When Amos Oz’s moving and frank autobiography—partly family saga, partly Bildungsroman, partly self-portrait—was first published in Israel two years ago, it was praised as his finest book so far. In a review in Haaretz, the novelist Batya Gur drew attention to the illustration on the cover of the Israeli edition: Pablo Picasso’s 1903 painting, now at the National Gallery in Washington, entitled Tragedy. Three barefoot figures are seen stranded on a desolate, pale-blue beach: a gaunt man and woman with sagging heads and a small child. The man and the woman avoid facing each other, their arms are crossed in a gesture of loneliness and alienation. The child is lightly touching the man’s thigh in what seems a desperate attempt to make contact.

One can imagine Oz identifying with that child. He grew up as a lonely boy, the son of unhappy, ill-matched parents. He taught himself to read and write when he was five and then read a book, and sometimes two, almost every day. His autobiography concentrates on the private tragedy of his mother’s suicide and at the same time, as Gur puts it, it also reflects upon a greater national tragedy, the troubled, disappointed lives of European Jews who, like Oz’s parents and grandparents, escaped in time to the Promised Land but never found there what they expected. Instead of tranquillity and peace they lived in an atmosphere of endless war. This may have happened anyway, but in my view it may have been largely caused by the shortsightedness of successive Israeli leaders and their indifference to the fate of the Palestinians, and by the moral blindness that marks practically all ethnocentric movements.

This is a sad book, a tale of twisted lives and stunted hopes. The Eurocentric prejudices of Oz’s grandmother provide a few moments of comic relief; she was so obsessed with the “germs” infecting everybody and everything in the Levant that she took three hot baths a day and forced her husband to shake out the carpets twice a day. Oz powerfully evokes the sounds and sights of the 1940s but we hear none of the clichés about heroic young men and women, silent, thoughtful, and self-disciplined, fighting for independence and making the desert bloom in remote outposts. Instead we are among the confused, largely destitute, dislocated city people who made up most of the Jewish population. His father is tortured by his failures to make a decent living; his mother is depressed because she feels poor and is in failing health. We meet other uprooted middle-class businessmen and professionals who have also become poor through emigrating to an underdeveloped country.

Oz has much to say about their sometimes bizarre politics and he describes certain proto-fascist intellectuals, dismissed or ridiculed at the time as marginal, but harbingers of things to come. Rowdy young men march through the streets dressed in brown shirts, chanting “In blood and fire Judea fell, in blood and fire it will rise again.” Some of them demand that Palestinian Arabs be expelled and sent to Syria and Egypt. Amos’s great-uncle Joseph Klausner, a leading right-wing ideologue and advocate of a Greater Israel on both sides of the Jordan, called on Jews with Napoleonic fervor, Oz writes, to become like all other nations, hard like iron, ruthless “lions among other lions.”

Against the background of intermittent war in Jerusalem, Oz dissects the private tragedy that, as we now learn for the first time, has haunted his entire life and indirectly shaped some of the characters of his novels and short stories. The reader soon becomes aware that he is peeling away layer after layer of a long-repressed, painful past. He was born in 1939 in Jerusalem, in a damp, low-ceilinged, one-room basement apartment crammed with books in sixteen languages, to Arieh and Fania Klausner, recent immigrants from eastern Poland who spoke, in a Russian accent, nearly all the languages in the books they owned. A tiny opening in the back wall of the narrow kitchenette looked out onto a small cement yard surrounded by high walls where “a pale geranium…was gradually dying for want of a single ray of sunlight.”

The Kerem Avraham (or Abraham’s Vineyard) section of Jerusalem where they lived was at one end of town, far away from fashionable neighborhoods where British colonial officials and Zionist politicians lived, along with the top bureaucrats and professors at the new university, and learned refugees from Weimar Germany who gathered regularly in apartments for musical soirees and German poetry readings.

The streets in Kerem Avraham were still unpaved, littered with rubbish, rusty sheets of tin, and discarded building materials. The people in the neighborhood were mostly recent immigrants like his parents, grade school teachers, lowly clerks at the various semi-independent Zionist institutions, trade union officials, artisans, and small retailers. They were all convinced of the need for Jews to return to a “new life” of agriculture and manual labor in their own country, even though they themselves remained office workers and shopkeepers. There were right-wingers and left-wingers; some were believers, some were atheists, but hardly any were ultra-Orthodox. They read many newspapers, as well as pamphlets and party manifestoes. To the young Oz, the people in the neighborhood seemed consumed by ideas, whether about socialism, the causes of anti-Semitism, the “agrarian question,” or the “Arab question”:

Advertisement

As a child I could only dimly sense a gulf between their enthusiastic desire to reform the world and the way they fidgeted with the brims of their hats when they were offered a glass of tea, or the terrible embarrassment that reddened their cheeks when my mother bent over (just a little) to sugar their tea and her decorous neckline revealed a tiny bit more flesh than usual: the confusion of their fingers, which tried to curl into themselves and stop being fingers. All this was straight out of Chekhov.

