On June 4, Jalal Talabani, president of Iraq, attended the inauguration of the Kurdistan National Assembly in Erbil, northern Iraq. Talabani, a Kurd, is not only the first-ever democratically elected head of state in Iraq, but in a country that traces its history back to the Garden of Eden, he is, as one friend observed, “the first freely chosen leader of this land since Adam was here alone.” While Kurds are enormously proud of his accomplishment, the flag of Iraq—the country Talabani heads—was noticeably absent from the inauguration ceremony, nor can it be found anyplace in Erbil, a city of one million that is the capital of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region.

Ann Bodine, the head of the American embassy office in Kirkuk, spoke at the ceremony, congratulating the newly minted parliamentarians, and affirming the US commitment to an Iraq that is, she said, “democratic, federal, pluralistic, and united.” The phrase evidently did not apply in Erbil. In their oath, the parliamentarians were asked to swear loyalty to the unity of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Many pointedly dropped the “of Iraq.”

The shortest speech was given by the head of the Iranian intelligence service in Erbil, a man known to the Kurds as Agha Panayi. Staring directly at Ms. Bodine, he said simply, “This is a great day. Throughout Iraq, the people we supported are in power.” He did not add “Thank you, George Bush.” The unstated was understood.

1.

When President Bush spoke to the nation on June 28, he did not mention Iran’s rising influence with the Shiite-led government in Baghdad. He did not point out that the two leading parties in the Shiite coalition are pursuing an Islamic state in which the rights of women and religious minorities will be sharply curtailed, and that this kind of regime is already being put into place in parts of Iraq controlled by these parties. Nor did he say anything about the almost unanimous desire of Kurdistan’s people for their own independent state.

Instead, President Bush depicted the struggle in Iraq as a battle between the freedom-loving Iraqi people and terrorists. Without the sacrifices of the American servicemen and -women, and the largesse of the US taxpayer, the terrorists could win. As Bush put it, “The only way our enemies can succeed is if we forget the lessons of September 11—if we abandon the Iraqi people to men like Zarqawi.”

Bush’s effort to revive the link between Iraq and September 11 produced a flood of criticism, leading some of his critics to dismiss him as a habitual liar on Iraq matters. Alas, the comment may be more indicative of how disconnected administration strategy is from the realities of Iraq. Unfortunately, many of the administration’s sharpest critics seem to share its assumption that there is a people sharing a common Iraqi identity, an inaccurate assumption that provides fodder for misleading Vietnam analogies.

There is, in fact, no Iraqi insurgency. There is a Sunni Arab insurgency. And it cannot win. Neither the al-Qaeda terrorists nor the former Baathists can win. Even if the US withdrew tomorrow, neither insurgents nor terrorists would be knocking down the gates to Iraq’s Presidential Palace in Baghdad.

Basically, the military equation in Iraq comes down to demographics. Sunni Arabs are no more than 20 percent of Iraq’s population. Even in Baghdad—once the seat of Sunni Arab power—Sunni Arabs are a minority. To succeed, the insurgency would have to win support from Iraq’s other major communities—the Kurds at 20 percent and the Shiites at between 55 and 60 percent. This cannot happen.

While the Kurds are mostly Sunni Muslims, they have a history of repression at the hands of Sunni Arabs. A few dozen Kurds have been involved in terrorist acts, but al-Qaeda and its allies have no support in the Kurdistan population, which is one reason Kurdistan has largely been spared the violence that has wracked Arab Iraq.

The Shiites are completely immune to any appeal by insurgents. Sunni fundamentalists consider Shiites as apostates, and possibly a more dangerous enemy than even the Americans. (The Americans, they know, will leave. The apostates want to rule.) For the last two years, Sunni Arab insurgents have targeted Shiite mosques, clerics, religious celebrations, and pilgrims—with a toll in the thousands. The insurgent goal is to provoke sectarian war, and they seem to be succeeding. In spite of calls for restraint by Shiite leaders, there are growing numbers of retaliatory killings of Sunni Arabs by Shiites.

But while the insurgents cannot win, neither can they be defeated.

