1.

It is hard to experience or even think about Mozart’s The Magic Flute without a sense of wonder at how much it differs from all his other operas, ranging from The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte, the opera of choice today, to less frequently performed works such as I domeneo, The Abduction from the Seraglio, and La clemenza di Tito. Kierkegaard saw the “magic marriage” between Mozart’s genius and his subject matter in Don Giovanni; but I would argue that Mozart’s supreme dramatic work is to be found not in that fire-and-brimstone morality play but in the Masonic fable of his final year, 1791. As I wrote some time ago:

Everything we know or feel about Mozart should assure us that the inflexible view of sin and death set forth in the [Don Juan] legend must have been distasteful to him. Mozart never saw man’s will as inevitably opposed by the will of God. He conceived an essential harmony expressed by human feelings; his terms were brotherhood and sympathy and humility, not damnation and defiance. The magic marriage is The Magic Flute.1

Anyone interested in the opera has probably learned that The Magic Flute was not the outcome of some visionary initiative by the composer or the librettist. It emerged more or less naturally from the opera scene, so vital and so various, of Mozart’s time. Several different genres of Italian, French, and German opera had their day in late-eighteenth-century Vienna, among them a type of Singspiel, or German operetta with spoken dialogue, that inclined toward magic, spectacle, and fairy tale. In 1782 Vienna flocked to Ignaz Umlauf’s setting of Das Irrlicht (“The Will o’ the Wisp”), “one of the most popular fairy-tale singspiel texts of the late eighteenth century,” including “an elaborate trial scene with maidens at the temple with a prophetic fire on the altar.”2 Mozart didn’t think much of this piece, which played the Hoftheater just before his own Abduction from the Seraglio.

All the same, Das Irrlicht was to be one of The Magic Flute’s more immediate models. A few years later magic opera became all the rage when Emanuel Schikaneder took over one of the city’s suburban popular theaters. Schikaneder’s first efforts along these lines—many more came later—were Oberon, by Paul Wranitzky, a Masonic lodge brother of Mozart’s, which held the stage from 1789 to 1847, and two pieces composed by committee, a team including Mozart and several of his close associates: The Benevolent Dervish and The Philosopher’s Stone, or The Magic Island.3 Another theater countered with Kasper the Bassoonist, or the Magic Zither. These works have many dramatic and musical features that played directly into Mozart’s masterpiece. Schikaneder opened The Magic Flute in September 1791, three months before the composer died.

Schikaneder was an important theater director, a librettist, a sometime Shakespearean actor, and a star comedian. He was also a composer. He had known Mozart and his father at Salzburg about ten years earlier when Mozart had written an aria for one of his plays; a dozen years later he had the wit to conceive an opera project that might appeal to Beethoven, which Beethoven worked on and then abandoned. He was thoroughly experienced as a writer of plays and librettos, and there are some brilliant things in his conception of The Magic Flute and in his working out of the drama (as well as some less than brilliant things). Best of all was his placement of the action in the barely disguised context of Freemasonry. Some of the numbers paraphrase Masonic texts. The setting draws freely on Masonic iconography. The initiation process that consumes the opera’s second act meshes not exactly, of course, but plausibly and powerfully with the Masons’ secret rites.

Magic operas regularly featured quests and trials, with temple scenes of some solemnity, priests, and pageantry. In a stroke Schikaneder raised all of this to a new level of seriousness, contemporaneity, and, to a degree, mystery and even scandal. Since Mozart was evidently an enthusiastic Mason, and Schickaneder had been ejected from the order for his low morals, some commentators believe that Mozart himself proposed to draw on Freemasonry. In any case, Mozart was the man to capitalize on it.

2.

Schikaneder deserves all the praise he has received for the libretto—in particular, perhaps, for the climactic passages he devised for the finales at the end of each of the opera’s two acts. The two passages are roughly parallel, each bringing the lovers Tamino and Pamina together after an entire act of separation.

