1.

In 1857 Charles Baudelaire dedicated his collection of poems, Les Fleurs du Mal, to his “friend and master” Théophile Gautier. Following a trial for obscenity (guilty on six counts), The Flowers of Evil rightly became the most famous book of erotic poetry published in nineteenth-century France, and the wording of Baudelaire’s dedication to Gautier became equally celebrated: “Au poète impeccable, au parfait magicien ès lettres françaises” (“To the irreproachable poet, perfect magician of French literature”).

The significance of this flamboyant dedication to Gautier, and especially that unexpected word magicien, has puzzled readers ever since. But a forgotten sequence of Gautier’s bizarre short stories, never collected in his own lifetime but now known as Les Contes fantastiques, may throw some light—perhaps a blue, phosphorescent, erotic moonlight—on this intriguing question.

In 1857 Théophile Gautier was forty-six, and at the height of his reputation as a poet and critic. Having started his career as an art student in Paris, he had fallen spectacularly under the influence of Victor Hugo and enlisted as one of the shock troops of Romanticism, sporting shoulder-length hair and scarlet waistcoats, and publishing ultra-Romantic poetry (Albertus, 1832) and a scandalous novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin (1836), whose heroine spends much of her time dressed as a man. Gautier was immediately snapped up by one of the new breed of newspaper magnates, Émile de Girardin (the Rupert Murdoch of his day), put on a large salary, and employed to write a column, or feuilleton, every week for the next thirty years, first on the popular mass-circulation newspaper La Presse and later on the government-sponsored Le Moniteur universel.

The rapid, mandarin brilliance of Gautier’s prose was widely recognized and admired, together with his famous facility. “It’s all a question of good syntax,” he would say. “I throw my sentences into the air…and like cats I know they will always land on their feet.” He was also known for his adventurous travel books (dashed off during summer vacations), his love of Mediterranean cooking, his interest in opium, and his uninhibited love of the female nude (ideally in marble, but if necessary in the bath), as typically appears in his glistening “Le Poème de la Femme” from Émaux et Camées:

…Elle semblait, marbre de chair,

En Vénus Anadyomène

Poser nue au bord de la mer.1

He featured frequently in the humorous cartoons and caricatures of the day, usually bearded and cross-legged in the Oriental manner, and surrounded by amorous cats, entwining hookahs, and plump, faintly suggestive cushions. He was endlessly pictured by the most renowned Parisian photographer of his generation, Félix Nadar (see illustration on page 62), who was fascinated by his large, amiable, crumpled face, once compared to a double bed on a Sunday morning.

The ever-grateful Baudelaire subsequently wrote a long essay on Théophile Gautier in 1859. In this he analyzed the master’s limpid prose style, praised his poetry—now changed into the finely “chiseled” Parnassian style of Émaux et Camées—and acknowledged his huge impact as a drama and art critic. Yet he insisted that the real Gautier was still a virtually unknown writer for the general public—“Gautier inconnu,” as he repeatedly called him.

Some 150 years later, when most of his journalism and travel writing has been long forgotten, and his Parnassian poetry has fallen out of fashion, the same remains true for English-speaking readers, and even more remarkably for the French themselves. It was not until 2002 that any of Gautier’s work was accepted for publication in the Éditions Pléiade, that ritual (almost religious) acceptance into the national literary canon, even though his contemporaries like Hugo, Nerval, Balzac, and Baudelaire himself were all “canonized” in the famous severe green and gold livery of the Pléiade many years ago.

For French university students as well as general readers, the standard judgment of Théophile Gautier has remained the lordly dismissal of the critical panjandrum Émile Faguet, written over a century ago but still quoted in all the textbooks:

Gautier entered into our literature absolutely without having anything to say to us. His intellectual foundations were null and void. He had not a single idea in his head…. He was a second-rate poet, pleasant enough to be sure, but with-out psychological insight, or the least understanding of the human heart.

It was only when I chanced upon some of Gautier’s contes fantastiques, picked up in various battered nineteenth-century paper editions (smelling so oddly of cigar smoke and cinnamon) from the green secondhand book-boxes along the quais in Paris, that I began to wonder about the magicien.

