Marguerite Duras was a huge presence in the 1980s and early 1990s when I lived in Paris. She was very old—in her seventies—and very alcoholic, and her disintoxication cure in late 1982 at the American Hospital was much written about (not only by journalists—she wrote about it, and her companion Yann Andréa did as well in a book called M.D.). Just when people thought her liver or her kidneys would give out, she rose from her ashes and wrote The Lover (1984), a story drawn from her youth in Indochina that sold a million copies in forty-three languages and became the inspiration for a major commercial movie.

Before her cure, she was holed up in her château dictating one much-worked-on line a day to Andréa, who would type it up. Then they would start uncorking cheap Bordeaux and she’d drink two glasses, vomit, then continue on till she’d drunk as many as nine liters and would pass out. She could no longer walk, or scarcely. She said she drank because she knew God did not exist. Her very sympathetic doctor would visit her almost daily and offer to take her to the hospital, but only if she wanted to live. She seemed undecided for a long time but at last she opted for life since she was determined to finish a book that she’d already started and was very keen about.

There was always something preposterous about her. When she was feeling well enough she surrounded herself with courtiers, laughed very loudly, told jokes, and had opinions about everything. She was an egomaniac and talked about herself constantly. Almost three years after her cure she created a scandal by speculating recklessly about the most famous (and still unsolved) murder case in recent French history—the case of Little Grégory. This child, Grégory Villemin, had been killed and trussed and dumped into a culvert. He was just four and a half years old. More than a hundred journalists were hovering around the site of the murder, the village of Lépanges near Épinal in the Vosges.

And then on July 17, 1985 (273 days after the murder), Marguerite Duras (once again drinking heavily) visited the town briefly, studied the house where Little Grégory had lived, and published a front-page article in Libération announcing to the world that she knew who had done it: the mother, Christine Villemin! Duras’s main evidence was that there was no garden around the little house. This proved that Christine was unhappy, that her husband was forcing sex on her, that she was just staring into space all day and sitting about without any occupation at home, dreaming up atrocious crimes. It was a modern tragedy, Duras claimed, in the tradition of Racine. Even though the mother, who had at first been arrested, had been freed because of the lack of evidence and had specifically refused to speak to her, Duras had no doubts that Christine had done it. She was careful to point out that she didn’t judge the young woman. Any woman was capable of this sort of violence, Duras assured her readers, especially if she was being subjected by her husband to bad sex.

Serge July, the editor of Libération, was so embarrassed by Duras’s article that he printed a less heated version of the events beside it—a virtual disavowal that she considered an unforgivable betrayal. Hundreds of readers wrote in, most of them disapproving of Duras’s article. Many prominent women, including Simone de Beauvoir and Simone Signoret, attacked the article. Duras never looked back or admitted she’d been intemperate. The title of the article had been “Christine Villemin, Sublime, Necessarily Sublime.” Duras said that she was sure that Christine “had killed perhaps without knowing it just as I have written without knowing it.” (Since Duras drank in order to write she seldom recognized her own writings when she reread them.)

Immediately afterward (between July 1985 and April 1986) Duras and François Mitterrand (then president) granted several long interviews to the magazine L’Autre Journal, discussing among other things their role in the Resistance. (These interviews were later turned into a hit play, Marguerite and the President.) Mitterrand, after working for the Vichy government, had indeed been a cell leader of the Resistance under the name François Morland; he had organized Frenchmen who had been captured before France’s surrender and held as prisoners of war by the Germans and later released (Mitterrand himself escaped his German prison). And Duras had indeed used her apartment on the rue St.-Benoit (around the corner from the Café de Flore) as a meeting place for resistants, and after the liberation by the Allies she’d edited a newspaper, Libres, reporting on the whereabouts of French men, women, and children coming back from the camps.

Advertisement

Her husband, Robert Anthelme, had been arrested for his Resistance activities and sent to a concentration camp, Bergen-Belsen. When he was liberated a year later, he could barely walk. As Duras writes in one of the rough drafts reprinted in Wartime Writings:

When he weighed his eighty-four pounds and I used to take him in my arms and help him pee and go caca, when he had a fever of 105.8, and down at his coccyx his backbone was showing, and when day and night, there were six of us waiting for a sign of hope, he had no idea what was going on.

What is being reprinted in paperback as The War: A Memoir is called in French La Douleur (Suffering). It is a terse, action-packed, nonfiction notebook hastily scrawled during the war, with no regard to prose style, and published by Duras only in 1985. The notes provide a blow-by-blow account of her fears for her husband’s survival, his long convalescence, and her alternating moods of joy and panic. This text fills seventy pages. It is followed by other accounts of Duras’s war, including a fairly preposterous one (“Albert of the Capitals”) in which she claims that she tortured a French collaborator right after the Liberation. Duras’s biographer, Jean Vallier, denies that she ever acted in this way. She wasn’t a torturer at the interrogation center, Vallier writes, but a canteen waitress (une popotière), which in French doesn’t sound very warlike.

