The question of literary borrowing is a vexed one, to the point that academe had to invent a fancier name and call it intertextuality. Walter Benjamin famously longed to write a book consisting entirely of quotations from the works of others, and almost achieved that ambition in The Arcades Project, his gigantic study of Paris in the nineteenth century, though the thing is probably too much of a ragbag to be considered a book in any proper sense. But at what point does petty pilfering become indictable plagiarism? As lofty an arbiter as T.S. Eliot was blithely tolerant in the matter, remarking that “immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.”

Michael Krüger is a highly experienced man of letters, being a publisher and editor, a novelist, and a renowned poet. He is the head of the distinguished German publishing house Carl Hanser Verlag, edits the literary magazine Akzente, and has published three novels and a collection of poems in English translation. If one is to judge by The Executor, first published in 2006 under the title Die Turiner Komödie, the rigors of his day job have soured him somewhat on the business of writing in general and of fiction writing in particular:

I have never quite been able to imagine what might induce a person to become a professional writer. I can understand someone writing the occasional poem…. But when someone early in life, after dropping out of, or, in rare cases, actually completing, a university course in literature or business then makes the decision to spend his or her adult life making up cops-and-robbers tales, or stories that are cannibalizations of the author’s own life, that, it seems to me, is an act of sheer recklessness.

In the wittily titled novel The End of the Novel his protagonist goes even further, declaring that “too many books existed in this world,” and bitterly observing that “writing a novel was in any case a business for dubious minds which had to fit their few ideas into a framework since otherwise they would be lost in the night of history.”1 In The Cello Player (Die Cellospielerin), the composer-narrator, who is not exactly a rock of dependability himself, sardonically remarks of his friend Günter that he “suffered from the illness, apparently common to many writers, of being unreliable.” With a publisher like this, who needs critics?

The narrator of The Executor, whom we know only by the initial “M.,” is a German in his sixties, a printer by trade and an unsuccessful writer, who has come to Turin after the death by suicide there of his best friend, the world-famous expatriate novelist Rudolf:

In the last few years of his life, Rudolf had written four short novels that earned him literary prizes, honors, and a great deal of money. He was translated into every conceivable language: he even received author’s copies from Korea. Yet with every award his general frame of mind worsened and his hypochondria and pessimism bloomed.

In his will Rudolf has appointed M. to be his literary executor. This proves a poisoned chalice, which is not inapt, since it was M., as we learn later in the narrative, who supplied Rudolf with the “very specific vegetable poison” that he used to kill himself.2 Rudolf’s suicide is presented as the inevitable and banal consequence of his life, and M. is not exactly grief-stricken by his friend’s going—he seems more than anything else annoyed by the executorial burden that Rudolf has loaded on him. The reader will share in M.’s equanimity, for Rudolf is one of the most dedicatedly splenetic, duplicitous, and treacherous misanthropes to be found outside the pages of Samuel Beckett or Louis-Ferdinand Céline, or Rudolf’s own favorite, the Elias Canetti of Auto-da-Fé.

As M. had feared, matters in Turin are complicated. Rudolf has left a vast mass of papers, including, most importantly, the scattered texts of what he intended to be his magnum opus, entitled The Testament, a “gigantic work, his fiery meteor, [which] would encompass all humanity’s hidden, forgotten, discarded knowledge…. ‘My Faust,’ he would say on the telephone with a laugh….” Although Rudolf’s descriptions of this work lead M. to think it must be something like a “large-scale, multipart essay,” Rudolf considers it a novel—indeed, he intends it to be his, and the world’s, last novel:

In a single great flash of brilliance, he meant to transform the genre itself and at the same time illuminate human nature in general through the singularity of his characters, after which double-lightning strike he would lapse quietly into his usual fog of despair. He had long been abnormally pessimistic about the future of our civilization and its culture, and since the more playful aspects of literature did not present enough of a challenge for him he felt that his final work must produce an ultimate salvation for mankind—something that was lacking in the intellectual output of the times. He spoke of fuel for the soul, inner self-illumination, using these pyromaniacal images to describe the explosion of literary fireworks that would be his last gift to the reading, thinking world.

Rudolf had been living for twenty years in Turin, where he held a professorship in a seemingly unspecified discipline—“He had always made a great mystery of this appointment”—and was handed over a palazzo in which to set up his Institute for Communications Research, in which, if his wife is to be believed, “there was not much communicating happening…let alone research.” On the floor above the institute is the penthouse apartment where Rudolf lived, on the terrace of which is assembled his menagerie of assorted wild and domestic animals—Rudolf’s zoo is one of the richer sources of comedy in this quirkily and lugubriously comic little book. It is in this penthouse that M. lodges as he attempts the task of sorting Rudolf’s papers; he even sleeps in Rudolf’s bed, sharing it, though this is not certain, with Marta, Rudolf’s assistant and self-proclaimed lover.