His parents, Oz writes, had come to Jerusalem “straight from the nineteenth century,” the Europe of Ga-ribaldi, Mickiewicz, Parnell, and the “Spring of Nations.” In Jerusalem they found political uncertainty, war, ethnic strife, heat waves, and poverty. Many among them retained an inchoate yearning for the Europe of Homer, Goethe, Shakespeare, Chekhov, and Tolstoy,

a forbidden promised land…of belfries and squares paved with ancient flagstones, of trams and bridges and church spires, remote villages, spa towns, forests, and snow-covered meadows.

The father, Arieh Klausner, had grown up on a concentrated diet of “operatic, nationalistic, battle-thirsty romanticism.” He was a “right-wing” Zionist, a minority at a time when most members of the Jewish community of Palestine espoused socialist and cooperativist ideas and spoke of, or at least paid lip service to, a need to compromise with the Palestinians. He sympathized with the brown shirts of Betar, a paramilitary youth movement founded by the “revisionist” leader, the poet-politician Vladimir Jabotinsky—the author of the slogan I have quoted: “In blood and fire Judea fell, in blood and fire it will rise again”—whom the British had exiled from Palestine for advocating the establishment of a Jewish state on both sides of the river Jordan by force of arms. The father loathed Ben-Gurion’s dominant Zionist faction for its collectivist experiments in cooperatives and kibbutzim and for what he took to be the cowardly subservience of the Zionist leaders to their British overlords. Only Amos’s mother once remarked about the British, “Who knows if we won’t miss them soon.”

The parents were incompatible, and both were miserable. The mother was a moody, imaginative dreamer. The father was a dry pedant, a walking dictionary unable to have close relations either with his wife or his child, whose birth may have been unwanted. He would joke in his rather anemic way, Oz remembers, that the world was not a fit place in which to have children. In saying this, Oz writes, he seemed to be uttering an implied reproach to Oz for being born so recklessly and irresponsibly. One of the few occasions when his father actually hugged him was on the night in 1947 when the General Assembly of the UN voted to establish a Jewish state, the only time, it seems, when he saw tears in his father’s eyes. “From now on,” said his father, “from the moment we have our own state, you’ll never be bullied just because you are a Jew.”

The father was embittered by his failure to secure an academic post in a Jerusalem where, in the late 1930s, there were said to be more refugee professors than students. A graduate of both Vilna University in Lithuania and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, he made a meager living as a librarian. Occasionally he had to sell one of his precious books to provide the family a decent Sabbath meal. He was a self-centered, prudish man, learned in many fields, filled with suppressed discontent, unable to talk about what hurt him. The awkward silences in the family were camouflaged by displays of learning and tiresome reconstructions of the etymological roots of Hebrew words from Greek, Latin, French, and Chaldaean, and by limp academic jokes:

If my mother said, for instance, that our neighbor Mr. Lemberg had come back from the hospital looking more emaciated than when he went in and they said he was in dire straits, Father would launch into a little lecture on the origin and meaning of the words “dire” and “straits,” replete with biblical quotations. Mother expressed amazement that everything, even Mr. Lemberg’s serious illness, sparked off his childish pleasantries. Did he really imagine that life was just some kind of school picnic or stag party, with jokes and clever remarks? Father would weigh her reproach, apologize, but he had meant well, and what good would it do Mr. Lemberg if we started mourning for him while he was still alive? Mother said, Even when you mean well, you somehow manage to do it with poor taste: either you’re condescending or you’re obsequious, and either way you always have to crack jokes. At which they would switch to Russian and talk in subdued tones.

Amos was a precocious, moody child surrounded by learned if slightly pompous adults, with few if any playmates his own age. His father, aware of his gifts, tended to show him off but sardonically called him “His Highness” or “Your Honor.” “His Highness will once again be compelled to suffer the consequences of his deeds. I am sorry.”

