The need, even the necessity, for United States leadership in international affairs has, at least since 1945, been taken for granted by most of the world’s governments. Great international projects, including the United Nations itself, were carried out as the result of American initiatives. In the immediate postwar years when recovery and rehabilitation were an overwhelming priority, even the Soviet Union tacitly acknowledged US leadership and accepted it in practice in the work of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, which was sponsored by the US. During the cold war, countries outside the Soviet bloc accepted the United States at its own valuation as “leader of the free world.” Again, in the euphoria of the immediate post–cold war period, especially in parts of the world stricken by man-made or natural disasters, the United States was seen as, in Madeleine Albright’s words, “the indispensable nation.”

Only in the twenty-first century has this unique and previously unassailable position been subjected to question and doubt. This is happening at a time when the traditional threat to peace, wars between great powers, has, for the moment at least, receded. It has been supplanted by a series of global threats to human society—nuclear proliferation, global warming, terrorism, poverty, global epidemics, and more. These challenges can only be addressed by collective action, led by determined and imaginative men and women. In the first years of the new century it would seem that leadership of that kind would still most effectively come from the United States. This would be acceptable to the rest of the world, however, only if there is an agreed set of consistent and sound policies evolved through consultation and consensus. Current United States policy does not meet that requirement. In view of the seriousness of the new threats, however, there is not a moment to lose.

1.

Richard Haass addresses this situation in his new book, The Opportunity: America’s Moment to Alter History’s Course. Haass’s credentials are impressive. He has served in the State Department and the Pentagon under Presidents Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush. He has had ample practical experience of the difficulty of launching carefully thought out policies amid the ideological currents and political storms that dominate Washington—a political climate that has seldom been as eccentric or ideologically charged as it is today. In The Reluctant Sheriff: The United States After the Cold War (1998),1 written during the Clinton administration, Haass addressed the problem of how “to bridge the gap between the demands of regulating a deregulated world and a society reluctant to play the role of sheriff,” i.e., the United States. Under the Bush administration he served as director of policy planning for the State Department and was a principal adviser to former Secretary of State Colin Powell. He is currently president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

A series of important but low-key disagreements with current US policy run throughout Haass’s book and set the stage for his ideas, which he presents as an outline for a new foreign policy, but with hardly any comment on how it might be achieved politically in the US. As a general rule Haass believes that skillful diplomacy, in its broadest sense, is Washington’s best weapon in the twenty-first century, and that military force must be used only as a last resort. “During the 1990s,” he writes, “the Clinton administration did too little to shape the world; more recently, the administration of George W. Bush has often tried to do too many things in the wrong way. The result, though, is the same: We risk squandering the historic opportunity at hand.”

Haass emphasizes the by now all too apparent limitations of US military strength—two million strong at the end of the cold war and now nearly one and a half million. The US defense budget of $500 billion a year exceeds the combined defense budgets of China, Russia, India, Japan, and Europe. Confirming the warning of the former army chief of staff General Eric Shinseki, Haass points out that current operations to achieve stability in Iraq require a great deal of manpower and that no other major efforts can be undertaken by the United States as long as the Iraq military involvement lasts. Haass stresses the point, also made recently by retired Marine General Anthony Zinni, that opponents of American power have by now learned the lesson of the 1991 Gulf War: that the conventional battlefield is the one place not to fight the United States. The preferred weapons of the weak have therefore become terrorism and armed insurgency. They could also include weapons of mass destruction, or at least a credible threat to use them if they could be obtained or built.

Haass maintains that expensive “wars of choice,” such as those in Vietnam and Iraq, “that call for open-ended sacrifice for uncertain ends are simply not sustainable.” He also deplores the tendency to revert to the old system of competitive power politics, which distracts attention and resources from the real challenges. He is convinced that it is an illusion to strive for a world dominated by American military superiority. Instead the aim should be to “integrate other states into American-sponsored or American-supported efforts to deal with the challenges of globalization.” In a rather Delphic utterance he claims that the “United States does not need the world’s permission to act, but it does need the world’s support to succeed.”

Advertisement

Haass dismisses the Bush administration’s announced goal of promoting democracy as the keystone of foreign policy. There are too many pressing threats—genocide, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, and climate change—that put the lives of millions at risk; and the emergence of democracy is more or less irrelevant to successfully dealing with most of them. Democratization should be just one element in a balanced foreign policy.

