of evangelical Christian radio and television stations in the Opryland Hotel that day about which God the President himself saw fit to worship. We recognized, early after September 11, his persistent use of the word “crusade” for what it was, a construction designed to slip past merely nominal Christians (the ones who prefer the churches that might as well be country clubs) but carry a specific message to the evangelical.

We have grown accustomed to frequent assertions of the President’s own faith, often by way of explaining what might otherwise seem an eerie absence of prudent doubt. We have heard many times the story of how the not-yet president, then soon to begin his second term as governor of Texas, heard the pastor of the Highland Park United Methodist Church in Dallas deliver a sermon about the reluctance Moses felt when chosen by God to lead his people out of Egypt, experienced a “defining moment” from which he drew the conclusion, as he put it in A Charge to Keep, the campaign autobiography he began with Mickey Herskowitz and finished with Karen Hughes, that people are “starved for leadership,” and decided to run for president. “I believe God wants me to be president, but if that doesn’t happen, it’s OK,” he was reported to have told a group in Texas in 1999.

On the day of his inauguration, when he was asked by a Midland friend if he was at all anxious about assuming the presidency, he was reported to have answered in the same somewhat dissociated spirit: “No, I’m very much at peace,” he was quoted as having said. On the eve of the invasion of Iraq, Elisabeth Bumiller reported in The New York Times that his friends and advisers said that he had no doubts about the course he was pursuing. “While Iraq weighs on him heavily, they say, a president who sees the world as a biblical struggle of good versus evil has never expressed any misgivings, or personal vulnerabilities, about going to war against Saddam Hussein.”

This presidential character, we have learned, began to reveal itself in the mid-1980s, when, after the failure of several oil investment schemes, Bush turned what could have seemed at the time a noticeably short attention span on the early stages of his father’s campaign for the 1988 presidential election. “He tried a lot of different things,” the Republican consultant Mary Matalin would later say, by way of placing this focus deficit in the correct light, on a PBS Frontline documentary about the 2000 campaign. “A lot of people think that’s the better way, the preferable way to go through life…. He moves on. He learns and he moves on.” Freed in this case to move on by the sale of his nearly bankrupt Spectrum 7 fund to Harken Energy, which initially gave him $600,000 in Harken shares and a consultancy fee of $120,000 a year (“I realize the value of your perspective in these matters and in particular, the tremendous value associated with my being able to ‘council’ with you from time-to-time,” the president of Harken wrote to the son of the president of the United States at the time this initial deal was sweetened), the younger Bush was assigned by his father to work with Doug Wead, who acted as the 1988 campaign’s liaison to the Christian right. Wead was himself an Assembly of God evangelist and a “motivational speaker” for Amway, the company accused at one point of encouraging the false but virtually ineradicable rumor that the Proctor & Gamble trademark was meant to represent the “666” identified in Revelation 13 as “the number of the beast.” During the younger Bush’s 2000 campaign, Wead was asked, on the same Frontline, if the candidate understood that some Americans reacted warily to open declarations of faith. “He’s keen to that,” Wead said.

But unlike some, he also knows the numbers, he knows how important faith is to millions of people in the United States. Ninety-five percent believe in a personal god in the United States. It’s a very high number…. Every subculture has its own language and its own inflection. Even, sometimes, it’s the emphasis of a syllable in a word, or you could have one word out of order, and instantly you recognize someone from your own subculture. And the evangelical subculture is no different. When G.W. meets with evangelical Christians, they know within minutes that he’s one of theirs. Now, most presidential candidates, they have to probe, and they have to look, try to find common denominators that they can say, “Well, he’s kind of ours, he just doesn’t know it”; or, “He’s ours but he doesn’t understand the culture.” And with G.W., they knew it was real. I don’t know how to explain that without defining the whole subculture itself, which you can’t do in 30-second answers. But they knew it.

In another interview, conducted by Hanna Rosin of The Washington Post, Wead explained the passwords to the subculture in somewhat more detail. He described how, during the 1988 campaign, when evangelists would ask “their usual trick questions,” for example what argument the candidate would give the Lord to gain entry through the gates of heaven, the senior Bush, the Episcopalian, would give “the classic wrong answer, something like ‘I’ve been a good man and I’ve done my best.'” The “right” answer, according to Wead, would have been “something like ‘I know we’re all sinners, but I’ve accepted Jesus Christ as my personal savior.'” The younger Bush, on the other hand, could see such questions “coming from a mile away” and effortlessly give a correct response, such as “I know what it means to be right with God,” then, just as effortlessly, segue into flattering his interrogator.