In their interviews with L’Autre Journal neither Mitterrand nor Duras mentioned their activities earlier in the war. The young Mitterrand had served the Vichy government as a clerk concerned with French prisoners of war and had received a medal—the Francisque—for his activities from Pétain. But by 1942 he was already using his contacts with former POWs to start an underground alliance against the Germans. After he was elected president in 1981, however, he would never explicitly condemn the Vichy government and he had dinner in the Élysée Palace with René Bousquet, an old friend and ally in the Socialist Party who had, not incidentally, ordered the arrest of Jewish children in Paris and their transportation to the death camps (thereby exceeding the demands of the Nazis themselves). Bousquet was welcomed by Mitterrand as a frequent guest until 1986, when a public outcry made their friendship difficult to maintain. Nevertheless, the French government under Mitterrand dragged its feet in prosecuting Bousquet, who was finally shot by a madman in 1993—fortunately for everyone, especially Mitterrand.

Duras never mentioned that she, too, had worked as a minor bureaucrat under the Occupation. When she was a young and aspiring but unpublished author, she accepted a position with the government organization that decided on a book-by-book basis whether a publisher would be given paper with which to produce a given title. Essentially, the service of “paper control” for which she worked from July 1942 to the end of 1944 was acting as a state censor. D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was withdrawn, as were titles by Freud, Zola, and Colette. Quantities of paper, however, were allotted to the publication of Goebbels’s memoirs, Paul Claudel’s Ode to Marshall Pétain, and the vilest anti-Semitic garbage of the period, The Ruins by Lucien Rebatet, who, as Jean Vallier writes, had “a sewer mouth that all by itself was able to dishonor an entire epoch.”

It was perhaps because Duras held this sensitive position that her own first novel, Les Impudents (which had been turned down by several publishers), was now accepted and received a glowing review from the brilliant collaborationist critic Ramon Fernandez (who also worked for the paper control service and whose wife Betty was Duras’s best friend). Duras at least was able to admit it years later:

If my first novel finally appeared …it was because I was part of a paper commission (it was during the war). It was bad….

To be sure, everyone not independently wealthy had to have a job, but her position as censor for the Nazi occupiers was certainly one that Duras was eager to forget. Nor did she want to remember that before the war she had worked in the publicity department representing France’s colony in Indochina during the late 1930s, especially at the 1937 International Exposition, the last great manifestation of French colonialism. Most of the French did not object to France having colonies at the time. But Duras, with her considerable powers to mythologize the past, knew how to invent a suitably leftist record for herself.

And she could see her present in a similarly self-serving way. She loved herself, she quoted herself, she took a childlike delight in reading her own work and seeing her old films, all of which she declared magnificent. When toward the end of her life she ran into Mitterrand in a fish restaurant, she asked him how she had become better known to people around the world than he was. Very politely he assured her he’d never doubted for a moment that her fame would someday eclipse his.

Advertisement

It’s easy enough to make fun of her narcissism and her prevarications. But her work was fueled by her obsessive interest in her own story and her knack for improving on the facts with every new version of the same event. For instance, in Wartime Writings there are some previously unpublished pages (about fifty) that are among the most arresting she ever wrote. Written by hand in a notebook during the war, these pages recall her growing up in Indochina and give the first version of the “affair” with the man who would eventually become “the Lover.” There are also fragments that Duras later assembled into her first successful novel, The Sea Wall (1950), which is based on her childhood in Indochina as well.

In her notebook (which was published in French only two years ago) Duras writes in an aside to herself:

It was barely thirteen years ago that these things happened and that our family broke up, except for my younger brother who never left my mother and who died last year in Indochina. Barely thirteen years. No other reason impels me to write of these memories, except that instinct to unearth. It’s very simple. If I do not write them down, I will gradually forget them. That thought terrifies me.

In this first version of the story, there is as in later versions the initial meeting with the Chinese lover on the ferry from Sadec to Saigon. But in this version, in which he’s called Léo, he’s ugly, pockmarked, humble, awkward. After two years of his pleading, Marguerite goes to bed with him just once —and she finds him repulsive. Léo invites Marguerite and her mother and two brothers to expensive Chinese restaurants. The brothers barely speak to him, since he is “beneath” them as a Chinese. The mother counsels little Marguerite to get as much money out of him as possible but never to sleep with him. Marguerite herself has contempt for him:

Léo was perfectly laughable and that pained me deeply. He looked ridiculous because he was so short and thin and had droopy shoulders. Plus he thought so much of himself. In a car he was presentable because one couldn’t see his height, only his head, which, albeit ugly, did possess a certain distinction. Not once did I agree to walk a hundred yards with him in a street. If a person’s capacity for shame could be exhausted, I would have exhausted mine with Léo.

