“Oh please, Nurse, tell me again how the French came to Moscow.” Thus the writer Alexander Herzen starts My Past and Thoughts, one of the great works of nineteenth-century Russian literature. Born in 1812, Herzen had a special fondness for his nanny’s stories of that year. His family had been forced to flee the fire that engulfed Moscow on its capture by the French, and it was only through a safe conduct pass from Napoleon himself that they managed to escape to their country residence. Herzen was proud to have “taken part in the Great War” (he had been carried out in his mother’s arms). The story of his childhood became part of the national drama he so loved to hear about: “Tales of the fire of Moscow, of the battle of Borodino, of the Berezina, of the taking of Paris, were my cradle songs, my nursery stories, my Iliad and my Odyssey.”*

History and myth are intertwined in the story of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. It is a story of such epic scale, one retold so often and so closely linked to national cults and works of fiction, including Tolstoy’s War and Peace, that sometimes it appears more legendary than real. In France the tragedy of the retreat from Moscow gave birth to the Napoleonic myth of greatness in adversity, of the superhuman hero in a battle with his fate, which inspired the Romantic imagination. In Russia the memory of 1812 was central to forming powerful political mythologies about the Russian people and their destiny, which in turn shaped the national and personal identity of educated Russians in the nineteenth century.

For democrats, like Herzen, the war against Napoleon was a “people’s war.” It was the point at which the Russians, as a nation, came of age, and with their triumphant entry into Europe, the moment when they should have joined the family of modern European states. But for conservatives, the war symbolized the holy triumph of the Russian autocratic principle, which alone saved Europe from Napoleon.

From these two historical mythologies, a “Russian version” of the war emerged in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. In personal memoirs, history books, and novels, the war against Napoleon was portrayed as a “patriotic war.” In this version the Russians had prevailed through “Russian principles”—through their patriotic sacrifice, their stoical resilience and military cunning, as exemplified by their greatest commander, the “Russian hero” Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov, who lured the Grande Armée into a fatal trap by retreating deep into the continent and waiting for the Russian winter to destroy the French.

By and large, this was the view in Russia until the Revolution of 1917, when the idea of patriotic Russian peasants fighting for the tsarist cause was rejected. But Stalin encouraged a return to the traditional view following Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, when the “Patriotic War of 1812” was recast as a sort of dress rehearsal for the “Great Patriotic War” of 1941–1945 (with Stalin in the role of Savior of the Fatherland). The idea of a “patriotic war” continued to dominate Soviet historiography until the policies of glasnost in the 1980s, when a new generation of historians began to look at the historical evidence in a more objective way.

Adam Zamoyski has drawn upon their work in Moscow 1812. It is a magnificent achievement, a richly detailed and highly readable account of Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Russia which sweeps away all the national myths in order to reveal the true face of this senseless and horrific war. Zamoyski does not claim to have carried out original research in the archives, and at times, as in his discussion of the Russian peasant partisans, where he is forced to borrow from the work of Soviet historians, the lack of archival evidence reduces his authority. But Zamoyski’s great strength is his command of languages, which enables him to cite from a wider range of published sources than previous historians have done.

Napoleon’s Grande Armée was a multinational force made up of soldiers from all parts of the European continent. Zamoyski draws from an extraordinary range of French, Russian, German, Polish, and Italian eyewitness accounts, some of them familiar to English readers, such as the memoirs of the French officer Philippe de Ségur, but many of them new to those without Zamoyski’s languages. The liberal citation of these memoirs brings to life Zamoyski’s narrative, which vividly conveys the ordinary soldier’s experience of the war. This effect is further strengthened by the well-selected illustrations, mostly by participants directly on the scene, which convey the human side of war with an almost photographic realism. Zamoyski is particularly successful in letting his readers feel the chaos and the horror of the battlefield.

Advertisement

1.