2.

This happy encounter with Théophile Gautier took place over thirty years ago. In 1974, I had gone to live in Paris, just after completing Shelley: The Pursuit. I was aged twenty-nine, living in a fifth-floor attic room near the Gare du Nord on £100 ($150) a month and supporting myself by freelance journalism, most of it published by The Times in London. At least once a fortnight, well after midnight, I used to walk down to the all-night Bureau de Poste near the Bourse, anxiously carrying my new article in a brown manila envelope.

Advertisement

In the cavernous hall of the Bureau, pleasantly perfumed with Gitanes and cow gum and lino polish, I would stick on the big blue Priorité label and gingerly slide the envelope through the grill, surreptitiously watching till the Existentialist night clerk had actually put it in the Special Delivery canvas bag, hung on a brass hook behind his seat. Then our eyes would meet and occasionally I would get a reassuring greeting along the lines of “Ça va, vous, heh?”

Then came the triumphant stride back up the boulevard Magenta and the sharp left turn into the steep, narrow, cobbled, and deserted Marché Cadet (where Gautier’s friend Gérard de Nerval was once arrested for removing his trousers in public), now smelling faintly of crushed peaches. Next a quick lateral diversion past Gautier’s own tall, shadowy house at 14, rue de Navarin (with a salute to his mistress in the house opposite, no. 27), and finally several congratulatory ballons de rouge at a quiet little café I knew near the place Anvers off Pigalle, which always remained open until 4 AM.

I had set myself to research the life of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who was driven mad by an unhappy love affair and committed suicide in 1855, as vividly recounted by Gautier in an obituary for Le Moniteur. In many ways this became an increasingly lonely and terrifying project, as I have recounted in my book Footsteps (1985). Gradually I began to feel closer to Gautier, himself a working journalist and, when he was twenty-five in 1836, just having finished his novel Mademoiselle de Maupin and starting out on his career with the newspaper La Presse.

The shy, elusive Nerval, it seemed to me, was the victim; while the lumbering and genial Gautier was the survivor. He once brilliantly described himself as such, in a mischievous little poem entitled “L’Hippopotame,” which begins:

L’Hippopotame au large ventre

Habite aux Jungles de Java

Où grondent, au fond de chaque antre

Plus de monstres qu’on n’en rêva….2

Slowly it was Gautier who became the benign, reassuring presence in my attic room. As an act of friendship, almost of personal gratitude, I began to translate his strange stories, very few of which (except La Morte amoureuse) had ever appeared in English before. Translating him—with my coffee-stained Petit Robert between us—became very like talking to him. The fact that he cordially disliked England, thought the English deeply uncivilized (“everyone there lives on steamed potatoes”), and once described London in one of his wonderful throwaway phrases as “la ville natale du spleen” seemed more of a refreshment than an insult. (And how could you translate that phrase? “London, the home town of depression” or “London, birthplace of the blues”?) In a certain sense Gautier taught me both the French language and something of the French savoir-vivre; as well as welcoming me with a wink into the salons of the Second Empire.

Thanks also to the forbearance of my landlord, to whom my translations are still dedicated, I survived in Paris for the best part of two years. I went back to London in spring 1976, with the typescript of seven contes fantastiques and twelve multicolored exercise books, ritually purchased month by month from Gibert Jeune at place Saint-Michel and filled with Nerval materials. Besides these, I had copied out three hundred pages of Gautier’s (then) unpublished letters from the Chantilly Archives.

A thirteenth exercise book (deep purple) was filled with Gautier’s suppressed erotic writings, including many poems and the notorious Rabelaisian “Lettre à la Président” (once “published in Belgium” but immediately banned). This was written to his beloved friend and confidante Madame Apollonie Sabatier, about his sexual adventures on his Italian journey in 1850, and forms the secret background to his story “The Tourist” (“Arria Marcella”), about a young man waylaid by a beautiful but voracious woman in the ruins of Pompeii.