Advertisement

The mother, Fania (née Mussman), was a native of Rovno in eastern Poland, a lakeside city with a romantic skyline dominated by a citadel and Catholic and Orthodox churches. Rovno was a mixed city of Poles and Russians, in which Jews made up the majority. She was a graduate of a Tarbuth gymnasium, one of a group of elite Hebrew high schools in Eastern Europe that offered, in addition to the mandatory state curriculum, a rich program of Jewish philosophy, ancient and modern Hebrew writers, and readings, in Hebrew translation, of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, Turgenev, Chekhov, Mickiewicz, Schiller, Goethe, Heine, Shakespeare, Byron, Dickens, Jack London, and Knut Hamsun. She was the daughter of well-to-do parents, and grew up in a mansion attended by servants and cooks, a gardener and a coachman. Life in the miserable Kerem Avraham quarter must have been especially hard on her. She had few friends and was shut up at home for most of the time.

She was an imaginative woman who told Amos tales of faraway forests and snow-covered meadows teeming with fantastic creatures and ghosts, men so old that moss grew out of their backs and brown roots sprouted from their feet. He would fall asleep to the sound of northern, icy winds shrieking in great open chimneys, sounds he had never heard, chimneys he had never seen. In the cold Jerusalem winters the Klausners’ apartment was hardly warmed by a single small spiral electric heater.

Fania suffered from chronic, seemingly incurable, bouts of depression that began with severe headaches. Her movements slowed, and she became absent-minded. Amos and his father kept asking her, “Are you all right? Are you all right?” The slightest disturbance made her start. As Amos grew older she deteriorated further. Her migraines and insomnia grew worse, and she spent entire days and even nights staring out of the narrow window. It was the only period when Amos and his father became close, “like a pair of stretcher bearers carrying an injured person up a steep slope.” Fania neglected housework and was tended by Amos and her husband like a child. She all but stopped eating. The descriptions of her gradual decline are among the more harrowing in this memoir.

She committed suicide three months before Amos’s bar mitzvah. He was not allowed to attend her funeral. “She died of disappointment or longing,” Oz wrote years ago. Her parents and sisters accused Arieh of having driven her to her death. After his mother’s suicide, the boy’s schoolwork went downhill. One year after her death his father remarried. There had long been another woman in his life. After this Amos left home. He wanted to get away, once and for all, from Jerusalem, with all it stood for, its history, its politics, his father. At age fifteen, in defiance of his father who saw the kibbutz movement as a threat to the national ethos, if not an extension of Stalinism, he joined the kibbutz Hulda, changing his surname to Oz (strength, in Hebrew). “I killed my father…. I killed him particularly by changing my name,” he writes.

Amos lived in the kibbutz for over thirty years. During the next twenty years, before his father died, they met rarely and never talked about his mother’s death. “Not a word. As if she had never lived.” On one occasion the father visited him and told one of his fellow kibbutzniks that he was grateful for what they were doing for his son. Then, “like someone collecting a dog from a boarding kennel,” he added: “He was rather out of condition in some ways when he came, and now he seems in tip-top form.”

In his early teens, before he left home, Amos had been a “fiercely nationalistic child,” fully sharing his family’s wish for Jews to become “lions” among the other lions. “If we aspire to be a people ruling over our own land,” his father said, “then our children must be made of iron.” During the declining years of British rule, Amos admired the terrorists of the Stern Gang and Menahem Begin’s Irgun Zvai Leumi, whose members blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing more than eighty Britons, Arabs, and Jews. They also killed Lord Moyne, the British war cabinet minister resident in Cairo, and hanged British army sergeants in reprisals for the hanging of Jewish terrorists. Sitting on the kitchen floor, Amos had his toy soldiers attack Government House and drew up plans to fire long-range missiles at Buckingham Palace. On the eve of his flight to the kibbutz he suddenly freed himself from his father’s politics.

Ironically, it was his chief idol, Begin himself, who caused him to change. After independence in 1948, with Israel in only partial control of Palestine, Begin had emerged from the underground and was running for the Knesset on a platform that still demanded a Greater Israel on both sides of the river Jordan. At a rally at Edison Hall, Jerusalem’s largest auditorium, Amos sat in one of the front rows between his father and his grandfather, and next to other like-minded followers of the far right.

