The same paralysis occurred as Rwandans were being slaughtered in 1994. Officials from Europe to the US to the UN headquarters all responded by temporizing and then, at most, by holding meetings. The only thing President Clinton did for Rwandan genocide victims was issue a magnificent apology after they were dead.

Much the same has been true of the Western response to the Armenian genocide of 1915, the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s, and the Bosnian massacres of the 1990s. In each case, we have wrung our hands afterward and offered the lame excuse that it all happened too fast, or that we didn’t fully comprehend the carnage when it was still under way.

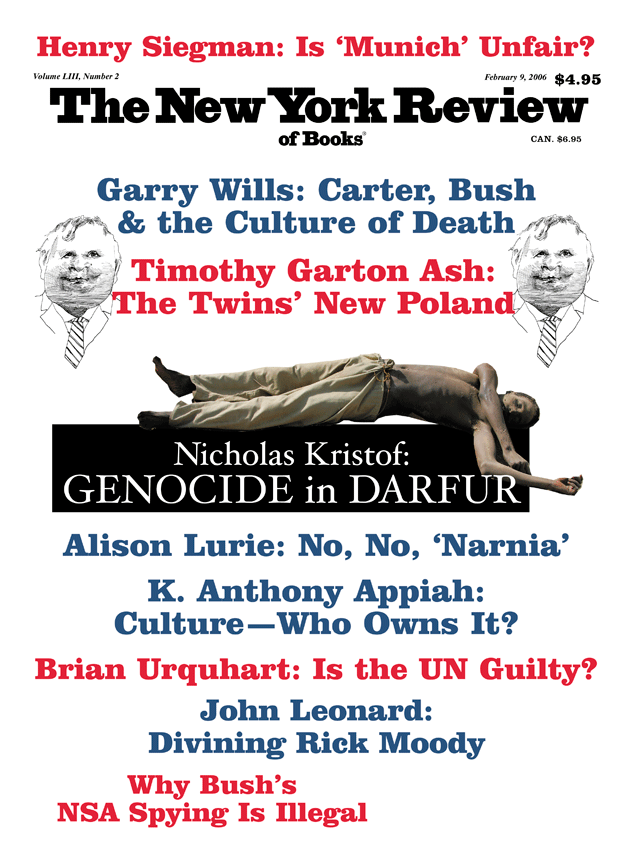

And now the same tragedy is unfolding in Darfur, but this time we don’t even have any sort of excuse. In Darfur genocide is taking place in slow motion, and there is vast documentary proof of the atrocities. Some of the evidence can be seen in the photo reproduced with this essay, which was leaked from an African Union archive containing thousands of other such photos. And now, the latest proof comes in the form of two new books that tell the sorry tale of Darfur: it’s appalling that the publishing industry manages to respond more quickly to genocide than the UN and world leaders do.

In my years as a journalist, I thought I had seen a full kaleidoscope of horrors, from babies dying of malaria to Chinese troops shooting students to Indonesian mobs beheading people. But nothing prepared me for Darfur, where systematic murder, rape, and mutilation are taking place on a vast scale, based simply on the tribe of the victim. What I saw reminded me why people say that genocide is the worst evil of which human beings are capable.

On one of the first of my five visits to Darfur, I came across an oasis along the Chad border where several tens of thousands of people were sheltering under trees after being driven from their home villages by the Arab Janjaweed militia, which has been supported by the Sudan government in Khartoum. Under the first tree, I found a man who had been shot in the neck and the jaw; his brother, shot only in the foot, had carried him for forty-nine days to get to this oasis. Under the next tree was a widow whose parents had been killed and stuffed in the village well to poison the local water supply; then the Janjaweed had tracked down the rest of her family and killed her husband. Under the third tree was a four-year-old orphan girl carrying her one-year-old baby sister on her back; their parents had been killed. Under the fourth tree was a woman whose husband and children had been killed in front of her, and then she was gang-raped and left naked and mutilated in the desert.

Those were the people I met under just four adjacent trees. And in every direction, as far as I could see, were more trees and more victims—all with similar stories.

There is no space in most newspaper articles to explain how this came to pass, and that is why the recent books under review are invaluable. The best introduction is Darfur: A Short History of a Long War, by Julie Flint and Alex de Waal. Both writers are intimately familiar with Darfur—Ms. Flint reportedly came close to getting herself killed there when traveling with rebels in 2004—and their accounts are as readable as they are tragic.