I meticulously copied out this salacious “Lettre à la Président” from the manuscript, sitting primly at a high, isolated desk in the restricted section of the Bibliothèque Nationale, known in those days as “L’Enfer” (Hell, or perhaps, the Infernal Regions). It was staffed only by male assistants of a certain age, who were all required to wear (fantastic as this now sounds) scarlet rubber aprons reaching from the chin to well below the knee. I modestly quoted a short passage from the Lettre in my original postscript to My Fantoms when it was first published in 1976. It is not very long or shocking, but caused a certain amount of surprise to readers familiar only with the Parnassian poet.3

Advertisement

All this material was packed into a respectable blue hold-all bought in the Marché aux Puces, and successfully carried through customs at Dover, who merely wondered if I might be importing cannabis in the carrying case of my Olivetti portable. Well, I was certainly carrying Gautier’s delightful story “La Pipe d’Opium” (“The Opium Smoker”), which has a lot to say about intoxication, and a young woman’s ankle coming through the ceiling. My postscript to his stories, originally drafted in my Paris attic in 1976, is retained in the new edition of My Fantoms.4

It was perhaps my attempt at a prose version of Gautier’s poem “Le Château du Souvenir,” his recollections of his first bachelor rooms in Paris, a tiny two-room apartment in a semi-derelict seventeenth-century building overlooking the old Louvre Palace at the impasse du Doyenné. It was here that he was visited by the very first of his fantômes, a sophisticated young lady (in fact a marquise) who steps down from a decorative silken tapestry and advances alarmingly toward his bed, as recounted in “The Adolescent” (“Omphale: Histoire Rococo”).

3.

Strong autobiographical elements run right through all Gautier’s stories. Sainte-Beuve was the first to suggest that his fiction might hide a secret confession, like Musset’s Confession d’un enfant du siècle. Three early stories—“The Adolescent,” “The Priest,” and “The Painter”—evidently reflect Gautier’s bohemian life in the impasse du Doyenné. These years were also described in Nerval’s heartbreaking essay Petits châteaux de Bohème, and much later in Arsène Houssaye’s worldly Confessions (1885).

The later stories arise from Gautier’s work as a journalist and travel writer for La Presse; and especially his journeys to Spain in 1840 and to Italy in 1850. The final story, “The Poet,” was based on his obituary of his old friend Nerval, whose suicide profoundly shook Gautier and brought the bohemian phase of his own life to an end. It was the same year he moved to the government newspaper Le Moniteur universel. All the women in these stories—even Nerval’s imaginary and ultimately lethal muse-figure “Aurélia” (who was the actress Jenny Colon)—have their originals in real life, but are transformed into Gautier’s fictional fantômes.

Though the biographical source of these hauntings was suggested—and partly guessed at—in my original postscript to My Fantoms, I did not then realize how literally they could be traced. All Gautier’s letters and stories have since been published, finally rendering my notebooks redundant (except for the purple one). The letters reveal much more fully than before what an immensely turbulent emotional life Gautier lived until his late forties, an inner life which he had successfully deflected into his poetry and above all his fictions. His Correspondance Générale,5 occupying no less than twelve volumes, is a true labor of love and forensic investigation by his superb, gallant, and (in all the circumstances) forgiving editor, Claudine Lacoste-Veysseyre.

The letters display a tough, professional author who always, touchingly, saw himself as a dreaming poet. A man who worked hard but also played hard in the manner of the times (food, travel, sex); and so was much loved—“le bon Théo“—by an extraordinarily wide circle of gifted male friends: Nerval, Hugo, Dumas, Baudelaire, Flaubert, Delacroix, and Gustave Doré. He appears a cynical but tender and sentimental lover, and perhaps for that reason always immensely attractive to women; and a critic always valiantly prepared to use his journalism to launch a new poet, painter, or actor (or, of course, actress).