Duras’s parents were both teachers in Indochina, employees of the French government. Marguerite was born near Saigon in 1914. She had two older brothers. Her father, sent back to France on sick leave, died there in 1921. After a few years spent with her mother’s relatives in the north of France, the family returned to Indochina. Her mother bought a farm near the Gulf of Siam and attempted to build a sea wall against the Pacific. But the wall was destroyed by crabs and the rice fields were inundated and ruined. The collapse of the family fortunes was a theme that Duras would return to again and again.

After the rice fields were flooded and the farm abandoned, the family retreated to a small house where her mother would beat her, and, Marguerite writes, her older brother soon picked up the mother’s “habit”:

The only question became who would hit me first. When he didn’t like the way Mama was beating me, he’d tell her, “Wait,” and take over. But soon she’d be sorry, because each time she thought I’d be killed on the spot. She’d let out ghastly shrieks but my brother had trouble stopping himself.

In the notes, we see a family living in poverty, the mother encouraging her daughter to soak her Chinese suitor for money; she was after all conferring a favor on him even to let him spend time with them, since they were, as whites, innately superior. Racism, colonialism, family sadism, extreme poverty, greed—the gritty life of this young woman is quite different from that of the androgynous seductress she becomes in The Lover. In this first version she recalls that she was so badly dressed (in a man’s hat and gold lamé shoes) that she was almost ridiculous. Léo has to spend a month to convince her that her felt hat is in bad taste and doesn’t suit her, so entirely sure is she that her mother (who gave her the thrift-shop hat) knows everything about fashion.

In the first fictional and published version of this story, The Sea Wall (in French Un Barrage contre le Pacifique), the Lover is called Monsieur Jo. He isn’t handsome but he is rich enough to have an elegant car and a big diamond ring. Otherwise, there is nothing desirable about him; the girl’s brother dismisses him as a monkey. In The Sea Wall, the diamond is very generally described as enormous, magnificent, royal. But by the time Duras has progressed to the very last incarnation of the story, The North China Lover (1992), the ring has acquired a history —now the Chinese says:

It could be worth tens of thousands of piastres. All I know is, the diamond was my mother’s. It was part of her dowry. My father had it set for me by a famous Paris jeweler after her death. The jeweler, he came to Manchuria to pick up the diamond. And he came back to Manchuria to deliver the ring.

Most important, the Chinese character in both The Lover and the later book, The North China Lover, is handsome—a proper romantic hero. The story is no longer one about family abuse and greed, about a desperate mother who exploits her virginal daughter. Now it’s become a love story between a European Lolita and a Chinese Humbert, except in this case “the child” (unlike Lolita) is excited by her older lover. Her painful deflowering is carefully recounted, as are the many nights of ecstatic pleasure that follow.

Duras’s editor, Jérôme Lindon at Éditions de Minuit, thought that, after the worldwide success of The Lover, she was making a mistake to follow it up with another version of the same story. Marguerite was outraged at this hesitation on her editor’s part. She switched to Gallimard and brought out the book—again to great success.

The North China Lover bears obvious traces of having started out life as a screenplay. In fact, Duras had been unhappy with the screenplay proposed (and eventually used) to make the film version of The Lover. She had her own ideas. After all, she was a distinguished filmmaker in her own right and had created two (strange, static) masterpieces, The Truck and India Song, as well as many lesser but no less experimental movies. What’s remarkable about Duras’s entire long career is how often she switched from a novel version of a story to the movie version and then to a play, or moved in a different order among the three modes, or modified the story or bits of it from novel to novel, play to play, film to film.

In The North China Lover Duras has combined the movie and the novel forms, while referring explicitly to the preceding novel, The Lover. She writes (referring to herself as “the child”):

The man who gets out of the black limousine is other than the one in the book, but still Manchurian. He is a little different from the one in the book: he’s a little more solid than the other, less frightened than the other, bolder. He is better-looking, more robust. He is more “cinematic” than the one in the book. And he’s also less timid facing the child.

Her prose, always incantatory, has now become the scenarist’s shorthand:

Him, he’s Chinese. A tall Chinese. He has the white skin of the North Chinese. He is very elegant. He has on the raw silk suit and mahogany-colored English shoes young Saigon bankers wear.

He looks at her.

They look at each other. Smile at each other. He comes over.

In the earlier versions of the “affair” (The Sea Wall and The Lover), the figure of the Lover himself was left vague (perhaps because these versions were based on fairly cloudy memories). Now that in old age Duras has succumbed to a “cinematic” form of wish-fulfillment and given up the shadowy, unflattering reality, the Lover has become distinct, tall, good-looking—and the affair itself has taken on weight and body.