In Act I, the separation is literal. The two have been searching for each other aimlessly until well into the finale, when Tamino is led across the stage to meet Pamina for the first time, in the company of Sarastro—the much-talked-about and feared High Priest of Isis and Osiris, now at last before us, an imposing figure in a chariot drawn by lions through adoring crowds. Tamino has been stalking Sarastro, and Pamina has been pleading with him, but for all the attention they pay him now he might as well have been dusting the Masonic paraphernalia rather than holding court. It is extraordinary how fifteen seconds of rapturous greeting music of the simplest kind can cement the bond between these fairy-tale lovers, a bond reaffirmed hardly less simply at the parallel place in the Act II finale.

Advertisement

Though in Act II the lovers have not been literally separated, their meetings have been fraught with anxiety and grief. After surviving two of the trials set for him by Sarastro, Tamino steps up to the last and most profound one:

No fear of death shall daunt or bate me

The gates of hell already wait me;

I hear their dreadful hinges groan

My feet must dare the path alone.4

I think Tamino should indeed step up—up a little twisting path, I would recommend, leading to the gates of Fire and Water, which should have started opening by the time he turns, on hearing Pamina cry “Tamino, I must see you!” from offstage. He should have approached the gates before Pamina enters to greet him—now with the greatest of tenderness—and accompany him through the ultimate trial. As in the Act I finale, the voices merge, the personalities dissolve.

So concludes the progress of the hero and heroine, a special feature of this opera. For Edward J. Dent, whose pioneering book on Mozart’s operas from 1913 is still well worth reading today, the sense of growth and development made The Magic Flute

comparable only to the operas of Wagner. In all his operas, Mozart is remarkable for his characterization; but in none of them before this, except to a slight extent in I domeneo, did he make a single character show a gradual maturing such as we see in Tamino and Pamina. It was indeed almost impossible to do so within the limits of conventional drama. But Die Zauberflöte, although it starts as a conventional opera, very soon departs from all precedent.5

3.

The work starts with conventional fairy-tale figures. Tamino is a prince without a history. At the opening curtain, as he stumbles onstage with his empty quiver, he doesn’t even know where he is; he has shot his last arrow, and when he passes out, about to succumb to a serpent that advances toward him, he succumbs to womanhood instead, in the form of Three Ladies who arrive to save him. It is taking some time for our hero’s heroism—indeed, his masculinity—to establish itself. Mozart sees this, and writes vulnerability into Tamino’s falling-in-love song to the girl whose portrait the Three Ladies press upon him, and whose rescue the Queen of the Night so thunderously orders him to undertake—vulnerability, as well as ardor to spare.

After the Ladies slay the serpent, they want Tamino for their pleasure, but can’t agree on which of them gets the prize. Instead they take charge of his affairs, outfitting him with magic tools, a companion, and a virtual roadmap for his quest. Tamino’s dependence on women in Act I makes the first of his trials in Act II, where he must show that he can resist women, a more serious matter than might otherwise seem.

Tamino when we first see him is alone and afraid. When we first see Pamina a little later, threatened by Monastatos, “a Moor in the service of Sarastro,” she is less afraid than alarmed and very irritated. In this situation she starts explaining herself almost as a reflex, and her brief exchange with Monastatos (she sings for less than half a minute) is the first of many which relate or enact her various relationships—with him, with her mother, later with Papageno, Sarastro, and Tamino, and finally, to fill out history, her father. Her character grows richer and richer, and we end up knowing as much about her as about any of Mozart’s other grandes dames—Constanze in The Abduction, Ilia and Electra in I domeneo, the Countess Almaviva, Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, Fiordiligi, Vitellia—even though Pamina has only one aria, “Ach, ich fühl’s,” and they all have two or three.

