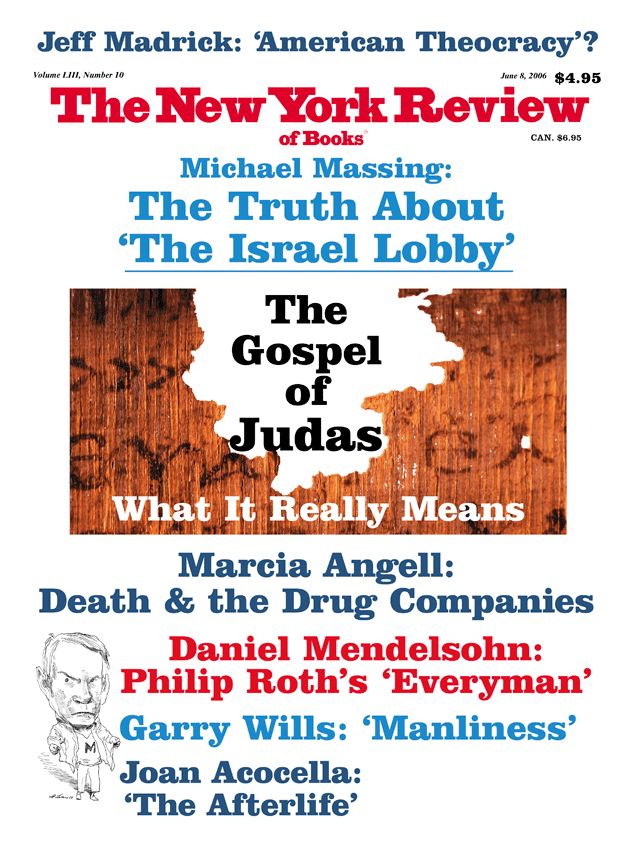

The Gospel of Judas, released to the public for the first time in April, is one of the most important contributions to our sources for early Christianity since the discovery of thirteen papyrus codices near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. Those fourth-century manuscripts, probably buried by monks from the nearby monastery of Pachomius, contained Christian writings originally dating from the second and third century CE. Condemned as heretical by bishops such as Athanasius of Alexandria, they were excluded from the New Testament canon and disappeared from Christian history without a trace, save for having been denounced in the polemics of early writers on heresy. Often referred to as the Gnostic gospels, these texts have most recently attracted much attention as one of the sources of inspiration for Dan Brown’s controversial novel The Da Vinci Code. Quite apart from their sensationalist appeal, however, writings including the Gospel of Mary and Gospel of Thomas have provided scholars with an unprecedented opportunity to expand our understanding of early Christian controversies over such issues as gender, heresy, and church leadership.

Like the Nag Hammadi texts, the recently uncovered Gospel of Judas survives in a third- or fourth-century papyrus codex and is written in Coptic, the ancient language of Egyptian Christianity (though scholars believe the original was in Greek). It was first discovered in the 1970s by some Egyptian peasants in a burial cave near the village of Qarara in Middle Egypt. Probably searching for the ancient treasures that the sands of Egypt still occasionally yield, they stumbled across a skeleton wrapped in a shroud, with a limestone box lying beside it. Inside was a cache of papyrus manuscripts whose true importance would not be recognized for another thirty years.

The gospel was badly damaged in its long journey from the darkness of that burial cave near the Nile to its recent publication. One of the manuscript dealers who purchased it and then tried to resell it kept it for some years in a bank vault in Hicksville, Long Island, causing deterioration. Another dealer put the gospel in a freezer, damaging it further. By the time the renowned Swiss papyrologist Rodolphe Kasser got hold of it in 2001, it was in a heartbreaking condition. In an essay published with the recent edition of the gospel, Kasser recalls that he let out a cry when he first saw it:

It was a stark victim of cupidity and ambition. My cry was provoked by the striking vision of the object so precious but so badly mistreated, broken up to the extreme, partially pulverized, infinitely fragile, crumbling at the least contact.

Enlisting the help of Florence Darbre, chief restorer at the Bodmer Foundation in Switzerland, Kasser undertook the painstaking task of putting the codex back together. Each of the fragments had to be fitted together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Not only the shapes of the fragments but also the individual fibers had to be matched. Darbre used a powerful microscope to view fibers so fine they were invisible to the naked eye. Only then could Kasser proceed with the transcription and translation of the Coptic script. Fiber by fiber, then letter by letter, a story unread for over 1,500 years began to unfold, although a considerable number of gaps remain in the text, which was finally issued this year under an exclusive arrangement with the National Geographic Society.

