For some readers, the books under review may be a cause of anxiety and alarm. Arachnophobia, Paul Hillyard tells us in The Private Life of Spiders, “is the most prevalent of all animal phobias.” Such intense fear of spiders can afflict almost anybody, and can become so extreme that one sufferer confessed that he “couldn’t even write the word spider,” or “go into a room until someone else had checked that there were no spiders inside.” Snakes can set off a similar reaction, and it’s the vivid descriptions and hundreds of close-up color photographs of legless and eight-legged creatures that may put off some readers. Yet I wish that they could overcome their irrational fears, for the phobic are deprived of the pleasure of contemplating nature’s foremost living gems.

Before his retirement Paul Hillyard was the curator of spiders at the Natural History Museum, London. I have known a few spider curators in my time, and they can on occasion be troublesome. For more than fifteen years I was the curator of mammals at the Australian Museum in Sydney, and my office was located between that of the nation’s foremost snake expert and the museum’s curator of spiders. Accidents do happen in museums, and I have on occasion found myself sitting at my desk not suspecting that a live snake lurked in my filing cabinet. Yet it was the rather eccentric habits of the curator of spiders that most unnerved me. I don’t count myself as a great arachnophobe, but on occasion, when dashing out of my office door on some urgent errand and bumping into the curator, whose hands were full of deadly Sydney funnel-web spiders, I admit to being discomforted.

He was a delightful fellow to be sure—bearded, gentle, and erudite—but I dreaded visiting his office, for aquariums containing live spiders had been crammed into every corner, and the walkways between them were so narrow that the room seemed transformed into a den of oversized, hairy-legged monstrosities. Worst of all, he was so fond of his charges that whenever I crossed his threshold he would invariably reach into an aquarium and enthusiastically wave his latest acquisition in my face.

Hillyard is a true spider devotee, and he cheerfully informs us that there is no escape from his subject, for our world boasts 38,000 named species of spiders, and perhaps as many again await formal description. Spider curators don’t have to look far to find their charges, for spiders are ubiquitous. In the 1930s the arachnologist W.S. Bristowe calculated that over two million spiders lurked in every acre of flower-filled meadow in England’s southeast, and that Britain’s spiders then consumed annually a bulk of insects that exceeded the total weight of the country’s human population. Today, human population growth and the use of insecticides have doubtless altered this impressive equation, but the basic fact prevails that spiders can be found almost everywhere. The Private Life of Spiders is a stroll through their largely hidden world, highlighting the most spectacular, unusual, and instructive of the eight-legged brethren.

After a brief overview of spider evolution and biology, Hillyard launches into the meat of his subject—a sweeping overview of spider diversity, commencing with those species whose habits and bodies are the most primitive, and culminating with those paragons of arachnid evolution, the elegant orb-weavers. The captions of some of the more prominent photographs give some idea of what’s in store for the reader: “Yellow crab spider with prey larger than itself”; Wolf spider (Lycosid) with orange jaws”; “Regal jumping spider. An exceptionally hairy spider.”

Enumerated also are the many spiders that are night-crawlers. Of Europe’s night-crawlers, the mouse spider with its “grey, furry body” is the one most likely to be encountered by humans, for it is a nocturnal creeper on stone walls, and appears to be alarmingly common. Arachnophobes may well refrain from nocturnal wanderings among stone walls, but even a refreshing dip in a European pond is not without its dangers, for water spiders, which possess monstrously outsized fangs capable of subduing small fish, commonly lurk there. Even a stroll on the seashore is not entirely safe for, as Hillyard almost gleefully informs us, there can be found semi-marine spiders that haunt rock pools.

Spider webs are far too fragile to have survived as fossils, so arachnologists look to the diversity of living species for clues about how they evolved. Unsurprisingly, the most primitive living spiders—the so-called giant trapdoor spiders of Southeast Asia—make a web that consists of a silken tube which the spider lives in, and which has at its entrance a series of threads that act as tripwires. Beetles or other insects stumble over these tripwires and so alert the predator lurking below to the presence of a potential meal.

