Serendip. Its exquisite placement—poring over the map in school, we used to think it was like a precious pendant suspended from the necklace shape of India, lying on the breast of the Indian Ocean—and the very name of the island conjure up a vision of an earthly paradise. So it must have seemed to the Arab seafarers who named it on coming upon it in their hazardous voyages, with its luxuriant vegetation, flamboyant wildlife, treasure trove of gems, and long surf-washed coastline. The words “earthly paradise” are not idly used either since in Muslim legend it was to earthly paradise that Adam and Eve were exiled after their expulsion from the heavenly Eden.

The literature that has come from there has supported the idea. There is the Persian fairy tale The Three Princes of Serendip, about the travels and the adventures of the eponymous heroes, which led Horace Walpole, in 1754, to coin the term “serendipity” for the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident. John Barth played with the link between the word and its etymology in his book of 1991, The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor. In a more realistic vein, there was Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, which, idiosyncratic and ultimately tragic as it might have been, entranced its readers with its gorgeous embellishments. There was also his Anil’s Ghost (2001), which led the reader into some magical grove where mysterious secrets were uncovered.

And now there is Michelle de Kretser’s The Hamilton Case. It ratifies every dream one might have of a tropical landscape with its account of a rich and eccentric family and its complex and serpentine history. She is, however, as smart and up-to-date as can be about the world of postmodernism, perfectly aware of all its conventions while capable of mocking them even as she uses them.

Prominent in the novel is the disreputable and scandalous Maud, the mother of the main character, Sam Obeysekere, who is incarcerated in the family mansion in the jungle by her son and driven by her loneliness and silence into obsessively writing letters to everyone she has ever known. She transforms the nightmare world she occupies into a romantic fiction; in her letters bougainvillea is “unfailingly rampant,” the jungle “teemed with life,” the evening air is “filled with the scent of jasmine,” and the monsoon rain is “a silvery shower.” The author comments that “it was not her intention to deceive. There is an old instinct, at work in bordellos and the relations of East and West, to convert the unbearable into the picturesque.”

Another of her characters, Shivanathan, a provincial judge whose career has not gone well and who has turned to writing fiction, puts together a collection of short stories called, inevitably, Serendipity, and subtitled Island Epiphanies. Sam Obeysekere, who has known the author, checks it out of the library, knowing

there will be breasts that resemble ripe mangoes…. Hair lustrous with coconut oil will alternately ripple and cascade. And I very much fear there’ll be a barefoot old woman in spotless white who will eat curries with her fingers and perform simple devotions to her gods.

For all his cynicism, he laments that “I’m part of it all too, like it or not, I’m as authentic as any bally mango.”

De Kretser, a Sri Lankan who has lived since the age of fourteen in Australia, is not herself immune to the allure of the exotic even if she does not succumb to its clichés. Still, it is impossible to describe her prose as anything but rich, luxuriant, intense, and gorgeous. Reading it is like taking a walk through a tropical hothouse where orchids are “an extravagance of bruised kisses,” cockroaches are as “glossy as dates,” a wasp’s nest is “a pale stucco mansion,” and “leaves mocked grav-ity, rising into the air. There they resolved themselves into a billow of jade butterflies.”

The tropics and the legend of the exotic East that have inspired so much (mostly second-rate) fiction are but one of the influences on—or targets of—her writing. There is also the blithe between-wars hilarity of P.G. Wodehouse to be detected in her characterization of Sam’s father, known to him as Pater and to Maud, his wife, as Ritzy (in fact they first met at the Savoy; using the name of the wrong hotel “revealed her disdain for detail”); and we have the speech used by the fast set of Colombo (of a Buddhist: “Lectured me on the taking of life and whatnot. Blighter’s bleeding me to death in the courts but that’s different, it seems”). Also, the strict narrative rules of the detective fiction of the time are followed in the unraveling of the Hamilton case—the murder of an English planter—when the least likely suspect is found by the court to be the murderer. Yet at the end of the novel, one of the judges, brought up in the tradition, casts doubt on the verdict:

Advertisement

Twenty-five years have passed since I read Hercule Poirot’s Christmas…. Yet I saw that I had—quite unconsciously—plucked out the crucial elements of Mrs. Christie’s plot and grafted them onto the Hamilton case…. I saw that I had fallen for an old enchantment. I had mistaken the world for a book.

