To the Editors:

In your February 26 issue, Michael Massing [“Iraq: Now They Tell Us”] attempts to take the media to task for its pre-war coverage of the WMD issue. Mr. Massing asserts that the media was aware of specialists within the government and among the expert community who challenged the Bush administration’s allegations on Iraq’s purported programs to develop nuclear, biological, and chemical arms but chose not to report dissenting views.

In making this argument Mr. Massing leaves out references to my work that do not fit his thesis. He also provides an incomplete account of the views of the expert community. In short, Mr. Massing commits the very sins for which the critics have taken the Bush administration to task: to bolster his case he has cherry-picked the evidence.

The issue of WMD is complex and more complicated than Mr. Massing suggests. It was possible, for example, to challenge the CIA’s claim that Iraq had sought to purchase aluminum tubes to produce enriched uranium and still hold the view that Saddam Hussein was probably trying to reconstitute his nuclear weapons program, had stockpiles of poison gas, and had an active germ weapons program.

That, as we now know, was the view of the Energy Department, according to the declassified National Intelligence Estimate of October 2002. It was the position British intelligence took in its September 24 White Paper on “Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction,” the document that British Prime Minister Tony Blair used to persuade his nation to go to war.

David Albright, a knowledgeable and honorable former weapon inspector on whom Mr. Massing relies for much of his critique, held a similar view. Mr. Albright argued that the Bush administration did not have a firm basis for asserting that the tubes were suitable only for making centrifuges to enrich uranium. At the same time, he and a colleague published a paper that suggested that new activity at al-Qaim in western Iraq might be part of a secret Iraqi effort to make a nuclear bomb. The paper was published on September 12, 2002, four days after the Times article on the tubes appeared, and is still on his Web site. In other words, Mr. Albright was concerned that Iraq might be moving to regenerate its nuclear weapons program but held that tubes were likely not part of that effort.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a respected organization whose work Mr. Massing cites approvingly, noted in Deadly Arsenals, its survey of world proliferation issues, which was published in the summer of 2002, that there was “heightened anxiety” concerning the possibility that Iraq was involved in a covert nuclear program and added that Iraq could well have stocks of germ weapons and poison gas.

I stand by my assertion to Mr. Massing that the notion that Iraq had some form of WMD was a widely shared assumption inside and outside of the government. I made that comment not to excuse any limitations on the part of the media but to paint the context in which American intelligence was prepared and discussed. Mr. Massing takes that assertion out of context, and he cites Mr. Albright’s work to challenge that observation though his work actually supports it.

Nonetheless, the aluminum tubes figured prominently in the debate. In a September 8, 2002, article, which I coauthored, I reported the view of the CIA and a majority of the intelligence community that the tubes were being sought by the Iraqis to make centrifuges to enrich uranium as part of a nuclear weapons program. In the fall and winter of 2002 I was in Kuwait, Israel, Qatar, Bahrain, Djibouti, and Turkey, among other locations, in my role as a military reporter.

In the meantime, the debate over Iraqi WMD continued to evolve. By January, weapons monitors had returned to Iraq and begun to conduct their first inspections since 1998, which was an important development. Dr. Mohamed ElBaradei, the director general of the IAEA, was preparing to deliver his assessment to the United Nations Security Council. It was clear that the initial claims made to me by some administration officials (and which I noted in a September 13 article) that the debate over the tubes was simply a technical dispute between the CIA and the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research were no longer plausible.

I reported the IAEA’s assessment in a January 10 article, which bears the headline “Agency Challenges Evidence Against Iraq Cited by Bush.” The IAEA’s dissent was strong, though not unqualified. That article noted other dissenting views by the State Department, the Energy Department, and British intelligence. It quoted Gary Samore, an expert at the International Institute of Strategic Studies and the senior proliferation official on President Clinton’s National Security Council, as saying that the IAEA presentation had weakened the Bush administration’s argument that Iraq was trying to revive its gas centrifuge program for making bomb-grade materials. Mr. Massing briefly alludes to that article but only to complain that it ran inside the paper. Strangely, he does not mention that I wrote it.

Advertisement

I have gone back to see what other coverage the Times had that day about Dr. ElBaradei’s presentation. It was a day in which Hans Blix, the chief UN weapons inspector, also appeared before the Security Council to provide his assessment that Iraq had failed to provide sufficient information to dispel concerns over its weapons activities. The front-page article by our UN correspondent reported both presentations and took note of Dr. ElBaradei’s position on the tubes. The Times also included a text sidebar, which provided excerpts from Dr. ElBaradei’s formal presentation. The purpose of my article was to provide additional information to supplement the front-page article and the ElBaradei text.