Campaigning for himself in 2000, the son spoke frequently of the “mustard seed” of faith, sometimes abbreviated to the “seed,” which he believed to have been planted in his soul by the Reverend Billy Graham in the course of a walk on the beach at Kennebunkport during the summer of 1985. “I recognize I’m a humble—I’m a lowly sinner who sought redemption,” he told Bill O’Reilly on Fox-TV during the 2000 campaign. Once in possession of the Oval Office, according to David Frum’s The Right Man: The Surprise Presidency of George W. Bush, he gave a group of visiting clergymen the more result-focused, but equally familiar, reading of his conversion: “You know, I had a drinking problem. Right now I should be in a bar in Texas, not the Oval Office. There is only one reason that I am in the Oval Office and not in a bar. I found faith. I found God. I am here because of the power of prayer.”

We were told so repeatedly about this conversion and its reward, the elevation from the bar to the Oval Office, that we came to accept it in its broad-stroke version, a cartoon of amazing grace (he once was lost but now is found), the kind of “story,” or “qualification,” heard many times a day at twelve-step meetings in church basements all over America. We were told, again in the twelve-step tradition, exactly how mean a drunk he had been. According to Christopher Andersen’s George and Laura: Portrait of an American Marriage, he once in a Mexican restaurant in Dallas launched a rabid attack on Al Hunt, the Washington bureau chief of The Wall Street Journal, colliding with other diners as he made his way to the table where Hunt was sitting with his wife, the television correspondent Judy Woodruff, and their four-year-old son. When he reached the Hunts, “red-faced” and “clearly intoxicated,” he pointed a finger and began shouting.

“You no good fucking son of a bitch!” George W. screamed while other diners looked on in shock. “I will never fucking forget what you wrote!” For the next minute or so, W. stayed at the table, continuing his diatribe against the story [a story about the 1988 campaign in which Hunt had been quoted] in the Washingtonian. But Hunt could not imagine what could have provoked such rage. He had not even mentioned the elder Bush in the Washingtonian article, much less criticized him. With that, W. weaved his way through the restaurant and out to the parking lot.

Again according to Andersen, Bush’s only response to a late-night kitchen-table ultimatum from his own wife (“either their marriage or the bottle”) was to study her for a beat, get up, walk over to the kitchen counter, and pour himself another bourbon.

Both these incidents took place in 1986. We do not ask why, if the mustard seed got planted during the walk on the beach in the summer of 1985, the same summer the sinner joined a men’s Bible study group in Midland, he appeared to exhibit no inclination to let faith extend its wonder-working power to his disposition until the following summer, the famous birthday party at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs where everyone ended up too hung over to visit the Air Force Academy Chapel and the President’s son quit drinking. Nor do we dwell unnecessarily on the fortuitous way in which the sinner found God at the exact moment when he was called upon to corral the religious right into his father’s camp.

There is a reason we do not dwell on such points, and the reason is this: the question they raise, that of “sincerity,” makes no substantive difference. Either of the two possible answers to the question—the politician who talks the talk of the true believers is himself a believer, or the politician is merely an astute operator of the electoral process—will produce, for the rest of us, the same end result. In either case, believer or operator, the politician will be called upon to display the same stubborn certainty on any issue presented to him. In either case, committed fundamentalist Christian or pursuer of the fundamentalist Christian vote, the politician will be called upon to consign the country to the same absolutist scenarios. “We have carried the fight to the enemy,” the President declared in his September 7 address to the nation. “We are rolling back the terrorist threat to civilization, not on the fringes of its influence, but at the heart of its power…. We will do what is necessary, we will spend what is necessary, to achieve this essential victory in the war on terror, to promote freedom, and to make our own nation more secure.”

We understand: the perfect beauty of the fundamentalist redemption story as applied to the public arena is that it transfers responsibility for any chosen mission from the believer in that mission to the nonbeliever (as in, from the same speech, “Members of the United Nations now have an opportunity, and the responsibility, to assume a broader role in assuring that Iraq becomes a free and democratic nation”), transforms even the most calculated political play into a reward for faith, conveniently serves as the last word on any errors that might surface.

