When the late Cecil Roth retired, in 1968, after his ninth term as president of the Jewish Historical Society of England, he felt he should apologize for devoting his life to such a “modest cabbage patch.” This was, of course, the polite and appropriately English thing to do, and Roth, the first Reader in Jewish Studies at Oxford, was a very English figure. John Gross, who met him at the open house Roth kept on Saturday afternoons for Jewish students, describes him as “a tall man, with thick glasses, lots of teeth, lank black hair parted in the middle (it was often mistaken for a wig) and a spluttery voice”—in short, a typical Oxford don, except that “his conversation abounded with what you might call the higher Jewish gossip.”

There is nothing in the least apologetic about Todd Endelman’s comprehensive and authoritative history of the Jews of Britain; yet even he seems constrained by the uneventful story, as though to talk about Judaism without dwelling on suffering were historically—or even politically—incorrect:

Anglo-Jewish history in recent centuries is undramatic, at least in comparison to the travails of Jews in other lands. Show trials, pogroms, accusations of ritual murder, economic boycotts, and other persecutions that punctuated the histories of other Central and East European communities were absent, as were political revolutions, like those in France and Russia, that rapidly transformed the circumstances of Jewish life…. While the absence of violence and turmoil in their history did not disturb Britain’s Jews, who saw it as a mark of their good fortune, the same cannot be said of their historians. For them, the absence of persecution is a problem: it eliminates a familiar framework—Jews as a persecuted minority—and a set of related concepts and terms with which to view the history of Britain’s Jews. One eminent historian concluded that British Jewish history was so tranquil it did not merit professional attention.

If the British Jews are lucky to have been spared the violence that makes history interesting, so too is England. It is an island nation with a once powerful navy, and it has fought its wars abroad. Hitler’s bombers apart, the last battles on English soil were fought during the Civil War of 1642–1649, when Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians defeated the Royalist army of Charles I. Partly in response to the havoc that followed the execution of the divinely appointed king and the establishment of parliamentary democracy, Cromwell allowed the Jews, who had been expelled in 1290, to return. He did so not for the usual reasons—because he needed their financial skills and resources—but because, Endelman writes,

In the intoxicating atmosphere of those tumultuous times, many supporters of the parliamentary cause—politicians, preachers, scholars, and ordinary people alike—expected the conversion of the Jews and the coming of the millennium in the near future…. Believing that redemption was at hand and that the repeal of the [expulsion edict of 1290] would appease God’s anger over the innocent blood being shed in England, they urged that the Jews be allowed to trade and dwell in England “under the Christian banner of charity and brotherly love.”1

And that is how it happened. When Jews from the Continent began to resettle in England after 1656, they did so informally and as equals: not shut away in ghettoes and subject to special laws, but as full citizens with the same rights as any other Englishmen. Some activities were barred to them: “They could not hold civil office,” writes Endelman, “become freemen of the City of London, attend the ancient universities, or enter certain professions, since doing so required the taking of an oath ‘upon the true faith of a Christian.'” But those barriers crumbled one by one and by the middle of the nineteenth century all of them had disintegrated. In terms of British law and civil rights, a Jew, in Claude Montefiore’s words, was simply “an Englishman of the Hebrew persuasion.”

The Jews returned to England at the moment when the country was acquiring virtues the rest of Europe lacked: tolerance, freedom of worship, parliamentary democracy. Over the next three centuries, Britain was to become, in Ian Buruma’s words, “the fabled land of common sense, fairness, and good manners, the revered country governed by decent gentlemen with grand titles and liberal views, that half-mythical place where liberty, humor, and respect for the law always prevailed over the radical search for human perfection.”2 That comes from the last chapter of Anglomania, Buruma’s brilliant study of Europe’s love-hate relationship with England. The name of the chapter is “The Last Englishman” and its subject is Isaiah Berlin, a Russian Jew, born in Riga. The title is not altogether ironic since Berlin, Buruma thinks, “was his own greatest creation,” and what he created was a quintessence of the English moral decency that harried European Anglophiles yearned for, although his inspired talk and astounding intellectual range were an altogether less typically English delight.