The figure of Judas, notorious for his heinous yet indispensable act of betrayal, personifies the paradoxes of evil: Why does a good and omnipotent God allow evil things to happen, and if they are part of the divine plan, how can human beings justly be held accountable for them? In the New Testament accounts, Jesus’ famous prediction sums up the problem, while leaving it unresolved:

For the Son of Man goes as it is written of him, but woe to that one by whom the Son of Man is betrayed! It would have been better for that one not to have been born.

(Mark 14:21; cf. Matthew 26:24and Luke 22:22)

Luke goes further than the other two gospel writers in exploring the motivations of Judas’ act, attributing it to possession by Satan (Luke 22:3); but in so doing, he actually deepens the paradox, making the devil responsible in some sense for the salvation of humanity. John’s account is the most complex, suggesting that Judas was possessed by Satan at the instigation of Jesus himself:

Jesus answered ‘The one who will betray me is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread….’ Then dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas Iscariot, son of Simon. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.

(John 13:26–27)

The Gospel of Judas puts a different emphasis on the insistence of previous gospel writers that Jesus had foreknowledge of his death and consented to it. In the Gospel of Judas, not only Jesus but also Judas was in on the secret mission.

Advertisement

Written decades after the canonical gospels, perhaps around 140 CE, the Gospel of Judas does not provide a basis on which to reevaluate the historical Judas. But it raises the question of why a second-century Christian would be interested in rehabilitating Jesus’ archenemy. What would inspire a writer to produce this particular response to the enigma of the betrayal, recasting the infamous traitor as Jesus’ most loyal disciple and rewriting the Christian story in his name? Many second-century Christian texts claim to record secret revelations given to eminent apostles, such as Peter and John, or to other figures known to have been close to Jesus, like Mary Magdalene. By contrast the author of Judas apparently commits what must have been seen as a subversive act by associating his gospel with a figure already stigmatized among ancient Christians. This must have been a carefully considered choice. One possible explanation for this decision is that the author of Judas was part of a Christian group that had been attacked by the leaders of his church, ostracized, and perhaps cast out altogether. He may have been a victim of escalating attempts to exclude those who dissented from the bishops and to brand them with the newly developing label of “heretics.” For a community of people attacked as apostates and traitors, the rewritten story of Judas could have provided a way to reinterpret their experience, and to present themselves not as outcasts from the Christian faith but as its most loyal and misunderstood defenders. In fact, Irenaeus, the second-century critic of heresy who is our earliest witness to the Gospel of Judas, suggests that the community of Christians who read this text indeed conceived of themselves as misunderstood and identified not only with Judas but also with other vilified figures from the Bible, such as Cain. While such a reconstruction of the situation of the author must remain speculative, it would make sense of what might otherwise seem a bizarre choice of patron saint.

2.

Scholars have commonly approached such noncanonical texts as the Nag Hammadi writings by assuming that they presuppose a particular worldview known as Gnosticism. In the newly published edition of the Gospel of Judas, Marvin Meyer and Bart Ehrman both use this approach to interpret the text. Summing up one of the basic tenets of Gnosticism, as he understands it, Ehrman writes: “This world is a cesspool of pain, misery, and suffering, and our only hope of salvation is to forsake it.” The cosmos, in this view, is the evil creation of a malevolent lower being, who created humans by trapping sparks of divinity in material bodies; but not everyone has this “divine spark,” and only those predestined few who do can be saved. Salvation is not a matter of faith or of ethics, however, but of acquiring spiritual knowledge—gnosis. Finally, according to this interpretation of the Gnostic gospels, Jesus’ death has no part in the salvation of humanity, except as an example of how death releases the true self from the body: “In the Gospel of Judas, as in other gnostic gospels, Jesus is primarily a teacher and revealer of wisdom and knowledge, not a savior who dies for the sins of the world.”