3.

There are obvious problems, made manifest over the past two years, in letting this kind of personality loose on the fragile web of unseen alliances and unspoken enmities that constitutes any powerful nation’s map of the world. The fundamentalist approach to information, whether that approach is innate or learned, does not encourage nuanced judgments. Bill Keller, in The New York Times Magazine, reminded us that “Bush bonded with Vladimir Putin over the Russian’s story of a lost crucifix.” (“I was able to get a sense of his soul,” Bush himself said after his first ninety-minute meeting with Putin.) Nicholas Kristof reminded us in the Times that Bush has said he does not believe in evolution. “After all, religion has been around a lot longer than Darwinism,” Bush told George magazine on this point. In a July 2003 fund-raising letter sent out over the President’s name, after the usual stealth promises to redirect government money to the private sector (“My goal is to build an ownership society where American families own their own homes, their own health coverage, their own retirement accounts and, if they want, their own businesses”), recipients could find this unsettling confidence: “One of the paintings I selected for the Oval Office portrays a man on horseback, leading a charge up a steep hill. His face is full of purpose and determination, and it is clear he expects to get the job done. The painting is called ‘A Charge to Keep,’ based on a Methodist hymn that’s a favorite of mine, ‘A Charge to Keep I Have.'”

George W. Bush is by no means the first American president to see himself leading a charge uphill, nor are those around him the first to seize the opportunity, in another phrase from the same fund-raising letter, to “make use of the moment history has given us to extend liberty to others around the world.” President William McKinley occupied the Philippines on the strength of a putative need to extend enlightenment throughout the archipelago. The New York Globe in 1847 urged the annexation of Mexico because “it would almost seem” that its citizens “had brought upon themselves the vengeance of the Almighty, and we ourselves had been raised up to overthrow AND UTTERLY DESTROY THEM as a separate and distinct nation.” What seemed novel in Bush was the dispatch with which he claimed for himself the personal guidance of God. At a meeting with his national security advisers on the evening of September 11, 2001, according to Bob Woodward’s Bush at War, he was already describing the attacks as “a great opportunity.” By the afternoon of September 12, again according to Woodward, he was describing himself to Bernadine Healy of the American Red Cross as “in the Lord’s hands.”

This notion of the nation, or its president, having been chosen to fulfill some divine purpose was repeated many times, with the active encouragement of the White House. Within days of the September 11 attacks, White House aides were confiding to Time that the President was “privately” speaking of having been “chosen by the grace of God to lead at that moment.” “I think President Bush is God’s man at this hour,” Timothy Goeglein of the White House Office of Public Liaison told the Christian weekly World, “and I say this with a great sense of humility.” The President was presented as accepting his mission with an equal sense of humility: after his address to Congress on September 20, 2001, according to Deborah Caldwell, a producer at Beliefnet.com, he received a call from his speechwriter, Michael Gerson. “Mr. President, when I saw you on television, I thought—God wanted you there,” Michael Gerson is supposed to have said. “He wants us all here, Gerson,” the President is supposed to have said in response.

One political danger in linking the legitimacy of a presidency to divine will, supposedly expressed at a single moment in history—in this case the “great opportunity,” or “the moment history has given us to extend liberty to others around the world”—is that the authorizing moment, however potent a place it occupies in the national imagination, eventually passes. That even the awesome clarity of September 11 should have become clouded was due principally to the administration’s overuse of it. During the six weeks prior to the second anniversary of the attacks, Mike Allen of The Washington Post reported, the President mentioned September 11 in reference not only to Iraq and Afghanistan and airport security, but also to his energy policy, his tax cuts, unemployment, the deficit, and campaign fund-raising. When asked in July about the $170 million budget for his unopposed 2004 primary campaign, Bush responded, according to Allen, with this retreat to what he clearly considered his unique selling proposition: “Every day, I’m reminded about what 9/11 means to America.” The nation was, he explained, “still threatened,” making it necessary for him to “continue doing my job, and my job will be to work to make America more secure.”

