1.

The vanquished know war. They see through the empty jingoism of those who use the abstract words of glory, honor, and patriotism to mask the cries of the wounded, the senseless killing, war profiteering, and chest-pounding grief. They know the lies the victors often do not acknowledge, the lies covered up in stately war memorials and mythic war narratives, filled with stories of courage and comradeship. They know the lies that permeate the thick, self-important memoirs by amoral statesmen who make wars but do not know war. The vanquished know the essence of war—death. They grasp that war is necrophilia. They see that war is a state of almost pure sin with its goals of hatred and destruction. They know how war fosters alienation, leads inevitably to nihilism, and is a turning away from the sanctity and preservation of life. All other narratives about war too easily fall prey to the allure and seductiveness of violence, as well as the attraction of the godlike power that comes with the license to kill with impunity.

But the words of the vanquished come later, sometimes long after the war, when grown men and women unpack the suffering they endured as children, what it was like to see their mother or father killed or taken away, or what it was like to lose their homes, their community, their security, and be discarded as human refuse. But by then few listen. The truth about war comes out, but usually too late. We are assured by the war-makers that these stories have no bearing on the glorious violent enterprise the nation is about to inaugurate. And, lapping up the myth of war and its sense of empowerment, we prefer not to look.

The current books about the war in Iraq do not uncover the pathology of war. We see the war from the perspective of the troops who fight the war or the equally skewed perspective of the foreign reporters, holed up in hotels, hemmed in by drivers and translators and official minders. There are moments when war’s face appears to these voyeurs and killers, perhaps from the back seat of a car where a small child, her brains oozing out of her head, lies dying, but mostly it remains hidden. And the books on the war in Iraq have to be viewed, through no fault of the reporters, as lacking the sweep and depth that will come one day, perhaps years from now, when a small Iraqi boy or girl reaches adulthood and unfolds for us the sad and tragic story of the invasion and bloody occupation of their nation.

War is presented primarily through the distorted prism of the occupiers. The embedded reporters, dependent on the military for food and transportation as well as security, have a natural and understandable tendency, one I have myself felt, to protect those who are protecting them. They are not allowed to report outside of the unit and are, in effect, captives. They have no relationships with the victims, essential to all balanced reporting of conflicts, but only with the Marines and soldiers who drive through desolate mud-walled towns and pump grenades and machine-gun bullets into houses, leaving scores of nameless dead and wounded in their wake. The reporters admire and laud these fighters for their physical courage. They feel protected as well by the jet fighters and heavy artillery and throaty rattle of machine guns. And the reporting, even among those who struggle to keep some distance, usually descends into a shameful cheerleading.

Those who cover war dine out on the myth about war and the myth about themselves as war correspondents. Yes, they say, it is horrible, and dirty and ugly; for many of them it is also glamorous and exciting and empowering. They look out from the windows of Humvees for a few seconds at Iraqi families, cowering in fear, and only rarely see the effects of the firepower. When they are forced to examine what bullets, grenades, and shells do to human bodies they turn away in disgust or resort to black humor to dehumanize the corpses. They cannot stay long, in any event, since they must leave the depressing scene behind for the next mission. The tragedy is replaced, as it is for us at home who watch it on television screens, by a light moment or another story. It becomes easier to forget that another human life has been ruined beyond repair, that what is unfolding is not only tragic for tens of thousands of Iraqis but for the United States.

The other distorted prism into this war came to us, until the occupation, courtesy of the oily functionaries at the Iraqi Ministry of Information. The regime of Saddam Hussein controlled journalists as tightly as the US military does. The reporting from the bowels of the regime was often characterized by innuendo and inference. This reporting of the war, because reporters were so heavily circumscribed, turned their attention onto their own minor privations and the lives of their drivers, translators, and the narrow circles within the ruling elite that were permitted to speak with them.

Advertisement

There is uniformity about journalistic war memoirs reaching all the way back to Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, although I confess I enjoy reading them. But they violate every rule of serious reporting. It is an unwritten rule, for example, among foreign correspondents that no matter how good the quote, you do not interview taxi drivers, translators, or bartenders. You leave these interviews to the hacks who parachute into a war zone, ride nervously to the hotel, sit at the bar, go to the embassy or UN background briefing, and fly swiftly home. But in a world where it is impossible to do much more than get on the official bus for the official tour and go to the official briefing, taxi drivers and bartenders offer in places like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq refreshing and candid perspectives when set against the absurdity of official prop- aganda. At a certain point, as Waugh realized, these experiences can only be written as farce.