Most of the leading right-wing politicians as well as Begin himself spoke the perfect, classic Hebrew that they had learned out of books or in one of the Tarbuth gymnasiums in Eastern Europe, while those sitting further back in the large hall, mostly working-class immigrants from Middle Eastern countries, used colloquial street Hebrew. Begin, a great orator, was attacking the readiness of the great powers to arm the Arabs. In biblical Hebrew, but not in the Jerusalem vernacular, the same word was used at the time for “weapon” and the male sexual organ. In the vernacular, the verb “to arm” was the same as “to fuck.”

In rising, melodious cadences Begin was, for most of those present, complaining that Eisenhower and Anthony Eden were “fucking” Nasser day and night. But who is fucking us? he asked in an outraged voice. “Nobody! Absolutely nobody!” A stunned silence filled the hall. Begin did not notice. He went on to predict that if he were to become prime minister everyone would be fucking Israel. Faint applause rose from the elderly intellectuals in the first three rows. Behind them, unable to believe their ears, the large crowd remained uneasily silent. Only one twelve-year-old, until this moment a devoted Beginite, could not contain himself and burst out laughing. Horrified looks were fixed upon Amos from all sides. In a rage, his grandfather pulled him from his seat and dragged him out by his ear; Amos was still choking with laughter. Outside, his grandfather finally silenced him by furiously slapping him on his cheeks. Citing his great-uncle’s autobiography, My Road to Resurrection and Redemption, Oz writes that at that very moment he first started to run away from the resurrection and redemption espoused by Begin’s nationalists. He adds: “I am still running.”

On a sunny spring morning many years ago, Amos Oz, then in his early thirties, and I were walking through the Kerem Avraham quarter in northwestern Jerusalem where Oz had grown up. It was a year or two after the victory of the Six-Day War. Oz had been one of the few to warn against the prevailing hubris and the annexation of occupied territory. He had scandalized many by publicly declaring that in the occupied Palestinian part of Jerusalem he had felt as if he were in a foreign city.

The quarter was much changed. It was now almost taken over by the ultra-Orthodox with their large families and many children. A good number of the old houses still stood but the few trees and bushes that had once grown in the narrow spaces between the stone walls had disappeared under a clutter of zinc-covered sheds and shacks that had been enlarged with additions in tin, wood, or brick, in violation of building codes that were rarely enforced. We paused outside his dilapidated old house. Looking around, I could not help telling him that while much had changed, Kerem Avraham could not have been very much more agreeable in the old days. “All this does not count,” Oz said with a wan smile, “it’s only the first draft.” He had more in mind than urban decay, as his political activities and some of his subsequent books have shown, notably the essays in In the Land of Israel: he was, it now seems clear, referring to the dire need to change course and try again.

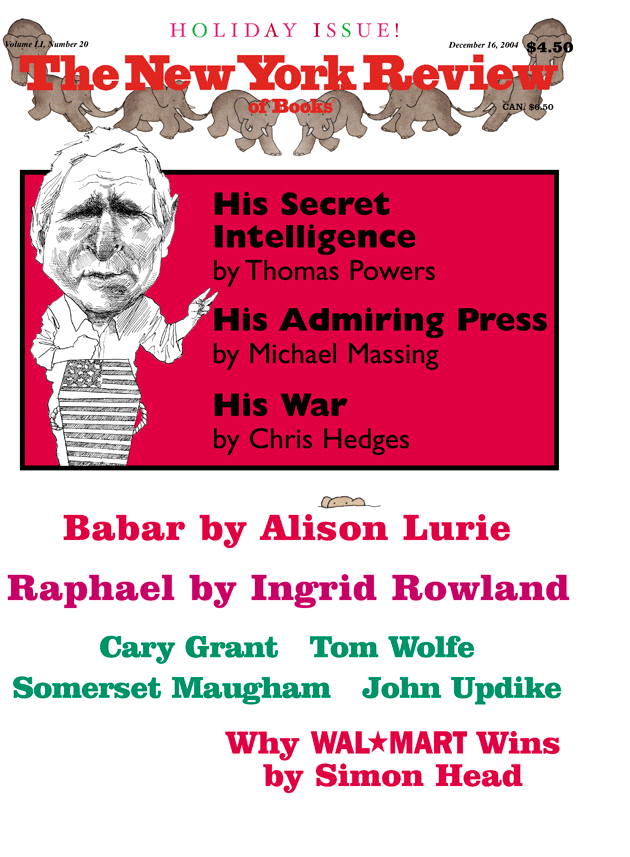

This Issue

December 16, 2004