There is a whole series of letters to Gautier’s overlapping lovers, several of them known only by their noms d’amour or (when things got rough) their noms de guerre. They include his first teenage affair with a local bookshop owner, Madame Damarin (reputed to have lasted twelve years); the doomed romance with “La Cydalise,” a pale young seamstress with a tiny wasp-waist, who took up permanent residence in the Doyenné, but tragically died there from consumption; a long-lasting liaison with “La Victorine,” a gorgeous but hot-tempered and domineering young widow; Mlle Eugénie Fort, a girl of good family and striking Spanish looks (“when she came to my bedroom she turned it into the Alhambra palace”) who suddenly presented him with an illegitimate son; the actress Alice Ozy, famous for her long legs, with whom Gautier would take baths; and Marie Mattei, a Corsican adventuress who dressed in tight waistcoats and rolled him cigarettes in bed after lovemaking, as recalled in his poem “Une Ange chez Moi.” In 1843, another typical (but unknown) admirer wrote to him on publication of his Spanish travel book: “How I love your long deep velvet glances, oh my Spaniard!”

From the start, Gautier was leading a double life. He was an immensely hard-working writer by day, who was already proclaiming the purity of Art for Art’s sake in 1832 (“As a general rule, when something becomes useful, it ceases to be beautiful,” Preface to Albertus). But by night he was a gallant, a charming but opportunist adventurer, almost of the Byronic type. This double existence is brilliantly described in perhaps the most original of Gautier’s early stories, “The Priest” (“La Morte amoureuse”). It was written for Balzac’s monthly magazine, La Chronique de Paris, in 1836.

Here a young priest, fresh from the seminary, is pursued by a worldly and sensual female vampire. But conventional (“bourgeois”) moral values are stood on their head. The beautiful vampire Clarimonde shows herself to be a truly generous and protective spirit, almost angelic; while the priest’s saintly spiritual adviser, the solemn, glowering Father Serapion, is slowly revealed to be a cruel and possibly demonic figure, intent on the destruction of all human happiness. The idea of necrophilia, also deliberately and provokingly introduced by Gautier, is subtly disarmed and turned into what is probably an elegy for the consumptive seamstress La Cydalise.

This masterly story of mirror images and moral reversals provides a mocking but curiously accurate self-portrait of Gautier’s own double life in these years. Clarimonde (despite her early resemblance to La Cydalise) soon becomes largely a portrait of La Victorine, whose violence and sensuality dominated Gautier for nearly a decade. They set up house together in the rue Navarin, and when their fights became too violent, Gautier took rooms on the opposite side of the street. There is a letter from Balzac inviting them both to supper at Passy in 1836, and another from Arsène Houssaye, volunteering to prevent them from “tearing each other’s hair out” after a supper party in 1837. Gautier described Clarimonde/Victorine years later in his poem “Le Château du Souvenir”:

Sa bouche humide et sensuelle

Semble rouge du sang des coeurs,

Et, plein de volupté cruelle,

Ses yeux ont des défis vainqueurs….6

Houssaye conjured a suitably melodramatic picture of her in his Confessions:

A beautiful girl with dark brown hair, a big scarlet mouth, and hell-fire eyes…she was the woman whom we all simply called “la Victorine,” and who pounced on Théo like some lioness, and subdued him with her great mane of hair and her terrible claws.

(Perhaps it is not surprising that Houssaye later became director of the Comédie-Française.)

This kind of haunted, doubled, or divided love life continued right to the end of Gautier’s career. The tantalizing picture The Two Sisters, painted by Théodore Chassériau in 1843 and reproduced on page 60, expresses a profound truth about Gautier’s schizophrenic desires, his mirror-image romances, and his looking-glass longings. A distinguished man of letters in his fifties, living an apparently solid bourgeois life in a charming house in the leafy suburbs of Neuilly, at 32, rue de Longchamps (which still exists, a ten-minute métro ride from the Étoile), his heart was still utterly divided between two women.

They were the two famous Grisi sisters: Italians, artistically gifted, and astonishingly beautiful. One was an opera singer, the other a ballet dancer. Ernesta Grisi was stormy and passionate, and Carlotta Grisi was tranquil and utterly dedicated to her art. Ernesta lived under his roof at Neuilly and bore Gautier two daughters, while organizing his domestic life, singing under the trees in his garden, and cooking him risottos. Carlotta danced in all the capitals of Europe, exchanged love letters with Gautier for thirty years, and only once kissed him on the lips. All this, one may say, was predicted in My Fantoms.