Perhaps most novels are an adjudication between the rival claims of daydreaming and memory, of wish-fulfillment and the repetition compulsion, Freud’s term for the seemingly inexplicable reenactment of painful real-life experiences (he argued that we repeat them in order to gain mastery over them). And as with music, the more familiar the melody, the more elegant and palpably ingenious can be the variations.

Duras certainly loved to return to the same handful of themes again and again. For instance, she invented the character of a French vice-consul (based on a Jewish fellow student she’d encountered in Paris during her university years and who became her lover—or so she claimed). This man, in real life called Frédéric Max, was supposedly the original of the disgraced French bureaucrat in The Vice-Consul (1965) who has been transferred from Bombay to Lahore. There in the book he falls in love with a married Frenchwoman, the curiously named Anne-Marie Stretter. The story is retold in the 1972 play India Song (published in 1973), which Duras directed as a film by the same name in 1975 with a cast including Michael Lonsdale, Matthieu Carrière, and Delphine Seyrig, the star of the earlier, equally stylish, and static Last Year at Marienbad (with a script by Alain Robbe-Grillet). That film had been directed by Alain Resnais, who in 1959 had directed Duras’s remarkable script Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Other events and encounters got recycled in a similar way. For instance, Duras met the much younger (and gay) Yann Andréa (she gave him the euphonious last name) in 1980, fell in love with him, and kept writing again and again about their spiritual closeness and physical frustration until her death in 1996. Her “Yann” books include L’Homme atlantique, La Maladie de la mort (a frightful attack on homosexuality), Les Yeux bleus, cheveux noirs (a truce with her beloved’s homosexuality), La Pute de la côte normande, and Yann Andréa Steiner.

I suppose an entire dissertation could be written about this theme of the older woman artist and her gay sidekick or “walker.” I’m thinking of Marguerite Yourcenar and the young gay man she wanted to inherit her fortune, though he surprised her by dying (of AIDS) before her. Or Germaine Greer and David Plante. I’m reminded of the elderly French widow who said to one of my bitchy friends, “I don’t really like homosexuals,” to which he replied, “That’s a pity, Madam, since they are your future” (“Dommage, Madame, c’est votre avenir“).

In Duras’s case, Yann Andréa was by her bedside taking down her last sporadic ravings, which he published in 1995 as C’est tout—a fairly dubious or at least controversial move, a bit like the promotion of de Kooning’s Alzheimer paintings. Certainly Duras while she was still in her right mind wrote some beautiful pages about Yann, especially in the little book Yann Andréa Steiner.

Preposterous, self-obsessed, eloquent, unstoppable, Duras left her mark on French letters, theater, and cinema. She produced a bibliography of fifty-three titles, though some are very short (La Pute de la côte normande is just twenty pages long). Elisabeth Schwarzkopf once said that to be a successful opera singer you have to have a distinctive voice and be very loud. By those standards Marguerite Duras was a great diva indeed.

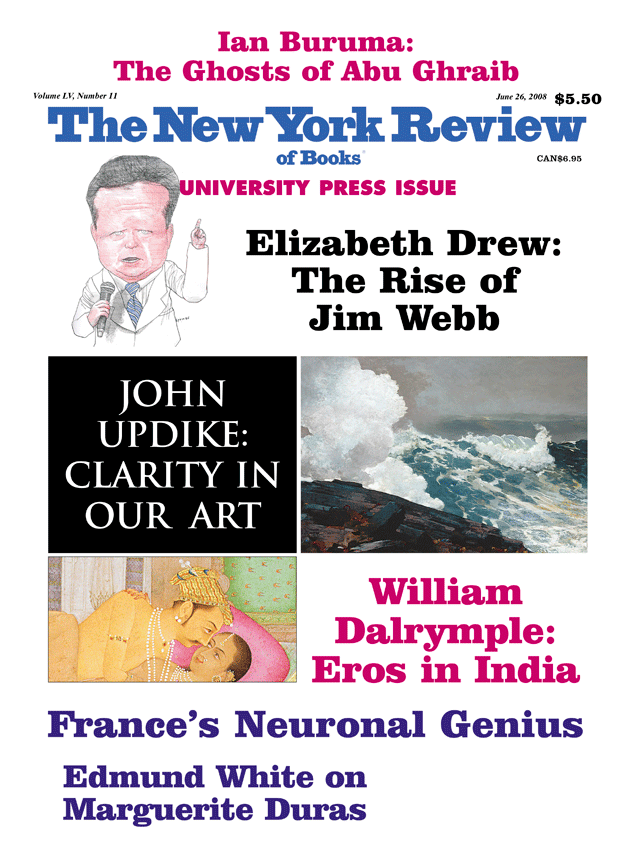

This Issue

June 26, 2008