None of these beliefs is explicitly set out in so-called Gnostic texts, as Ehrman has freely admitted elsewhere,1 nor do we have any evidence that the authors of these works considered themselves to be “Gnostics,” rather than just Christians. Instead, the Gnostic credo is the construction of modern scholars, who have compiled it in part by drawing on the polemics of such critics of heresy as Irenaeus, and in part by creating a synthesis of ideas found in the various Nag Hammadi writings as well as other texts. Such scholarly categorizing can, of course, be useful, and there is no doubt that certain elements of the tenets of “Gnosticism” can be found in some of the Nag Hammadi texts, as well as in the Gospel of Judas itself. However, presupposing a “Gnostic worldview” when approaching these non-canonical texts creates several major, and related, problems. The most obvious is that much gets read into the texts that is not actually there. Another is that the differences between the individual texts become muted, while their differences from the canonical writings are highlighted. This has led to a view of the Nag Hammadi texts as a kind of “anti-canon,” a mirror image of the New Testament (“Christianity turned on its head” as Ehrman describes Judas), when it is more productive to view all these early Christian texts as differing positions in the same debate, discordant voices in the same conversation.

The text is identified on the first page as “The secret account of the revelation that Jesus spoke in conversation with Judas Iscariot” shortly before the days leading up to Passover, when Judas collaborated with the Jewish authorities. The gospel begins by telling us:

Advertisement

When Jesus appeared upon the earth he performed signs and great wonders for the salvation of humanity, because some were walking in the path of righteousness and others in the path of their transgression. Now the Twelve were called as disciples, and he began to speak with them about the mysteries above the world and those things which will happen at the end.2

The gospel is then divided into three scenes. In the first scene, Jesus comes upon the twelve disciples as they are sitting together, giving thanks over their bread, and he laughs. They ask why he is laughing at their thanksgiving, saying they have “done what is right,” and he replies that he is not laughing at them, but that they are doing the will of their God. Confused, they reply that he is the son of their God; but he tells them, “Truly I say to you, no race of the people that are among you will know me.” When they heard this, “the disciples became angry and infuriated and began blaspheming against him in their hearts.”

What does Jesus mean by apparently dissociating himself from “their God”? As the editors of the Gospel of Judas point out, we can understand Jesus’ remarks in the light of similar texts from Nag Hammadi. These attempt to explain the imperfect nature of our world by attributing its creation not to the true God but to a lower, malicious divinity, identified with the God of Israel. Later the Gospel of Judas gives us more detail about its cast of cosmic characters, but at this point, Jesus’ comments make it clear that the disciples are mistakenly worshiping an inferior being rather than the highest god, an accusation that understandably upsets them. Recognizing their indignation, Jesus issues a challenge: “Let any one of you who is strong enough among human beings bring out the perfect human and stand before my face.” The text continues:

They all said, “We have the strength.”

But their spirits did not dare to stand before him, except for Judas Iscariot. He was able to stand before him, but he could not look him in the eyes, and he turned his face away.

Judas said to him, “I know who you are and where you have come from. You are from the immortal realm of Barbelo. And I am not worthy to utter the name of the one who has sent you.”

Barbelo, according to some Nag Hammadi texts, is the divine virgin mother and the partner of the true God. By identifying Jesus as from the “realm of Barbelo,” Judas makes it clear that he alone understands who Jesus is and that he has been sent by the highest divinity. Jesus is impressed enough with Judas’ spiritual perceptiveness to take him aside for special revelations: “Step away from the others and I shall tell you the mysteries of the kingdom. It is possible for you to reach it, but you will grieve a great deal.” Judas then asks when Jesus will tell him these things, but Jesus leaves, keeping Judas—and the reader—in suspense.

In the second scene, Jesus appears to the disciples again and when they ask where he went when he left them, he replies, “I went to another great and holy race.” His disciples are once again confused and ask, “Lord, what is the great and holy race, exalted above us, which is not in these realms?” Jesus laughs and replies, “Why are you thinking in your hearts about the strong and holy race? Truly I say to you, no one born of this realm will see that race.” The word for “race” here is translated by the editors of the gospel as “generation,” but “race” is in fact a more natural translation and fits with both Jewish and early Christian descriptions of themselves as a race or a people.

The disciples are again understandably upset at Jesus’ seemingly dismissive words—are they not to be a part of the holy people?—but worse criticism of them is still to come. They ask Jesus to interpret a vision they have had, in which they saw twelve wicked priests making sacrifices at an altar:

Some sacrifice their very own children, others their wives, all the while praising and behaving with humility toward one another; some sleep with men, some murder, some commit many sins and transgressions. The people who are standing over the altar are invoking your name.