Zamoyski begins his sweeping narrative with the birth of Napoleon’s heir, the King of Rome, in March 1811. Napoleon was master of Europe, and only Britain, with its powerful navy and the Duke of Wellington’s campaign in Spain, was a military threat. Tsar Alexander I saw himself as the defender of the Christian monarchical tradition, and between 1805 and 1807 the Russians had joined Austria and Prussia in a crusade against the “Antichrist” Napoleon. But they were defeated by the French on the battlefields of Austerlitz and Eylau. In July 1807, Russia became an ally of the French, when Alexander met Napoleon on a raft moored in the middle of the river Niemen and signed theTreaty of Tilsit. According to the treaty, Russia agreed to the French occupation of Prussia and to the creation of a Grand Duchy of Warsaw. It also had to agree to join Napoleon’s continental blockade against British trade.

As Zamoyski makes clear, the Russo-French alliance was unstable from the start. Alexander viewed the “liberal empire” of the French as a mortal threat to the three pillars of the tsarist state: orthodoxy, serfdom, and autocracy. The creation of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, which threatened to restore an enlarged Kingdom of Poland, brought the Napoleonic peril right up to the borders of Russia’s western lands, where the Tsar’s Polish subjects “could potentially form a terrible fifth column of Western corruption inside the Russian empire.” Russian patriots, wounded by the humiliating defeats of the years between 1805 and 1807, succumbed to the paranoid conviction

that France under the satanic leadership of Napoleon was bent on the subjugation of Russia, and that Tilsit…was but a truce putting off the terrible day.

Russian fears of French aggression were strengthened when, in 1810, the Swedes elected one of Napoleon’s marshals, Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, to be crown prince and ruler of Sweden. These fears were given added strength by the economic hardships of the blockade, which spiraled to affect the whole of Europe’s shipping trade, depriving Russian landowners of valuable markets for their timber, grain, and hemp, and forcing them to pay far higher prices for imported luxuries. Although steeped in French culture, the Russian aristocracy succumbed to a latent resentment, and sometimes hatred, of France.

Under pressure from this enraged élite opinion, the Tsar toughened his defense of Russia’s interests against France. At a time when Napoleon was struggling to deal with Wellington in Spain, Alexander reneged on his treaty obligations to maintain the continental blockade of Britain and sought more concessions from the French to maintain the alliance against Britain. Napoleon saw this as a sign of Russian aggression. He feared that Russia was threatening to expand into the heart of French-dominated Europe. He convinced himself that the buildup of Russian troops on the borders of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw was part of a plan to attack the French Empire the moment that he left to deal with Spain, or to conquer bits of Polish land and then bully France into accepting these conquests as the price of Russia’s continuation in the alliance against Britain. Napoleon refused to be bullied. He would not buy Russia’s adherence to the Treaty of Tilsit by ceding to it any part of Polish territory. So he prepared for war “to be in a position to dictate a peace.”

On June 24, 1812, Napoleon led his troops across the Russian border on the river Niemen in the belief, or perhaps the hope, that a swift and decisive engagement with the Russian army would force the Tsar to accept his terms. But Alexander remained firm: he refused to sign a peace treaty that was dictated by a French force which had arrived on Russian soil. Through mutual fear and aggressive posturing the two great powers thus drifted into war. Napoleon later wrote that they had got themselves “into the position of two blustering braggarts who, having no wish to fight each other, seek to frighten each other.”

In Moscow 1812 Napoleon appears as a man driven by a limitless belief in his own destiny yet strangely indecisive and uncertain of himself in realizing his plans. In Zamoyski’s account, he is a long way from the legendary image of the willful genius. The legend, to be sure, managed to retain its charismatic power among the soldiers of the Grande Armée, and throughout the book Zamoyski notes, with rising astonishment, that however badly the campaign went, there were always troopers who remained inspired by the propaganda cult of Napoleon. But time and time again Zamoyski presents evidence of Napoleon’s hesitation and military blunders, which wasted some half a million lives.