But by placing this revised version of the book at the end of the case, he admits:

I’ve lent it credence. We believe the explanation we hear last. It’s one of the ways in which narrative influences our perception of truth. We crave finality, an end to interpretation, not seeing that this too, the tying up of all loose ends in the last chapter, is only a storyteller’s ruse. The device runs contrary to experience, wouldn’t you say? Time never simplifies—it unravels and complicates. Guilty parties show up everywhere. The plot does nothing but thicken.

So does de Kretser take the literary traditions of the novels from the 1920s to the 1940s and turn them into the postmodern fiction of our times—mocking, cynical, sophisticated, and bitterly aware. Like Hari Kunzru in The Impressionist, she employs all the literary devices of empire from Rudyard Kipling to Somerset Maugham to Paul Scott, and then lays bare the backstage truth to disillusion the reader. It is a dazzling performance.

Until one grasps her motives and intentions, one might wonder at her lending so much weight to the somewhat commonplace tea plantation scandal that gives her novel its title: after the English planter is found murdered, two coolies on the estate are arrested as suspects, then another planter’s wife—English, pregnant, and, in her pastel outfit and pallor, the very symbol of the Empire’s purity—gives testimony and, in a scene of courtroom melodrama, accuses her own husband of the crime, the first time an Englishman in the colony has been accused of murder. He is found guilty and condemned to hang.

One of the jurors—“British to a man, shop keepers, shipping agents, an engineer”—tells a newspaper reporter that

he had been tormented all weekend by the delicate problem of how a sentence of death might be carried out. That a native should hang an Englishman was unthinkable. But could one count on the government, always unreliable over essentials, to go to the expense of bringing in a hangman from Home? That uncertainty alone was enough, said the juror, to ensure that he, for one, would not have returned a Guilty verdict.

In the event, the condemned man lets him out of his dilemma by performing the deed himself, in his prison cell.

This tawdry melodrama not only gives the novel its title but allows de Kretser to use the device of shifting interpretations to keep up the tension and the suspense to the very last page. It also gives the novel its curious construction: Part I is told in the first-person voice of Sam Obeysekere, the lawyer who brings about the acquittal of the coolies and the guilty verdict on the English planter; Part II adheres to his point of view but the voice changes to the third person; in Part III we are presented an omniscient point of view; and in Part IV there is a shift to the epistolary style, allowing us to hear another view of what happened, that of the principal judge. Although it is the last we hear, it is not conclusive. The author points out that “history, like any other verdict, is not a matter of fact but a point of view.”

Sam Obeysekere entertains no such doubts and vacillations. It is his nature, and his training, to pursue clues in a logical fashion, subject them to reason, and arrive at a conclusion. As a student in England, he had exulted that

I was living in the heyday of the English murder…. I was most impressed by the cold brilliance with which the great English murderers planned their crimes, the slow maturation of the project in logic and cunning over weeks and months. It was quite the converse of the way things were done at home. There, lack of premeditation was the rule…. There was no art to such crimes. The psychology of the murderers was as simple and dull as the alphabet. In many cases the killer made no effort whatsoever to avoid detection and was apprehended at once by the authorities. It struck me as a thoroughly brutish state of affairs.

From the art of murder it was a short step to murder as art. It was at this time that I discovered the complex pleasures of the detective novel. I was soon immersed in Conan Doyle and E.C. Bentley, and the early works of the sublime Mrs. Christie…. I loved to sharpen my wits on the ingenious puzzles devised by their authors, and may say without vanity that once or twice I succeeded in cracking them before the solution was revealed in the final pages. Mod-esty compels me to add that the unraveling of the Hamilton case… probably owed more to a mind steeped in the strategies of detective fiction than to the genius with which I was credited by so many commentators.