On January 27, Mr. Blix and Dr. ElBaradei returned to the United Nations to provide their updates following their visit to Iraq. These were much-awaited presentations. Again, our UN correspondent covered each of the assessments, including Dr. ElBaradei’s report that his inspectors had detected no sign of nuclear activities in Iraq and his assertion that the presence of inspectors in Iraq would serve as a deterrent to the resumption of a nuclear program. As part of our coverage that day, I coauthored a January 28 article with James Risen, the Times intelligence reporter, which bears the headline “Findings of UN Group Undercut US Assertion.” The article outlined the IAEA case and explained what inspections the agency had conducted in Iraq. This article is not mentioned in Mr. Massing’s account.

For the record, there were several other stories in which I and other Times correspondents noted positions that challenged the Bush administration’s case. In a front-page article on November 10, I recounted the CIA’s assessment that Iraq was unlikely to cooperate with terrorists who sought to attack the United States. Specifically, I wrote that an assessment conveyed to Congress in a letter by CIA Director George J. Tenet and other intelligence reports “do not support the White House’s view that Iraq presents an immediate threat to the American homeland and may use Al Qaeda to carry out attacks at any moment.”

Mr. Massing mentions this article briefly and in passing but does not seem to appreciate the significance of this issue. The Bush administration case for preemptive war turned not only on allegations that Iraq had WMD but also on the assertion that it would give such weapons to terrorists. The CIA assessment of the absence of a terrorist link is contained in the same National Intelligence Estimate that makes the case on the aluminum tubes, which shows just how complex the issue of pre-war intelligence can be.

This was hardly the only time the Times cited evidence that challenged this administration’s efforts to draw a link between Iraq and al-Qaeda. Mr. Risen’s front-page October 20 story from Prague, which Mr. Massing does not mention, is another example.

An important question is why the testimony by Dr. ElBaradei did not have more influence on the public debate in the United States. It may have been because of public attitudes toward international organizations. The public may have discounted Dr. ElBaradei’s testimony because the IAEA grossly underestimated Iraq’s nuclear efforts before the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Secretary Powell’s skills at persuasion may have been a factor.

Another reason Dr. ElBaradei’s views did not have more influence, I believe, was that he presented his assessment in tandem with Mr. Blix and Mr. Blix generally delivered negative reports about Iraqi cooperation with weapons inspection efforts. On January 27, for example, Mr. Blix told the Security Council that “Iraq appears not to have come to genuine acceptance—not even today—of the disarmament which was demanded of it and which it needs to carry out to win the confidence of the world and live in peace.” He then outlined a list of ways in which Iraq had failed to dispel concerns about its weapons activities. That was a dramatic assertion and made headlines. It was made the same day that Dr. ElBaradei repeated his verdict on the aluminum tubes.

While the main focus of Mr. Massing’s critique is about intelligence about Iraq’s nuclear program, and the nuclear allegations were a key element of the Bush administration’s case, it is worth recalling that Iraq’s suspected biological weapons program was also cause for concern. The CIA held, as the Times and most of the major media reported, that Iraq was five to seven years away from making a nuclear weapon if it produced the fissile material itself and less than a year away from a bomb if it succeeded in buying the material on the black market. But germ weapons, if they existed, would have presented a current danger. In his January 27 assessment, Mr. Blix warned there were “strong indications” Iraq had made more anthrax than it declared, and “at least some of this was retained after the declared destruction date.” When the Iraqis sent a letter asserting their germ weapons had been destroyed Mr. Blix responded that this was not evidence.

Advertisement

Since the war, Mr. Blix has theorized that Saddam’s greatest deception may have been to maintain a sense of ambiguity over the status of his weapons programs even after Iraq had disposed of its stocks. As Mr. Blix has put it, “You can put a sign on your door, ‘Beware of Dog,’ without having a dog.” That is an intriguing theory about how Saddam may have hoped to use the threat of WMD to maintain control at home and deter attacks from his foreign adversaries while cooperating just enough to stave off a United Nations Security Council vote authorizing military action. But it was not an assessment I heard Mr. Blix make before the war.