From the start, the entire campaign in Russia was ill-conceived. Napoleon did not learn from the accounts of Charles XII’s disastrous march into Russia a hundred years before. (Voltaire claimed that any ruler who read his own history of the Swedish king would be “cured of the folly of conquest.”) Napoleon dismissed the arguments against attacking Russia because of its climate and the enormous distances his armies would have to travel (though he appears to have had doubts, and all the way to Moscow, according to Zamoyski, he kept within his reach a well-thumbed copy of Voltaire’s history). He drifted into war without really knowing what his war aims were—and “by definition,” as Zamoyski notes, “aimless wars cannot be won.” Napoleon did not want to destroy the Russian state (his refusal to support the Polish cause was proof of that)—he wanted only to shake and frighten it until the Tsar gave in to his political demands. But that aim was nullified when the Russians fell back and refused to fight. Napoleon marched on to Moscow, hoping that the fall of the ancient city would force Alexander to submit.

Advertisement

But the conquest of Moscow was a strange war aim: it was not the seat of government and its loss, though damaging to the prestige of the Russian state, did not in any way undermine its military power or authority. If the purpose of Napoleon’s campaign was to impose his will on the tsarist government, then one has to ask a question that is missing from Zamoyski’s book: Why did Napoleon not march directly to St. Petersburg? In fact, after he had conquered Moscow and concluded that the Tsar would not give in, Napoleon considered marching with a smaller army to St. Petersburg. But by then it was too late.

2.

The invasion force that crossed the river Niemen on June 24 was the largest army the world had ever seen—over half a million men of almost every European nationality. The success of the Grande Armée had always depended on its ability to travel light, feeding off the land, but this tactic was not feasible in Russia, where the country was too poor and thinly populated to support so many troops. Napoleon had planned for a huge supply machine to follow the Grande Armée to Moscow, but there was a shortage of draft horses, and it never quite materialized. Looting began in the Polish lands, potentially a key supply base and political ally in the war against Russia. “The Frenchman came to remove our fetters,” the Polish peasants said, “but he took our boots too.”

As they moved east, conditions worsened for the Grande Armée. Stone roads turned to dusty tracks. Distances increased between the villages. The horses suffered terribly. Troops went days without a meal or a bed of straw. Water became so hard to find that, in the scorching July heat, when daytime temperatures reached nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the men drank almost anything, even horse’s urine, to quench their thirst. Thousands died from dehydration and dysentery, particularly the Germans, who, Zamoyski says, were less resourceful than the French and other troops at surviving on the road.

The entire army suffered from diarrhea. Once the army passed, it left behind on the road from Vilna to Moscow one long trail of human excrement, the carcasses of horses, and the bodies of dead men. “On some stretches of the road I had to hold my breath in order not to bring up liver and lungs, and even to lie down until the need to vomit had died down,” wrote one German officer. Some soldiers later reflected that the advance into Russia had been even worse than the infamous retreat, and statistics give some substance to this perception: by the time it reached Vitebsk, long before it fought its first battle, the Grande Armée had lost one third of its men.

Napoleon was trying to engage the tsarist army in battle. But the Russian forces, under the command of General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, kept falling back, and, apart from an improvised and unsuccessful defense of the city of Smolensk, offered no resistance to the French. Zamoyski debunks the Russian legend that this was part of a clever plan to lure the Grande Armée forces into the barren heartlands of Russia and then wait for the winter to destroy them. He writes that the tsarist army fell back in confusion, its senior officers squabbling among themselves and demanding the removal of the foreigner Barclay (who realized that in these circumstances there was no point in trying to attack the French). Under pressure from public and military opinion, the Tsar replaced Barclay with the popular Kutuzov, an old hero from the Turkish wars, whose plain speech and eccentric manners were taken as the marks of a “true Russian.”

