In response to:

The Lost Children of AIDS from the November 3, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

The New York Review has published an extract from Helen Epstein’s book titled “The Lost Children of AIDS” [November 3]. Though Helen Epstein’s intentions could be honorable, many of her conclusions are factually incorrect; she made many assumptions and generalizations without any careful consultation and missed the opportunity to use her efforts to the greater benefit for the children affected by AIDS. The review refers to at least two nongovernmental organizations operating in South Africa, Hope Worldwide South Africa (HWW) and NOAH. Both entities are community-based organizations with specific focus on helping those affected by HIV/ AIDS through funds provided by the US government under the PEPFAR initiative.

HWW has sixteen years of community-based HIV/AIDS program experience within informal settlements around Africa. Our goal is to treat each child as if they were our very own. Our management and staff have worked hand-in-hand with hundreds of community-based organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and local authorities in Africa to provide quality services to children and families affected by AIDS. HWW has trained 936 staff members from 188 organizations like Sizanani in South Africa on community-based care, support, and prevention between October 2004 and September 2005 and provided subgrants to community organizations as permitted by our donors. The South African program has grown because of its impact on the children and families affected by AIDS. For example, each year HWW provides 120 tons of food to the fifty community AIDS programs it serves.

The review links Oprah’s goodwill to HWW’s attempts to solicit funding. Nothing could be further from the truth. A period of almost two years elapsed between Oprah’s visit to South Africa and HWW’s securing of funds for the ANCHOR program. In the same vein, continuous reference is made to Sizanani and Elizabeth Rapuleng and how HWW has neglected this orphan program. Again, this is far from the truth. Not only was Elizabeth employed by HWW during the time of Oprah’s visit and thereafter, but HWW arranged R200,000 ($30,000) in the following twelve months for Sizanani after Elizabeth had resigned. HWW also trained ten Sizanani staff in psychosocial support (PSS) for children and in voluntary counseling and testing. Helen fails to highlight the financial and material support (food and clothing) provided by HWW, but unwittingly refers to requirements pertaining to statistics, paperwork, and a memorandum of understanding. Reporting is a fundamental component of being a fund recipient and it assists beneficiary organizations to accept the responsibility of monitoring and evaluation, which improves program management and sustainability.

Helen continues with her inaccuracies as emotive comparisons are made between office locations but she fails to note that several of the HWW programs are run from shipping containers as well. She also fails to mention that HWW rents its premises at subsidized commercial rates in areas that are definitely not the most exclusive neighborhoods in South Africa. Anyone who has visited the office would readily acknowledge this mistake.

It seems very unlikely that HWW would not have returned any of Helen’s calls after HWW had gone to great lengths to receive Helen and Jonathan Cohen for an impromptu interview in Johannesburg. The next day followed with a site visit to the Thusanang Primary School in White City, Soweto, where a psychosocial support program for children was demonstrated and discussed with a school staff member. Helen failed to mention the tremendous impact of the PSS program on children devastated by AIDS that she saw with her own eyes. Dr. Mimie Sesoko, an expert on PSS for children and a member of the board of directors of HWW, assisted the interview and conducted the site visit but she was never asked any questions pertaining to funding or the use of funds. In fact, Helen has never left any telephone messages, fax messages, or e-mail correspondence for any HWW staff despite meeting them in Soweto.

In conclusion the Community AIDS Programs of HWW have:

- No “empty targets”—only desperate children,

- No “impossible work”—only dedicated staff,

- No “mysterious memorandum”—only supportive agreements,

- No “overly ambitious targets”—only desires to help more children,

- No “exclusive neighborhood offices”—only borrowed and rented space,

- No “(imagined) concerns”—only the reality of death and serious needs,

- No “a number of staff (who have quit)”—only motivated and loyal staff who have grown in stature or have been recruited by partner organizations,

- No “strategy to leverage the names of children for gain”—only doing the most we can with the best we have to help as many children as possible with their futures, their hopes, and their dreams.

Please communicate this response to Helen Epstein from the management, staff, and clients of HWW.

