In response to:

How To Read Elfriede Jelinek from the July 19, 2007 issue

To the Editors:

Tim Parks has done an admirable job introducing the readers of The New York Review to 2004 Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek’s translated novels [“How to Read Elfriede Jelinek,” NYR, July 19]. By necessity, this focus presents less than half of Jelinek’s works.

As specified by the Nobel Commission, she was honored for “her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays….” Her texts for the theater (over a dozen prior to the committee’s decision) are widely acknowledged as pioneering what is now known as “postdramatic theater” (by definition something to be avoided by American mainstream theater).* They have been staged in pathbreaking productions by leading directors at the most prestigious theaters in Germany and Austria. In tandem with her novels Jelinek’s plays are vital to the appreciation of her linguistic strategies in the staging of the cultural drama inside language.

Aside from the practical, commercial reasons for the absence of productions of her plays in translation, their omission in Tim Parks’s discussion—even as a passing reference to her major works for the stage—reflects a prevailing attitude in Anglo-American criticism toward drama as separate from, if not inferior to, “literature.”

For the record, Greed, though the last novel published before the Nobel decision, was preceded by a far more “ambitious,” “difficult,” and substantial work: The Children of the Dead, which is widely acknowledged as Jelinek’s magnum opus. (The American translation of the 666-page novel, to be published by Yale University Press, is currently in progress.)

Finally, a translator’s quibble: durchhalten is not the standard German for suppressing a bowel movement. It would be zurückhalten (holding back)—a parental admonition every German-speaking child remembers from long car rides with the family. Characteristically, Jelinek distorts a mundane idiom for a deliberately childish pun in tune with senility that suggests the generation that was exhorted by Hitler to durchhalten—“stand fast”—at Stalingrad. (Nazi propaganda plays and films intended to inspire the populace to “stand fast” are called Durchhaltestücke, stand-fast-plays.)

In that context it would be worthwhile to further examine the meaning of provincialism in literature. Historically this has been a problem of translatability of some of the most brilliant Austrian writers from Ferdinand Raimund and Johann Nestroy to Karl Kraus, Elias Canetti to H.C. Artmann, Ernst Jandl and the Vienna Group—whose texts satirize the performative force of local habits of speech. It should be remembered that Wittgenstein turned to Nestroy for the motto of his Philosophical Investigations: “And anyway, the thing about progress is that it looks much bigger than it really is.”

Gitta Honegger

Arizona State University

Tempe, Arizona

Tim Parks replies:

My thanks to Gitta Honegger for this generous response and above all for her elucidation of the use of durchhalten in the pun that I looked at as an example of translation problems in Jelinek’s novel Greed. I had, of course, consulted German friends when suggesting that this was a standard phrase for suppressing bowel movement, but the pun is no doubt richer and more scathing as described by Honegger. This reinforces my suggestion that translation struggles to deliver the density of cultural reference for which Jelinek is famous. In answer to my quizzing him on this issue, the excellent Michael Hulse, who has translated two of Jelinek’s novels, remarked: “There’s a dense wordplay or deft pun or neologism in every sentence. The linguistic ingenuity is dazzling in the German. My translation can’t hold a candle to it.”

It is true that I discussed only the five novels available in English, the film adaptation of Jelinek’s most famous work, The Piano Teacher, two long interviews (one by Honegger), and a “dramatic dialogue” (translated by Honegger), mentioning one of the plays in passing. This was not because of any prejudice against the theater but due to the difficulty of getting hold of copies of Jelinek’s work in the languages I read well (English and Italian) and above all to the lack of opportunity to see any productions of her plays. Honegger will recall that my review of her biography of Thomas Bernhard included a consideration of his plays and above all of her cogent argument that they were so dense with allusion to Austrian history, Austrian theater, and even the backgrounds of the particular actors for whom parts were written that it was unlikely that anyone from outside Austrian society would be able to appreciate them fully.

This partly explains why outside the German-speaking world Bernhard is mainly admired for his novels. Again this hardly seems to be the result of a prejudice against drama. Samuel Beckett, for example, is best known internationally for his plays despite having written some of the most extraordinary novels of the twentieth century. In any event, the idea that a literary tradition that still recognizes Shakespeare as one of its greatest forefathers would disparage drama tout court seems improbable.

Advertisement

In the case of Jelinek it is evident from descriptions of her plays that they are very immediately engaged in an ongoing political struggle in Austria and exploit what Honegger herself has referred to as “the histrionic excesses of the tortured Austrian psyche.” It may be that while the radical positions Jelinek assumes and her tone of unnuanced denunciation make sense within the dynamic of Austrian public life, outside Austria and in translations that lose the original texts’ linguistic richness, they come across as merely shrill. Certainly that was my feeling with many of her novels and since the plays are largely made up of long blocks of prose, rather than dialogues, it seems unlikely that they will escape this problem.

One of the presumptions behind globalization is that every work of narrative and dramatic art can be immediately and profitably translated into every language. All my own work on translation (see particularly my book Translating Style) suggests that for some authors the context of the original language and society remains supremely important and makes international comprehension unlikely. I would not describe this as “provincialism” if only because such writers address at the very least a national audience. I certainly would not see it as negative, but rather as something to savor, a guarantee that culture has not become uniform and monolithic. It does however present serious problems for those who award international prizes for literature.

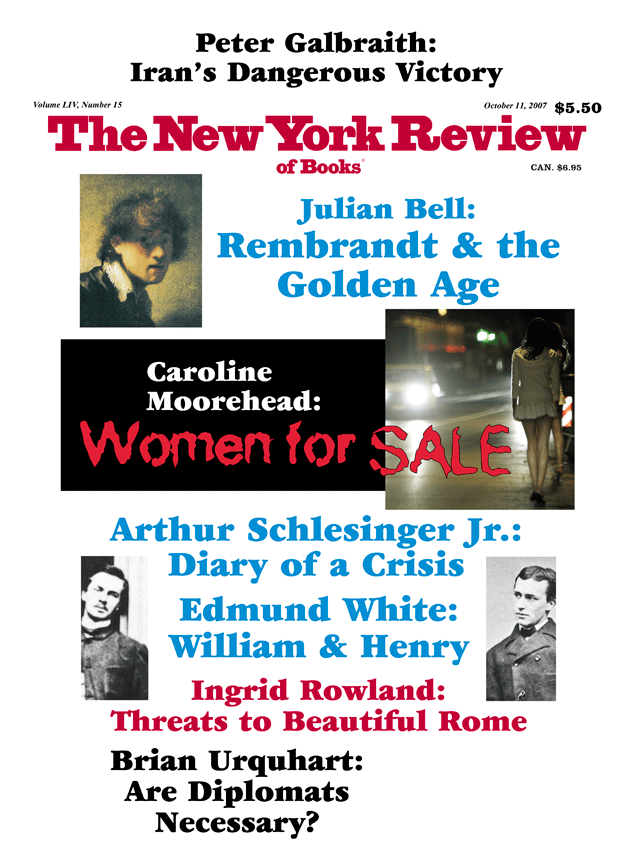

This Issue

October 11, 2007

-

*

Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatic Theatre (Routledge, 2006). ↩