Generation Kill: Devil Dogs, Iceman, Captain America and the New Face of American War by Evan Wright is an account of the invasion by a reporter embedded with the Marines. It is a much better book than the title would indicate—not to mention the cover art of a grim solder in desert camouflage with an assault rifle, and the ridiculous excerpt on the back, a near parody of me-as-hero war reporting: Wright gave up his satellite phone, unlike his colleagues in the electronic media, who replaced reporting with a breathless play-by-play description of what their cameras were showing viewers from the battlefield. He followed a Marine battalion for six weeks from Kuwait to Baghdad. As he admits himself, his book suffers from his rarely having been around long enough to find out what the tremendous and by his own observation often indiscriminate firepower did to the hapless Iraqi families within the range of the guns, artillery, and fighter jets. But the anecdotal evidence, including the obliteration of villages where there was no serious resistance, along with isolated incidents where the unit had to stop and tend the children and civilians they wounded or killed, mounts by the end of the book to present a withering indictment of the needless brutality of the invasion.

He writes toward the conclusion of his narrative:

In the past six weeks, I have been on hand while this comparatively small unit of Marines has killed quite a few people. I personally saw three civilians shot, one of them fatally with a bullet in the eye. These were just the tip of the iceberg. The Marines killed dozens, if not hundreds, in combat through direct fire and through repeated, at times almost indiscriminate, artillery strikes. And no one will probably ever know how many died from the approximately 30,000 pounds of bombs First Recon ordered dropped from aircraft.

The reason wars should always be covered from the perspective of the common soldier or Marine, as Wright does, is that these foot soldiers are largely pawns. Their lives, despite the protestations of the generals and politicians, mean little to the war planners. Officers who put the safety of their men before the efficiency of the war machine are usually viewed as compromised. Wright, by writing about one conscientious officer, Lieutenant Nathaniel Fick, who at times defies orders that he believes will get his men killed needlessly, shows us the raw meat grinder at the core of the military, how it pushes aside all those who do not offer up the soldiers under their command to the god of war.

Physical courage is common on a battlefield. Moral courage is not. Those who defy the machine usually become its victim. And Lieutenant Fick, who we find in the epilogue has left the Marines to go back to school, wonders if he was a good officer or if his concern for his men colored his judgment. Those who make war betray those who fight it. This is something most enlisted combat veterans soon understand. They have little love for officers, tolerating the good ones and hoping the bad ones are replaced or injured before they get them killed. Those on the bottom rung of the military pay the price for their commanders’ vanity, ego, and thirst for recognition. These motives are hardly exclusive to the neocons and the ambitious generals in the Bush administration. They are a staple of war. Homer wrote about all of them in The Iliad as did Norman Mailer in The Naked and the Dead. Stupidity and callousness cause senseless death and wanton destruction. That being a good human being—that possessing not only physical courage but moral courage—is detrimental in a commander says much about the industrial slaughter that is war.

Advertisement

Combat has an undeniable attraction. It is seductive and exciting, and it is ultimately addictive. The young soldiers, trained well enough to be disciplined but encouraged to maintain their naive adolescent belief in invulnerability, have in wartime more power at their fingertips than they will ever have again. From being minimum-wage employees at places like Burger King, looking forward to a life of dead-end jobs, they catapult to being part of, in the words of the Marines, “the greatest fighting force on the face of the earth.” The disparity between what they were and what they have become is breathtaking, intoxicating. Their intoxication is only heightened in wartime when all taboos are broken. Murder goes unpunished and is often rewarded. The thrill of destruction fills their days with wild adrenaline highs, strange grotesque landscapes that are almost hallucinogenic, and a sense of purpose and belonging that overpowers the feeling of alienation many left behind. They become accustomed to killing, carrying out acts of slaughter with no more forethought than they take to relieve themselves. Wright describes the end of a day of battle:

By five o’clock in the afternoon, the Iraqis who had earlier put up determined-though-inept resistance have either fled or been slaughtered. Colbert’s team, along with the rest of the platoon, speeds up the road toward the outskirts of Baqubah. Headless corpses—indicating well-aimed shots from high-caliber weapons—are sprawled out in trenches by the road. Others are charred beyond recognition, still sitting at the wheels of burned, skeletized trucks. Some of the smoking wreckage emits the odor of barbecuing chicken—the smell of slow-roasting human corpses inside. An LAV rolling a few meters in front of us stops by a shot-up Toyota pickup truck. A man inside appears to be moving. A Marine jumps out of the LAV, walks over to the pickup truck, sticks his rifle through the passenger window and sprays the inside of the vehicle with machine-gun fire.

Those who carry out this killing will pay a terrible price. As the unit approaches Baghdad they become weary with the indiscriminate shooting of unarmed Iraqis, including families that drive too close to roadblocks. Wright notes that “…the enlisted Marines, tired of shooting unarmed civilians, fought to be allowed to use smoke grenades.” Many of these young men will never sleep well for the rest of their lives. Most will harbor within themselves corrosive feelings of self-loathing and regret. They will struggle with an unbridgeable alienation when they return home, something Evans sees glimpses of in the final pages of the book.

These Marines have learned the awful truth about our civil religion. They have learned that our nation is not righteous. They have understood that there are no transcendent goals at the heart of our political process. The Sunday School God that blesses our nation above all others vanishes in war zones like Iraq. These young troops disdain the teachers, religious authorities, and government officials who feed them these lies. This is why so many combat veterans hate military shrinks and chaplains, whose task is largely to patch them up with the old clichés and ship them back to the battlefield. It is why they feel distance and anger with those at home who drink in the dark elixir of blind patriotism, and absorb mythology about themselves and war.

One of the Marines in the book returns to California and is invited to be the guest of honor in a gated community in Malibu, a place where he could never afford to live. The residents want to toast him as a war hero.

“I’m not a hero,” he tells the guests. “Guys like me are just a necessary part of things. To maintain this way of life in a fine community like this, you need psychos like us to go out and drop a bomb on somebody’s house.”

But these veterans will also miss war. They will miss it because at the height of the killing they can ignore the consequences. They will miss having comrades, whom they mistake for friends, comrades who at the time seem closer to them than their families. They will miss the brief, unfettered moment when they were killer gods and everyone around them fighting a common enemy, and facing death as a group, seemed fused into one body. “They like this part of war,” Wright correctly writes of the comradeship, “being a small band out here alone in enemy territory, everyone focused on the common purpose of staying alive and killing, if necessary.”

The end of war is cruel, for these comrades again become strangers. Those who return are forced to face their demons. They must fall back onto the difficult terrain of life on their own. Wartime comradeship is about the suppression of self-awareness, self-possession, and self-understanding. This is part of its allure, the reason people miss it and seek years later, often with the aid of alcohol, to recreate it. But outside of war the camaraderie does not return. These young men and women are sent home to a nation they see in a new light. They struggle with the awful memories and trauma and are shunted aside unless they are willing to read from the patriotic script handed to them by the mythmakers. Some do this, but most cannot.

Wright, because he reports from the perspective of the enlisted Marines, sees the bizarre subculture of the military. He watches the chaos of war, the way it never turns out as planned and how it opens up a Pandora’s box that gives war a life and power beyond anyone’s control. He notes the incompetence and callousness of many senior officers who send their men into minefields at night or up against superior forces to burnish their own reputations as warriors. He understands the way killing in war, which always includes murder, slowly eats away at soldiers and Marines.

Given the severe limitations of seeing war through the eyes of the killers, his book is nevertheless sensitive, thoughtful, nuanced, and he is able, because of his honesty, to capture the sickness and perversion of the battlefield. Generation Kill reminds me of Jarhead by Anthony Swofford, although Swofford was able to add a crucial layer of distance, allowing us to see how the enterprise of killing had over time maimed him and those he served with in the 1991 Gulf War. But as war memoirs go this one is first-rate, as long as we remember that it is a portrait of warriors, not war.

2.