For most of his thirty-five-year rule Saddam Hussein faced guerrilla warfare from Kurds or Shiites—and sometimes both. Even the most brutal of tactics could not pacify communities that did not accept Sunni Arab rule. Today Sunni Arabs reject rule by Iraq’s Shiite majority. It is unrealistic to think the American military—operating with a fraction of the intelligence of the Saddam Hussein regime and with much less brutality (Abu Ghraib notwithstanding)—can quell a Sunni Arab resistance that is no longer solely anti-American but also anti-Shiite.

Advertisement

2.

In his speech, President Bush outlined a two-pronged strategy for dealing with the insurgency: the training of Iraqi military and security forces to take over the fight (“As Iraqis stand up, we will stand down”) and the continuation of Iraq’s democratic transition with the writing of a constitution as its centerpiece.

Building national security institutions is a challenge in a country that does not have a shared national identity. Saddam’s army consisted of Sunni Arab officers (with a few exceptions) and Shiite and (until 1991) Kurdish conscripts. Today, the Iraqi military and security services are a mixture of Kurdish peshmerga, rehabilitated Sunni Arab officers from Saddam’s army, and Shiite and Sunni Arab recruits. What is little known is that virtually all of the effective fighting units in the new Iraqi military are in fact former Kurdish peshmerga. These units owe no loyalty to Iraq, and, if recalled by the Kurdistan government, they will all go north to fight for Kurdistan.

The Shiites, naturally, want a Shiite military that will be loyal to the new Shiite-dominated government. They have encouraged the Shiite militias—and notably the Badr Brigade—to take over security in the Shiite south, and to integrate themselves into the national military. Neither the Shiites nor the Kurds want the Sunni Arabs to have a significant part in the new Iraqi military or security services. They suspect—with good reason in many cases—that the Sunni Arabs in the military are in fact cooperating with the insurgency. No Kurdish minister in the national government uses Iraqi forces for his personal security, nor will any of them inform the Iraqi authorities of their movements. Instead, they entrust their lives to specially trained peshmerga brought to Baghdad. Many Shiite ministers use the Shiite militias in the same way.

A few months after the Iraqi elections, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld flew to Baghdad to warn the new Shiite-led government not to purge Sunni Arabs from the police and military. He got a promise, but the government has no intention of keeping on people associated with Saddam’s regime. Too many of them have the blood of Shiites or Kurds on their hands, and neither group is in a forgiving mood. But the Americans, with little comprehension of Iraq’s recent history, seem not to understand. Recently, the Kurds identified the retired Iraqi officer who personally carried out the 1983 execution of more than five thousand members of the tribe of the Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani. The killer’s son holds a senior security position in Iraq, appointed by the American occupation authorities.

3.

A Shiite list won a narrow majority in Iraq’s January elections. Sponsored by Iraq’s leading Shiite, Ali al-Sistani (himself an Iranian who was therefore ineligible to vote for his own list), the list includes Shiite religious parties, some secular Shiites including the one-time Pentagon favorite Ahmad Chalabi, and even a few Sunni Arabs. Real power in Shiite Iraq rests, however, with two religious parties: Abdel Aziz al-Hakim’s Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and the Dawa (“Call,” in English) of Iraq’s Prime Minister Ibrahim Jaafari. Of the two, SCIRI is the more pro-Iranian. Both parties have military wings, and SCIRI’s Badr Corps has grown significantly from the five thousand fighters that harassed Saddam’s regime from Iran in the decades before the war; it now works closely with Iraq’s Shiite interior minister, until recently the corps’ commander, to provide security and fight Sunni Arab insurgents.

SCIRI and Dawa want Iraq to be an Islamic state. They propose to make Islam the principal source of law, which most immediately would affect the status of women. For Muslim women, religious law—rather than Iraq’s relatively progressive civil code—would govern personal status, including matters relating to marriage, divorce, property, and child custody. A Dawa draft for the Iraqi constitution would limit religious freedom for non-Muslims, and apparently deny such freedom altogether to peoples not “of the book,” such as the Yezidis (a significant minority in Kurdistan), Zoroastrians, and Bahais.