4.

The French Enlightenment had always encouraged erotic writing, of the kind found in Voltaire, Diderot, and Laclos (Les Liaisons dangereuses). It was looked on as an elegant proof of sophisticated manners and civilized values. Sex, after all, was a form of witty conversation. But ghost-story writing, by contrast, had been seen as essentially vulgar and childish: a strange, alien northern tradition belonging to the barbarous English like “Monk” Lewis, or the unhinged Germans like the Brothers Grimm or E.T.A. Hoffmann. It was regarded as the unfortunate product of bad lighting, long winters, and Protestantism.

The defeat of Napoleon and the arrival of Romanticism in France changed all that. When Shakespeare was brought to the Odéon theater in 1827, it was Hamlet, Prince of Denmark that took Parisian audiences by storm, opening with the memorable ghost scenes on the battlements of Elsinore. The new postwar generation of bohemian Romantics, bored with French classicism, proclaimed the genius of Shakespeare, Byron, Walter Scott, Goethe, and Hoffmann—all writers who used ghosts, demons, and hauntings in their work. (Byron was wrongly credited with Dr. Polidori’s The Vampire.) Nerval’s translation of Faust, published in 1828, with its ghostly scenes on the Brocken mountain, suddenly brought him fame when he was only twenty. Hoffmann’s sinister The Sandman (1816) became a best seller, and his Tales were so popular that they were eventually the source for an opera by Jacques Offenbach.

Charles Nodier, friend of Hugo and the fashionable director of the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal in Paris, began translating Hoffmann into French in the 1820s and started to publish his own strange ghost stories with titles such as Smarra, ou les démons de la nuit (1821). His most outlandish fiction, Histoire du Roi de Bohème et ses sept châteaux (1830), was the most influential of these, and its title became a sort of watchword for both Gautier and Nerval. Nerval was always announcing which of Nodier’s seven mystical châteaux he had currently arrived at in his increasingly disturbed and peripatetic life.

Gautier published a brilliantly funny and perceptive essay on the vogue for Hoffmann, contrasting the naive devils of Germany with the super-sophisticated devils of Paris, in the August 1836 edition of the Chronique de Paris. He took over the cult of Hoffmann in his own early story “Onuphrius Wphly” (“The Painter”), which was teasingly subtitled “The fantastical vexations of a Hoffmann admirer.” Onuphrius (Gautier himself as an art student) is put through every Hoffmannesque torture, including being buried alive in a coffin, and having the top of his skull sliced open “like a pie crust,” and finding all his ideas bursting out into the room “like budgerigars fluttering from an open birdcage door,” while the devil (naturally) steals his very beautiful mistress.

But Gautier soon achieved something much more daring by combining the German ghost story with the French erotic tale. He can claim to have created, in Clarimonde, one of the earliest female vampires: a distinguished line that stretches right down to the engaging, slinky cartoon-character Vampirella (created in 1969); and in the story of Arria Marcella in “The Tourist” to have released a whole generation of beautiful and concupiscent corpses, mummies, revenants, dolls, femmes mécaniques, and libidinous statues. It was a tradition that quickly took root in nineteenth-century France, already blossoming in Prosper Mérimée’s masterpiece La Vénus d’Ille (1837), in which a vast, gleaming Roman bronze Aphrodite climbs off her plinth and slips into bed with her trembling human bridegroom.

In fact Gautier never provided a collective title for his stories, and in France they are known generically as his Contes fantastiques.7 Yet in them he repeatedly used the collective term fantômes, to mean specifically female spirits. His fantômes are all seductresses, ravishing mischief-makers, softhearted vampires, generous courtesans, fatal temptresses, or simply ardent thousand-year-old muses. What they have in common is that all of them come back from the dead, seeking human lovers. Indeed the contemporary cinema word undead might be used now. One can imagine a Grand Guignol title like Those Undead Dolls. But in the end I invented the decorous, slightly arch word Fantoms for the title.

5.