While Wright was making his way toward Baghdad from southern Iraq with the Marines, Jon Lee Anderson was in the Iraqi capital for The New Yorker. Anderson spent his days trying to free himself, if only for a few minutes, from the iron Iraqi control. He was hampered in his work by government minders, constant surveillance, restrictions on where he could go, whom he could see, and what he could write. This kind of reporting swiftly becomes a reporting of nuance, a reporting where truth is seen in shadows and reflections, in hasty whispers and wayward looks. Reporters and photographers pay a heavy price for this control. They must accept becoming reluctant tools of those in power. Indeed, when, in Anderson’s book The Fall of Baghdad, someone asks the Iraqi official Muhammad al-Sahaf how his Information Ministry will continue to function after it has been destroyed by American warheads, he replies: “You are the Ministry of Information.”

The difficult conditions under which Anderson worked meant that the usual standards of reporting had to be relaxed. Reporters were in many ways hostages of the Iraqi regime, trotted out when the regime wanted to get across a message and locked up the remainder of the time. The best reporters, such as Anderson or the New York Times correspondent John Burns, were masters at slipping in enough details and writing with enough irony to remind us where they were reporting from. But I am not sure their work can be considered great reporting.

“A crowd of journalists milled around confusedly and began piling on board a couple of buses,” Anderson writes of his reporting experience during the invasion.

I hopped on one of them. Invariably these trips, laid on by the ministry, were inspection tours of freshly bombed sites involving civilian targets; it had become a daily ritual since the war began. We were never shown any damage done to military installations or to buildings in the presidential complex.

Anderson had to struggle, as did all who reported from Saddam Hussein’s repressive state, with the usual mouthing of clichés by frightened citizens and functionaries who memorized opinions to ensure their self-preservation. He clutters up some of his book, especially the beginning when he allows people to speculate about a looming war, with a tiring recitation of official government lines and disinformation. But once the narrative gets underway with the first night of the bombing of Baghdad, he writes movingly about a defenseless country that is rapidly overpowered by a superior and technologically advanced military giant.

He reminds us of the lopsidedness of the war, something painfully apparent to Iraqis and perhaps not always appreciated by those who were embedded with the invading force. American and British fighter jets had total control of the skies and carried out air strikes with few losses and little more than desultory antiaircraft fire. Anderson, through his own blunders, quickly uncovers the humiliation Iraqis feel, a humiliation that, even though they hate the dictator, sees them rejoice in the supposed downing of an American jet or the crippling of an American tank. The abject humiliation endured at the hands of the invading Americans goes a long way toward explaining the virulence of the current armed resistance to the occupation.

Anderson has a sensitivity that saves his book from being, like so many war memoirs, voyeurism. He keeps to a minimum the pornographic images of violence and deprivation. He manages to write with empathy about ordinary Iraqis, who deserved neither Saddam Hussein nor the Americans. Although the Iraqis he follows are confined largely to the elite or the small staff who work for him, he nevertheless puts a human face on the suffering endured by those on the other end of our weapons systems. The privations of the Iraqis, of whom as many as 100,000 may by now have been killed in the invasion and occupation, is something that few of us saw during the war, although horrifying images were disseminated through the Arab networks such as al-Jazeera. Such images make it hard to sell the enterprise of war or boost the circulation of newspapers or the ratings of cable news channels that use the myth of war to attract viewers or readers. This mythic narrative of war is what most at home desire to see and hear. The reality of war is so revolting and horrifying that if we did see war it would be hard for us to wage it.

Anderson visits Iraqi hospitals as the war goes on. These visits were required trips on the staple Iraqi propaganda tour ever since the sanctions were imposed after the first Gulf War. Nevertheless, the scenes in the hospital corridors in The Fall of Baghdad are a reminder that this war, despite the assurances of the Bush administration, was neither clean nor precise. Tens of thousands of innocent Iraqis have been wounded and killed. Anderson, by focusing on a few victims, including two children, helps to counter the glib excuses for the war. He stands in a hospital looking at the body of a small child killed by American bombs, and the image alone mocks all those who promoted the war on humanitarian grounds:

Before the cloth covered her, I saw that the girl was covered in blood. Her brother looked as though he were sleeping. But they both were dead. Their mother was there, beside herself with grief. She was the woman I had heard wailing and hitting the walls. Then almost all the onlookers around the mother, including the doctors and nurses, broke down and cried. I was overcome and went outside and sat down. I wept. The children’s father was sitting a few feet away from me, disconsolately sobbing into his arms.