We want to thank the Office of the Global Coordinator on AIDS, USAID, the South African government, the Rotarians for Fighting Aids, NOAH, and countless community partners we work with in the fight against AIDS for their heartfelt devotion, tireless efforts, and tremendous commitment to helping families devastated by AIDS in South Africa.

Dr. Mark Ottenweller

Director, Hope Worldwide

Randburg, South Africa

Helen Epstein replies:

Dr. Ottenweller’s letter raises many of the issues I and others find so troubling about the lack of transparency in many current approaches to public health in developing countries. In trying to show that ” The Lost Children of AIDS” contains “factual errors,” this letter makes misleading statements of its own.

For example, my point was not to “link Oprah’s goodwill to HWW’s attempts to solicit funding.” I wrote: “We can imagine that [Hope’s] chances [of receiving PEPFAR funding] were not hurt by the publicity from the party and the link with Oprah.” In any case, the point of discussing the Oprah party was that the Sizanani community organization was supporting those children, not Hope; and yet this is not mentioned in the film or in Hope’s press release about the party.

Advertisement

“Lost Children” clearly states that Elizabeth Rapuleng worked for Hope when she started Sizanani. However, Hope was not supporting Sizanani at the time. It is misleading to claim that Hope “arranged R200,000 ($30,000) in the following twelve months for Sizanani after Elizabeth resigned.” For one thing, “arranging” money is not the same as “giving” money. For another, that money came from an independent donor who wanted to support Sizanani directly. Although Elizabeth met that donor through a sympathetic former Hope employee, Hope management had nothing to do with obtaining that grant.

Dr. Ottenweller states that Hope “trained ten Sizanani staff in psychosocial support (PSS) for children and in voluntary counseling and testing.” According to an e-mail signed by Elizabeth and her entire staff, this is not the case. No one from Sizanani has been trained by Hope except for Elizabeth, who was trained when she worked there.

Dr. Ottenweller writes that “Lost Children” does not “highlight the financial and material support (food and clothing) provided” by Hope. However, “Lost Children” clearly mentions “occasional donations of food and clothing” from Hope to Sizanani. It does not “highlight” them because of the enormous amount of work Elizabeth is doing without Hope’s help.

While it is true that reporting statistics is “fundamental” for PEPFAR recipients, as “Lost Children” emphasizes, it is preferable if organizations report on beneficiaries they are actually supporting. The conditions described in the memorandum of understanding offered to Sizanani by Hope did not make it clear how Hope was intending to help Sizanani’s children.

It is true that Jonathan and I met with Hope’s Mimie Sesoko and also visited a school where two of Hope’s counselors were introducing the bereavement curriculum and counseling program. “Lost Children” describes these programs as “valuable”—but argues that they cannot possibly meet the profound needs of the many severely neglected children in the area. That is why Sizanani is so important. The teachers and Hope counselors at the school told us as much. Hope—presumably aiming to reach as many children as possible, as quickly as possible—requires its counselors to move on to a new school at the end of each year. While this increases the number of children Hope can claim it has helped, it can be very hard on children who become attached to those counselors. We were told how painful the loss could be. Hope’s counselors do train teachers to continue the counseling program, but even highly committed and sensitive teachers cannot meet the emotional and other demands of so many needy children on their own because they are overwhelmed with other responsibilities.

Because Mimie Sesoko was not involved in the decisions regarding Sizanani, or Hope’s policies regarding community-based groups in general, I attempted to arrange an interview with Dr. Ottenweller after I returned to New York. I contacted Hope’s headquarters in Pennsylvania and was put in touch with Randy Jordan. He asked me to follow up with an e-mail, after which he would arrange for me to interview either Dr. Ottenweller or someone else from Hope’s South Africa office by phone. I sent the e-mail in July (available on request) and left two phone messages. I have yet to receive a reply.