Gautier’s female spirits are of very varied kinds and intentions, though they are nearly always dazzlingly beautiful. This also poses delicate problems of rendering Gautier’s precise, highly pictorial, and suggestive prose. His original training as an art student always shows in the slightly heightened visual emphasis of his descriptive writing. But the gross, lubricious cartoons of the “Lettre à la Présidente” are transformed in the Fantoms into a quite different kind of eroticism. Here, for example, the tourist Octavian first lays eyes on the antique beauty Arria Marcella, come back to life after being buried in the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius at Pompeii nearly two thousand years before:

Something like a powerful, electrical shock passed through his heart, and as the woman turned to look at him, he had the sensation that his chest released a shower of crackling sparks…. Her mouth was curled at the corners with a hint of mockery, and the smoldering energy of those inflamed and scarlet lips seemed to cry out against the calm, mask-like pallor of the face…. Her arms were naked to the shoulder, her nipples pressed up against the dark pink material of her tunic, and her proud breasts beneath descended in two curves that could have been cut in marble by Phidias or Cleomen.

Nor was Gautier content to present Arria as some lascivious, animated mummy. She falls genuinely and passionately in love with Octavian, and through her desperation to escape from death, Gautier achieves one of the great declarations of his fiction:

“No one is truly dead until they are no longer loved….” The concept of the conjuration of love, which the young woman expressed in this way, entered into Octavian’s system of philosophy. It is a system that I am much inclined to share with him….

Nothing, in fact, actually dies: everything goes on existing, always. No power on earth can obliterate that which has once had being. Every act, every word, every form, every thought, falls into the universal ocean of things, and produces a ripple on its surface that goes on enlarging beyond the furthest bounds of eternity.

This indeed is one of Gautier’s most haunting and seductive ideas, which drives and animates (in its fullest sense) each of the seven stories that I eventually collected in My Fantoms. It is the credo of a brilliant but troubled and disillusioned Romantic, who still hoped against hope for the return of some kind of unearthly ecstasy and transcendence. An old soixante-huitard before his time, perhaps?

Yet Gautier was always haunted by material and earthbound limitations: of his own heavy and demanding body, of his increasingly domesticated career, and of his endless, treadmill newspaper-writing. One remarkable solution was to create that most airborne of fantôme forms—a ballet. On his return from Spain in the spring of 1841, where he had first observed fierce young Andalusian women dancing the flamenco—their rhythms wonderfully caught in his poem “Carmen”8—he suddenly saw the twenty-year-old Carlotta Grisi dancing on stage at the Opéra. It was a coup de foudre, and he immediately decided to create a ballet for her. Within three days he had written the book of the most successful Romantic ballet in the whole nineteenth-century repertoire: Giselle.

Giselle is based on the old German legend of Les Willis, the beautiful diabolic dancers of the Teutonic greenwood, as recounted in a poem by Heinrich Heine. Gautier’s adaptation of the legend for Giselle is simply one of My Fantoms transformed into dance. Act 1, set in daylight, recounts the tale of the beautiful young peasant girl who is betrayed by her aristocratic lover and tragically dies in the forest (perhaps by dancing herself to death). In Act 2, a nighttime drama, the undead Giselle joins the fatal band of the Willis, intent on their murderous revels, but finally intervenes to save her lover from the inevitable, lethal enchantment. The whole trajectory of the story is pure Gautier, a story of agonized love from beyond the grave. The ballet has been brilliantly produced for over 150 years, and its various roles danced by Petipa and Grisi, Nijinsky and Karsavina, Dolin and Markova, Nureyev and Fonteyn. But Gautier’s “book” is almost entirely forgotten.

Here is the opening of the second of the two acts, as I copied it down long ago in my Parisian attic, from the original yellowing livret of 1841. It is my final translator’s salute to “a friend and master…and magicien“:

The theater reveals a forest on the edge of a lake…. The bluish light of an unnaturally bright moon floods the scene with a chill, misty luminescence…. Somewhere in the distance midnight strikes…. Hilarion and his friends listen to the clock with growing terror. Trembling they look about them, waiting for the apparition of those lovely, light foot fantoms. “Quick, let’s slip away,” whispers Hilarion, “the beautiful Willis are pitiless, they seize hold of travelers and force them to dance, on and on and on, until they drop dead with exhaustion or are swallowed up in the icy waters of the lake.” But already a strange and unearthly music is filling the theater….