Advertisement

For Buruma, the symbol of “the tolerant society that had attracted the French philosophes” is Bevis Marks, the Sephardic synagogue, consecrated in 1701, in the heart of the City of London. He admires it not just because it is beautiful and elegant and untouched—surrounded now by skyscrapers but still lit by candles—but because it was “built by a Quaker… [and] held together by beams donated by Queen Anne.” Three centuries ago, no other European country would have welcomed the Jews so open-handedly, and for those lucky enough to be exposed to it after a long history of discrimination, tolerance of that order was a heady and seductive mix. But it rarely comes free and in England the price of tolerance was Englishness.

The famous English class system, which nails people by accent and behavior—by the nuances of their vowels and the cut of their tweeds and by how they handle the cutlery at dinner—is an invisible web that keeps everyone remorselessly in place. But it is founded on the belief that simply being English is already an inestimable head start and the only way to be English is scrupulously to obey the customs of the country.

The class system, however, did not hinder social mobility. There were, Endelman writes,

fewer obstacles to Jewish integration in England than elsewhere in old regime Europe. Jews who wanted to mix in landed society—and had acquired the necessary qualifications—were generally able to do so. Crude stereotypes alone were not sufficient to keep them out. The gentry and aristocracy did not constitute a closed caste and were accustomed to absorbing a flow of new wealth from below. The barriers between upper and middle ranks were penetrable and elastic, unlike elsewhere. Property, even Jewish property, counted and could not be ignored.

The same rules applied further down the social scale:

On the eve of mass migration from Eastern Europe [around 1870], the majority of Jews in Britain were middle class. They were native English speakers, bourgeois in their domestic habits and public enthusiasms, full citizens of the British state, their public and personal identities increasingly shaped by the larger culture in which they lived.

That is certainly how it was for my own forebears, for example, who arrived in England, dirt poor, sometime in the eighteenth century, settled in London’s East End, scraped a living as “general dealers”—i.e., peddlers—and pen-cutters, worshiped at Bevis Marks, and married illiterate wives who signed their marriage certificates with a cross. Three generations later, their grandchildren—my great-grandparents—had moved across town and were living it up in mansions in Bloomsbury and apartments overlooking Regent’s Park.

In the United States, that would have been just another success story, though it would probably have happened faster: as they say, the difference between the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the American Psychoanalytic Association is one generation. That is all it usually takes in the melting pot to produce an authentic American. Many Americans claim to be proud of their roots and believe that ethnic differences make the stew rich. Not so in England, despite the tradition of tolerance that has made modern London as cosmopolitan and multiracial as New York. The immigrants arrive, speaking their old languages and following their old customs, and the great, slow-moving river of London churns them together and turns them into something else. That something else includes British citizenship, the right to vote, and a British passport but, no matter how long they stay, it never quite washes away the sense of being foreign. Even Quakers and Catholics, Endelman writes, felt set apart, as though, despite appearances, they, too, didn’t quite belong (and today many Pakistanis, Indians, and Bangladeshis probably feel they hardly belong at all).

The only solution is disguise and impersonation, like spies in deep cover. Hence the spectacle that so baffled me as a child on the rare occasions when my parents, who were not religious people and went only to please my grandparents, took me to the synagogue: the crowds of English gents in Savile Row suits and bowler hats, looking as if they had just stepped out of a painting by Magritte, reciting prayers in a language I didn’t understand printed in a script I couldn’t read. Hence, too, the example of a poet Endelman omits from his catalog of Anglo-Jewish writers: Siegfried Sassoon, a lapsed Sephardic Jew with a Wagnerian first name, who called his autobiography Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man. Anglo-Jewry represents the Diaspora in its most extreme form: not assimilation, but worshiping as a Jew and behaving like a goy.

Advertisement

In America, Jews are constantly asking, “Is it good for the Jews?” In England, the question is different: “Does it give the Jews a bad name?” They are concerned, that is, with appearance and behavior. During the last three decades of the nineteenth century, for example, a large influx of poor Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe, fleeing the pogroms and conscription in the tsar’s army, provoked a thunderous editorial in the Jewish Chronicle, the community’s long-established newspaper: “As long as there is a section of Jews in England who proclaim themselves aliens by their mode of life, by their very looks, by every word they utter, so long will the entire community be an object of distrust to Englishmen.”3 In England, where appearances matter a great deal, social embarrassment and anti-Semitism are always entwined.