Advertisement

These domestic arrangements are highly bizarre—M. seems to loathe and fear Marta, yet he has no sooner arrived at the apartment than a relationship is instituted between them that seems to be as intimate as the one that Marta insinuates she enjoyed, if that is the word, with Rudolf. M., like all of Krüger’s fictional protagonists, is contemptuous, rueful, stubborn, put-upon, a hapless Candide who has long since given up believing in Doctor Pangloss’s nostrums; he is also constantly at the mostly untender mercies of the Ewig-Weibliche.

Marta, it turns out, is only one side of the romantic quadrangle drawn up and carefully maintained by Rudolf. There is also Rudolf’s neglected wife Elsa, now in the hospital dying of cancer but still possessed of all-important legal powers over her late husband’s papers. And there is Eva, one of Rudolf’s supposed former girlfriends, whom Rudolf had always spoken of with savage disparagement and whom M. believed he had broken with decades before. Now, however, among the boxes of letters from Rudolf’s readers, admirers, and chance lovers, M. comes upon, to his consternation and bafflement, a long and intimate correspondence between Rudolf and Eva—“love letters, despite their curiously dry tone.” From these letters M. learns that right up to Rudolf’s death Eva had been planning to leave her husband and set up with Rudolf in an autumnal romantic union. Along with this revelation comes another, from M. himself, who informs us, with what we suspect is a forced offhandedness, that he too had conducted a brief liaison with Eva in the far past, during a year M. had spent living in Rome.

There are matters here deeper than the complicated love relationships and unhappy fates of a couple of aging littérateurs and their women. Krüger might laugh as bitterly as Rudolf certainly would at the suggestion that The Executor is at any profound level concerned with the unromantic fate of Germany in the second half of the twentieth century. Yet despite the heavy emphasis the book lays on the literary, or anti-literary, and erotic aspects of Rudolf’s life, we also learn, by default almost, that from his newfound literary earnings he had been contributing to various unspecified political movements, of which persuasion we are not told, and that in his student days at the Free University of Berlin, center of West German student activism in the late 1960s, he had been a prominent cultural-political firebrand of the far left, engaging in “endless talk about the cataclysmic changes that must revolutionize the study of German literature.”

Of all this overheated radicalism, not insignificantly, M. is a disenchanted observer, having “decided that the revolution everyone talked of was stupid and dishonest.” Judgments such as this send us back to The Cello Player and the trips made by that book’s narrator to Budapest before 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union:

I liked going to Budapest best of all…. When the young Western pedants put their theories on display there, they were met with bitter irony. Our French colleagues, in particular, were made to suffer. No matter how much effort they invested in harmonizing electronic music with the demands of dialectical materialism, their sole reward would always be laughter. One brief but hearty laugh.

It is not too much to read Rudolf’s bitterness and pessimism as the result, to some degree at least, of the disappointed hopes of the 1960s generation of activists who were convinced they were going to bring about “cataclysmic changes” that would transform the world and usher in a new era of freedom, tolerance, and peace. “It can’t turn out well if we focus on ourselves too intensively,” Rudolf would say to M. during their protracted telephone conversations when Rudolf was in exile in Turin, perhaps acknowledging that the cult of the self that the Sixties engendered was one of the chief causes of the collapse of those millenarian hopes of the Age of Aquarius. In the depths of his rancor and self-loathing Rudolf, however, harks back to the flawed giants of a previous generation, such as Brecht, and Louis Althusser, and even Günter Grass, all of whom would understand M.’s essential question, as he delves into Rudolf’s mounds of paper: “Can what is real be contained in documents…?”

Advertisement

The Executor, like the others of Krüger’s novels mentioned here, is soaked in a sense of shame and shaming futility. M. says of his own books that they were “doomed by my weariness and my constant sense of shame—a lifelong deep shame at saying anything at all, at making anything public.” There is throughout a Beckettian sense of the incommensurate effort of artistic creation, of the writer “obsessed with detail, slaving away at an ever growing mound of paper,” who in the end “is forced to admit that even in his own estimation all he has produced is nonsense.”

As to the struggle with the intractability of language, there is in The End of the Novel a passage—which is, ironically, both beautiful and expressive—which might have been lifted straight from Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Chandos Letter:

In my description of nature I had tried to convey the impression pure, without comparison, as it were without gloss, to leave it its unfathomable dignity, but whenever I remembered details of my account, of how I had tried, a hundred times, to put the rain down on paper, to describe the noise, the light over the suddenly darkening fields, I despaired over the actual realization, over the paltry words which had to be assembled into long periods in order to capture the simplest things.

