In response to:

China: The Uses of Fear from the October 6, 2005 issue

THE CASE OF DAI QING

To the Editors:

In a review of the prison memoirs of the Chinese writer and dissident Dai Qing [“China: The Uses of Fear,” NYR, October 6], Jonathan Mirsky wrote that after her post-Tiananmen release Dai Qing’s “writing about the regime then took a different turn” and that “fear seems to explain the sad transformation in her writing,…jettisoning a lifetime’s convictions.”

We would like to set the record straight. As China specialists who have personally known Dai Qing for a long time and who keep abreast of her prolific writings, we can affirm that she did not jettison her convictions. Indeed, she remains one of the most courageous, controversial figures on the Chinese cultural and intellectual scene today.

In the years since her release from prison in 1990, Dai Qing has been a persistent proponent of freedom of speech and a critic of censorship. She has also gained an international reputation as one of China’s staunchest environmentalists. Her energetic work against China’s gigantic Three Gorges Dam has deservedly won her awards from environmental organizations around the world. For this and other courageous public efforts, she has been under house arrest more than once.

She has kept up a constant flow of writing, translating, and editing on a wide range of topics despite her work being banned in China. Under a variety of pen names (and also through essays published in Hong Kong and Taiwan and on the Chinese Internet), she continues to lambast cant and political hypocrisy in a uniquely powerful writing style that uses delicate sarcasm and irony to withering effect. Jonathan Mirsky is an admirer of her earlier writings, and he will be happy to know that she has lost none of her polemical vigor.

On an important point, both Mirsky and we ourselves disagree with a political view held by Dai Qing. She does not believe that China is ready for democracy—that is, multiparty elections to select China’s leadership. She has long been convinced that without a lengthy period of independent publishers, a decent education system, and a large, well-educated middle class, any democratic vote in China would be fatally undermined by demagoguery and corruption. She believes that until the conditions for democracy are ripe, China would be better off under an increasingly relaxed Party rule. She expressed such sentiments in her prison writings—which Mirsky presumed was a sell-out of her convictions. What he does not realize is that Dai Qing expressed such a view in writings published prior to the Tiananmen protests, just as (consistent to a fault) she holds fast to such an opinion in conversations and in her essays today.

This does not make her a toady or friend of the Party. What Dai Qing above all will be remembered for is her well-researched, truly extraordinary studies of the darker side of Communist Party history. Mirsky admiringly notes her writings in this vein from the 1980s. Again, he will be glad to know that Dai Qing continues to write and when possible publish major essays and books that dissect and confront important past episodes of Party repression, with scarcely concealed lessons for today.

In short, Dai Qing has not been scared into submission and has not betrayed her ideals. She has remained a true, effective, courageous dissenter, contrary to the impression Mirsky gained from her prison memoirs. She deserves to have this erroneous impression corrected in The New York Review’s pages.

Geremie Barmé

Jonathan Unger

The Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

Jonathan Mirsky replies:

I did not say Dai Qing had sold out. I said she was terrified into making the statements she includes in her book. I was also, as they say, careful to write at some length that until 1989 she did great work for freedom of expression. The Three Gorges essays, as I pointed out, were excellent, but were written before her time in prison. Neither in the book’s introduction nor in the edited material is this made nearly as plain as I wrote in my review.

I said that Dai Qing’s editors should have asked her if she still believed some of the things she said in the book. She called the Tiananmen demonstrations a conspiracy caused by a mastermind, “the one,” whom she never names, while also saying he had used as a mouthpiece the admirable dissident Wang Dan, who served seven years in prison after Tiananmen. She said she regretted condemning the troops for entering the square and stated that “I support the announcement of martial law and propose that the martial law troops carry out the order immediately.” This is precisely what happened.

Mr. Unger and Mr. Barmé, both well-respected China specialists, do not deal with what Dai Qing actually says in her book. They have told me they were unable to read it because almost all the copies were destroyed in a fire at the publisher’s. I am happy to learn that Dai Qing has resumed her libertarian work, but she has done herself a great disservice in Tiananmen Follies and would do well to write to the Review herself and say what she now believes. Does she still claim, as she does in the book, that she wrote “recklessly without much real thought or careful consideration…. It was exactly the kind of erroneous style of thinking that our Chairman Mao once criticized…”? Does she still promise “never again [to] involve myself with political issues nor express opinions on important matters, especially since I am no longer a Party member”?

Does she still say she acted “out of pure emotion and irrationality” and that “deep down in my heart I had forgotten all the responsibility [of being a Party member]…to protect the reputation of the government above anything else”?

I wrote that few people would have been able to stand up to what happened to her in Qin Cheng prison; any critical comment on her book should be seen in that light. But her statements in Tiananmen Follies are all the more in need of clarification following the letter of Mr. Barmé and Mr. Unger.

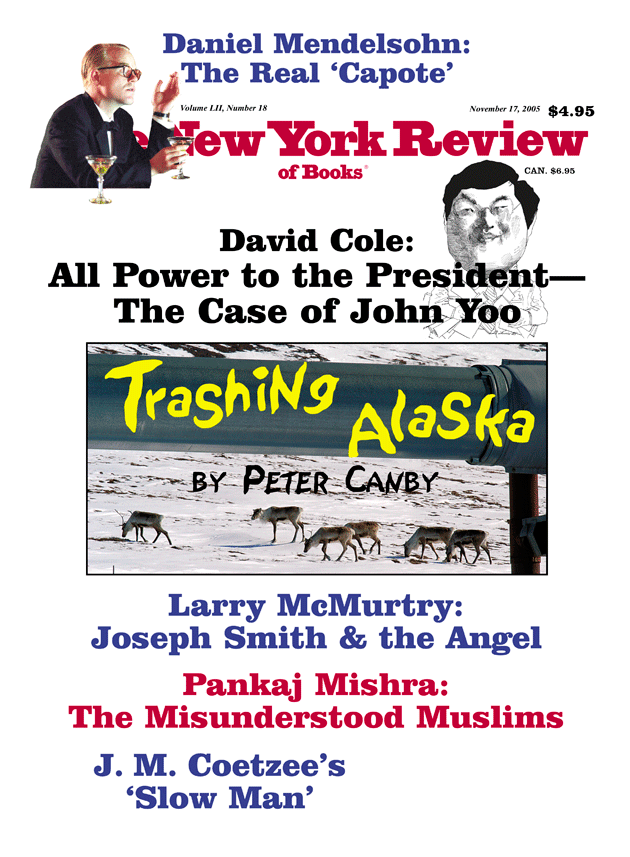

This Issue

November 17, 2005