In response to:

The Shock of Intrusion from the December 6, 2007 issue

To the Editors:

Breaking Open Japan, writes Christopher Benfey [“The Shock of Intrusion,” NYR, December 6, 2007], “can be read as a defense of the worst extremes of a hundred years of Japanese foreign policy, with responsibility shunted onto the United States.” The book says, very differently, that Commodore Perry’s bullying “obviously” wasn’t alone in spawning the “colossal” atrocities, the “hideous sadism” with which fellow Asians “were regularly tormented even more than westerners would be, when their time came to suffer Japanese occupation.”

Thus were my suggestions—principally that the history of the Pacific would surely have been less unpacific if Japan had been left to open on its own, in keeping with its wants and wishes—stretched to bêtise. Stating that a near century of preparing for and making war followed Perry’s immensely traumatic visits of 1853 and 1854 and that some Japanese long nursed resentment of the humiliation he inflicted is far from making the foolish argument that Japan’s only recourse was to attack Pearl Harbor. I submitted that the resentment was a factor in Tokyo’s decision. “Surely the plots, strikes and sadism would have been less likely [new emphasis] to develop, at least with their ardor, without him.”

Many misleading statements accompanied that key distortion. I didn’t suggest that empires based on trade (as if warships and marines never boosted the American variety) were “as pernicious as those based on territorial expansion.” Rather than “blur the distinction between brandishing guns and firing them,” I drew it repeatedly while quoting Japanese participants about one common effect in panicked Edo (later Tokyo), Perry having convinced its rulers that he—who beamed when his big guns prompted fear on Japanese faces—would fire unless they bowed to him. And stating that the Japanese were “deeply divided” about how to respond to his demands scrapped my abundant evidence that the overwhelming majority with a political voice loathed the thought of submitting to them, opening the country his detested way.

Another matter was obscured. Hailing American virtue, a writer recently found it “worth remembering” “that the United States did not occupy Japan.” Although it was accepted in 2003 that imperialism is one state imposing its will on another, acquisition of territory not required, the Perry admirer also lauded him for coming “in search of treaties, not territory.” The words quoted here—and in Breaking Open Japan—are from Professor Benfey’s The Great Wave.

The nondisclosure of personal interest came with that implication I proposed that virtually unarmed Japan had to embark on its furious militarization in response to Perry and America’s cruelly unfair treaties that followed. My suggestion was that totally natural resentment played some role in the ugly transformation. Nor would anyone sane have justified Japan’s “repugnant denials of accepted historical facts” such as using the sexual slaves of World War II and forcing civilians to kill themselves. What fantasy!

Perry cloaked his chief motive—to make Japan’s coal, his day’s oil, available to American steamships engaged in the lucrative China trade—in enduring humanitarian rhetoric. The intruder who commanded a quarter of his country’s navy was “serenely convinced,” a scholar recently summarized, that he was “bringing civilization to a benighted land”: highly cultured Japan. His pronouncements about America’s need to beat potential enemies to the punch and to acquire bases abroad (of which we now have some seven hundred) might have served as material for Dick Cheney.

Professor Benfey’s citing of the failure of a predecessor named Biddle to do the American job without applying force as argument-clinching vindication of Perry smacks of resolve to see the most important event in modern Japanese history from the American side only, which is what I sought to remedy. Japan indeed rebuffed Biddle (as I of course described), but was it not entitled to do that, to remain closed if it chose to? Or was that for Perry to decide?

“But surely,” the review concludes, “the kind of generous exercise of power [Ralph Waldo Emerson] calls for…would be in the world’s interest as well.” Even if proud Americans can picture a flicker of generosity in Perry’s cannon that terrified the essentially undefended Japanese, that terrorizing caused the latter great pain. Rather than imagined exercises of power, the one my book attempts to describe opened the way to tragedy for both countries.

George Feifer

Roxbury, Connecticut

Christopher Benfey replies:

Despite Mr. Feifer’s italicized qualifications (“resentment was a factor,” “resentment played some role in the ugly transformation,” etc.), his letter displays some of the same tendencies that troubled me in his Breaking Open Japan. My claim that he blurred the distinction between brandishing guns and shooting them was based on such passages as the following: “Perry gave neither time nor respite from brandishing guns in a way that had much the same emotional effect as firing them.” By “non-disclosure of personal interest,” I assume Feifer means that I should have mentioned that I am quoted adversely in his book. My remark about Perry seeking treaties rather than territory does not come from The Great Wave, however, but rather from an Op-Ed piece in The New York Times, which Feifer glosses as follows: “But territorial acquisition is irrelevant to imperialism.” Feifer’s aside regarding Dick Cheney confirms my impression that his book is as much about our current predicament in Iraq as it is about Perry’s incursion into Uraga Bay.

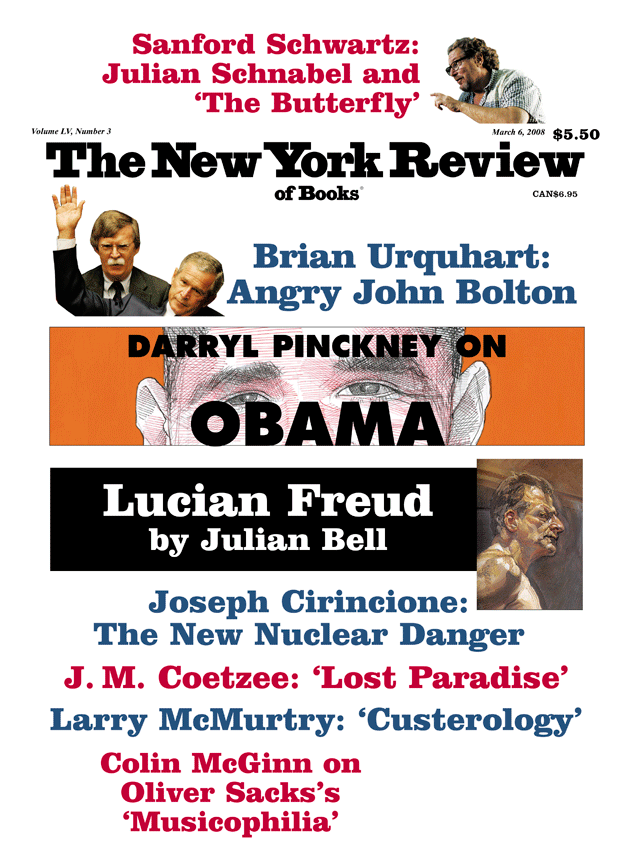

This Issue

March 6, 2008