And not only for the Jews. The government, too, felt constrained by a gentleman’s code. According to Endelman, the Aliens Act of 1905 was designed solely to limit the influx of Ost-Juden, but the “restrictionists in Parliament felt compelled to deny their anti-Semitism. In other national legislatures, it was a badge of honor.” This does not mean the English liked the Jews; they simply expressed their dislike more obliquely than others did elsewhere. Even the lower classes were too polite for pogroms, so they made do with the Shylock stereotype: Jews were crafty, untrustworthy, and obsessed with money—swarthy figures with hooked noses, waiting to do down innocent Gentiles. Further up the social ladder, the class system kicked in and anti-Semitism became a subtle form of snobbery: being Jewish was a social gaffe, like dropping your aitches; it didn’t matter how well-mannered or cultured they might be, Jews, apart from a few grandees, weren’t gentlemen.

Or rather, that is how they were made to feel. John Gross calls his memoir of “growing up English and Jewish in London” A Double Thread. He might equally have called it “A Double Bind,” though from the outside it seems like a success story—from the Pale of Settlement to the Beefsteak Club in three generations. Gross himself is a distinguished man of letters, with all the credentials an English gentleman needs: a good school, an Oxford degree, a spell as a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and as editor of the Times Literary Supplement. More importantly, his father, the central figure of the book and a powerful influence on his son, was also a gentleman in the true sense: “He was patient, forbearing and slow to condemn. He got on with people; he took it for granted that we had to live in a world where there were, in the great phrase, ‘all sorts and conditions of men.'”

As Gross describes him, he sounds like Chaucer’s “parfit, gentil knight,” despite the fact that he was a Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jew who had been studying at a yeshiva when his parents emigrated from Eastern Europe in 1913. In London, they settled in the East End and he continued his Talmudic studies. Then he switched to medicine, was accepted at Bart’s Hospital—not easy for a Polish Jew in those days—qualified as a doctor, and set up practice in Whitechapel. His patients were Cockneys, Jews, Irish, and, later, West Indians, all of them poor, and he stayed there the rest of his life.

Because of the war, however, his wife and two sons got out for a while. They were evacuated briefly to a farm in Shropshire—“the first non-Jewish home I had ever stayed in,” Gross says, and it remains, in retrospect, a pastoral idyll. They moved on to a village in Sussex, and finally settled in Egham, a placid little town in Surrey, not far from London. There were very few Jews in Egham and also no anti-Semitism that Gross can recall: “I never suffered on account of being Jewish, never felt that my future was hemmed in, never endured either literal or metaphorical blows. The general attitude I encountered was one of casual acceptance.”

Egham also gave him a crash course in Englishness, and Englishness is what Gross describes best. He has an encyclopedic memory for the details of life in Britain during the 1940s and 1950s: for vanished brands and the jingles that advertised them, for music hall songs, intimate review artistes, old movies and their now forgotten stars, for comic magazines like Beano and Dandy, Hotspur and Wizard, and popular radio shows like ITMA, Children’s Hour, Saturday Night Theatre. Gross’s recall of these “thousand trivial facts” is so effortless and vivid that he seems almost ashamed of it. Then he adds, disarmingly, “All very pedantic, no doubt; but pedantry—caring about small things—can sometimes be a sign of love.”

All the while, Gross was growing away from his Jewish roots. He was a shy, timid child, maybe a little depressed, who made few friends and kept to himself: “I hated scenes. I longed to distance myself from what I privately thought of (I don’t know where I had picked up the phrase) as “Jewish emotionalism.'” I don’t think he picked the phrase up; he breathed it in with the Egham air. He was also not religious by nature: “With Cyril Connolly,…I believed in the Either, the Or and the Holy Both.” But he was loyal to his family, his community, and, above all, to his beloved observant father:

To have made a clean break with Judaism would have felt like making a clean break with myself. Wavering became a way of life, and by the age of eighteen I had settled, or seemed to have settled, for a world of token observance and demisemi-belief.