Jesus’ interpretation is less than flattering to the disciples:

It is you who were conducting the services at the altar that you saw. That god is the one you serve, and you are the twelve men whom you saw. The animals you saw being brought as sacrifices, this is the crowd whom you are leading astray upon that altar.

Here the critical portrayal of the twelve disciples draws on ambiguities that are already apparent in the canonical gospels, developing them in new directions. In the New Testament, after all, the disciples frequently come across as rather dim, petty, and fickle; they misunderstand parables, fall asleep in the garden of Gethsemane, and disown Jesus as he faces death. Even so, the resurrected Jesus ultimately bestows authority on them and in the end they become faithful missionaries of his message. By the second century, the apostolic succession—the doctrine that religious authority had been passed on from the apostles through an unbroken succession of bishops—was well established, and bishops claimed to have inherited their authority directly from the disciples, excluding Judas of course. The extremely negative depiction of the apostles in the Gospel of Judas (which only increases as the text continues) along with the elevation of Judas, the one disciple whom church authorities did not claim as their forebear, must therefore have been intended to criticize the bishops themselves. After all, if the bishops’ authority was inherited from a group of people who had worshiped the wrong god and had never learned Jesus’ secret teachings, it was surely illegitimate.

If the twelve disciples do indeed stand for the bishops who claimed apostolic authority, what could the text mean by suggesting that they were leading the crowd astray like sacrificial animals upon an altar? It seems likely that this is a criticism of the bishops’ endorsement of martyrdom, and the consequent acceptance by early Christians of execution by the Roman authorities. The author of the Gospel of Judas apparently views martyrdom as a vain sacrifice, and blames the church leaders for leading their sheep-like congregations to the slaughter. The editors miss this aspect of the Gospel of Judas, translating the text as saying: “This is the crowd whom you are leading astray before that altar.” However, the Coptic literally says “upon.”

By the second century, the risk of death at the hands of the authorities was very real for Christians, as Christianity was held in deep suspicion by many people in the Roman world. To those who believed that the peace and prosperity of the empire depended on divine good will, Christians’ refusal to honor the gods and their repudiation of ancestral traditions seemed to endanger society as a whole. The Roman authorities were particularly suspicious of a cult that encouraged its members to opt out of participation in the festivals and rituals that were central to the public life of the empire, and to do so in favor of secretive meetings in private houses. Such behavior seemed to many people inexplicably withdrawn from society, and hostile to it.

Despite these perceptions of the Christian religion, the prosecution of its members in the second century was sporadic and aimed principally at attempting to get Christians to change what were seen as antisocial practices and not at physically punishing them. Generally, to escape conviction on the charge of being a Christian, a member of the church had to deny his or her faith and make a gesture of willingness to participate in worship of the Roman gods, for example by sprinkling some incense on an altar. Roman judges often gave Christians numerous opportunities to recant before finally sentencing them to death. But many church leaders, for example the second-century bishop of Antioch, exhorted their congregations not to avoid martyrdom, but rather to embrace it. Recalcitrant Christians were held up as glorious examples to others; the idea that martyrs were participating in Jesus’ passion made suffering something to be not only endured, but desired. Ignatius of Antioch, for example, writing to the church in Rome as he is escorted there to face death, implores the congregation not to use their influential connections to save his life:

Allow me to be eaten by the beasts—that is how I can reach God; I am God’s wheat and I am ground by the teeth of wild beasts that I may be found pure bread of Christ…. Pray to Christ for me, that by these means I may become a sacrifice.

As this quotation suggests, the imagery of martyrdom as sacrifice became a powerful way for Christians to identify themselves with Christ. In their view, the martyrs were reenacting Jesus’ death, which they believed had been a sacrifice on behalf of all humanity. The author of the Gospel of Mark symbolically interprets the bread and wine consumed at the Jewish feast of Passover as Jesus’ body and blood, the “blood of the covenant which is poured out for many” (14:22–25). The Gospel of John makes this symbolic point even more strongly by readjusting the timing of the crucifixion, so that it takes place not on the day after Passover, but on the day of the Passover meal itself: Jesus thus becomes the sacrificial lamb.