USAID did finally send me a copy of Hope’s original grant proposal, according to which the organization will receive $8,190,607 for ANCHOR. A budget was not attached. However, the document does state that subgrants of between $1,000 and $20,000 will be given to some thirty organizations in the four countries in Phase I of the grant. Thus between $30,000 and $600,000 of roughly $8 million will go to groups working to support children on a sustainable basis. We are not told where the remaining taxpayer dollars will go.

To the Editors:

As the founder and chair of Rotarians for Fighting AIDS, Inc. (RFFA), I would like to bring to your attention the misrepresentation of facts in this article [“The Lost Children of AIDS”] that speak to the author’s obvious prejudices and unsubstantiated criticisms which could potentially impact a great humanitarian effort to help the orphans and vulnerable children in Africa.

I clearly remember receiving a phone call from Ms. Epstein, in particular because she called “out of the blue,” established no context for the call to encourage trust, and was evasive about why she wanted information about the ANCHOR program (the African Network for Children Orphaned and at Risk) and Hope Worldwide (RFFA’s partner in the ANCHOR program). With caution, I kept the conversation brief and referred her to our respective Web sites and USAID directly for program details.

Advertisement

Although Ms. Epstein prides herself on supporting her writing with interviews and extensive research via both public and private documents, she has made factual errors and came to wrong conclusions throughout her article.

Rotarians for Fighting AIDS, Inc. is a Rotarian Action Group approved by Rotary International enabling individual, like-minded Rotarians around the world to work on humanitarian service projects together. As a mother who lost a child to AIDS in 1994, I founded this organization to create a strong link of Rotarians around the world and partner with other organizations working on AIDS in Africa to focus on helping the children affected by HIV/AIDS.

RFFA was asked to partner with several nongovernmental organizations with AIDS expertise because of Rotary’s proven history in battling the polio epidemic, our ethical reputation, and our powerful and significant human resource capacity in Africa (20,000 Rotarians in over 160 clubs). Rotarians are known for their ability to mobilize communities into action. There are several reasons we chose to work with Hope Worldwide: we wanted to work with someone that lives there and actually does the work on the ground in Africa; we required someone with a long-term history of success and a proven best-practice model and who could scale up their capacity quickly in multiple countries; and most importantly, we wanted someone we could trust.

Hope Worldwide/Africa was founded by Dr. Mark Ottenweller, an American physician who took his family to Africa over sixteen years ago to help fight the AIDS pandemic. Ms. Epstein made glittering generalities about “ill-conceived projects designed by foreign technocrats with little sense of African realities,” and then later used Dr. Ottenweller as an example. She obviously did not check out his background and experience. In addition, Dr. Ottenweller has surrounded himself with an excellent management team of young African men and women.

Together Dr. Ottenweller and I established the concept of ANCHOR—a unique blend of a public/private coalition to fight HIV/AIDS, with all partners offering expertise to help care for, support, and educate orphans and vulnerable children. Thus, Coca Cola/Africa became the multinational corporate partner helping ANCHOR with marketing and seed funds; Emory University School of Public Health became the premier monitor and evaluator of the work; and the International AIDS Trust provided assistance in public advocacy. ANCHOR approached USAID for funds and provided them with a multicountry plan. That is how and why we were awarded the $8.1 million USAID grant.

The Hope Worldwide model is holistic in approach because the ultimate answer to the AIDS issue must lie at the community level. Dr. Ottenweller and his staff work at all levels in the community—forming a council with the local schools, the hospitals/ clinics, churches, community leaders (including Rotarians), corporate representatives, and finally the country government. The community council representatives work together to help the children. It is a sustainable model because it trains the local people in how to care for and support the children.

I wonder why Ms. Epstein did not write about the positive things I told her about Hope Worldwide: why she didn’t go to a Hope clinic (quite near the Sizanani clinic) so she could see the poor cinder-block office from which they operate and learn more about the Hope offering on site; or why she based practically all of her conclusions from speaking to a disgruntled ex-employee of Hope Worldwide. It appears Ms. Epstein’s shortcuts in her discovery speak to a hidden agenda and a mind already made up before she wrote the first word.