After the war, the Carnegie Endowment prepared a lengthy January 2004 report, which concluded that Iraq’s nuclear program had been dismantled by inspectors after 1991 and could not have been resumed without detection. Mr. Massing cites this report to suggest that the absence of an Iraqi nuclear program should have been apparent to the media in the fall of 2002, which was when the CIA’s new nuclear allegations were being reported. The Carnegie report, however, makes no such assertion. Joseph Cirincione, a senior associate at Carnegie and one of the authors of that document, recently told me that his view is that the absence of an Iraqi nuclear program could have been discerned “in the months after the inspectors came back, not in the fall of 2002.” That is an important distinction to keep in mind in assessing the media’s performance.

This is not to say that the press coverage of the WMD does not warrant fair-minded scrutiny. Sometimes the media is confronted by officials who seek to deceive the press. But the WMD issue was more complicated. In this instance, key officials appear to have deceived themselves. That poses special challenges for reporters but one which journalists should be prepared to meet. There is a lesson for the media in this episode. It is possible to be too accepting of the paradigm that guides the intelligence community, nongovernmental experts, and policy officials.

Those who also want to examine the record and judge for themselves can find the declassified NIE, the British White Paper, and other relevant documents on the Carnegie Endowment’s Web site (www .ceip.org). I also recommend an insightful article on pre-war intelligence which appeared in the January/February 2004 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. It was written by Kenneth M. Pollack, a former CIA official and NSC aide, who supported the case for military intervention.

Michael Gordon

The New York Times

Washington, D.C.

To the Editors:

Michael Massing, in his March 25 response to Bob Kaiser’s letter defending the Post’s coverage of the pre-war Iraq intelligence, states that “the discussion should focus solely on the journalistic record.” Perfectly sensible. So why, in the same response, does Massing say he didn’t make mention of an article I wrote—an article that firmly contradicts Massing’s thesis—because I “never responded” to his phone calls? For the record, Massing called the week my first child was born. But why doesn’t the “journalistic record” speak for itself when it runs counter to Massing’s views?

Dana Milbank

The Washington Post

Washington, D.C.

Michael Massing replies:

In retrospect, the September 8, 2002, article by Michael Gordon and Judith Miller about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction seems one of the most serious cases of misreporting in the entire run-up to the war. The piece provided a major boost to the administration’s case for war—and proved to be wrong in almost every detail. Rather than own up to this and ponder what went wrong, Gordon offers excuses and rationalizations.

As my article noted, while most observers believed that Iraq had biological and chemical weapons, there was much doubt about the state of its nuclear program. It was the prospect of Saddam Hussein’s getting an atomic bomb that caused the most fear about his regime, and it was this fear that the Bush administration most sought to fan as it pushed the case for war. Yet it had little concrete evidence to show that Iraq was actively seeking a bomb.

Enter The New York Times. In that September 8 story, Gordon and Miller, leaning heavily on Bush officials, offered the aluminum tubes as evidence that Iraq was actively seeking a nuclear weapon. The article did not simply raise this as a possibility—it asserted it in bold and unequivocal language. “US Says Hussein Intensifies Quest for A-Bomb Parts” ran the headline. Iraq, the lead declared, “has stepped up its quest for nuclear weapons and has embarked on a worldwide hunt for materials to make an atomic bomb, Bush administration officials said today.”

As my piece related, the Times story raised serious doubts among many nuclear experts, including David Albright. As I noted, Albright and his think tank, the Institute for Science and International Security, favored tough action on Iraq, believing that the regime had WMD and so had to be contained through constant vigilance. But Albright also believed that the case against Iraq, to be credible, had to rest on accurate information, and, having looked into the matter of the tubes, he knew that many specialists doubted the assertions the Times piece made about them. Trying to alert the paper, Albright had several long conversations with Judith Miller, patiently explaining to her the skepticism many experts felt. Yet the resulting story, appearing on September 13 and written by Miller and Gordon, contained only a brief and dismissive reference to these experts’ views. My article described Albright’s dismay over this, quoting him as saying that the Times “made a decision to ice out the critics and insult them on top of it.”

Anybody doubting my account of this can check Albright’s own report, “Iraq’s Aluminum Tubes: Separating Fact and Fiction,” available at www.isis-online.org. In it, Albright writes that the Times’s September 13 story “was heavily slanted to the CIA’s position, and the views of the other side were trivialized.” In the story, he added,

an administration official was quoted as saying that “the best” technical experts and nuclear scientists at laboratories like Oak Ridge supported the CIA assessment. These inaccuracies made their way into the story despite several discussions that I had with Miller on the day before the story appeared—some well into the night. In the end, nobody was quoted questioning the CIA’s position, as I would have expected.