Among the unnecessary risks now being run, two are particularly dangerous, in Haass’s view. It is insane, he believes, for the US to gamble on the indefinite willingness of China to hold vast quantities of dollars and Treasury bonds, thus enabling the United States to import far more than it exports and to run huge deficits, while frequently lecturing it on human rights and other matters.2 A refusal of China to continue to buy US bonds or to hold its currency could put the US in a dangerous position. Haass writes that “a policy of guns, butter, and lower taxes is not sustainable.” He also argues that the second problem, the current worldwide spirit of anti-Americanism and the perception that Americans do not have a decent respect for the opinions of mankind, fostered in the last four years by many gratuitous policy moves, must be reversed. As he discreetly puts it, it is “essential that policies and how they are promoted be adjusted.”

As for other immediate problems, Haass notes that

speaking of a “war on terrorism”…does not help to define either the threat or the solution…. For terrorists there is no battlefield—or every place is a battlefield, from airports and shopping malls to restaurants and movie theaters.

While wars come to an end, there is unlikely to be a definite end to terrorism. Terrorism would be better understood, and treated, as a disease, with specific “steps that can be taken to eradicate or neutralize specific viruses or bacteria.”

In the chapter “Nukes on the Loose” Haass writes that the objective of the United States should be to de-legitimize and reduce, as far as possible, “the currency and symbolic value” of nuclear weapons. In particular the US should reconsider its intention to develop new nuclear weapons, such as the “bunker-buster,” whose functions can be performed by conventional weapons. In order to strengthen the effort to deter more countries from developing nuclear weapons, the US should also reconsider its opposition to the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Haass criticizes the policy of preemption or prevention, proclaimed by President Bush at West Point in June 2002. More than any other form of intervention, preventive attacks threaten to undermine international conventions and particularly, one might add, the UN Charter, which prohibits interventions involving military force except in self-defense. “A world,” Haass writes,

in which preventive attacks were common would be a dangerous and disorderly world, in some ways an undesirable throwback to times in which states regularly involved themselves in the internal affairs of their neighbors.

As for the practical application of Bush’s policy in Iraq,

Although the Bush administration described its strategy as “preemption,” the substance of its position toward Iraq constituted a clear case of “prevention,” given the uncertain knowledge of Iraqi capacities and the complete lack of evidence of any imminence of hostile attack by Iraq.

For a former Bush administration official, Haass is uncompromising in his criticism of the Iraq invasion. Because it was based on false premises, was widely seen as illegitimate, and lacked full international support, it increased anti-American feeling throughout the world, while diminishing the likelihood of international cooperation in future initiatives. Moreover, the Iraq adventure has become a “magnet and a school for terrorists.” It is an unwarranted war that ignores the essential balance between the proclaimed benefits and the real costs. If Haass held such views at the time of the invasion, it must have been a strange and distressing experience for him to remain a very senior official in the State Department during the first term of the Bush administration.

Referring to the ongoing controversy over the UN Oil-for-Food Program, in which much righteous indignation has been directed at the United Nations from Washington, Haass points out that between the wars Saddam Hussein’s main source of hard currency was the payments he received from smuggling oil to Jordan, Syria, and Turkey, an activity that was tolerated by the US. These shipments, he writes, amounted to 84 percent of Saddam’s hard currency. The United States, he thinks, should have shut down this smuggling route and subsidized the economies of Jordan and Turkey instead. He estimates that kickbacks from the much-abused UN Oil-for-Food Program, a program, incidentally, that fed and supported a large majority of the Iraqi people for over six years, may have accounted for some 16 percent of Saddam’s hard currency.

Advertisement

“Regime change” is not a new idea. The British, French, and Israelis tried it with disastrous results at Suez in 1956. Haass feels that the US might have learned from what happened in Iran twenty-five years ago “that unattractive authoritarian regimes can be replaced by something far worse.” He quotes George Kennan’s famous guide to dealing with the Soviet Union,3 in which Kennan proposed long-term, patient, but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies, and increasing

enormously the strains under which Soviet policy must operate…to promote tendencies which must eventually find their outlet in either the break-up or the gradual mellowing of Soviet power.

