In response to:

The Custom of the Country from the June 23, 2005 issue

To the Editors:

I believe Louis Begley is too hard on Nicole Krauss in his review of her novel The History of Love [NYR, June 23]. In any case, the facts he would have her adhere to more faithfully are not as hard and fast as he imagines.

For instance, in faulting the impossibility of one of her scenarios, he writes, “It is inconceivable that a shoemaker’s daughter from Slonim in 1939 could have got the papers that would have permitted her to emigrate from Poland to the United States.”

Well, Mr. Begley, my father and grandparents, who were all peasants in Poland, did indeed get the papers that allowed them to emigrate to the United States in 1939. In fact, they left Poland on August 25, one week before the Nazi invasion.

Mark Klempner

Atenas de Alajuela

Costa Rica

Louis Begley replies:

Mr. Klempner is an oral historian, and the author, inter alia, of the forthcoming The Heart Has Reasons, a book about ten Dutch men and women who helped save Jewish children during the German occupation of the Netherlands, which according to Mr. Klempner’s Web site is to be published in the spring of 2006. According to another of his Web sites, he considers himself the son of a Holocaust survivor although, as appears from his letter concerning my review of The History of Love, and in greater detail on that same Web site, his father, two of his brothers, and their parents all left Poland for New York toward the end of August 1939. I respect the depth of Mr. Klempner’s feelings, but I disagree with Mr. Klempner’s judgment that I have been too hard on Nicole Krauss. Indeed, had it not been for constraints of space, and my own reluctance to go on cataloguing her mistakes, I might have pointed to more instances of disregard for historical truth and verisimilitude in her use of materials falling within the penumbra of the Holocaust.

Under the National Origins Act of 1924, which determined on the basis of the ethnic makeup of the American population, as shown by the 1890 census, the annual quota for immigrants from each country, i.e., the number of immigration visas that could be issued, the quota number for Poland in 1939 was 6,524, for a total population of about 35 million, including some three and a half million Jews. The Polish quota was perennially oversubscribed. Immigration visas were issued on a first-come first-served basis. The requirements for a visa were detailed and onerous, and applicants were screened by US consular officers to exclude candidates likely to become a public charge.

Among the documents a candidate was required to submit were, in addition to the visa application, birth certificate, and proof that the candidate’s quota number had been reached on the waiting list, a police certificate of good conduct, and—all important in this process—affidavits of support from two sponsors who were American citizens or permanent residents. Sponsors had to submit copies of their most recent federal tax returns, affidavits from their banks regarding their accounts, and affidavits as to the sponsors’ assets or commercial standing. Certainly it was possible to find appropriate sponsors and obtain the requisite affidavits, to file the visa application, and to reach the magic number on the waiting list, as Mr. Klempner’s grandparents manifestly did, but both the queue and the time spent in it were long.

Thus, I stand by my statement that the precipitous departure of the shoemaker’s daughter from Slonim for the United States in 1939 is inconceivable. To make it plausible, Nicole Krauss would have had to make the shoemaker father begin to “scrounge together all the zloty he had to send his youngest daughter to America” well before 1939, and he would have had to find sponsors for her not only willing to provide her with financial support, but also equally willing and able to deal with the bureaucratic red tape. The zloty would have been used for the last step in the process: the payment for the girl’s passage. However, the impression Miss Krauss conveys is different. The “shrewd” father made the decision to send his youngest daughter abruptly, sensing impending danger. There is no hint that there were family members or others in the US who would have been willing to act as sponsors for the girl or would have looked after her once she had arrived. Far from it, having arrived pregnant, she goes right to work in a dress factory, and it is “the son of her boss” who looks after her, obtains a midwife’s services, etc.

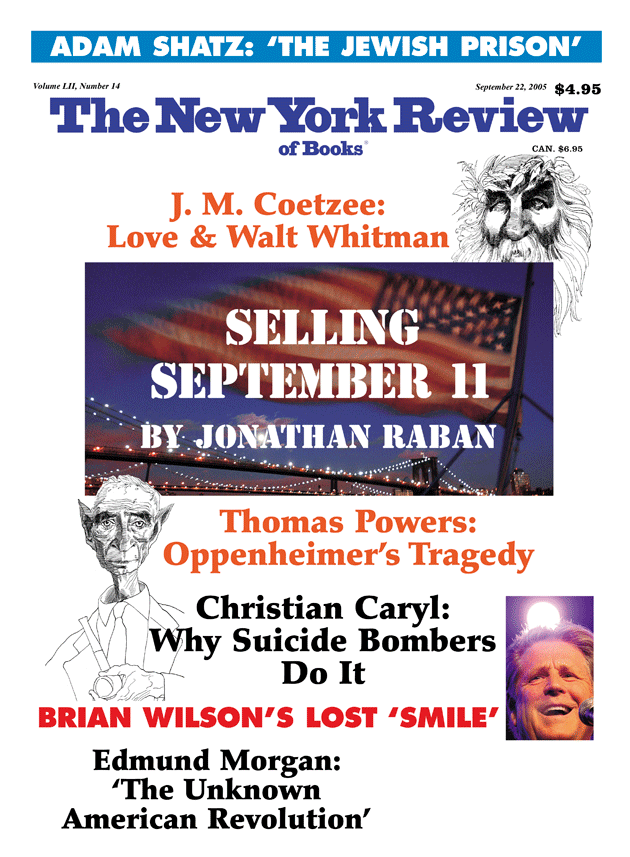

This Issue

September 22, 2005