Albright goes on to note that he “wrote a series of ISIS reports criticizing the administration’s claims about the tubes and its misuse of information to build a case for war,” and that these became the basis for an article in The Washington Post on September 19, 2002, that disclosed the doubts some experts had about the tubes’ suitability for use in centrifuges.

As Albright goes on to note, the Times’s September 13 article, by carrying the categorical dismissal by senior officials of the dissenters’ views, made those dissenters nervous about discussing the issue further. By contrast, reporters at Knight Ridder Newspapers, after writing about the dissent in the intelligence community, began receiving calls from sources eager to talk. Thus, the Times’s heavy reliance on official sources and its dismissal of other sources may have discouraged potential dissenters from discussing their views with its reporters; in any case, as I showed, the paper neglected an important segment of analyst opinion.

Gordon mentions the National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq. The declassified version of this document offered a recitation of the intelligence community’s official claims about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. The one discordant note concerned the aluminum tubes. While noting that the intelligence community as a whole believed the tubes were intended for use in centrifuges, the document acknowledged that some experts disagreed, believing the tubes were intended for use in conventional weapons. Gordon, who wrote a story for the Times on the NIE, made only the briefest mention of this dissent; for the most part, his piece was a stenographic-like summary of the NIE’s findings.

By contrast, Knight Ridder’s Jonathan Landay, noting the document’s unusual reference to a dissenting view, decided to investigate further, and he eventually reached a veteran of the US uranium enrichment program who told him that the data on the tubes were far from conclusive. As my article recounted, Landay went on to write an article about how the CIA report “had exposed a sharp dispute among US intelligence experts” over the state of Iraq’s arsenal. The contrast between the two accounts is striking.

Gordon refers to a front-page story he wrote about how the CIA’s assessment that Iraq was unlikely to cooperate with terrorists did not support the White House’s view about the immediacy of the Iraqi threat. (Oddly, Gordon gets the date of this piece wrong—it appeared on October 10, not November 10, 2002.) I found this article highly informative and so mentioned it in my piece. Alas, this was not enough for Gordon, who believes I should have given it more attention. But as my article noted, this piece was only one of a number to appear in the Times and other papers in this period offering an independent assessment of the administration’s statements about the Iraqi threat. It was the sudden silence that set in in late October and that lasted until the start of the war that I found so troubling, and that I discussed at length in my article.

(Dana Milbank seems to have misunderstood this. If he will look again at my comment in the March 25 issue he will see that I described his article as one of the group of critical stories that appeared in October. I had to select which of these to cite. Without being able to reach Milbank and learn more about the reaction to his story, I decided to go with some of the others.)

Gordon cites as evidence of the Times’s (and his) independence in these months two articles that he wrote or co-wrote in January 2003, both on statements issued by Mohamed ElBaradei of the IAEA. ElBaradei’s reports were profoundly significant, offering the most definitive account of the state of Iraq’s nuclear program after the departure of UN inspectors in 1998. From 1991 to 1998, those inspectors had by all accounts dismantled Iraq’s nuclear program. And, citing the Carnegie Endowment report, I observed that it would have been “very difficult” for Iraq to conceal from the outside world any effort to resume that program. It’s these facts that I said were “largely knowable” in the fall of 2002, not (as Gordon asserts) whether Iraq had actually resumed its nuclear program. That was knowable only after the inspectors returned to Iraq, in late November 2002. And it was precisely this issue that ElBaradei addressed in his two reports in January. After weeks of inspections, he stated, the IAEA had found no evidence of any ongoing nuclear activities in Iraq. And, he added, after extensive investigation, the agency had determined that the aluminum tubes were more likely intended for use in conventional rockets than in centrifuges.

So, on the critical issue of whether Iraq was actively seeking a nuclear bomb, the IAEA had found strong indications that it was not. And how did the Times cover these key statements? With two short, pro forma stories buried inside the A section. Contrast this (as I did in my article) with the long, front-page account by Joby Warrick in The Washington Post, which complemented the IAEA findings with interviews with weapons inspectors, scientists, and other experts to point out weaknesses in the administration’s case about the aluminum tubes.

As to why the ElBaradei reports did not have more impact, Gordon speculates that the “public” may have discounted his testimony because the IAEA had “grossly underestimated” Iraq’s nuclear efforts before the 1991 Gulf War. He also cites Colin Powell’s “skills at persuasion.” This is unconvincing. First, I doubt that the “public” had any recollection whatever of the IAEA’s activities in Iraq prior to the 1991 Gulf War. Far more important in shaping the public’s views were the statements put out by the administration and carried uncritically in the press. If the Times and other news organizations had given ElBaradei’s statements more attention, the public no doubt would have, too.