This program is not just theoretical. Since Saddam’s fall, Shiite religious parties have had de facto control over Iraq’s southern cities. There Iranian-style religious police enforce a conservative Islamic code, including dress codes and bans on alcohol and other non-Islamic behavior. In most cases, the religious authorities govern—and legislate—without authority from Baghdad, and certainly without any reference to the freedoms incorporated in Iraq’s American-written interim constitution—the Transitional Administrative Law (TAL).

Advertisement

Dawa and SCIRI are not just promoting an Iranian-style political system—they are also directly promoting Iran- ian interests. Abdel Aziz al-Hakim, the SCIRI leader, has advocated paying Iran billions in reparations for damage done in the Iran–Iraq war, even as the Bush administration has been working to win forgiveness for Iraq’s Saddam-era debt. Iraq’s Shiite oil minister is promoting construction of an export pipeline for petroleum from Basra to the Iranian port city of Abadan, creating an economic and strategic link between the two historic adversaries that would have been unthinkable until now. Iraq’s Shiite government has acknowledged Iraq’s responsibility for starting the Iran–Iraq war, and apologized. It is an acknowledgment probably justified by the historical record, but one that has infuriated Iraq’s Sunni Arabs.

Through its spies, infiltrators, and sympathizers, Iran has a presence in Iraq’s security forces and military. It is virtually certain that Iran has access to any intelligence that the Iraqis have. Not only does Iran have an opportunity to insert its people into the Iraqi apparatus, it also has many Iraqi allies willing to do its bidding. When I asked an Iraqi with major intelligence responsibilities about foreign infiltration into Iraq, he dismissed the influx from Syria (the focus of the Bush administration’s attention) and said the real problem was from Iran. When I asked how the infiltration took place, he said simply, “But Iran is already in Baghdad.”

On July 7, the Iranian and Iraqi defense ministers signed an agreement on military cooperation that would have Iranians train the Iraqi military. The Iraqi defense minister made a point of saying American views would not count: “Nobody can dictate to Iraq its relations with other countries.” However, even if the training is deferred or derailed, it is only the visible—and very much smaller—component of a stealth Iranian encroachment into Iraq’s national institutions and security services.

So far, the Bush administration seems surprisingly untroubled by the influence in Baghdad of a country to which it has shown unrelenting hostility. But should the President want to understand why the Shiites have shown so little receptivity to his version of democracy, he need only go back to his father’s presidency. On February 15, 1991, the first President Bush called on the Iraqi people and military to overthrow Saddam Hussein. The Shiites made the mistake of believing he meant it. Three days after the first Gulf War ended, on March 2, 1991, a Shiite rebellion began in Basra and quickly spread to the southern reaches of Baghdad. Then Saddam counterattacked with great ferocity. Three hundred thousand Shiites ultimately died. Not only did the elder President Bush not help, his administration refused even to hear the pleas of the more and more desperate Shiites. While the elder Bush’s behavior may have many explanations, no Shiite I know of sees it as anything other than a calculated plan to have them slaughtered. By contrast, Iran, which backed SCIRI and Dawa and equipped the Badr Brigade, has long been seen as a reliable friend.

4.

Days after the Kurdistan National Assembly convened in June, it elected Kurdistan Democratic Party leader Masood Barzani as the first president of Kurdistan. Before so doing, it passed a law making him commander in chief of the Kurdistan military but then specifically prohibiting him from deploying Kurdistan forces elsewhere in Iraq, unless expressly approved by the assembly. (Kurdistan retains some 50,000 peshmerga under the direct control of the Kurdistan government.) The assembly also banned the entry of non-Kurdish Iraqi military forces into Kurdistan without its approval. Kurdish leaders are mindful that their people are even more militant in their demands. Two million Kurds voted in a January referendum on independence held simultaneously with the national ballot, with 98 percent choosing the independence option.