The killing in Darfur, a vast region in western Sudan, is not a case of religious persecution, since the killers as well as the victims of this genocide are Muslim. But, like the Christian and animist parts of southern Sudan, Darfur has traditionally been neglected by the Arabs (and before them, the British) who held power in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital. Flint and de Waal write that the British colonial rulers deliberately restricted education in Darfur to the sons of chiefs, so as not to produce rabble-rousers who might challenge their authority. As a result, in 1935, all of Darfur had only one full-fledged elementary school. There was no maternity clinic until the 1940s, and at independence in 1956 Darfur had fewer hospital beds than any other part of Sudan. After independence, Sudan’s own leaders nationalized this policy of malign neglect.

One result was the terrible Darfur famine of 1984 and 1985, which de Waal earlier made the subject of a powerful case study, Famine That Kills.1 That book has been reissued with a new preface because of the interest in Darfur, and it makes the point that, in places like Sudan, “‘to starve’ is transitive; it is something people do to each other.” The Darfur famine was the result not just of drought, but also of reckless mismanagement and indifference in the Sudanese government. It was transitive starvation.

Advertisement

During the 1980s and 1990s, ethnic antagonisms were also rising in Darfur. The civil war in neighboring Chad spilled over into Darfur and led some Arab tribes to adopt a supremacist ideology. Meanwhile, the spread of the Sahara desert intensified the competition between Arab and non-Arab tribes for water and forage.

The other book under review, Gérard Prunier’s Darfur: The Ambiguous Genocide, makes the point that the shorthand descriptions from Darfur of Arabs killing black Africans are oversimplified. He’s right—there has been intermarriage between tribes, and it’s hardly accurate to talk about Arabs killing Africans when they’re all Africans. The racial element is confusing, because to Western eyes, although not to local people, almost everyone looks black. And of course the very concept of an Arab is a loose one; with no consistent racial or ethnic meaning, it normally refers to a person whose mother tongue is Arabic.

But while shorthand descriptions are simplistic, they’re also essentially right. In Darfur, the cleavages between the Janjaweed and their victims tend to be threefold. First, the Janjaweed and Sudanese government leaders are Arabs and their victims in Darfur are members of several non-Arab African tribes, particularly the Zaghawa, Fur, and Masalit. Second, the killers are frequently lighter-skinned, and they routinely use racial epithets about the “blacks” they are killing and raping. Third, the Janjaweed are often nomadic herdsmen, and the tribes they attack are usually settled farmers, so the conflict also reflects the age-old tension between herders and farmers.

The leader of the Janjaweed, whom the Sudanese government entrusted with the initial waves of slaughter in Darfur, is usually said to be Musa Hilal, the chief of an Arab nomadic tribe. His own hostility to non-Arabs long predates the present genocide. Flint and de Waal quote a former governor of Darfur as saying that Musa Hilal was recorded back in 1988 as expressing gratitude for “the necessary weapons and ammunition to exterminate the African tribes in Darfur.” In the mid-1990s, the early version of the Janjaweed (with the connivance of Sudan’s leaders) was responsible for the slaughter of at least two thousand members of the Masalit tribe. In 2001 and 2002, there were brutal attacks on villages belonging to the Fur and Zaghawa tribes.

The upshot was increasing alarm and unrest, particularly among the three major non-Arab tribes in Darfur. Their militants began to organize an armed movement against the Sudanese government, and in June 2002 they attacked a police station. The beginning of their rebellion is usually dated to early in 2003, when they burned government garrisons and destroyed military aircraft at an air base.

That’s when the Sudanese government, led by President Omar el-Bashir, decided to launch a scorched-earth counterinsurgency campaign, involving the slaughter of large numbers of people in Darfur. It was difficult to use the army for this, though, partly because many soldiers in the regular army were members of African tribes from Darfur—and so it wasn’t clear that they would be willing to wipe out civilians from their own tribes. The Sudanese leadership therefore decided to adopt the same strategy it had successfully employed elsewhere in Sudan, using irregular militias to slaughter tribes that had shown signs of resistance.

This wasn’t a surprise decision. As Prunier writes: “The whole of GoS [Government of Sudan] policy and political philosophy since it came to power in 1989 has kept verging on genocide in its general treatment of the national question in Sudan.” Flint and de Waal call this “counterinsurgency on the cheap” and note:

In Bahr el Ghazal in 1986–88, in the Nuba Mountains in 1992–95, in Upper Nile in 1998–2003, and elsewhere on just a slightly smaller scale, militias supported by military intelligence and aerial bombardment attacked with unremitting brutality. Scorched earth, massacre, pillage and rape were the norm.