…And filling the pages of My Fantoms, I hope.

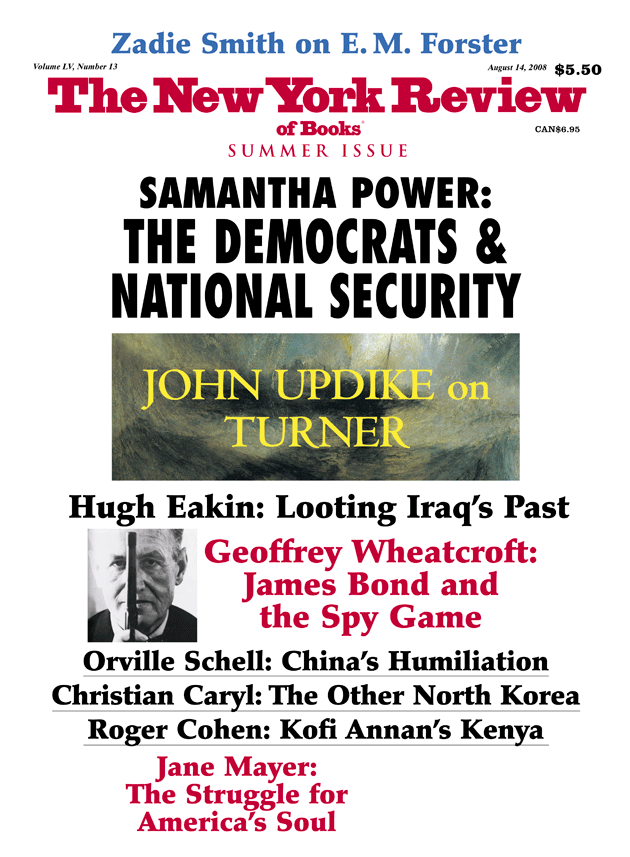

This Issue

August 14, 2008

The Devastation of Iraq’s Past

Burdock

E.M. Forster, Middle Manager

-

1

“She seemed like a Venus Anodyomene, posed naked by the sea, her flesh all marble,” from Enamels and Cameos (1852). ↩

-

2

“The big-bellied hippo dwells in the jungles of Java, where more monsters than you have ever dreamed of growl from the depth of every den around him….” ↩

-

3

For example, one episode begins: “The other evening Louis and I were unexpectedly visited by a young Venetian beauty, who having completed a number of preliminaries to satisfy herself that we were not police-informers, lifted up her dress and unhooped her corset to allow us to run our eyes over her naked charms. Her breasts proceeded to explode into the room, crashed straight through the floor, burst out into the via Condotti, and shuddered down the Corso as far as the Piazza Venezia, leaving us buried in a deluge of ‘lilies and roses’ (Dupaty style!)….” ↩

-

4

This essay will appear in somewhat different form as the introduction to the new edition of My Fantoms, to be published by New York Review Books in August. ↩

-

5

Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1985–2000. ↩

-

6

“Her moist and sensual mouth seems red with the blood of human hearts, while her eyes flash savage provocations, and brim with cruel delight….” ↩

-

7

Various different selections have now appeared under this title in France, published by Gallimard Folio (1981), Flammarion (1981), Livre de Poche (1988), and Hachette (1992), and finally subsumed into La Plé-iade (2002)—which, astonishingly, still does not publish a single one of his poems. Evidently the magicien has triumphed over the poète impeccable in popular esteem, which would have brought an ironic smile to Baudelaire’s lips. ↩

-

8

“Carmen est maigre,—un trait de bistre/Cerne son oeil de gitana./Ses cheveux sont d’un noir sinistre,/Sa peau, le diable la tanna….” (“Carmen is very thin/Her gypsy eye is circled with a sepia line./Her hair is menacingly black,/The devil himself has suntanned her skin….”) ↩