I have a friend who has sung Tamino in various Magic Flute productions—one of them set in the New York subway—and he has little affection for the role. For the male lead never catches up with Pamina, emotionally or intellectually. His famous scene comes halfway through Act I, as he arrives at Sarastro’s temple and attempts to confront the evil abductor, as he thinks, of his lady love. In an exceptionally long accompanied recitative he disputes with a strange Speaker he meets at the temple door, a priest of Sarastro’s order. It is the first serious musical moment in an opera which will introduce more and more of such moments over its course. As Tamino blurts out one question and answer after another, we hear the generic prince growing into a person. He seems like a little boy: enthusiastic, impetuous, tactless, insecure, uncertain how to respond, quick to despair.

Advertisement

But a tenor can do only so much with a recitative of this kind, however excellent it is. While he can hardly fail to get it across adequately, he has somehow to avoid being overshadowed by the baritone, a deeper role in every respect. (A little later Tamino will find himself upstaged by forest animals.) Paternal, sometimes severe and sometimes sympathetic, the Speaker is in no position to enlighten Tamino, only to try to make him think. This is a wonderful small role for the right singer—Willard White, for one, in an old video of David Hockney’s first Magic Flute at Glyndebourne.6

Ingmar Bergman’s much-loved version of The Magic Flute, from 1973, makes expert use of the small stage of the restored eighteenth-century Swedish Court Theater at Drottningholm.7 In the temple scene, however, Tamino moves through the temple door on stage into a half-lit room with a low fire in the grate, where he stands like a schoolboy in front of the bespectacled Speaker, seated at a desk. After much talking at cross purposes the Speaker makes his final pronouncement and gets up to go, leaving Tamino by himself, to think for himself. “O everlasting night, when will you end?” he says. The Speaker has blown out his lamp. Reading Mozart in his own way, Bergman has turned this moment into one of revelation. In fact, all Tamino can really think of at this point is his continuing commitment to Pamina, and in fact, it’s all he needs.

In an early (and persistent) variant text of The Magic Flute, Tamino says “o dunkle Nacht,” rather than “o ew’ge Nacht“—darkened night, rather than everlasting night. I wonder if Bergman knew this. It looks as if someone were tinkering with the libretto, to make it less redundant (for the Speaker has used the word ewig in his previous pronouncement), more elegant (dunkle rather than dunkel), and perhaps also a little more sensible (if night is everlasting, why ask immediately when it will end?).

This variant text has been known about for almost as long as the opera has existed, but it remains a puzzle.8 While sometimes it seems to improve the libretto, at other times it produces little more than elegant variation, and at others it makes an uncanny fit with the music—a better fit than is the case with the regular text.9 Consider this not unimportant place in the Act I finale, just before the lovers come together before Sarastro. Pamina apologizes for her attempted escape from his realm. She explains that Monastatos tried to take advantage of her. Sarastro answers:

Arise, take courage, my loved one! For without having to draw it out of you, I know more about your heart. You love another deeply.

Here the music takes a brief but striking melancholy turn, as Sarastro repeats the words for emphasis:

You love another deeply. I will not force you to love [Ich will dir nicht zur Liebe zwingen], yet I will not allow you to leave.

The variant text gives Sarastro a personal stake in the action that is only hinted at in the canonic text:

…I know more about your heart. It harbors no love for me, no love for me [es ist für mich von Liebe leer: accent on mich]. I will not force you to love, yet I will not allow you to leave.

With these words and Mozart’s melancholy music, Sarastro becomes a less hieratic, more human figure as soon as he opens his mouth—and also one with a clearer message. Although you do not return my love any more than you return the love of Monastatos, he says, I will not force myself on you as he has—just as in Act II he will tell Pamina that although the Queen of the Night has sworn revenge on him (and ordered Pamina to kill him), he will not reciprocate. Revenge has no place within diesen heil’gen Hallen, any more than rape.

4.

Returning to Tamino, and how he fails to catch up with Pamina: the scene with the Speaker at the temple door is followed by one of the libretto’s less happy inventions. Lacking any obvious course of action, Tamino takes up the magic flute he has been given by the Three Ladies and plays, hoping to summon up Pamina. Instead his music attracts the Peaceable Kingdom animals beloved by stage directors and audiences alike—to speak only of the Metropolitan Opera, Marc Chagall’s airborne shtetl beasts, the cute critters of David Hockney, or the great spirit bears kited across the proscenium by Julie Taymor in last (and this) year’s production.