In other words, when Sudan’s leaders were faced with unrest in Darfur, their instinctive response was to start massacring civilians. It had worked before, and it had aroused relatively little international reaction. Among the few who vociferously protested the brutal Sudanese policies in southern Sudan in the 1990s were American evangelical Christians, partly because many of the victims then were Christians; some American evangelicals have complained to me that the American press and television are now calling attention to Muslim victims in Sudan after years of ignoring similar massacres of Christians in southern Sudan in the past. The comparison they make does not seem to me entirely convincing, but they have a point. It’s probably true that if there had been more reaction to Sudanese brutality in the southern part of the country during the 1990s, the government might not have been so quick to launch genocidal attacks in Darfur.

Advertisement

After it had decided to crush the incipient rebellion in Darfur, Sudan’s government released Arab criminals from prison and turned them over to the custody of Musa Hilal so that they could join the Janjaweed. The government set up training camps for the Janjaweed, gave them assault rifles, truck-mounted machine guns, and artillery. Recruits received $79 a month if they were on foot, or $117 if they had a horse or camel. They also received Sudanese army uniforms with a special badge depicting an armed horseman. Prunier quotes a survivor from one of the attacks that quickly followed:

The Janjaweed were accompanied by soldiers. They attacked the people, saying: “You are opponents to the regime, we must crush you. As you are Black, you are like slaves. Then the entire Darfur region will be in the hands of the Arabs. The government is on our side. The government plane is on our side, it gives us food and ammunition.”

Flint and de Waal quote a young man who hid under a dead mule and was the only survivor in his family:

[The attackers] took a knife and cut my mother’s throat and threw her into the well. Then they took my oldest sister and began to rape her, one by one. My father was kneeling, crying and begging them for mercy. After that they killed my brother and finally my father. They threw all the bodies in the well.

2.

Initially, the Sudanese government didn’t even try hard to hide what was happening. President Omar el-Bashir went on television after a massacre in which 225 peasants were killed to declare: “We will use all available means, the Army, the police, the mujahideen, the horsemen, to get rid of the rebellion.” Later, Sudan would pretend that the killings were the result of tribal conflicts and banditry, and deny that it had any control over the Janjaweed. That is false. Today, the Janjaweed and the Sudanese army work hand in hand as they have in the past.

On my last visit to Darfur, in November, while I was driving back from a massacre site where thirty-seven villagers had been slaughtered, I saw a convoy of Janjaweed. This was on a main road with soldiers staffing checkpoints, and in fact I had in my car a soldier who had demanded a ride. None of the soldiers paid any attention to the Janjaweed.

Maybe the authorities had no time to stop the Janjaweed because they were so busy trying to prevent journalists and aid workers from seeing what was happening. At one checkpoint, the secret police tried to arrest my local interpreter. They told me to drive on and leave him behind; I refused, fearing that that might be the end of him. So they detained me as well (they eventually summoned a higher commander who freed us both). It’s clear that if the Sudanese government simply applied the current restrictions on foreign journalists to the Janjaweed, the genocide would quickly come to an end.

There has been some debate over whether what is unfolding is genocide, and that’s the reason Gérard Prunier in his subtitle refers to it as an “ambiguous genocide.” The debate arises principally because Sudan has not tried to exterminate every last member of the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa tribes. Typically, most young men are killed but many others are allowed to flee.

Some people think that genocide means an attempt to exterminate an entire ethnic group, but that was not the meaning intended by Rafael Lemkin, who coined the word; nor is it the definition used in the 1948 Genocide Convention. The convention defines genocide as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such.” The acts can include killings, or injuries or psychological distress, or simply restrictions on births; indeed, arguably the Genocide Convention provides too lax a definition. But in any case there is no doubt that in rural Darfur there has been a systematic effort to kill people and wipe out specific tribes and that the killing amounts to genocide by any accepted definition.

There has also been a growing appreciation in recent decades that crimes against humanity often include sexual violence, and that has been a central fact about the terror in Darfur. Indeed, the mass rapes in Darfur have been among the most effective means for the government to terrorize tribal populations, break their will, and drive them away. Rape is feared all the more in Darfur for two reasons. Most important, a woman who has been raped is ruined; in some cases, she is evicted by her family and forced to build her own hut and live there on her own. And not only is the woman shamed for life, but so is her entire extended family. The second reason is that the people in the region practice an extreme form of female genital cutting, called infibulation, in which a girl’s vagina is sewn shut until marriage. Thus when an unmarried girl is raped, the act leads to additional painful physical injuries; and the risk of HIV transmission increases.