This two-way pull between the religion he didn’t believe in and the life he was making for himself is the central theme of Gross’s book. Why faith, or his lack of it, should still vex him so much in this secular society is a tricky question, but, for Gross, the answer is clear:

For many Jews, whatever the larger historical balance sheet, anti-Semitism is the heart of the matter, the only significant reason why they still feel Jewish. For all Jews, inevitably, having to take account of it represents “the last attachment’: discard religion, cut your communal ties, and prejudice is still liable to turn up at the feast. But to have had a religious upbringing at least ensures that in your own mind you are a Jew first, and the object of other people’s dislike second. And after that—well, it has been said that to be Jewish is to belong to a club from which no one is allowed to resign.

Gross tells his story reticently and modestly, a style Endelman might interpret as a typically Anglo-Jewish way of dealing with the society around him. As Endelman sees it, England’s “genteel intolerance” emasculated the Jews, gnawed away at their collective identity, and kept them on the margins of Jewish intellectual life. As a result, Judaism in Britain was steadily diluted in the ambient gentility, until the Holocaust and then the foundation of the state of Israel gave British Jews a cause to rally around. They still do, though how long that new sense of identity will last is not certain. Fifty years ago, fashionable Marxists yearned for, and laid claim to, working-class credentials they did not have. Since the fall of communism, ethnicity has replaced Marxism, and what Ian Buruma calls “sentimental solidarity” has shifted from the proletariat to the world of the grandfathers.

As a historian, Endelman has a low opinion of English contributions to Jewish scholarship and sectarian debate, and that leads him to harsh conclusions about “the intellectual poverty of Anglo-Jewry…and the cultural barrenness of the Anglo-Jewish landscape.” The two issues seem less clearly related in Great Britain than Endelman thinks. For the last three centuries, more or less since the Jews resettled in England, intellectuals of all denominations have usually steered clear of religion; and we have the declining Church of England to prove it. But secular intellectual life in Britain is by no means poverty-stricken, and gifted English Jews like Gross, by coming at it from a skewed angle, with a different load of prejudices on their backs, have helped to change it just as profoundly as England changed them.

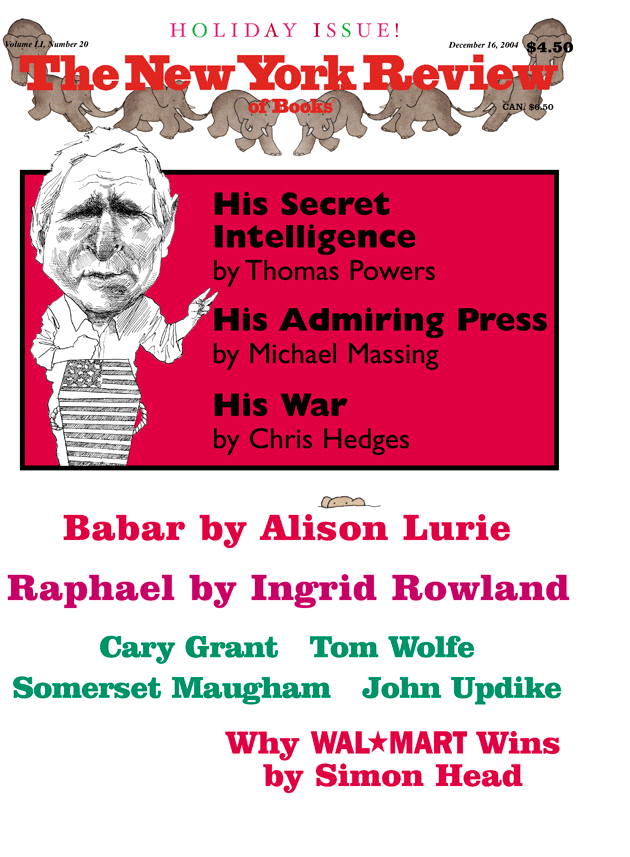

This Issue

December 16, 2004

-

1

Endelman is quoting a petition sent to Sir Thomas Fairfax, whose daughter Mary was tutored by Andrew Marvell. It adds a topical edge to the lines, “And you should, if you please, refuse/ Till the conversion of the Jews.” ↩

-

2

Ian Buruma, Anglomania: A European Love Affair (Random House, 1998), p. 299. ↩

-

3

This reaction was not confined to England. The dismay of middle-class Central European Jews confronted by Orthodox Ost-Juden is a recurrent theme in the work of the Austrian-born Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld. I imagine Muslim fundamentalists have a similar effect now on their acculturated brethren. ↩