What is ironic, and uncharacteristic, about his handling of the case is that it was an Englishman he condemned. He was brought up to see the English as his superiors, even his leaders, precisely the kind of person the British regime had hoped to create. He came from a family of mudaliyars, men who were traditionally assistants to rulers, the Kandyan kingdom to begin with, then the colonial administration for whom they were “record-keepers, …intermediaries and interpreters,” and dealt with “native disputes concerning land, contracts and debts.” This earned them rewards from the Europeans—the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British—and they acquired vast tax-free estates and, sometimes, knighthoods. Unfortunately, Sam’s grandfather, Sir Stanley, disgraced himself by plunging into a lake to rescue an English girl who, while out rowing, had fallen overboard. This was considered such an outrage that the girl’s companion brought her oar down on his skull. “He drowned, of course,” and the girl was rescued by some Scottish engineers who happened to be present. The English thought Sir Stanley’s act proof of the Ceylonese being “prone to exaggeration.” Murmurs of anti-British sentiment among the Sinhalese were quelled by Sam’s great-uncle Willy writing a letter to the Times of Ceylon “regret-ting his brother’s impetuousness” and absolving the English oar-wielder of all blame. Michelle de Kretser’s humor tends to the darkest shade. She has Sam inform us that Great-Uncle Willy never did get the OBE he yearned for:

Advertisement

The English have long memories, you see. Their great talent lies in the reconciliation of justice and compromise. A formidable race. I miss them to this day.

In fact Sam’s family might be said to belong to the school of Exotic Gothic or Gothic Exotica. There is Pater, a Bertie Wooster–like character, feckless and charming. He buys champagne by the twelve dozen and throws parties that last until dawn. His generosity is legendary—and painful for his family:

I learned to keep my prized possessions hidden away after Pater spotted my beloved lead soldiers on the verandah, scooped up the Duke of Wellington and pressed him into the grubby hands of our cook-woman’s grandson. I flew at the brat and kicked at his ringwormed shins, for which I earned myself a thrashing.

Another time, an overconscientious overseer brings to him his own son who has been caught stealing coconuts, and Pater sets his jaw, does his duty, and whips the boy till his back bleeds, then rushes off to vomit in revulsion, and is later found to have supported the boy in his career for as long as he lived.

He meets his match in Mater,

a great beauty. Also, a first-rate shot…. It was alleged that she once swam in a jungle pool wearing only her bloomers, even though there were gentlemen and snakes present.

Also, “She was a great smasher…. Crystal was her speciality. My father took pains to ensure she always had a supply of costly glassware at hand.”

Colorful behavior, but what Sam remembers most about them is “that they weren’t there.” Once the parties were over, they left.

I used to line up the empty bottles along the verandah and shoot them with my air rifle. That’s what comes to mind when I think of my childhood: a boy in short trousers and long socks, the listless, bright, empty afternoons, birds flying up from the leaves at the first explosion.

Not an uncommon story in colonial times. Their house filled to bursting with “the fabulous flotsam of Empire”—the lacquer boxes, opium pipes, ostrich eggs, objects of jade and ivory as well as seashell trays from Brighton and leather camels from Aden, for “no distinction was made between the relative worth of these articles…. All served equally to link our old house, dozing in the jungle, with the great electric world of merchants and machinery—“ so that later, in London, he comes upon Selfridge’s emporium with the delight of recognition: “A cornucopia of disparate items…collected en bloc from every outpost of the globe.”

Only the parents were missing, so painfully absent that when Mater did deign to visit, he would run to her and “grasp her about the knees. Sometimes, not knowing how else to express my longing, I sank my teeth into the folds of her skirt and worried the material.” On one heartbroken occasion, when he presses his lips to “Mater’s cigarette-scented cheek and wound my arms about her neck,” she disentangles herself, saying lightly, “Goodness, Sam…anyone would think you had a claim on my affections and whatnot.” The author comments, “Among a set that valued astringency in human relations, her style passed as good form.”

When Sam is old enough to leave the nursery, it is to St. Edward’s School in Colombo, known affectionately by its pupils as Neddy’s, that he is sent as a boarder. In a chapter entitled “Sons of Empire” we are told with pride that it

had been founded in 1862 by an Anglican bishop on the pattern of Eton and Rugby. There, some five hundred boys were educated in English, Classics, Mathematics, Divinity and the Sciences. Many of us went on to Oxford and Cambridge, and returned home to forge illustrious careers. Government, the judiciary, medicine, education: to this day Old Edwardians are disproportionately represented in all the leading professions….