Reporters who accept being herded around by minders, Iraqi or American, and are spoonfed stories are a necessary part of the landscape in war. They give us a feel, however circumscribed, for minute acts of folly and brutality. But these reporters are often the least equipped to deal with the broader moral and political questions about war. They are swallowed up by systems, whether of dictatorships or of the military. They must write stories that do not antagonize their handlers and get them expelled from the unit or the country they cover. They become masters at self-censorship, knowing how far they can inch forward their reporting. But these skills cripple them. They have spent too long being compromised.

Wright and Anderson have given us a diary-like reporting of the war that illustrates day to day what a few of the elite units, whether American or Iraqi, endured. They do this well. They are intelligent and sensitive. Some of the passages in their books are moving. They resist the narcissism that often infects such accounts of war. But at the same time the books, given the moral and political morass gripping the United States, have a frightening moral neutrality. The writers do not grasp, because they cannot feel it, the red-hot rage, the utter humiliation and indignation that have pushed Iraqis to turn their country into an inferno. Wright backs away from the utter perversion that grips the life of heavily armed Marines allowed to blast their way through Iraqi villages.

These writers can, at times, evoke pity and compassion for some of the people who suffer from the effects of the war, but they do not confront what war does to societies and individuals, what it has done to Iraq and to us. War, after all, is not a natural disaster like earthquakes or typhoons. It is a devastating and violent attempt at large-scale social engineering. It changes the landscape and the lives of the occupiers and the occupied. We face a seismic political and moral upheaval. These books tell stories, often powerful stories, but in the end the writers cannot say what they mean.

We are losing the war in Iraq. There has been a steady increase in the assaults carried out by the insurgents against coalition forces. The attacks over the past year have risen from about twenty a day to approximately 120. We are an isolated and reviled nation. We are tyrants to others weaker than ourselves. We have lost sight of our democratic ideals. Thucydides wrote of Athens’ expanding empire and how this empire led it to become a tyrant abroad and then a tyrant at home. The tyranny Athens imposed on others it finally imposed on itself. If we do not confront our hubris and the lies told to justify the killing and mask the destruction carried out in our name in Iraq, if we do not grasp the moral corrosiveness of empire and occupation, if we continue to allow force and violence to be our primary form of communication, we will not so much defeat dictators like Saddam Hussein as become them.

—November 17, 2004

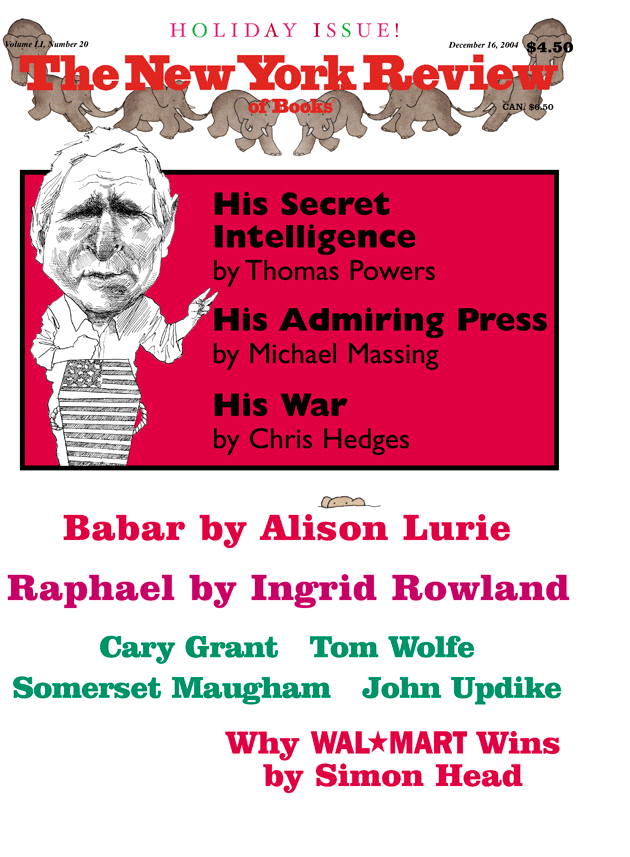

This Issue

December 16, 2004