Haass also advises against a policy of refusing to have any dealings with an authoritarian regime (as during the last forty-five years with Cuba) while calling at the same time for a change in its regime. The United States engaged in active diplomacy with the Soviet Union throughout the cold war, and regime change eventually took place.

Haass believes that there is now a clear opportunity for a better world, but that it may well soon disappear:

This could turn out to be an era of prolonged peace and prosperity, made possible by American primacy successfully translated into influence and effective international arrangements. Or it could turn out to be an era of gradual decay, an incipient modern Dark Ages, brought on by the loss of control on the part of the United States and the other major powers and characterized by a proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, failed states, and growing terrorism and instability.

He feels that the United States should use its power and influence to persuade the major powers, along with as many other countries, organizations, corporations, and people as possible,to sign up to and support a set of rules, policies, and institutions that would bring about a world in which armed conflict between and within states is the exception; where terrorists find it difficult to succeed; where the spread of weapons of mass destruction is halted and ultimately reversed; in which markets are open to goods and services and in which societies are free and open to ideas; and where the world’s people have a good chance to live out lives of normal span free from violence, extreme poverty, and deadly disease.

With a few contemporary additions, these goals are ones that many of us hoped the governments in the UN would pursue sixty years ago. As an ex-military, newly recruited member of the UN Secretariat, I well remember the righteous wrath that the least breath of skepticism about achieving such results aroused among the members of the remarkable early United States delegations to the UN, which included such people as Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson. As it turned out, governments were willing to accept the UN’s rules on paper but didn’t always find it easy or profitable to obey them. Worst of all, relations among the designated guardians of the peace, the permanent members of the UN Security Council, soon deteriorated to such an extent as to pose the most terrifying possible threats to world peace. Even so, when the world organization was not completely paralyzed by great power rivalries or talked to a standstill by bickering governments, the United Nations system, usually with United States leadership and support, made a good start on much of Haass’s agenda. As he proposes, now is the time and the opportunity to make significant progress on the basis of what has already been done.

To achieve such progress Haass recommends a US policy of “integration,” which he defines as

the ambition to give other powers a substantial stake in the maintenance of order—in effect to co-opt them and make them pillars of international society—so that they will come to see it in their self-interest to continue working with the United States and damaging to their interests to have a falling-out with the United States.

This may seem a patronizing, and mildly threatening, approach to the other 191 or so sovereign nations of the world, including several very large and potentially powerful ones. It is just as well, as Haass mentions elsewhere, that “a good deal of this book has been written for Americans and directed at the current and future governments of the United States.” In the brief, victorious, visionary days of 1945 and 1946, it would have been quite unnecessary to state that American ambition and leadership were central to what happened in the world. Haass notes the achievements of the immediate post–World War II period with admiration, and wonders whether the United States can prove to be equally creative now.

2.

Of the relatively new generation of global issues, Haass singles out four problems as especially susceptible to the process of integration—genocide, terrorism, the proliferation of WMDs, and the need for open trade. An essential requirement of success with these and other matters, he argues, is a re-evaluation of the concept of national sovereignty. All the current talk of UN reform will, I would add, have little reality if the hitherto frustrating conflict between national sovereignty and international responsibility is not, at least to some extent, resolved. Haass rightly points out that any effective system of universal security and protection will require the dilution of national sovereignty, especially when humanitarian intervention is needed to prevent mass killing and other disasters. Haass’s discussion of this important and fundamental problem should be heeded, especially by those who clamor for United Nations reform.

Haass’s chapter on terrorism includes a frank discussion of the Israeli– Palestinian problem. He points out that true Palestinian democracy, much discussed in recent months, is desirable but not essential to the peace process. What matters is the Palestinian government’s willingness and ability to sign, and to carry out, a peace agreement. As he rightly emphasizes, the United States must make such an agreement, and the establishment of a Palestinian state, a diplomatic priority. The aim should be a settlement based on the 1967 armistice, offering the Palestinians territorial compensation for the land outside those lines that Israel ends up keeping.

When it comes to the danger of nuclear weapons, Haass writes, “Mutually assured destruction is a simple concept ill-suited to a complex multipolar region or world.” That nuclear proliferation is not only a global threat but also a matter of widespread disagreement was underlined by the recent UN conference on the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). After weeks of debate, the nearly ninety countries that attended the meeting failed even to reach agreement on its agenda. There are now five established nuclear powers, which also happen to be the five permanent members of the UN Security Council—all have signed the NPT; and three nuclear powers, Israel,4 India, and Pakistan, that still refuse to sign it. One country, North Korea, is credited with possessing nuclear weapons, and another with nuclear know-how, Iran, is seen by many governments as aspiring to do so.