Schikaneder saw the need to demonstrate the flute’s power in Act I as a prelude to its more epochal demonstration in Act II. Like Orpheus’ lyre, the flute first charms wild beasts and later brings man past death and back again (as shown in the opera’s trial of Fire and Water). Important as all this may have been to Masons, I think the reason it leaves me unimpressed goes beyond a general feeling that The Magic Flute suffers from a surfeit of symbolism. For one thing, Tamino and Pamina surely owe their success at the trials to their own virtue, especially Pamina’s, rather than to magic. Another thing is the fitful action of the flute-playing scene itself. Tamino grows sad when the flute fails to produce Pamina (Bergman’s fluffy animals gather around and hug him). Then he becomes somewhat hopeful again. It was clever to have his flute answered by Papageno’s panpipe, and charming, but the music is not Mozart’s best.

The role of Tamino wilts further in Act II, after he submits to initiation into Sarastro’s order. For until the climactic moment at the gates of Fire and Water, he spends his time enduring trials to which Schikaneder allows him no musical response. Not only does the libretto deny him arias or even recitatives, for much of the time Tamino is sworn to silence, than which for an operatic character there is no state more conducive to emasculation. Tamino is forbidden to communicate with Pamina; after her famous lament, “Ach, ich fühl’s” (“hearts may break”), he has nothing to say or do except listen to Papageno mocking the action. One of the places I most cherish in the Bergman film—another is the intermission, of course, with the dragon (Mozart’s serpent) trotting around backstage—comes at the end of “Ach, ich fühl’s.” When the singing is over, the orchestra has a few bars of doleful music echoing her cry “See, Tamino, Tamino, Tamino, Tamino, Tamino.” The camera pans away from her to Tamino, who is covering his face and silently weeping.

Meanwhile, while Tamino appears stuck throughout Act II, whether musically or in the libretto, Sarastro and the order are portrayed more and more fully and beautifully, as is also the personality of Pamina. Since Pamina cannot submit to the official trials, which exist for men only, Schikaneder contrived less formal tribulations for her that are parallel and much more intense. She too must reject the wiles of women—a major motif in this opera, like it or not. One may be tempted to cut the little misogynist duet sung by the Two Priests—

Be on your guard for Woman’s humors:

That is the rule we follow here.

For often Man believes her rumors,

She tricks him, and it costs him dear.

She promises she’ll never hurt him,

But mocks his heart, that’s true and brave;

At last she’ll spurn him and deceive him:

Death and despair was all she gave.

—but it has a function in the music drama, dignifying by music what has been spoken in the dialogue many times. The Queen of the Night’s berserk demand that her daughter kill Sarastro shocks Pamina into disillusion and drives her to attempt suicide. Then in her suicide scene, observed by the Three Boys—a scene that is half comic, half excruciating, and astonishingly original—she faces death alone, in a moment of protracted grief.10 Compare Tamino’s manly if mindless reaction at the gates of Fire and Water.

Again, Pamina does not undergo the official quasi-Masonic trials—at least, not before the last of them. Her initiation is central to the drama, surely, but since the initiation of women was a sensitive matter, Schikaneder probably had good reason to soft-pedal it. “Am I allowed to speak to her?” Tamino asks, when he hears Pamina calling offstage as he approaches the final trial. Yes, say the guardians of the gates, the two Armed Men:

A woman who fears neither Night nor Death

Is worthy and will be initiated.11

By this time Pamina has already survived her own trial of death, so she can naturally lead Tamino now. The voices merge and the souls, as I have said, dissolve into one another. Woman leads, yet man plays the flute, and it is music from the first scene in the opera—his scene—that haunts the unearthly flute music as they pass through the Fire and Water.

