In response to:

The Right to Life from the May 12, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

I read Hilary Mantel’s penetrating review of Sister Helen Prejean’s book, The Death of Innocents [NYR, May 12], the night before conducting an oral hearing of a life-sentence prisoner in a prison in the west of England. The man, now aged forty-six, had committed a gruesome murder of his next-door neighbor’s wife, masturbating himself once the woman was dead. He was twenty-two at the time, deep in drink and self-loathing, nursing anger at his own violent upbringing at the hands of a sexually abusive father.

Now, twenty-four years later, having completed a range of challenging courses, including a sex offender treatment program, discipline, psychology, and probation staff in the prison have written a series of positive reports, recommending that he is ready to move to open prison, in preparation, maybe, two years down the line, for release on life license under probation supervision.

He is not exceptional. Each year in England and Wales some two hundred lifers are released after the tariff or punishment period of their sentence, set by a judge, has expired. At the end of the tariff period, their cases are reviewed every two years by a parole board, consisting of a judge, a psychiatrist, and an independent member, at an oral hearing to test whether they can be safely transferred from secure to open prison and from open to the community under license. The test for release is whether the prisoner still represents a risk to life and limb.

In England and Wales there are approximately five thousand lifers in prison, most of whom will be released under license; there are less than thirty lifers in the system serving a whole-life tariff. By contrast, in the United States, one in four of the 130,000 lifers in state prisons or federal institutions are serving life without the prospect of parole. The reason for this appears to be not more crime in the United States but the result of longer mandatory sentences and a more restrictive parole policy.

The irony is that most released lifers do well, get jobs, settle down with a new partner, and stay out of trouble. Why? Most have matured over a period of ten to twenty years in prison, have got themselves an education, taken responsibility for their past including the devastating impact of their homicidal behavior on the victim and his family, and are acutely aware that one false move could lead to a return to prison. Less than 2 percent of the released group commit a grave offense after release.

Containment is not enough. Whilst the truly dangerous will always need to be locked up, perhaps for a lifetime, the majority of lifers have the capacity, given the opportunity by a legislature and an informed public, to mature, face the consequences of their past, and start to lead responsible lives once more. Is Europe, or indeed England and Wales, so different in respect of what we do about the ultimate crime and punishment that we cannot learn from each other?

John Harding

Parole Board Member for England and Wales

Visiting Professor in Criminal Justice Studies, Hertfordshire University

Winchester, England

Hilary Mantel replies:

I’m indebted to John Harding for widening the terms of the debate. “Lock ’em up and throw away the key” doesn’t amount to a penal policy, and it’s dismaying to find US advocates of the abolition of capital punishment—even those who are as compassionate and informed as Sister Helen Prejean—offering the prospect of whole-life imprisonment as a kind of consolation prize to a worried public. I concede that the prospect of killers being released to kill again is terrifying, and that there will always be some prisoners who, in any jurisdiction, must never be released. But what should concern the public more immediately is that basic defects in the criminal justice system have been revealed by close examination of capital cases. Again and again, the mechanism for establishing the facts of a case is shown to be flawed. If this is true for cases where the death penalty is demanded, it is likely to be true for all homicide cases; and for lesser cases as well?

On the question of whole-life sentences, the figures John Harding quotes speak for themselves. Surely, there are very few human beings wholly incapable of redemption? At least, it seems the mark of a civilized society to think there are not. How, except by inhuman rigor, do you contain a prisoner who has no hope? What does a prison look and feel like, if it has abandoned the function of rehabilitation and is devoted only to shutting away people who are regarded as dangerous animals?

I felt tempted to add into my original review a passage which said, “there is another way of doing things,” and of course it’s the way that John Harding describes. But I didn’t want to divert from the main topic, or sound like a smug Brit. After all, there’s plenty wrong with our penal system, and we are not immune to pressure from “public opinion” whipped up by tabloid newspapers. But our judges and lawyers are not dependent on people-pleasing to keep their jobs; they don’t have to run for election and satisfy the ill-informed knee-jerk retributionists. It’s all a bit of a puzzle for democrats, I think.

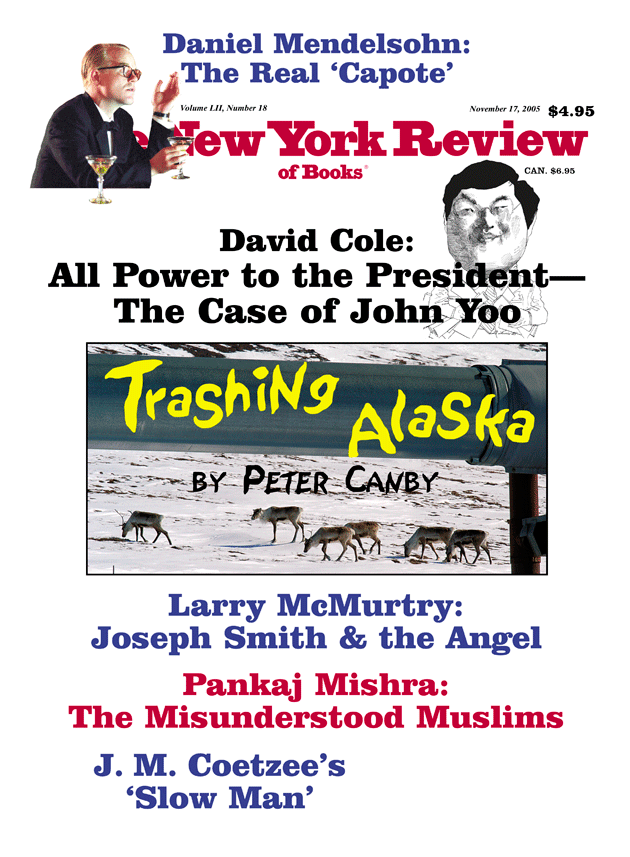

This Issue

November 17, 2005