From the government’s point of view, rape is a successful method of control because it sows terror among the victimized population, and yet it initially attracted relatively little attention from foreign observers, because women are too ashamed to complain. As a result, mass rape has been a routine feature of village attacks in every part of Darfur, and it hasn’t yet gotten the attention it deserves.

Moreover, rape and killings are not just a one-time event when the Janjaweed attack and burn villages. Two million people have fled the villages, and most have taken refuge in shantytown camps on the edge of cities. The Janjaweed surround the camps and routinely attack people when they go outside to gather firewood or plant vegetables. In order to survive the victims must get firewood; but each time they do so they risk being raped or killed.

After a day last year of interviewing a series of women and girls who had been gang-raped outside Kalma camp, near Nyala, I asked the families why they were sending women to gather firewood, when women are more vulnerable to rape. The answer was simple. As one person explained to me: “When the men go out, they’re killed. The women are only raped.”

The Sudanese authorities initially denied that rapes were occurring, and it repeatedly imprisoned women who became pregnant by rape—saying that they were guilty of adultery. Last year, a student who was gang-raped sought treatment from a French aid organization in Kalma camp, but an informer alerted the police, who rushed to the clinic, burst inside, and arrested the girl. Two aid workers tried heroically to protect her, but the police forcibly took her away—to a police hospital where she was chained to a cot by one arm and one leg. The government also made it difficult for aid groups to bring in post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) kits, which reduce the risk of HIV in rape victims when administered promptly.

Sexual violence is also sometimes directed at men, with castrations not uncommon. At one roadblock, a mother named Mariam Ahmad was forced to watch as the Janjaweed emasculated her three-week-old son, who then died in her arms. But it is not clear that this is centrally directed policy.

Since mid-2005, Western pressure has forced the Sudan government to relent to some degree on sexual violence. It appears to have stopped arresting rape victims, and it is allowing the use of PEP kits. But as far as I can tell, rapes are continuing at the same pace as before.

3.

As dispiriting as the genocide itself is the way most other nations have acquiesced in it. You expect that from time to time, a government may attack some part of its own people, but you might hope that by the twenty-first century the world would react. Alas, that hasn’t happened. Indeed, the Armenian genocide of 1915 arguably provoked greater popular outrage in America at the time than the Darfur genocide does today.

As the killings began, the Bush administration was in a good position to take the lead. President Bush had given high priority to ending the war in southern Sudan (which is entirely separate from the war in Darfur), and he achieved a tentative peace agreement to resolve the north–south war after twenty years and the loss of two million lives. That is one of Bush’s most important foreign policy achievements, and this means that his administration—and the conservative Christians in his base—were particularly aware of events in Sudan. They were among the first to make strong statements about Darfur, and it was conservatives in Bush’s own Agency for International Development who led the way in trying to stop Darfur’s violence when it first erupted.

Yet as it turned out, the White House couldn’t be bothered with Darfur. The Democrats couldn’t either for a long time, until finally John Kerry made strong statements about the situation there in the summer of 2004. Then, perhaps worrying about his legacy, Colin Powell began taking a personal interest in Darfur. Finally, in early 2005, the Bush administration declared that genocide was unfolding in Darfur and sent large amounts of aid—but it refused to do anything more. In effect, the US had provided abundant band-aids—so that when children were slashed with machetes, we could treat their wounds. But we did nothing about the attacks themselves.

Prunier captures the situation well:

President Bush tried to be all things to all men on the Sudan/ Darfur question. Never mind that the result was predictably confused. What mattered was that attractive promises could be handed around without any sort of firm commitment being made. Predictably, the interest level of US diplomacy on the Sudan question dropped sharply as soon as President Bush was reelected….

In its usual way of treating diplomatic matters, the European Union presented a spectacle of complete lack of resolve and coordination over the Sudan problem in general and the Darfur question in particular. The French only cared about protecting Idris Deby’s regime in Chad from possible destabilization; the British blindly followed Washington’s lead, only finding this somewhat difficult since Washington was not very clear about which direction it wished to take; the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands gave large sums of money and remained silent; Germany made anti-GoS noises which it never backed up with any sort of action and gave only limited cash; and the Italians remained bewildered.

The UN has been similarly ineffectual. At one level, UN agencies have been very effective in providing humanitarian aid; at another, they have been wholly ineffective in challenging the genocide itself. That is partly because Sudan is protected on the Security Council by Russia and especially by China, a major importer of Sudanese oil. China seems determined to underwrite some of the costs of the Darfur genocide just as it did the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s. But the UN’s main problem is that it is too insistent on being diplomatic. One of the heroes of Darfur is Mukesh Kapila, the former UN humanitarian coordinator for Sudan, who almost two years ago warned: “The only difference between Rwanda and Darfur now are the numbers involved.” But UN officials were disapproving of Kapila’s outspokenness, which they saw as a breach of etiquette. And Kofi Annan, while trying to help Darfur, has been trapped in his innate politeness. He should be using his position to express outrage about the slaughter, but he seems incapable of the necessary degree of fury.