Meanwhile the already complicated problems of international control of nuclear weapons have now become more formidable than ever. The possibility has to be faced that the weapons may fall into the hands of terrorists. A private trade in nuclear materials organized by the Pakistan physicist A.Q. Kahn has recently been exposed. The members of the old nuclear club have immense stockpiles of these weapons; and in Russia, and some other countries, they are poorly secured. Finally, there is the widely perceived hypocrisy of those, such as the US and Russia, that insist, as a matter of national security, on keeping huge nuclear stockpiles while excoriating other countries for any attempt to acquire nuclear weapons themselves.

Haass, in considering the difficulties of dealing with North Korea and Iran, writes in the abstract language of foreign policy symposia: “US policymakers would be wise to contemplate a strategic future in which preventive action played little or no role”—words that can be translated into a warning not to bomb Iranian and North Korean nuclear installations. He adds that “when non-proliferation efforts fail, the major powers must have a concerted, well thought out response ready.” Haass does not make it clear what that response should be. But he is right that there are no clear-cut solutions available, certainly not the ballistic missile defense system once called Star Wars. “Not only is it uncertain whether it will work,” he writes,

despite the considerable investment, but the most likely threats from nuclear weapons are more likely to arrive in the United States in some container rather than on top of a missile.

Haass is more specific when he discusses energy dependency—“the Achilles Heel of the United States”—which is caused by “the enormous gap between what the United States produces and what it consumes.” Producing 10 percent of the world’s oil and consuming 25 percent of it makes US goods more expensive, contributes to inflation, the fiscal deficit, and the trade deficit, and makes a hugely disproportionate contribution to global warming. America’s excessive use of energy also distorts US foreign policy, endangers national security, and jeopardizes both the US and the world economies.

Haass is not impressed with the Bush administration’s approach to the energy problem:

The gains that would come from opening up the Arctic Wildlife Refuge in Alaska would be modest and would not change the facts about where the United States gets its energy.

For the United States he believes that the main answer must lie mainly in reducing energy demand and in lower, and more efficient, energy use, “the only way to reduce the financial, strategic, and environmental costs of current policy.” About how such a sensible, and sensitive, goal is to be achieved he is silent.

Haass emphasizes the importance of reaching agreement on the rules for international intervention. That the UN Security Council is now the sole source of legitimacy for military and other intervention he finds unsatisfactory. As many others have done, he argues that the Council’s composition is anachronistic and unrepresentative, and the permanent members often don’t agree on what is a “legitimate purpose in the world” and on what specific international actions are legitimate in the world today. This lack of agreement is reflected in the Council’s failure to take decisive action in such urgent disasters as Bosnia or Kosovo, and in many cases in earlier years. Haass concludes that “it is this absence of complete consensus and the Security Council’s rules and composition that make it and the UN too brittle and too narrow an instrument to be the centerpiece of any attempt at this moment to build a more integrated world.” In his view the Council should not be the sole source of legitimacy.

Haass therefore reflects on the possible use of other, less universal, international groups—NATO, the EU, and various regional groups—to intervene by military and other means if the Security Council cannot agree. Personally I think it would be a great mistake to water down the principles of the UN Charter, which were agreed on at a high point of international cooperation and solidarity following World War II. The periodic inability of the Security Council to agree on vital matters is, and always has been, a major shortcoming of the UN, and various ad hoc strategies have been used to take action nevertheless; but to transfer formally the Security Council’s powers to other, less comprehensive groups could easily lead to another major division of the nations of the world and to the violent antagonisms that many nations, for the moment at least, seem to regard as a thing of the past. But Haass is right to raise the problem of the Security Council’s failures and to insist that governments discuss it seriously, even if he cannot present a completely satisfactory solution.

All major powers, Haass writes in his concluding chapter, have a stake in seeing the emergence of an integrated world. The well-known list of dangers—proliferation of WMD, terrorism, neoprotectionism, failed states, global epidemics, drugs, climate change, and doubtless other challenges as well—all have to be met collectively if they are not to overwhelm human society. Obviously a major change both in the spirit and the letter of US foreign policy will be needed before the United States can hope to regain the international respect it once had.