However, despite the monolithic picture of early Christians’ willingness to die at the hands of the authorities that we have inherited from martyrologies and much other literature, not to mention such movies as The Sign of the Cross, martyrdom was in fact a controversial issue at the time. Some Christians objected to what they saw as a pointless waste of life, and they believed that public confessions of faith were unimportant. One of the texts found at Nag Hammadi, The Testimony of Truth, expresses this opinion. Like many of the Nag Hammadi writings, it is somewhat fragmentary, but the point its author is making is clear enough:

The foolish, thinking in their heart that if they confess “We are Christians,” in word only but not with power, while giving themselves over to a human death, not knowing where they are going or who Christ is, thinking that they will live while they are really in error, hasten toward the principalities and the authorities.

Here the principalities and authorities that are referred to may be those of the Roman Empire; or they may be demonic powers who hold sway over the world. While we don’t know much about the people who wrote and read this text, it is likely that they believed inner commitment was what mattered. In the same way that Paul advised the Corinthians that it was acceptable to eat meat sacrificed to the pagan gods, because they didn’t really exist, these Christians may have felt that publicly renouncing their beliefs and taking part in sacrificial rites was not a betrayal as long as one privately maintained one’s personal commitment to the Christian faith.

The Gospel of Judas seems to express a similar attitude toward martyrdom; but rather than criticize the martyrs themselves, it implicitly blames the bishops as wicked priests who are invoking Jesus’ name, yet offering their followers up like dumb animals on the altar of a false god. Just as in the first scene, in which Jesus laughs at the disciples because their thanksgiving rituals are directed toward the wrong god, here too he criticizes the apostles and, by implication, their successors the bishops as misunderstanding what the true God wants:

For it has been said to the human races, “Behold, god received your sacrifices through the hands of priests,” that is, the servant of error. But it is the Lord—he who is the Lord over the All—who commands that they will be judged in the last days.

This criticism of the apostolic authorities should be read as presenting a contrast with the ultimate sacrifice of Jesus. As we shall see, the culmination of the gospel is Jesus’ special commission to Judas to “sacrifice that man that carries me”: in other words to offer up the human part of Jesus in death. Through the imagery of the wicked priests and their false sacrifices, Judas implicitly points to the perfection of Christ’s sacrifice. Moreover, by identifying the priests who appear in the disciples’ vision with the apostles and, by implication, with the leaders of the apostolic church, he is also turning some of the commonplaces of anti-Jewish rhetoric, used by the “orthodox” bishops themselves, against the apostles. Early Christians often denigrated traditional Jewish sacrificial ritual as inadequate and “fleshly” rather than spiritual, and argued that Jesus’ death had superseded it. The New Testament Letter to the Hebrews, for example, says:

For if the blood of goats and bulls, with the sprinkling of the ashes of a heifer, sanctifies those who have been defiled so that their flesh is purified, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to worship the living God!

(9:3–14)

Later Christians, such as Melito, the second-century bishop of Sardis, took these ideas even further, arguing that the sacrifices made by the Jews had merely been a symbol of what was to come in the person of Christ.

The theology of the Gospel of Judas appears to share these conceptions, but draws out their logical implications much further, suggesting that the bishops are hypocrites; they preach that Jesus was the final and perfect sacrifice, while they exhort their followers—even their wives and children—to offer themselves up as human sacrifices in martyrdom. According to the Gospel of Judas, the bishops are just like the Jewish priests they criticize, erroneously worshiping an inferior god, rather than the transcendent one who no longer required sacrifice of any kind.

In the final scene, the other disciples are no longer present and we reach the climax of the gospel, in which Jesus reveals to Judas the secrets of salvation and the universe. This part of the gospel offers the most difficult interpretative challenges to the modern reader, filled as it is with mythological references and complex cosmologies. First, the recurrent idea of the “holy race,” and Judas’s relation to it, is elaborated in some detail. Judas tells Jesus about a vision he has had:

I saw myself in the vision, and the twelve disciples were stoning me and persecuting me greatly…. I saw a house…and its size my eyes are not able to measure…. And in the middle of the house there was a crowd…. Teacher, receive me also with these people.

Jesus’ reply seems discouraging: “No one born of mortal man is worthy to enter the house which you saw, for that is the place kept for the holy ones…. Behold, I have told you the mystery of the kingdom.”