In War and Peace Tolstoy contrasts the military genius of Kutuzov, who reacts instinctively to the mood and movements of the soldier mass, with the rigid planning of Napoleon. This idea became a central part of the Russian national myth of 1812, which was portrayed by Tolstoy, among others, as a victory of “Russian spontaneity” against “Western rationality.” Zamoyski barely mentions War and Peace—and generally in his military narrative he does not find a place for a discussion of literary ideas or works of art depicting the war. This is a pity, not least because his own account of Kutuzov’s leadership does much to undermine the Tolstoyan myth.

Kutuzov engaged the French at Borodino, sixty miles to the west of Moscow, on September 7. The result was the biggest single massacre in the history of warfare up to that time, not to be surpassed until the Battle of the Somme in 1916, with 70,000 people (and 35,000 horses) killed in the course of a single day. Zamoyski gives a harrowing account of the hand-to-hand fighting. Kutuzov had no coherent strategy, Zamoyski argues. He simply reacted to urgent requests and reports. He did not even have a clear view of the battlefield, spending most of the day in the quiet fields behind Gorki, the Russian headquarters, where, according to Zamoyski, “he did justice to a fine picnic, assisted by his entourage of elegant officers from the best families.”

After Borodino the Russian army was in no condition to defend Moscow or to fight the French elsewhere. So Kutuzov’s one really brilliant decision was to abandon Moscow to the French in order to save the Russian army from defeat. Napoleon’s troops entered Moscow on September 14—only to find that the Russians had set fire to the city’s granaries and any other stores that might prove useful to the French. Napoleon gave his troops time to rest and loot the jewels and furs that, it seems, had been their major motive from the start of the campaign. And then, lacking food or fodder to survive the winter in Moscow, he ordered the retreat on October 20. Zamoyski calculates that had Napoleon retreated from Moscow two weeks earlier his army would have reached Vilna in Lithuania in good-enough condition to mount a new invasion of Russia the following spring. But Napoleon was fooled by the unusually warm weather (there was just one light snowfall on October 13). He continued to delude himself that the longer he remained in Moscow the greater were the chances that the Tsar would lose his nerve and sue for peace. Napoleon bluffed—and lost everything.

3.

Laden with booty, the Grande Armée began its retreat. Philippe de Ségur compared the army to a Tatar horde returning from a raid, with up to 40,000 wagons loaded to the hilt with precious ornaments, furniture, carpets, books, and furs, and 100,000 knapsacks filled with gold and silver jewelry. On November 5, with the advance troops just beyond Viazma, the Russian cold began to bite; the temperature dropped to 4 degrees below zero Celsius (and by the end of the month would reach 22 degrees below). Soldiers fashioned makeshift winter clothes from stolen blankets and scraps of fur, but these were not enough to withstand the frost. Thousands of men were literally struck down by the cold as they walked along. “They would slow down slightly, totter like drunken men, and then fall, never to rise again,” recalled a Polish officer.

Without sharp shoes, horses fell down on the ice, where they were left to freeze to death. The loss of the cavalry made the army vulnerable to attacks by the Cossacks, who pursued the retreating columns, and caused panic whenever they approached. “But it was the loss of thousands of draught animals that had the greatest impact on the army and its chances of survival,” Zamoyski writes. “Hundreds of vehicles had to be abandoned, some with much-needed supplies and equipment, as well as the personal effects and booty of the troops.” Soldiers carried stocks of food—though many ditched a bag of grain or rice to keep the loot which, they still hoped, would make them rich when they returned. Horsemeat was a ready source of food. But a dead horse would freeze rock-hard in a few minutes. So the soldiers sliced off steaks from living animals, or ripped open a horse’s belly and tore out its heart and liver while it was still warm with life.

Zamoyski’s account is particularly powerful in describing the soldiers’ descent from human dignity into bestiality. “Sensible men realised that their best chance of survival lay in staying with the colours, and even when regiments were all but destroyed, a kernel stuck together,” helping one another to survive. But others panicked in the desperation and fought against their comrades for a scrap of food. There were also reports of cannibalism, of soldiers “carving out the softer parts of a dying comrade of theirs in order to eat them,” and of men who were driven mad by hunger so that they began “to gnaw at their own famished bodies.”