So Pamina takes her place with Tamino among the elect. There was a debate at the time about the initiation of women as Masons, and some say Schikaneder and Mozart can be seen as taking sides in favor of women in that debate. Look at it this way: magic fairy-tale operas often had scenes of trials and initiation and moral uplift, as has already been noted. By underpinning The Magic Flute with Masonic lore and reference, its authors transcended this sort of generic idealism so as to present what was for them the best contemporary vision of a humane order. But Pamina brought with her imperatives of her own, and by the time they were through, they had developed a humane vision that transcended that of eighteenth-century Freemasonry.

5.

Dr. Johnson’s indelible definition of opera as an exotic and irrational entertainment predated the significant operas of Gluck, let alone those of Mozart. For Gluck, in theory as in practice, opera was art, not entertainment, dramatic even when it was exotic (as in his Iphigenia in Tauris), and as rational as can be possible for an art that lives on music. Mozart admired Gluck, and stylistic and technical characteristics of his music drama certainly found their way into I domeneo and Don Giovanni, if not The Magic Flute. But Gluck is a frame of mind, someone has said, rather than a congeries of musical forms and styles, and Gluck’s spirit hovers over all the “serious” numbers in The Magic Flute, however different their styles: Tamino’s recitative with the Speaker, the choruses and marches of the priests, Sarastro’s aria, the chorale fugue sung by the Armed Men, and the march for the trial of Fire and Water. Mozart was pleased when Salieri came to a performance and loved it, insisting that the piece was no low-class amusement but an operone, a grand opera. Salieri was a pupil of Gluck.

Still, Dr. Johnson’s view has prevailed, for The Magic Flute in particular, if not for opera in general. Almost everyone is happy to think of The Magic Flute as a combination of sublime music and irrational plot. One can see why. For all its strengths, the libretto takes full advantage of the license it enjoys as a fairy tale, the license to blur continuity, consistency, coherence. The role of Papageno, written for the great comic ad-libber who was running the show—Schikaneder—wears thin today, especially since the singers who tend to be cast in it are not really very funny. The role can be cut down a good deal without diminishing its function in the drama; Bergman showed that. Nor is the case for rationality helped by setting the opera on the Broadway–7th Avenue Line or in the new terrain of the Lion King, up on ground level. Or in a sanatorium, with Sarastro as the head psychiatrist, the concept behind last year’s Paris production.

I prefer activist productions that combine sublime music with the plot smoothed and coaxed to make it less irrational, as in the Bergman film, and also in the translated version that W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman made in 1956. Such efforts require some violence to the original text—too much violence in the Auden version, which unfortunately is now almost forgotten. Not so the film, which recently came out on DVD: a continuing challenge to purists. True, it is not well sung, but connoisseurs must remember that the original Papageno was not a singer of the caliber of Wolfgang Brendel or Bryan Terfel. Tinkering with the libretto in order to clarify the action is a small matter that should raise no hackles; many directors do it. As Auden remarked, years ago, even as he complained mildly about

