The situations are superficially the same—presidential candidates trying to remove an obstacle to their election arising from their church membership. But the obstacles are quite different. The objections some have to Mitt Romney’s religion are twofold, theological and cultural. Those against John F. Kennedy when he gave his 1960 speech in Houston about his Catholicism were more solidly political. The theological problems with Romney come from evangelicals, who know that his Jesus is not a member of the divine Trinity. Romney has assured them in his speech on religious liberty, also given in Texas, in early December, “I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and the Savior of mankind.” That may not be enough for those insisting on their own orthodoxy, since Brigham Young wrote that “intelligent beings are organized to become Gods, even the Sons of God,” and that these divinized believers may be the saviors of the worlds they dispose of. But Romney is right in claiming that such points of theology are irrelevant to the practical morality involved in politics. “Sons of God” is not a political slogan.

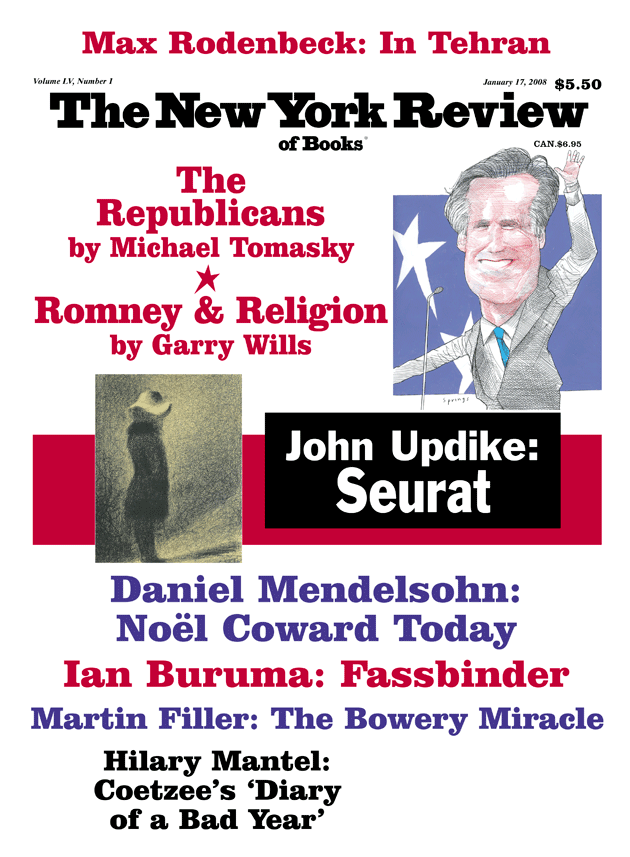

But theology is not what bothers most of those who feel uneasy about Mormonism. They object to its unfamiliarity. Mormons are a small minority in the country (1.3 percent), with what seem to be odd ideas and practices. There are only fifteen Mormons in Congress, far fewer than women or blacks. Of these, five come from Utah and none from east of the Mississippi. In most of the country, few people think they know any Mormons. People are not comfortable with what they feel they do not know about or understand. To fight this “weirdo factor,” Romney stresses his mainstream appearance and conduct. With a hit at Rudolph Giuliani’s multiple marriages and estranged children, he has offered his own family as a symbol of the values his faith upholds: “You can witness them in Ann and my marriage and in our family.”

The only objection to Mormons on political grounds would be their record of polygamy and racism, both of which have been officially abjured. But Kennedy’s problem was precisely political. Catholics were familiar enough to Americans—there was no weirdo factor. (People wearing white hoods over their heads had little right to call others weird.) And Kennedy’s opponents were not interested in theological questions like transubstantiation. But there were solid grounds for political doubts about Catholics. The Vatican had not, in 1960, formally renounced its condemnation of American pluralism and democracy. In fact, one of Kennedy’s advisers on his Houston speech, the Jesuit John Courtney Murray, had recently been silenced by the Vatican for defending religious pluralism.

There was a cogently argued case against papal politics. Paul Blanshard had maintained, in the best-selling American Freedom and Catholic Power (1948), that Catholics were just pretending to be democrats till they could get into power and imitate such Vatican-approved regimes as that of Francisco Franco in Spain. A strong lobby, Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State, had continued to argue the Blanshard position. It had successfully blocked the sending of a full ambassador to the Vatican. The Protestant ministers who organized against Kennedy’s campaign, under Norman Vincent Peale, feared the Pope’s power more than his doctrines—just as they had when Al Smith ran for president in 1928.