Gordon’s allusion to Colin Powell’s persuasiveness is particularly interesting in light of all the questions that have been raised about his February 5, 2003, speech to the United Nations. The Times ran three front-page stories on that speech, one by Michael Gordon. While questioning some of Powell’s assertions about Iraq’s links to terrorists, Gordon offered unqualified praise for his assertions about Iraq’s WMD. “The case Mr. Powell presented today regarding Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction” was “remorseless,” Gordon wrote. “Even the skeptics,” he added,

had to concede that Mr. Powell’s presentation had been an important milestone in the debate. Critics may try to challenge the strength of the administration’s case and they will no doubt argue that inspectors be given more time. But it will [be] difficult for the skeptics to argue that Washington’s case against Iraq is based on groundless suspicions and not intelligence information.

On the nuclear issue, Gordon wrote, Powell “presented new details to buttress the administration’s case”; in particular, he cited Powell’s claim that the United States “has intercepted aluminum tubes that had a special coating that would make them useful for making centrifuges to enrich uranium.” Remarkably, Gordon did not see fit to mention the IAEA findings that undermined this claim and that he, Gordon, had twice written about in the previous month. So, at this key juncture in the debate on Iraq, Gordon uncritically transmitted a key US claim, one that the inspectors had effectively discredited. In the light of such reporting, is it any surprise that the IAEA findings had such limited impact?

Gordon’s ruminations about why Hans Blix’s statements received more attention than Mohamed ElBaradei’s conveniently overlook any possible part the press may have had in this. A passage from Blix’s new book Disarming Iraq is worth quoting in this regard:

While nuclear weapons are routinely lumped together with biological and chemical in the omnibus expression “weapons of mass destruction,” it is obvious that they are in a class by themselves. The outside world’s concerns about Iraq’s weapons would never have been a very big issue if it had not been for Iraqi initiatives to acquire nuclear weapon capacity, and for the level of success it had attained by 1990 in enriching uranium. It is the more disturbing, then, that categorical and key contentions about continued Iraqi nuclear efforts and attainments, made at the highest levels of the US and UK governments from 2002 on, were simply wrong, and could have been avoided with a moderate dose of prudence.

And, he might have added, with more critical scrutiny from the press. The US press’s intense focus on the Blix reports and its corresponding neglect of the ones by ElBaradei are, I believe, yet another illustration of the pack mentality I describe and criticize in my article.

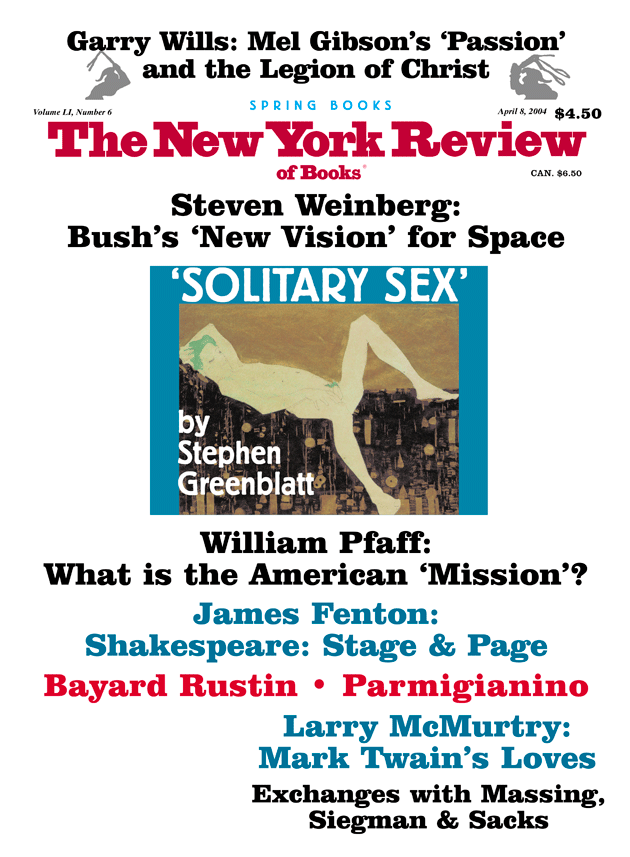

This Issue

April 8, 2004