Most of us Edwardians came from Sinhalese or Burgher families, but there were several Tamils amongst our number, a sprinkling of Moors and Chinks, an Indian from Bangalore and even two woolly-headed brothers from East Africa. But racial distinctions were played down at Neddy’s, as a matter of school policy. We were Edwardians first and Ceylonese a long way second. Of course a fellow’s name proclaimed him a Sinhalese or a Tamil, a Burgher or a Moor; but these distinctions passed almost unnoticed.

Even later in life, Sam can say:

I am proud to have attended Neddy’s in the days when it turned out gentlemen and scholars. As a boy I often thought what a great pity it was that Ceylon had no empire of her own; we Edwardians would have made such a splendid job of sallying forth and ruling it.

It is here that Sam forms the social set that will be his for life, and it provides the novel with its other characters—Jayasinghe, a Sinhalese who will become a politician and the leader of the nationalistic Sinhalese People’s Party, and the Tamil Shivanathan, later to become the judge who writes short stories. These are not exactly friendships—acquaintances of long standing, certainly, but rivalries would describe them better. Jayasinghe very early on gives Sam another name: when, as prefect, Sam reports a boy who has played a trick on an English master, Jayasinghe tells him:

Your people were Buddhists under our kings, Catholics under the Portuguese, Reformists under the Dutch, Anglicans under the English. You can’t help yourself, can you? Obey by name, Obey by nature.

Sam is hurt but cannot contradict the taunt. “I could have argued there is no shame in adaptability and keeping an open mind.”

So very adaptable—and impressionable—is he that he needs only to catch the fragrance of a pine tree on a Ceylonese hill to think that “England would smell like that: deep and crisp and even.” Oxford is the logical next step in learning to be that complex creature, a son of the Empire. This chapter is of course titled “The Dreaming Spires,” and Sam keeps his eyes firmly on them and on “the river slow and green, stonework like sculpted honey,” his mind on games of tennis and tea in the pavilion. It is not that he is impervious to the scholars walking “disdainfully” past him or to his lack of success with English girls:

How I yearned for one of them, more discerning than her sisters, to see beyond my appearance to the delicate play of intellect and wit in a mind nurtured on all that was finest in literature and philosophy. I am not what I seem, I wanted to cry. I am no different from your brothers. We have read the same poems. But those bloodless lips twisted, and the girls looked away.

He leaves Oxford for Gray’s Inn, the golden lads and lasses for London prostitutes, and in time is called to the Bar. On learning of the sudden death of Pater—who suffers a heart attack while riding in Queen Victoria Park—Sam returns to Ceylon, deals with the vast debts left him to pay, and launches himself on a legal career with the hope of eventually entering government service. To this end he even participates in that rite of passage in the life of a civil servant—shooting an elephant, as sickening a slaughter as can be imagined. His fellow hunter, Jayasinghe, comes upon a mother and calf peacefully foraging, shoots the calf, and strikes the required pose over its corpse; in a parody of the triumphant hunter’s pose,

the usual proportions are reversed: the elephant is small, the hunter looms large. Instead of evoking a noble victory of man over nature, the image suggests a shabby little coup.

De Kretser’s metaphors are not always so brutal. She can actually get the same effect by showing us Sam as hunter: “Within a quarter of an hour I had a brace of small green pigeon whose bubbling calls had greeted us on arrival.”

Sam’s career proceeds well and he soon acquires “a reputation for brilliance.” It is what leads, or misleads, him into taking up the Hamilton case and ruining it by finding an Englishman guilty. He performs this daring act because “I know the English, old boy. Fair play and all that,” only to have Sir George North, the King’s advocate, send for him and inform him, affably and vaguely, “Word to the wise. The judiciary…Personal discretion, don’t you know. Limelight not entirely…” and Judge Shivanathan gets the promotion to district judge that Sam craves.

Sam might have dated the decline of his fortunes from that moment—if he were ever to admit the possibility of a personal decline. Instead, he blames the increasing seediness of his life on the general decline of the Empire, dating it from World War II and the simultaneous strengthening of the independence movement. When the newspaper at breakfast one morning announces “Labor Landslide!” he senses that

now it would be only a matter of time before [the British] extricated themselves from the island as if they had never been there. A century and a half swilled down the drain like a discharge not referred to in polite company. And there he would be, high and dry and thousands of fellows like him, craving the subtleties of marmalade and obliged to make do with pineapple bally jam.