3.

Richard Haass has presented an agenda for United States foreign policy that is realistic, constructive, and conservative in the old sense of the word. His argument can be read as a firm, if restrained, indictment of the foreign policy of the Bush administration. But several questions arise about his basic concept of world “integration” under United States leadership. First, will the rapidly changing world be willing to embrace US leadership as readily as it has done in the past? That will depend on whether US policy can change and also to what extent US leaders can work through the United Nations and its agencies as well as through regional groups and NGOs. Such collaboration will be indispensable if US leadership is to be acceptable to governments that are, in theory at least, coequal sovereign members of those bodies.

Second, Haass criticizes current policies, but he does not suggest how the existing political and ideological climate in Washington could be changed, so that his own proposals and others might be accepted. Nor does he mention the new and growing forces in American political life, some of which have underpinned the policies of the George W. Bush administration both in domestic and in foreign affairs, although he often mentions the widespread anti-Americanism that some of them have aroused. Among these forces are the firm hold of the big corporations, especially on environmental and energy policy; the neoconservative ideology that rejects international organization and international treaties and conventions and favors unilateral military ventures; the growing influence of evangelical religion on the White House, on domestic policy, and on some aspects of foreign policy, including the administration’s approach to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict; and the relentlessly hostile partisanship of congressional politics, which can have a paralyzing effect in Washington.

How can such powerful influences be countered and controlled so that the “Great Opportunity” that is the subject of Haass’s book can be grasped by a confident United States government whose leadership will be welcomed by other nations? One gets little sense from Haass’s book of the problems posed by the social and political forces in the country whose policies he wants to change.

Third, will the United States be able to supply the quality of leadership needed to face the formidable challenges of the twenty-first century? Some of the issues that Haass addresses are of decisive importance to the future of the human race. They will require solutions far more drastic and imaginative than anything that can be agreed on at present, either within the United States or in the world at large.

Haass refers with some awe to the achievements of the US during the period following World War II. In 1945 the world had just endured more than six years of global war and its peoples were gasping for relief and hoping for improvement. United States policy at that time was being created on a grand and visionary scale and executed by a remarkable generation of leaders and public servants. They were pragmatic idealists more concerned about the future of humanity than the outcome of the next election; and they understood that finding solutions to postwar problems was much more important than being popular with one or another part of the American electorate. Led by FDR and later by Harry Truman, they provided the peaceful but revolutionary spectacle of the most powerful and richest nation in history dedicating itself to rehabilitating a world wrecked by war and to developing the ideas and building the institutions that might make possible a more just, peaceful, and secure world in the future.

It is worth recalling what this extraordinary burst of political creativity included:

—the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration led by Herbert Lehman, which was instrumental in bringing war-devastated countries, including the Soviet Union and China, back to life;

—the reconstruction and democratizing of Germany and Japan;

—the creation of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund at Bretton Woods;

—the building of the United Nations, inspired by FDR himself and carried out, with the strong support of Harry Truman, by, among others, Adlai Stevenson, Edward R. Stettinius, Senators Arthur Vandenberg, Republican of Michigan, and Tom Connally, Democrat of Texas, and a distinguished team of experts;

—the struggle for a Universal Declaration of Human Rights triumphantly achieved in 1948 by Eleanor Roosevelt and her associates;

—the attempt, which failed, to bring nuclear production under international control before it proliferated (the Acheson-Lilienthal Plan);

—the Marshall Plan, which turned the countries of Western Europe away from chaos and revolution, helped to make them prosperous and well-governed nations, and laid the foundations of the European Union;

—the US-led Korean War, under the UN flag, which convinced the Soviet Union and China that the United States could, and would, lead the world in resisting Communist expansionism beyond its recognized sphere of influence.

This incomplete record at least suggests what serious international leadership entails. These historic initiatives were not realized by repeating clichés and simplistic formulas. They were the creation of some of the nation’s best public servants and intellectuals, and they were made possible by presidential leadership, congressional bipartisanship in foreign affairs, and by an American public that was, for the most part, prepared to accept, with no guarantee of success, expensive long-term projects, like the Marshall Plan, because the administration and Congress had persuaded them that they were essential to the future of the US and the world.