Krüger’s, or at least Krüger’s narrator, feels most sharply for the writer and his plight, since the painter and the musician, so he holds, have it easier. A painter “can become a darling of modern-art specialists by spreading broad smears of paint over some great image of Western art,” and a composer can “snatch his first laurels with a variation on a theme of Zemlinsky or Bach.” The writer, however, should he attempt early success “by simply replacing the nouns he didn’t care for in Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus,” or offering a variation on the ending of The Man Without Qualities, “would be laughed out of town.” And while he is being laughed at, he is suffering his own inward lacerations: “The public has no idea that writing is a disease, and that the writer who publishes is like a beggar who exhibits his sores.”

Rudolf, it turns out, has betrayed everyone, himself, his wife and lovers, his friend M., and even, or especially, the writers whom all his life he has read, revered, and whose transcendent achievements he has thoroughly absorbed. At least, it all seems a betrayal. The Testament, Rudolf’s Faust, his “fiery meteor,” is in the end revealed as what he says it is, his “monster.” It is nothing more—or as Walter Benjamin would say, nothing less—than a compendium of passages from countless works of world literature in half a dozen languages which the polyglot Rudolf has been reading, annotating, and excerpting throughout his life.

The manuscript of the book, titled variously The Testament, The Torino Comedy, A Novel, is a folder of fifty-odd pages. There are two epigraphs, one from Maurice Blanchot, from his famously moving meditation on the “last writer,” the other some lines of verse by Cesare Pavese, another of Turin’s eminent suicides, concluding with: “We’ll go down into the maelstrom mute.” The rest is a series of directions—“Yellow notebook, 1963, pp. 20–24. Box 16,” etc.—to be followed for the assemblage of thousands of quotations that will constitute the finished work. There is also a letter from Rudolf to M., giving him permission to compile and publish the book, or burn the blueprint, as he thinks best. This last testament is unexpectedly benign, and even affirmative:

I have been entirely sincere in composing this final work; it will not win me any favor with the critics, although out of posthumous vanity I still hope for that. But it’s of no consequence. As far as I know, this book will be the most accurate description extant of the sixty years of German postwar history; except for those few stories still in print, there is no other history of the period worth speaking of. And I believe it will show that there are good reasons to respect our country—its arrogance and mediocrity notwithstanding.

As M. earlier recalled, “A beggar whom Rudolf had admired once said that confessions are clearest when they are recanted.”

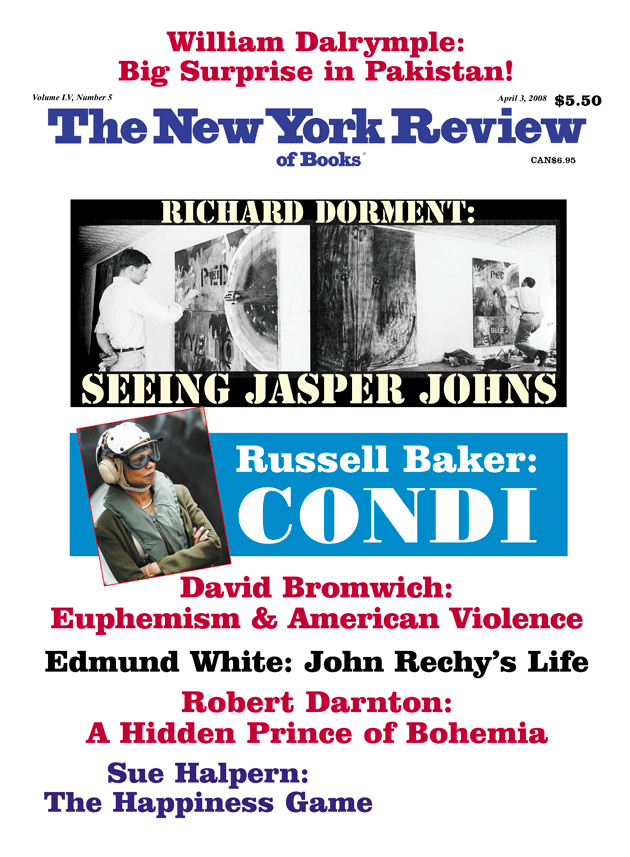

This Issue

April 3, 2008

-

1

The End of the Novel, translated by Ewald Osers (Braziller, 1992). ↩

-

2

This is a nice instance of what might be called auto-intertextuality, for in the opening pages of The End of the Novel the narrator is found researching a poison with which to kill off the leading character in the book that he is writing and that eventually he edits back to nothing—hence the title. The poison he chooses is a preparation from the spurge family of plants with milky juices: it “slowly relaxed the muscles, so that he would feel the pain, that glorious return of nature to the body, on which he had so often discoursed, too often perhaps, eventually leaving him.” ↩