Judas becomes anxious at this: “Teacher, surely my seed is not subject to the rulers?” The editors of the gospel assert in a footnote that “seed” here refers to “the spark of the divine within” but this interpretation is unnecessary. This phrase “divine spark,” which appears over and over again in Ehrman’s commentary, never once appears in the gospel itself. “Seed” here would be more naturally understood in its usual sense of Judas’ offspring, or the seed from which he comes. Judas’ question seems to be about whether he and his progeny are subject to the demonic powers who hold sway over the world. Jesus tells him:

You will become the thirteenth and you will be cursed by the rest of the races and you will rule over them. In the last days they will condemn your turning upward to the holy race.

Judas will be cast out from the community of the Twelve; but in the end he will join the holy race and rule over everyone else, including his former adversaries.

At this point, Jesus is ready to unfold the deepest mysteries of life to Judas. He tells him how the true God, called the great Invisible Spirit, created the universe through a series of emanations of lights and angels, which then vastly multiplied. To modern readers this may all appear dizzyingly esoteric, but an ancient reader familiar with Greek astronomy and science would have understood it as an illustration of how the heavens exist in perfect numerical harmony and balance. One of the angelic beings, Jesus says, created a figure called Adamas. It is this heavenly Adamas who creates the “race of Seth,” that is, the holy race about which we have heard much in this text.

In ancient Judaism and Christianity, a reference to the race of Seth symbolically designated membership in the group of God’s righteous people who descended from Seth, the good son of Adam and Eve, who, as Genesis tells us, was given to them by God to replace Abel, whom Cain murdered. And since the “race of Seth” was thought to have preexisted in the heavenly realms, it meant that all those who belonged to it on earth had their true home in Heaven.

At this point, the Judas gospel introduces the reader to another realm beneath the heavens, called “the realm of Chaos and the Underworld.” This is where our own world is located. A heavenly power summons the angels Nebro and Saklas to rule over it. It is these angels who create the material bodies of Adam and Eve, using the form of Adamas as a blueprint. But while these lower beings create the humans’ bodies, it is the transcendent God, as the Gospel of Judas explains, who gives them spirit and soul.

Presupposing the “Gnostic” myth in which the creator is wicked, Ehrman assumes that, in the Judas gospel, our world is the handiwork of the fallen angels Nebro and Saklas. But in fact the Gospel of Judas introduces “the realm of Chaos and the Underworld” as if it had always existed. Nebro and Saklas don’t create Chaos; God appoints them to rule over it, in an act of divine providence that extends order throughout the universe. However, as Ehrman stresses, the Judas gospel gives a negative portrayal of the cosmic rulers, despite the fact that they have been commissioned by God; Nebro’s face is described as “spewing forth fire” and “his likeness was [defiled] with blood.” Moreover his name, we are told, means “rebel.” But the theme that rebellious angelic powers rule the world is hardly unique to so-called Gnostic theology. The Gospel of John, for example, describes the devil as “the Prince of this world”; and the Epistle to the Ephesians proclaims that “our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness” (6:12). Like Satan, whom the Gospel of Luke tells us Jesus saw “fall from heaven like lightning” (10:18), the figures of Nebro and Saklas give the author of the Judas gospel a way of explaining evil in the world as somehow both independent of, yet ultimately subject to, a perfect God.

When we consider the extensiveness and detail of cosmological description in this text, we can understand why the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik found it unappealing in a recent review:

“The Gospel of Judas” turns Christianity into a mystery cult—Jesus at one point describes to Judas the highly bureaucratic organization of the immortal realm, enumerating hundreds of luminaries—but robs it of its ethical content. Jesus’ message in the new Gospel is entirely supernatural. You don’t have to love thy neighbor; just seek your star.3

Gopnik is right that the Gospel of Judas is very different from those that were included in the canon; but part of that difference is a matter of genre. As Gopnik himself points out, Judas is not a gospel in the sense that we have come to understand the term, as a narrative of Jesus’ life on earth; rather it takes a particular episode from the familiar story and explores its implications. The dizzying cosmological myths of these texts may not easily engage the sympathy of those of us used to a more earthy Christianity of the manger and the shepherd, of parables and miracles of ministering to the poor, but they were no less part of a struggle to answer the perennially troubling question, Unde malum?: Where does evil come from?