With the Grande Armée reduced to such a state, one would have thought that a military leader of the stature of Kutuzov would have had no trouble in finishing it off. But in fact, as Zamoyski demonstrates, he was slow to take the initiative and then botched several opportunities to destroy the French. On November 15, at Krasny near Smolensk, Kutuzov split the French column, but Napoleon rode back to help the stranded troops, whereupon the Russians fled. A week later, on the river Berezina, Kutuzov let the French slip through his hands again. Both riverbanks were held by the Russians and the French were in danger of encirclement. But four hundred Dutch pontonniers stood up to their necks in the icy river and built bridges for most of the French troops to escape. It was a brilliant maneuver, a brief reminder of Napoleon’s military genius.

The remnants of the Grande Armée, by this stage little more than a rabble, reached Vilna on December 9. It was the end of the road. Of the 550,000 to 600,000 Napoleonic troops who had marched east in June, around 120,000 returned from Russia in December. The Russians lost up to 400,000 soldiers and militia, though, surprisingly, only about one quarter of them on the battlefield. They, too, suffered from hunger and the cold, a subject not explored by Zamoyski. The Russian victory owed very little to the command of Kutuzov; the Tsar was right when he said that all his successes had “been forced on him.” But how much it owed to the fighting qualities of the Russian troops or to Russian peasant partisans is not clear from Moscow 1812. We will have to wait for answers from historians who will carry out further research in the archives.

Napoleon would live to fight another day. But 1812 had destroyed the aura of invincibility that formed the basis of his charismatic power and authority. There is no doubt that this contributed to his subsequent defeats in the battles of Leipzig and Waterloo. For unless they believed in their hero’s destiny, soldiers would not fight for Bonaparte with the same passion as they had shown on the battlefields of Borodino and the Berezina. Empires crumble easily. As Napoleon himself reflected on his return from Russia, “From the sublime to the ridiculous there is but one step.”

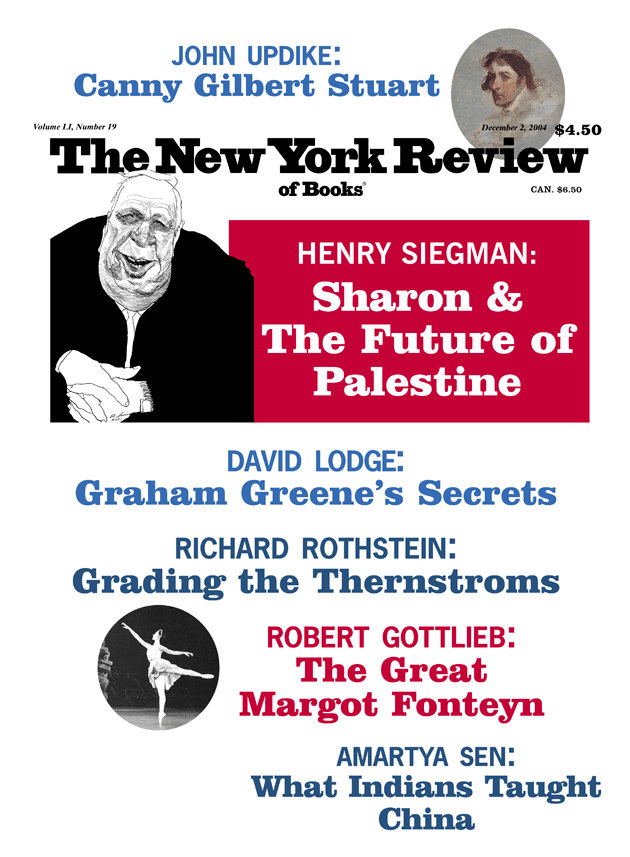

This Issue

December 2, 2004

-

*

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts, translated by Constance Garnett (Knopf, 1973), p. 10. ↩