The American political system was founded in Philadelphia, but the American nation was built on the vast farmlands that stretch from the Alleghenies to the Rockies. That farmland produced the wealth that funded American industrialization: it permitted the formation of a class of small landholders who, amazingly, could produce more than they could consume. They could sell their excess crops in the East and in Europe and save that money, which eventually became the founding capital of American industry.

But it was not the extraordinary land or the farmers and ranchers who alone set the process in motion. Rather, it was geography—the extraordinary system of rivers that flowed through the Midwest and allowed them to ship their surplus to the rest of the world. All of the rivers flowed into one—the Mississippi—and the Mississippi flowed to the ports in and around one city: New Orleans. It was in New Orleans that the barges from upstream were unloaded and their cargos stored, sold, and reloaded on oceangoing vessels. Until last Sunday, New Orleans was, in many ways, the pivot of the American economy.

For that reason, the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815 was a key moment in American history. Even though the battle occurred after the War of 1812 was over, had the British taken New Orleans, we suspect they wouldn’t have given it back. Without New Orleans, the entire Louisiana Purchase would have been valueless to the United States. Or, to state it more precisely, the British would control the region because the value of the Purchase was the land and the rivers—which all converged on the Mississippi and the ultimate port of New Orleans. The hero of the battle was Andrew Jackson, and when he became president, his obsession with Texas had much to do with keeping the Mexicans away from New Orleans.

During the cold war, a macabre topic of discussion among bored graduate students who studied such things was this: If the Soviets could destroy one city with a large nuclear device, which would it be? The usual answers were Washington or New York. For me, the answer was simple: New Orleans. If the Mississippi River was shut to traffic, then the foundations of the economy would be shattered. The industrial minerals needed in the factories wouldn’t come in, and the agricultural wealth wouldn’t flow out. Alternative routes really weren’t available. The Germans knew it too: a U-boat campaign occurred near the mouth of the Mississippi during World War II. New Orleans was the prize.

On Sunday, August 28, nature took out New Orleans almost as surely as a nuclear strike. Hurricane Katrina’s geopolitical effect was not, in many ways, distinguishable from a mushroom cloud. The key exit from North America was closed. The petrochemical industry, which has become an added value to the region since Jackson’s days, was at risk. The navigability of the Mississippi south of New Orleans was a question mark. New Orleans as a city and as a port complex had ceased to exist, and it was not clear that it could recover.

The ports of South Louisiana (POSL) and New Orleans, which run north and south of the city, are as important today as at any point during the history of the republic. On its own merit, POSL is the largest port in the United States by tonnage and the fifth-largest in the world. It exports more than 52 million tons a year, of which more than half are agricultural products—corn, soybeans, and so on. A large proportion of US agriculture flows out of the port. Even more cargo, nearly 69 million tons, comes in through the port—including not only crude oil, but chemicals and fertilizers, coal, concrete, and so on.

A simple way to think about the New Orleans port complex is that it is where the bulk commodities of American agriculture go out to the world and the bulk commodities needed for American industrialism come in. The commodity chain of the global food industry starts here, as does that of American industrialism. If these facilities are gone, more than the price of goods shifts: the very physical structure of the global economy would have to be reshaped. Consider the impact on the US auto industry if steel doesn’t come up the river, or the effect on global food supplies if US corn and soybeans don’t get to the markets.

The problem is that there are no good shipping alternatives. River transport is cheap, and most of the commodities we are discussing have low value-to-weight ratios. The US transport system was built on the assumption that these commodities would travel to and from New Orleans by barge, where they would be loaded on ships or offloaded. Apart from port capacity elsewhere in the United States, there aren’t enough trucks or rail cars to handle the long-distance hauling of these enormous quantities—assuming for the moment that the economics could be managed, which they can’t be.

Advertisement

The focus in the press and television has been on the oil industry in Louisiana and Mississippi. This is not a trivial question, but in a certain sense it is dwarfed by the shipping issue. First, Louisiana is the source of about 15 percent of US-produced petroleum, much of it from the Gulf. The local refineries are critical to American infrastructure. Were all of these facilities to be lost, the effect on the price of oil worldwide would be extraordinarily painful. If the river itself became unnavigable or if the ports are no longer functioning, however, the impact to the wider economy would be significantly more severe. In a sense, there is more flexibility in oil than in the physical transport of these other commodities.

There is clearly good news as information comes in. The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, which services supertankers in the Gulf, suffered minimal damage while Port Fourchon, which serves it, has had no damage that could not readily be repaired. Offshore oil platforms have been damaged but, on the whole, they and the oil transportation network have generally held up.

The news on the river is also far better than might have been expected. The levees on the Mississippi continue to contain the river, which has not changed its course. The levees that broke and allowed water to pour into New Orleans were on the canal side and more weakly constructed. The Mississippi has not silted up and, while the Coast Guard continues to survey the river, it appears to be fully navigable. Even the port facilities, although obviously suffering some damage, are still there. The river as a transport corridor has not been lost.

What has been lost is the city of New Orleans and many of the residential suburbs around it. As I write, most of the population has fled, leaving behind a small number of people in desperate straits. Some are dead, others are dying, and the magnitude of the situation dwarfed the inadequate resources that were made available to relieve the condition of those who were trapped. But it is not the population that is still in and around New Orleans that is of geopolitical significance: it is the population that has left and has nowhere to return to.

The oil fields, pipelines, and ports required a skilled workforce in order to operate. That workforce requires homes. They require stores to buy food and other supplies. Hospitals and doctors. Schools for their children. In other words, in order to operate the facilities critical to the United States, you need a workforce to do it—and that workforce is gone. Unlike in other disasters, that workforce cannot return to the region because they have no place to live. New Orleans is gone, and the metropolitan area surrounding New Orleans is either gone or so badly damaged that most of it will not be habitable for a long time.