Kurdistan’s leaders would like Iraq to be a loose confederation in which Kurdistan makes its own laws, retains its own military, the Iraqi military stays out, and Kurdistan manages its own oil and water resources. Although Iraq’s interim constitution, the TAL, talks of “federalism,” it has been implemented so as to create no more than a confederal relationship between Kurdistan and the rest of Iraq. The Kurdish leaders would accept its continuation provided the text was clarified to assure Kurdistan’s ownership of petroleum in the region and if the status of the disputed region of Kirkuk were resolved.

While the Shiite religious parties accepted the TAL when it was promulgated in 2004, the Kurds now believe they don’t mean it. When he swore in his cabinet on May 3, 2005, Shiite Prime Minister Jaafari eliminated the reference to a “federal Iraq” from the statutory oath of office; this so angered Barzani that he forced a second swearing-in ceremony. Some Shiite drafts for Iraq’s permanent constitution would sharply restrict Kurdistan’s autonomy and demote Kurdish from its current status at the federal level as an official language equal with Arabic. The Kurdish leaders also worry that the Shiites will try to eliminate Kurdistan’s current ability to modify the application of national law in Kurdistan; they fear that the Shiites will, at least, stop secular Kurdistan from rejecting the imposition of Islamic law.

5.

In his speech, President Bush alluded to the importance of Iraqis meeting their deadlines. The deadline that looms is August 15 for the National Assembly to adopt a constitution. As of this writing, great effort has been devoted to questions of expanding the drafting committee to include Sunni Arabs. Very little has been done on the substantive work of writing a constitution.

Because the differences among Iraq’s three communities are so great, it seems unlikely that they can find common ground on a constitution by August 15, if ever. But the deadline could be met if the assembly agrees simply to continue the TAL, with some modifications of the provisions on oil and Kirkuk. The Shiites have a desire similar to the Kurds’ for oil to be owned and managed by the regions. The Shiite south sits on top of nearly 80 percent of Iraq’s known oil and, like the Kurds, the Shiites feel the old system of central management enriched Baghdad and the Sunni Arabs without providing any benefits to the regions owning the oil. Shiite leaders from the three oil-rich southern governorates have already proposed to create a southern region that, like Kurdistan, would have its own oil.

Control over Kirkuk, an ethnically mixed governorate, will be much more difficult to solve. The Kurds insist it is the heart of Kurdistan, and believe a great injustice was done when Saddam expelled Kurds from the area and resettled Arabs in their place. But Kirkuk also has indigenous Arabs, Turcomans, Assyrians, and Chaldeans. The Kurds and Shiites could make a deal to have a referendum to determine Kirkuk’s future, which, since the Kurds are now again likely to have a majority, could be significantly at the expense of the Sunni Arabs. But not entirely, since Kirkuk’s Arabs and Turcomans are both Sunni and Shiite.

In the coming constitutional battle, Kurdistan leaders—and many secular Arab Iraqis—will be drawing the line on three principles: secularism, the rights of women, and federalism. They fear that President Bush will be more interested in meeting the August 15 deadline for a constitution than in its content, and that they will be under pressure to make concessions to the Shiite majority. It may be the ultimate irony that the United States, which, among other reasons, invaded Iraq to help bring liberal democracy to the Middle East, will play a decisive role in establishing its second Shiite Islamic state.

In fact an agreement on the constitution in the National Assembly may not end Iraq’s sectarian divisions but set the stage for new battles. Voters must approve the constitution in a referendum scheduled for October 15, and under the TAL two thirds of the voters in any three governorates may veto it. There are three Kurdish governorates, but also three Sunni Arab governorates. Even if Kurdistan’s leaders reluctantly accept a Shiite-written constitution, the independence-minded Kurdistan electorate may reject it. Moreover, the Sunni Arabs could easily use the referendum to torpedo any Shiite–Kurdish agreement.

The ratification clause of the TAL creates a timed fuse that could blow Iraq apart, and as is true for so much else that has gone wrong, it is American arrogance and ignorance that are to blame. When Iraq’s Governing Council was considering the TAL in February 2004, the Kurds came up with a simple proposal to protect their existing autonomy: the permanent constitution would come into effect if ratified by a majority of Iraqis, but would only be operative in Kurdistan if ratified by a majority of Kurdistan’s voters. This simple formula, which involved no veto on the ratification on the constitution but only a geographic limitation on where it would apply, was largely acceptable to the Arab Iraqis. But it was not acceptable to the American administrator, L. Paul Bremer, who did not want to concede that Iraq’s ethnic communities should be treated differently. He came up with the three-governorate formula, preparing the way for a future train wreck.