The understanding that this gospel gives its readers of themselves is complex. Its theology of good and evil is far from a simple, world-hating dualism; one could argue, for example, that it presents a more nuanced universe than the New Testament Gospel of John, with its stark images of darkness and light, divinity versus the devil. The Gospel of Judas teaches its readers that they were created by inferior angels, yet in the divine image of perfect humanity; that they have the potential to reclaim their authentic heavenly identity, and also the potential to die without ever realizing who they really are. Salvation in this text is certainly related to knowledge and revelation, but it is also a matter of ethics. In fact, Judas makes it clear at the beginning that Jesus’ mission on earth is to save humanity because “some were walking in the path of righteousness and others in the path of their transgressions.” Specific acts are singled out as immoral throughout the gospel, including murder, homosexuality, improper ritual observance, and endorsement of martyrdom. Further, we should all aspire to be members of a race repeatedly described as pious or holy (not wise or “Gnostic”).

At the end of the initiation of Judas into the mysteries of the universe, Jesus returns to the theme of sacrifice, apparently once again condemning in a few barely legible lines those who offer sacrifices to Saklas, the cosmic ruler. Then he finally gives Judas his special mission: “But you yourself will be greater than all of them, for you will sacrifice the man who carries me.” It seems strange to deny the significance of this sacrifice as dismissively as Ehrman does: “In [the New Testament] view, Jesus’ death was all-important for salvation…. Not so for the Gospel of Judas.” For Ehrman, the fact that the gospel doesn’t include a crucifixion scene demonstrates that Jesus’ death was not central to the theology of Judas. But when we consider that the entire text revolves around an interpretation of the events leading up to Jesus’ death, this omission is more convincingly explained by the fact that the events of the crucifixion were assumed to be already familiar, and the author of Judas had no wish to dispute them. What he was concerned to convey to his readers was a different explanation of how and why the crucifixion came about.

Unfortunately, the text at this point is frustratingly fragmentary, but Jesus’ final words to Judas are legible:

And the image of the great race of Adam shall be lifted up, because before heaven and earth and the angels, that race existed throughout the eternal realms. Behold, you have been told everything. Lift up your eyes and see the cloud and the light within it, and the stars surrounding it. And the star that leads the way, that is your star.

These enigmatic lines suggest that more than Jesus’ return to the heavenly realm depends on Judas’ actions; the salvation of humanity is indeed at stake. Judas’ star will lead the other stars, or souls, into the luminous cloud where the heavenly Adamas and his holy race dwell. Judas accepts his divine commission: “[He] lifted up his eyes and saw the luminous cloud and entered it.”

Now that its important points have been made, the gospel switches tone abruptly and ends with the following brief and relatively prosaic lines:

Their high priests murmured because he [i.e., Jesus] had gone into the guest room for his prayer. But some scribes were there watching carefully in order to arrest him during the prayer, for they were afraid of the people, since he was regarded by all as a prophet.

They approached Judas and said to him, “What are you doing here? You are Jesus’ disciple.”

Judas answered them as they wished. And he received some money and handed him over to them.

The text has deposited us unceremoniously back in the narrative territory of the canonical gospels; but after witnessing Judas’ visions, this once-familiar landscape will never look the same again.

The Gospel of Judas is unlikely to shake many Christians’ faith in the traditional account of Jesus’ betrayal and crucifixion, but it does provide us with a sophisticated meditation on the relationship between God and evil—one that was perhaps inspired by personal experience as much as philosophical curiosity. (After all, the experience of being demonized—as the author may have been—would understandably lead an early Christian to rethink the problem of evil.) The answers that this author came up with are far removed from the clichés of Gnostic dualism. In fact, by bringing Judas into the fold, this text actually ends up domesticating evil, at least in implying that the greatest betrayal can turn out to be an act of pious obedience. How convincing, or satisfying, we find such an interpretation is another question altogether. In the end, to quote Bob Dylan’s song, it’s up to us to decide “whether Judas Iscariot had God on his side.”

This Issue

June 8, 2006

-

1

See, e.g., The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 173. ↩

-

2

All translations of the Gospel of Judas are by the authors and in some cases differ from the recently published translation. ↩

-

3

See The New Yorker, April 17, 2006. ↩