Sam and the others in his set see the now inevitable exit of the British as leading to all the vulgarity and inferiority of present times:

New stamps, hula hoops, ration books, flocked nylon, rising prices, a falling currency, Coca-Cola, cabinet ministers in sarongs, ladies in trouser suits, failed coups, successful assassinations, race riots and a national anthem no one knew the words to. A generation left marooned on verandahs, eking out its grievances like whiskey and sodas.

Jayasinghe, who had once been shown the door when he turned up at the governor’s ball in a dinner jacket and a sarong, becomes the minister of culture in the new government and eventually founds a new party. Sam, on the other hand, insists on giving formal dinner parties on the erstwhile Empire Day:

He felt it was a plucky, rather fine gesture: the Collector in the doomed residency running up the standard. At the same time he resented the role. It had been imposed on him. They had thrust him into anachronism.

It is Shivanathan who tries to elucidate Sam’s character and life. He had, he says,

the gift of perfect mimicry, you see…. If you would put your hand on the key to him, study that ventriloquism. I find it unbearably sad.

The last image we have of him is of his walking down to the postbox to look for a letter from his son in England, and turning away empty-handed, returning to his increasingly desolate house to write down his memories of the Hamilton case.

Wrapped around this public and political story from Ceylon, though, are the suffocating vines and tendrils of the private lives of women like Sam’s mother, Maud, his sister, Claudia, and his wife, Leela. To tell their stories, de Kretser abandons the language of public schools and colonial service and employs a voice far more dark, intense, and disturbing. Here it is the Gothic tradition in literature that takes over, and the oral tradition of witchcraft and superstition. Leela, the wife, spends her days on a veranda, “neither inside nor outside the house,” where Sam, “coming upon her…one morning as she sat with folded hands in watery green light, thought of a slug clamped moistly to its leaf, and shuddered, and went away without a word.” When his mother grows too embarrassing, in her poverty, for polite society, he incarcerates her in the old family home in the jungle, instructing the caretaker to turn away all visitors. Out of her solitary imprisonment, she sends out letters to everyone she has ever known. On receiving no replies, she takes to filling notebooks with her observations of nature just as an English governess had taught her long ago to do—a bird watcher’s list, the medicinal properties of jungle plants, notes on experiments with plants….

Maud sensed it was absurd to go about the world pen in hand, as if its variety and chaos and appalling detail could be corseted within royal-blue copperplate.

It creates in her a hypersensitivity to color, light, and smell that is supernatural in its intensity:

It was an interval of heightened, almost painful sensations. Objects she handled unthinkingly—a towel, a nail file—turned velvety and repulsive to the touch. Colours flared more forcefully, and translated themselves into flavors, the blue-black of a crow experienced as a thick plummy sweetness, the scarlet of a canna rising in her nose like mustard. The place would not be reduced to background. It cast nets of leaves about her. It caressed her arms with its warm yellow tongue.

The supernatural is in fact what is summoned:

There was a snake coiled on Maud’s pillow. She shouted and sprang away but…it was only her housecoat, a careless twist of chiffon. The lid of a tureen became a mirror that reflected everything except her face. She reached for a cake of gardenia soap and found it fringed with fish hooks. There was also a bird, feathered brown and dusty purple, perched on a brass curtain rod or stepping along the back of a chair; or, horribly, gazing up at her, a prickle of claws along her instep.

At the far end of the verandah, a child slid into view….

The family home, engulfed by “the soft snarl of the jungle,” teems with secrets, mysteries, unexplained deaths, and unquiet ghosts. Maud is tormented by the devil-bird’s scream: “Magai lamaya ko? Where is my child.” She hears sobbing on the other side of the wall. Fragments of the suppressed and supposedly forgotten past haunt her and make no more sense now than they did then. Sam’s sister Claudia as a little girl is inconsolable if she is separated from a small, filthy pillow to worry with her fingers. A pillow lies on the floor of an empty room. A small boy appears, holding it, and vanishes. Even electric light will not vanquish these shades; it casts only “a weak, grayish light. It suggested something haggard waiting just beyond its reach.”