Kennedy could not openly do what the Catholic historian Lord Acton did when Pius IX attacked democracy. Acton told Gladstone that he did not know half the papal atrocities, but these did not matter, since British Catholics paid no attention to them. But Kennedy sidled up to such a statement. Not only had he, too, opposed the Vatican ambassador and financial aid to Catholic schools; he also declared that “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute.” This went beyond what Father Murray was advocating. It was as open an attack on Spanish “integralism” as anyone could wish. Kennedy said he would follow his own conscience, not allowing any church interferences with what his conscience dictated: “I believe in a President whose religious views are his own private affair.” In his speech, he faced squarely points on which the Vatican might like to interfere:

Whatever issue may come before me as President, if I should be elected—on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling or any other subject—I will make my decision…in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressures or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.

If his conscience and his public duty were ever in conflict—which he thought impossible—he said, “I would resign the office.”

Kennedy had to convince people that he would not let the Vatican push him around. Romney has let evangelicals know that he would let them push him around. He not only has given them a theological formula on Jesus which he hopes they will accept—he implicitly has attacked Kennedy’s absolute separation of church and state using the evangelicals’ own slogan: those who think (like Kennedy) that “religion is seen merely as a private affair” are, Romney said, “intent on establishing a new religion in America—the religion of secularism. They are wrong.” That phrase has not been much noticed in public comments on Romney’s speech, but it is a key statement for the evangelicals. Like George Bush’s speechwriters, Romney has learned the code of Rightspeak—just as he learned Leftspeak when running for governor in Massachusetts.

Advertisement

That secularism is a religion is a position fiercely held by some on the right. They use it to say that separating church and state breaches the First Amendment, which forbids the establishment of a religion. In their topsy-turvy arguments, the First Amendment thus forbids the separation of church and state. Romney was speaking in that code. In his speech he made many other appeals to the religious right, as when he put “the breakdown of the family” in his list of most pressing national problems (another hit at Giuliani). He praised the use of religious symbols “in our public places.” Though he did not specifically mention the Ten Commandments in courtrooms, he implied approval of their presence there. (He should be questioned on this matter.) The Bush administration and its lackeying Republican Congress would do anything for the religious right. When the right said “Jump!” on the Terri Schiavo case, the President and Congress said “How high?” Romney signals that he would act in the same way.

Like Kennedy, Romney is not very strong on his use of history. In their Texas speeches, they both invoked the myth of Pilgrims and Puritans coming to America for religious freedom. Kennedy said that “our forefathers died… when they fled here to escape religious test oaths.” Actually, there were religious test oaths in most colonies, and Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony punished heresy with exile, the stocks, lashes, tongue-boring, and ear-cropping. After the colony hanged its sixth Quaker, King Charles II ordered it to stop killing his subjects for their religious views—reversing the mythology of our grade schools. Romney is closer to the truth when he says:

Our nation’s forebears…came here from England to seek freedom of religion [not true]. But upon finding it for themselves, they at first denied it to others [true].

He then cleverly compares Brigham Young’s travails to the exiling of Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams, making Mormons that paradoxical thing, very American heretics.

Kennedy was stronger, though, on the constitutional period, tying it to the Founders’ Deism and Jefferson’s Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. The Constitution never mentions God, but Romney has tried to sneak Him in when making this historically indefensible claim:

Freedom requires religion just as religion requires freedom…. Freedom and religion endure together, or perish alone.

He thus failed to state a fundamental democratic premise: that religious freedom should by definition include the freedom not to believe in a religion.

Kennedy said that the democratic values of America are “the kind I fought for in the South Pacific, and the kind my brother died for in Europe.” Romney and his strapping sons never wore the uniform—they think running for president is their way of waging a war they support in Iraq. But Romney invoked the war service of George H.W. Bush, who introduced him in Texas. It was heroism by proxy.

Has Romney been able to “do a Kennedy,” as his speech was billed in the press? Far from it. Kennedy was on the side of the future. He defied the Vatican’s ban on American-style democracy, which was rescinded in the Second Vatican Council, convened after his election. Romney—looking to the past, and specifically to the current Bush administration’s position—kowtowed to the religious right. Saying that he opposes religious tests, he passed that one.

—December 19, 2007

This Issue

January 17, 2008