This use of September 11 as the irrefutable answer to any political argument, a strategy adopted within days of the attacks, began to seem increasingly doubtful. There came a point when it became difficult not to suspect that the package of urgent and in many cases unrelated revisions made to carry the imprimatur of September 11—the Patriot Act, the tax cuts, the scaling back of environmental and workplace protections—had done little to secure our nation and much to dismantle our protections as citizens. We were receiving daily reports that the forces against which we had fought in Afghanistan were regaining the initiative, preparing to wage against us the same war of attrition they had successfully pursued in the 1980s, with our support, against the Soviets. We were simultaneously receiving regular assurances from the President, for example in his September 13, 2003, radio address, that in Afghanistan we had “removed the Taliban regime that harbored al-Qaeda.” As the crisis of the initial attacks extended first into prolonged military deployments and then into what Condoleezza Rice and The Weekly Standard would begin calling a “generational commitment,” it became increasingly difficult to banish concern that the true gravity of our situation was being systematically put to the service of political ends.

That such concern would arise might have seemed predictable enough. Curiously, given that predictability, the administration seemed not just unwilling but entirely unprepared to address its critics, returning instead to its insistence on divine intervention, which was increasingly offered as a reason for waging war that could stand on its own. Since God was on America’s side, there need be no further reason to discuss the presence or absence of weapons of mass destruction. Since we were acting out divine will, we could regard as moot any question of whether we had succeeded mainly in further encouraging those who would act against us. In his January State of the Union address, the President had spoken of how the nation, still unable to extricate itself from Afghanistan and then facing Iraq, could trust in “Providence,” place its confidence in “the loving God behind all of life, and all of history.” The “sacrifice” we would make “for the liberty of strangers,” he said, was “not America’s gift to the world,” but “God’s gift to humanity.”

In February, addressing the Religious Broadcasters in Nashville, the President had repeated this conflation of the administration’s policy with “God’s gift to every human being in the world,” and spoken of how America had been “called” to lead the world to peace. The next day, during the noon press briefing at the White House, Ari Fleischer was asked these questions:

Q: Ari, you’ve just touched on the fact that the President has mentioned his faith in a number of recent speeches, what should the perception be in a Muslim world where clerics have recently framed this as a religious or holy war, spoken about the fangs of our enemy? That’s my first of two questions on this subject.

A: Well, I think the lesson is that America has been a shining example to the world of how people of a variety of faiths can find strength in tolerance and strength in faith and respect for people of whatever faith and people who have no faith. That’s been the wonderful American example to all the world. And that’s the message that the President believes strongly in. And he hopes it’s a message that spreads around the world.

Q: Given foreign perceptions and domestic—traditional domestic concerns about separation of church and state, is the President comfortable when he’s introduced as he was yesterday, as our brother in Christ?

A: He is. And at the meeting the President had prior to the introduction, he was joined by people from a variety of faiths. There was a rabbi with him.

There is a second danger, not unrelated to the first, in so firmly linking the authority of the presidency to divine will. That this president was elected in 2000, however narrowly, was due only in part to the support of the Christian right, a constituency which wields its true strength on a candidate’s behalf mainly during the primary process, when fewer people vote and the energized support of one or another bloc can decisively influence the party in its choice of a candidate for the November general election. Those who turn out for the general election vote a different agenda, which, as time passes, they may or may not believe to be receiving the attention due it from the administration. The agenda that elected George W. Bush in November 2000 was not in every venue stated directly but was clear to his heavier-hitting supporters, based as it was on their wish to get government regulators out of their hair and the IRS out of their profits.

This was the constituency, as it watched the political capital for its agenda draining away into the Middle East, that first showed signs of restlessness. During the late fall of 2002, in the course of traveling around the country as it waited for war in Iraq, Peter King of the Los Angeles Times spent a morning at the Petroleum Club in Midland, where eight or nine oil men, each of whom knew the President in one or another way, sat around a poker table and talked. “What bothers me,” one said, “is that it’s a never-ending situation in the Middle East.” He continued:

It’s kind of like stirring up those damn fire ants. They go underground for a while and then they come back and eat you up. And I’ve got a lot of mixed feelings about where we might be at the end of it. Who will be next after Iraq? How much will it cost to rebuild the country? And how will we pay for that?… As far as I’m concerned, the case has not been made. It’s probably been made to the people in charge. I don’t know all what they know. I can only go by what’s on the table…. I’d kind of like to see the economy in better shape before we take on more spending. Afghanistan is already turning out to be a bleeder. Iraq will be a bleeder too.