News organizations have largely failed Darfur as well—particularly the television networks. A couple of decades ago, television provided genuine news about the world; today, it mostly settles for brief and superficial impressions, or for breathless blondes reporting on missing blondes.

As a result of this collective failure, the situation in the region has been getting much worse since about September 2005. The African Union has lost some of the first troops it stationed there, a growing portion of Darfur is becoming too dangerous as a place to distribute food, and the rebels have been collapsing into fratricide. The UN has estimated that if Darfur collapses completely then the death toll there will reach 100,000 a month. Just as worrying, the instability in Darfur has crossed over into neighboring Chad. There is a real possibility that civil war will again break out there in the next year or two, and that could be a cataclysm that would dwarf Darfur.

The sad thing is that much of the suffering of Darfur seems unnecessary. The conflict there could probably be resolved. The rebels are not seeking independence but simply greater autonomy and a larger share of national resources. Neither of the books under review concentrates on how to bring the disaster to an end, but we have some good clues based in part on the peace settlement between the Sudan government and the rebels in the south. The basic lesson from that long negotiation is that Sudan’s leaders will brazenly lie about their repressive use of power, and you will get nowhere in dealings with them unless you apply heavy pressure—and you have to be perceptive about what kind of pressure will work.

In the case of Darfur, the solution is not to send American ground troops; in my judgment, that would make things worse by allowing Khartoum to rally nationalistic support against the American infidel crusaders. But greater security is essential, and the African Union troops that have been sent to Darfur are inadequate to the task of providing it. The most feasible option is to convert them into a “blue-hat” UN force and add to them UN and NATO forces. The US could easily enforce a no-fly zone in Darfur by using the nearby Chadian air base in Abeché. Then it could make a strong effort to arrange for tribal conferences—the traditional method of conflict settlement in Darfur—and there is reason to hope that such conferences could work to achieve peace. The Arab tribes have been hurt by the war as well, and the tribal elders are much more willing to negotiate than the Sudan government and the rebel leaders who are the parties to the current peace negotiations.

Flint and de Waal give a telling account of the chief of the Baggara Rizeigat Arabs, a seventy-year-old hereditary leader who has kept his huge tribe out of the war and who is quietly advocating peace—as well as protecting non-Arabs in his territory. It would help enormously if President Bush and Kofi Annan would jointly choose a prominent envoy, like Colin Powell or James Baker, who would work with chieftains like the head of the Baggara Rizeigat to achieve peace in Darfur. Such an initiative is the best hope we have for peace.

The most obvious response to genocide—strong and widely broadcast expressions of outrage—would also be one of the most effective. Sudan’s leaders are not Taliban-style extremists. They are ruthless opportunists, and they adopted a strategy of genocide because it seemed to be the simplest method available. If the US and the UN raise the cost of genocide, they will adopt an alternative response, such as negotiating a peace settlement. Indeed, whenever the international community has mustered some outrage about Darfur, then the level of killings and rapes subsides.

But outrage at genocide is tragically difficult to sustain. There are only a few groups that are trying to do so: university students who have led the anti-genocide campaign and formed groups like the Genocide Intervention Network; Jewish humanitarian organizations, for whom the word “genocide” has intense meaning; the Smith College professor Eric Reeves, who has helped lead the campaign to protest the genocide; some US churches; and aid workers who daily brave the dangers of Darfur (like the one who chronicles her experiences in the blog “Sleepless in Sudan”2 ). Some organizations, like Human Rights Watch and the International Crisis Group, have also produced a series of excellent reports on Darfur—underscoring that this time the nations of the world know exactly what they are turning away from and cannot claim ignorance.

Sad to say, one of the best books for understanding the lame international response is Samantha Power’s superb “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide3—even though it was written too early even to mention Darfur. But when you read Power’s account of international dithering as Armenians, Jews, Bosnians, and others were being slaughtered, you realize that the pattern today is almost exactly the same. Once again, the international response has been to debate whether the word “genocide” is really appropriate, to point out that the situation is immensely complex, to shrug that it’s horrifying but that there’s nothing much we can do. The slogan “Never Again” is being transformed into “One More Time.”

This Issue

February 9, 2006