Although I believe in the critic’s role, it saddens me when an American journalist does not take the responsibility to get her facts straight. An unfortunate consequence of her article will be that many readers, who have never set foot in Africa and do not know the organizations she attacked, will probably believe her. Perhaps Ms. Epstein would better understand the challenges of helping the families in Africa care for and support the AIDS orphans if she walked in the shoes of Dr. Mark Ottenweller for just one month.

Marion Bunch

Founder and Chair of Rotarians for Fighting AIDS, Inc.

Atlanta, Georgia

www.rffa.org

Helen Epstein replies:

Reporters routinely call people who receive large US government grants “out of the blue” and that is why most such organizations generally have press officers or others who are prepared to receive requests for information. As the director of RFFA, it is suspicious that Ms. Bunch considers such calls suspicious. In the event I told her, as I do everyone, that I am a science writer and have been reporting on AIDS in Africa for years and that in this case I was writing a piece on orphans for The New York Review of Books. Had she asked for any other information I would have happily supplied it, but she did not. I was not evasive, she was.

For some reason, both Ms. Bunch and Hope feel obliged to tell readers of The New York Review that the programs that they support are—like Sizanani—located in offices made of rough material, in poor neighborhoods, etc. This is an irrelevant competition. In any case, I would like to have visited Hope’s Meadowlands clinic, but when Jonathan Cohen and I contacted Hope in South Africa, we were not invited there, presumably because we said that we were interested in orphans. That clinic is mainly a health care program for AIDS patients, with occasional support groups for patients and their children—the main purpose of which is not to support orphans but to increase adherence to antiretroviral drugs.

My reporting was not limited to “speaking to a disgruntled ex-employee of Hope Worldwide.” I spoke to several former and current Hope employees, and attempted to obtain more information from Ms. Bunch and from Hope’s offices in Pennsylvania, to no avail (see my reply to Hope, above). Had Ms. Bunch given me any specific, positive information, I might well have reported it, but her description of ANCHOR was limited—like her letter—to vague claims of “creating sustainable models,” “partnering with other organizations,” “mobilizing communities,” “scaling up capacity,” “using holistic approaches,” and “forming community councils,” but she does not tell us how any of this helps children.

Finally, nothing in Ms. Bunch’s letter contradicts a single fact in “Lost Children.”

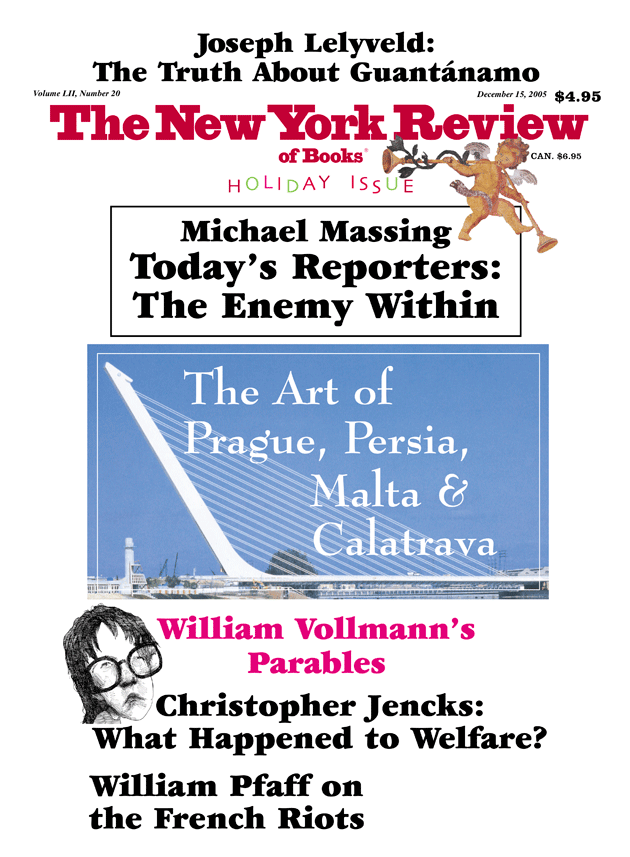

This Issue

December 15, 2005