Large fortunes were made in the US during World War II, but there were determined attempts to defend military procurement and other expenditures from the assaults and influence of special interests. A principal weapon in this struggle was the Senate committee, headed by Harry Truman during much of the war, to investigate corruption and mismanagement in the awarding of government contracts. It would have been extremely difficult for a major policy initiative to be sidelined by lobbyists for corporations or other special interests. Toward the end of his presidency, Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, warned against the growing power of the “military-industrial complex.” In our time such interests are vastly more powerful in Washington and can, and do, successfully block the approach to important global problems.

One symptom of the vast current influence of corporate business is the tendency to cover up or soften informed predictions about universal problems like energy, the environment and global warming.5 The results are dismaying. It seems likely, for instance, because of Western energy consumption and increasing demand from India and China, that, sooner than previously thought, affordable oil will become steadily scarcer, with an economic and social impact that will be staggering and universal. Attempts to increase energy efficiency, which Haass advocates, are all very well, but surely real leadership demands something more radical, an intensive search for alternative sources of energy through an international undertaking on the scientific, intellectual, and financial scale of the World War II Manhattan Project that produced a nuclear bomb in just over two years. How soon will there be an administration in Washington that could even consider such a step?

Global warming is an even more complex and frightening issue than the future of energy, and perceptive leadership would treat it as the threat to human (and animal) society that it already appears to be, instead of balking under corporate pressure at serious steps to do something about it. (At the recent G-8 conference President Bush was willing to acknowledge only that climate change is a “long-term” challenge.)

Richard Haass is right that a fleeting opportunity must be grasped before it is too late. But, in view of the forces that stand in the way of accepting such a historic challenge, it is also essential to consider how the United States is to muster the public consensus and the political will and sense of responsibility to face up to it.

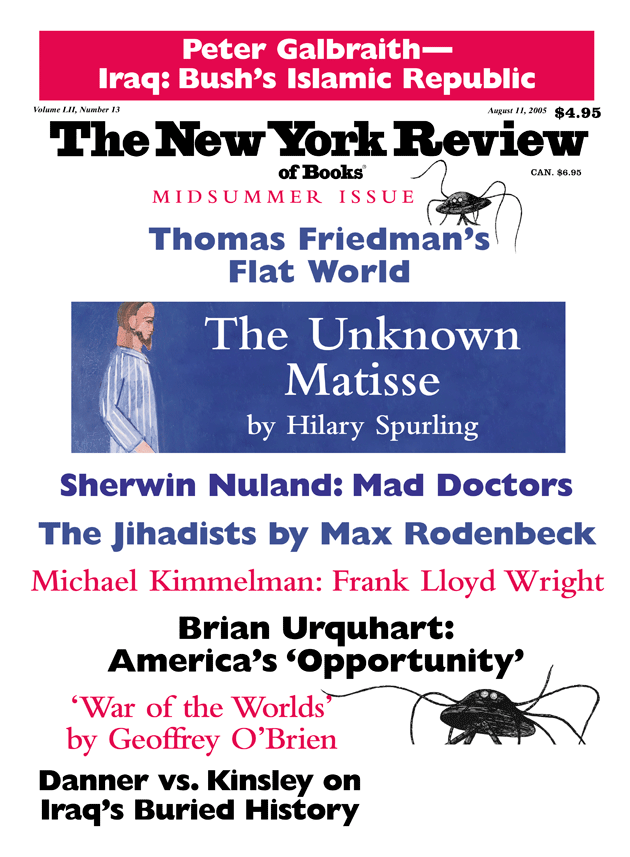

This Issue

August 11, 2005

- 1

-

2

See, for example, “Rumsfeld Issues a Sharp Rebuke to China on Arms,” The New York Times, June 4, 2005. ↩

-

3

His “long telegram” that found its way into Foreign Affairs magazine in 1947. ↩

-

4

On Israel’s nuclear weapons, Haass out-Orwells the Orwell of Animal Farm: “Although it is right to oppose the emergence of new nuclear weapons states in all circumstances, it is also right to oppose it more in some than in others.” ↩

-

5

A White House aide, Philip Cooney, a former energy lobbyist, recently had to resign when it was revealed that he had taken it upon himself to soften a report on global warming. ↩