It may be possible to jury-rig around this problem for a short time. But the fact is that most of those who have left the area have gone to live with relatives and friends, or are in shelters far from New Orleans. Many also had networks of relationships and resources to manage their exile. But those resources are not infinite—and as it becomes apparent that these people will not be returning to New Orleans anytime soon, they will be enrolling their children in new schools, finding new jobs, finding new accommodations. If they have any insurance money coming, they will collect it. If they have none, then whatever emotional connections they may have to their home, their economic connection to it has been severed. In a very short time, these people will be making decisions that will start to reshape population and workforce patterns in the region.

A city is a complex and ongoing process—one that requires physical infrastructure to support the people who live in it and people to operate that physical infrastructure. I don’t simply mean power plants and sewage treatment facilities, although they are critical. Someone has to be able to sell a bottle of milk or a new shirt. Someone has to be able to repair a car or do surgery. And the people who do those things, along with the infrastructure that supports them, are for the most part gone—and they are not coming back anytime soon.

It is in this sense, then, that it seems almost as if a nuclear weapon went off in New Orleans. The people mostly have fled rather than died, but they are gone. Not all of the facilities are destroyed, but most are. It appears to me that New Orleans and its environs have passed the point of recoverability. The area can recover, to be sure, but only with the commitment of huge resources from outside—and those resources would always be at risk to another Katrina.

Advertisement

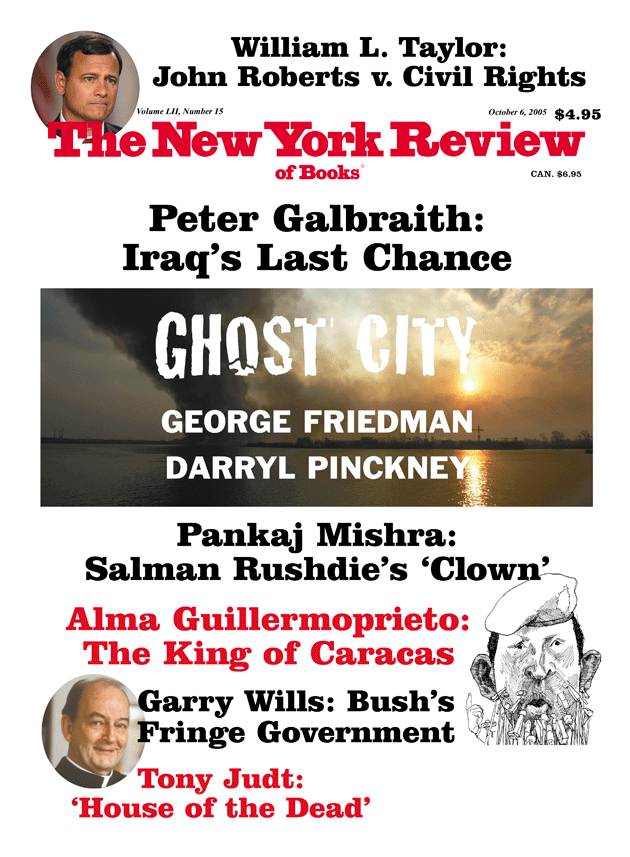

The displacement of population due to destruction, disease, and pollution is the crisis that New Orleans faces. It is also a national crisis, because the largest port in the United States cannot function without a city around it. The physical and business processes of a port cannot occur in a ghost town, and right now, except for the remaining refugees, that is what New Orleans is. It is not about the facilities, and it is not about the oil. It is about the loss of a city’s population and the paralysis of the largest port in the United States.

Let’s go back to the beginning. The United States historically has depended on the Mississippi and its tributaries for transport. Barges navigate the river. Ships go on the ocean. The barges must offload to the ships and vice versa. There must be a facility to make this exchange possible. It is also the facility where goods are stored in transit. Without this port, the river can’t be used. Protecting that port has been, from the time of the Louisiana Purchase, a fundamental national security issue for the United States.

Katrina and the events following it have taken out the port—not by fatally destroying the facilities, but by rendering the area uninhabited and potentially uninhabitable. That means that even if the Mississippi remains navigable, the absence of a port near the mouth of the river makes the Mississippi enormously less useful than it was. For these reasons, the United States has lost not only its biggest port complex, but also the utility of its river transport system—the foundation of the entire American transport system. There are some substitutes, but none with sufficient capacity to solve the problem.

It follows from this that the port will have to be revived and, one would assume, at least some part of the city as well. The ports around New Orleans are located as far north as they can be while still being accessible to oceangoing vessels. The need for ships to be able to pass each other in the waterways, which narrow to the north, adds to the problem. Besides, the Highway 190 bridge in Baton Rouge blocks the river going north for oceangoing vessels. Barges can pass under the bridge, but cargo must first be transferred to them, and for that a port is needed. New Orleans is where it is for a reason: the United States needs a city right there.

New Orleans is not optional for the United States’ commercial infrastructure. Vulnerable to inundation, it is a terrible place for a city to be located, but exactly the place where a city must exist. With that as a given, a city of some kind will return there because the alternatives are too devastating. The harvest is coming, and that means that the port, or part of it, will have to be opened soon. The port area will have to be cleared, by herculean effort if necessary. As in Iraq, premiums will be paid to people prepared to endure the hardships of working in New Orleans. But in the end, the city will return because it has to.

Geopolitics concerns permanent geographical realities and the way they interact with political life. If the logic of geopolitics prevails, it will force the city’s resurrection, even if it will be greatly changed, and in the worst imaginable place.

—September 8, 2005

This Issue

October 6, 2005