6.

There are two central problems in today’s Iraq: the first is the insurgency and the second is an Iranian takeover. The insurgency, for all its violence, is a finite problem. The insurgents may not be defeated but they cannot win. This, of course, raises a question about what a prolonged US military presence in Iraq can accomplish, since there is no military solution to the problem of Sunni Arab rejection of Shiite rule, which is now integral to the insurgency.

Iraq’s Shiites endured decades of brutal repression, to which the United States was mostly indifferent. Iran, by contrast, was a good friend and committed supporter of the Shiites. By bringing freedom to Iraq, the Bush administration has allowed Iraq’s Shiites to vote for pro-Iranian religious parties that seek to create—and are creating—an Islamic state. This is not ideal but it is the result of a democratic process.

The Bush administration should, however, draw the line at allowing a Shiite theocracy to establish control over all of Iraq. This requires a drastic change of strategy. Building powerful national institutions in Iraq serves the interest of one group—today it is the Shiites—at the expense of the others, and inevitably produces conflict and instability. Instead, the administration should concentrate on political arrangements that match the reality in Iraq. This means a loose confederation in which each of Iraq’s communities governs itself, and is capable of defending itself. It may not be possible to accomplish this in a constitution, since the very process of writing a constitution forces these communities to confront issues—religion, women’s rights, ownership of oil, regional militaries—that are hard to resolve ideologically.

Many of these issues, however, could conceivably be worked out practically. For example, the Iraqi Ministry of Oil and the Kurdistan government are currently cooperating on fulfilling oil contracts made by the Kurdistan government, without having to face the constitutional issue of who owns the resources. Without having to make a constitutional decision on religion, the Shiite south can apply Islamic law as it now does and Kurdistan can remain secular.

War always has unintended consequences. Currently we are pursuing a strategy that will not end the insurgency but that plays directly into the hands of Iran. No wonder Agha Panayi, the Iranian intelligence official, was smiling.

—July 14, 2005

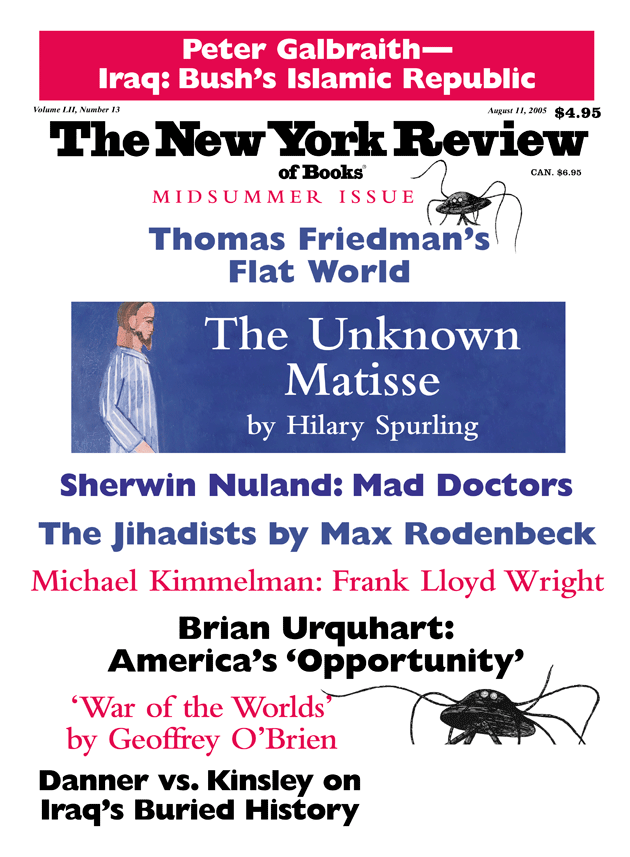

This Issue

August 11, 2005