This interview at the Petroleum Club in Midland took place in November of 2002, some months before hostilities began in Iraq. By September of 2003, some months after major hostilities were declared finished (“MISSION ACCOMPLISHED” was the banner on the carrier where the President staged his victorious landing), the number of Americans who said they believed the war to be worth fighting had dropped, according to an ABC News poll, to 54 percent, down from 70 percent in April. The same month, at a Bush fund-raiser in Jacksonville, Florida, a Republican real estate investor talked about the situation to The Washington Post. “This aftermath in Iraq is going to be tougher than we thought it was,” the investor said. “I am very worried about it,” a Republican job recruiter in Omaha told The New York Times, also in September. “I have two brothers in the Navy. I think there are going to be a lot more casualties. I think we are in there for the long haul. I believe we did the right thing. But I don’t see a winning situation here for anybody.” The Republican mayor of Xenia, Ohio, a town near Dayton with a population of 24,000, talked to the Los Angeles Times, again in September, about the President’s reelection prospects: “If things don’t improve it could be a disaster for him,” the mayor said. “What’s bothering people is they believe they are losing jobs because of the war. We’re a manufacturing state. The recession is hurting. That’s causing people to ask questions.”

This was now the voice of what used to be the Republican Party, but it was not the voice of what increasingly seemed the President’s preferred constituency, those who could feel secure about whatever destructive events played out in the Middle East because those events were foreordained, necessary to the completion of God’s plan, laid out in prophecy, written in the books of Genesis and Jeremiah and Zechariah and Daniel and Ezekiel and Matthew and Revelation, dramatized in the fifty-five million copies of the “Left Behind” books, amplified in countless hours of programming on Christian radio and television, and would ultimately lead, after the dust settled, to the Glorious Appearing and Thousand-Year Reign of Jesus Christ.

“It seems as if he is on an agenda from God,” one of the religious broadcasters who heard the President speak in Nashville in February had said to Dana Milbank of The Washington Post. “The Scriptures say God is the one who appoints leaders. If he truly knows God, that would give him a special anointing.” Another had agreed: “At certain times, at certain hours in our country, God has had a certain man to hear His testimony.” President Bush, the Post article had concluded, drawing in elements of the familiar fundamentalist redemption story and melding them with the dreams of the administration’s ideologues about remaking the entire Middle East, “admires leaders who have overcome adversity by finding their life’s mission, much as he has gone from drinking too much to building a new world architecture.” We have now reached a point when even the White House may be forced to sort out how a president who got elected to execute a straightforward business agenda managed to sandbag himself with the coinciding fantasies of the ideologues in the Christian fundamentalist ministries and those in his own administration.

—October 9, 2003

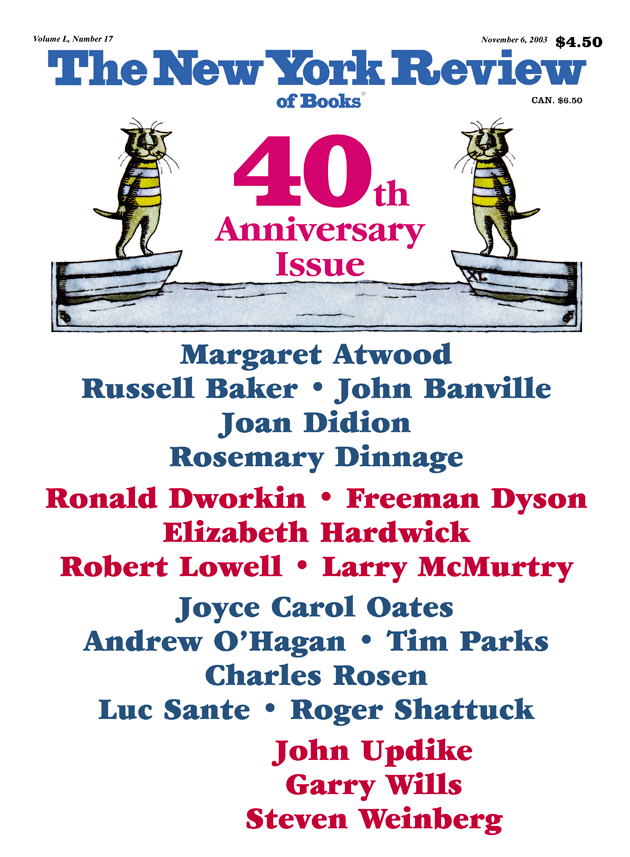

This Issue

November 6, 2003