Director Y who with ingenious wit

Places the wretched singers in the pit

While dancers mime their roles, Z the Designer,

Who sets the whole thing on an ocean liner,

The girls in shorts, the men in yachting caps,

Yet genius triumphs [Auden added] over all mishaps.12

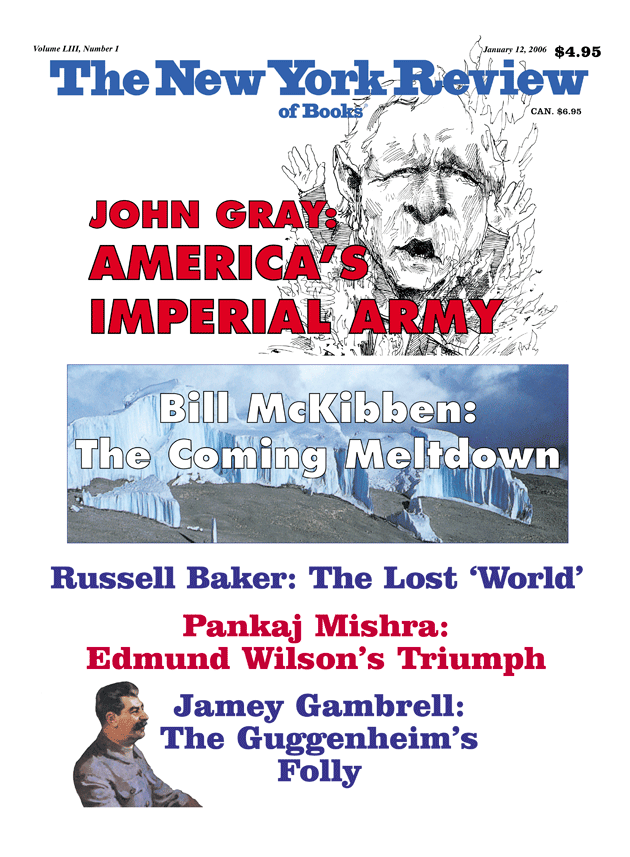

This Issue

January 12, 2006

-

1

Opera as Drama, revised edition (University of California Press, 1988), p. 104. ↩

-

2

David J. Buch, “Die Zauberflöte, Masonic Opera, and Other Fairy Tales,” Acta Musicologica, Vol. 76, No. 2 (2004). For more on the background and much else about the opera, see the Cambridge Opera Handbook by Peter Branscombe, W.A. Mozart: Die Zau-berflöte (Cambridge University Press, 1991). ↩

-

3

Both operas have been recorded, very handsomely, by the Boston Baroque, conducted by Martin Pearlman: Telarc CD–17279 (rec. 2001) and CD–80508 (rec. 1998), respectively. ↩

-

4

From the version of The Magic Flute prepared for NBC television fifty years ago, at the bicentennial of Mozart’s birth, by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, reprinted in W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman: Libretti and Other Dramatic Writings by W.H. Auden, 1939–1973, edited by Edward Mendelson (Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 177. I draw on the same translation below. ↩

-

5

Mozart’s Operas, second edition (London: Oxford University Press, 1949), p. 262. ↩

-

6

With Felicity Lott, conducted by Bernard Haitink (Video Arts International). ↩

-

7

Criterion Collection DVD (2000). ↩

-

8

See Michael Freyhan, “Toward the Original Text of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte,” Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 39, No. 2 (1986), pp. 355–380, and “Rediscovery of the 18th Century Score and Parts of ‘Die Zauberflöte’…,” Mozart-Jahrbuch 1977, pp. 109–148. C.A. Vulpius, a Weimar man of letters, prepared a more thorough overhaul of the original text for the local première in 1794, to the irritation of Schikaneder, but it never gained currency. Vulpius was the brother of Goethe’s mistress Christiane Vulpius; Goethe’s unfinished sequel to The Magic Flute dates from around the same time. ↩

-

9

Michael Freyhan believes these places show that the variant text must be the one actually set by Mozart—especially since he can make the case that it originated in Vienna in the year of The Magic Flute, 1791. But he cannot explain how, if Mozart set the variant text, the canonic text appears in both his autograph score and the libretto printed in 1791. ↩

-

10

It was a winning idea, incidentally, to introduce the Three Boys as rather cold figures uttering maxims, and then turn them into caring spirits who act. They rescue Pamina and later Papageno. ↩

-

11

“Ein Weib, das Nacht und Tod nicht scheut,/Ist wurdig und wird eingeweiht.” It has always seemed odd to me that Tamino and Pamina should appeal to the Armed Men, heraldic figures. An early illustration for this scene includes two priests, who would be more natural interlocutors (see Branscombe, W.A. Mozart: Die Zauberflöte, p. 188; one priest carries what looks like an initiation hood for Pamina). ↩

-

12

See W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman: Libretti, p. 155. ↩