Maud takes to flitting about the jungle, dressed in the rags and tatters of her once elegant brocade and taffeta dresses:

Things slipped out of their elements. A human face might peer at her from the chipped brickwork of a wall. Mosses grew eyes and moved. Tiny fish, vivid as gems, glowed briefly among ferns. Four headless mandarins in funereal kimonos paraded before her, on a log where a row of cormorants had stood with wings stretched wide as they picked lice from their pinions. Once, in the unambiguous glare of noon, a figure walked less than six feet ahead of her on the road. It was neither male nor female, and its skin was a luminous coppery blue.

These phenomena no longer bothered Maud. They were integral to the place in the way her presence was not. If whatever sent them had a message for her, it would be revealed in time. She accepted them, and they left her alone.

It is left to Sam in his final moments to reveal the secrets to us. He is at last done with his memoir and he could not

understand now why he had ever granted the Hamilton case any significance. Why had he set out to disentangle its chain of cause and effect? He had allowed a sideshow to distract him from the drama of his own history.

That drama, that history, had been at the center, the heart, and only now does it overtake him.

Like him, the reader too will feel misled. So much was made of the Hamilton case that it created the impression that it was central to Sam’s life and being. It was not. Something far more terrible was—but instead of coming as a revelation, it exposes a gap: we had been made aware of Sam’s unappeased passion for his mother, his almost pathological obsession with his sister, but we had not known—or not known much—of another child, Sam’s brother, Leo, who died as an infant, and Sam’s insane jealousy of him. The rules of detective fiction have been followed—but prove somehow unsatisfactory in literature.

This raises questions about how the novel has been constructed. In such a “teeming jungle” of interlocking stories, inevitably some characters and stories will be large and strong, others cast into the shade and smothered. A writer, like a painter, selects what is to be highlighted and what is to be left in the background. In the end, though, the reader cannot help regretting that while we heard so much of certain voices—Sam’s and Shivanathan’s—we heard so little of others, potentially more interesting—e.g., Jayasinghe’s—while of the three women, one was silent, another whispered, and the third ranted like a crazy person. De Kretser shows great aplomb in creating a garden within this jungle, but ultimately it is the law of the jungle that prevails.

It is interesting to note that the Persian legend The Three Princes of Serendip does not so much describe lucky accidents and discoveries as it relates a case of clever sleuthing whereby a runaway camel is tracked down. It seems that was the legend to which de Kretser was hewing rather than to Walpole’s interpretation of it.

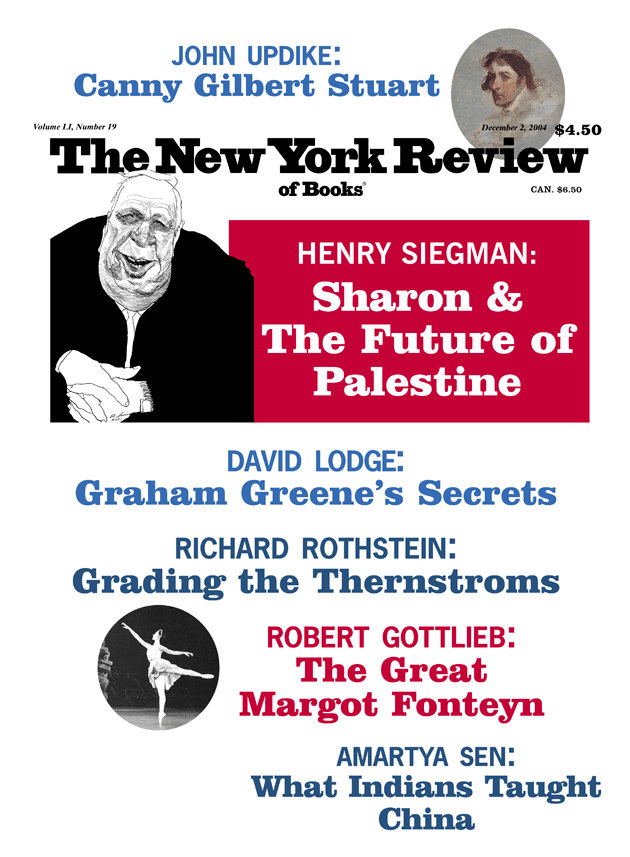

This Issue

December 2, 2004