Advertisement

From this system evolved the tangled, messy structures built by the daddy long legs spider. Almost everyone with a damp cellar or unused corner of a room must be familiar with the webs of these creatures, for entire communities build up in such neglected places. Stumbling upon such a mess of webs can be disconcerting, for disturbed daddy long legs spiders communicate with one another by bouncing vigorously, sending vibrations through the entire interconnected web tangle. Hillyard lists as an urban myth the belief that these minuscule creatures have the most potent venom of all spiders; for while their venom is doubtless potent, there are no recorded bites—the fangs being too small to penetrate human skin—so its mordancy remains untested.

From these untidy beginnings evolved sheet-web spiders, and finally the magnificent orb webs that, bedecked with dew, add so greatly to the beauty of an autumn morning. Such webs can be ornamented with special, highly visible silk structures known as stabilimenta whose function is still debated. They may cause birds to avoid the webs, or may, by reflecting ultraviolet light, help spiders to attract insects. The diversity of webs seems endless. Some spiders make ladder webs up to four feet tall. These are far more effective than orbs for catching moths, because moths are covered in loose scales that prevent them from sticking to webs. It is only when they lose most of these protective scales through tumbling down a ladder web that they are finally caught.

Other webs are reduced to a single thread, ornamented with sticky globules that are twirled like a bolas. One genus, the Australian Arkys spiders, has done away with webs altogether. They appear to attract male moths by producing pheromones—chemical substances secreted externally—that mimic those given out by female moths, and then grab the duped males with their spiny legs. Perhaps the most remarkable webs are those made of the extremely fine silk called cribellate. They are not sticky but instead work by entangling the legs of insects, and are perhaps the original form of Velcro.

The sex life of spiders is of course infamous: almost everyone has heard of the female black widow, which consumes her mate after sex. But who would have guessed that “bondage, rape, chastity belts, castration, and suicide” were also part of the sexual practices of spiders? Hillyard gives detailed examples of all of these practices, and his description of spider bondage is particularly intriguing:

The male European crab spider… approaches tentatively but, when close to the female, grabs one of her legs. Initially she struggles but later calms down as he moves over her body trailing silk threads, which bind her to the ground. He then lifts her abdomen, crawls under and inserts his palps [the organs that carry his sperm]. However, this bondage appears to be purely ritualistic because it is not difficult for the female to break free: it is likely that it helps to pacify her.

More touchingly, mother spiders also practice self-sacrifice. Australian crab spiders of the genus Diaea lay a single cocoon full of eggs (most spiders lay many more eggs), which they tend carefully. When the young hatch the mother spider feeds them with insects she has caught herself, until winter brings an end to easy prey. Then, unable to nurture them further, she offers them one last meal: herself.

Even the moderate arachnophobe may wish to avoid Hillyard’s chapter “Tarantulas and Trapdoor Spiders.” By way of introduction he says:

Called tarantulas in the Americas, bird-eating spiders, mygales or Vogelspinnen in Europe, baboon spiders in Africa, earth tigers in southeast Asia, mata-caballos (horse-killers) or araños peludas (hairy spiders) in Latin America, these are the large, well-built members of the family Theraphosidae. They have heavy jaws projecting forwards and they rival in size the biggest land invertebrates.

These are the spiders of nightmares, and extraordinarily large close-up photographs of these formidable creatures adorn every page.

Until recently the goliath tarantula of Amazonia was believed to be the largest spider on earth. Then someone collected an enormous spider in the remote rain forests of southeastern Peru. Its body was almost four inches long, and its legs spanned almost ten inches. It is said by those familiar with these near-mythical beasts that up to fifty share a single burrow, and that they cooperate in the hunt. Hillyard’s clinical description of this new and as yet unnamed discovery (though it has been called araños pollo, chicken spider) has embedded within it the stuff of nightmares. I can imagine the scientist intent on studying them struggling through precipitous country and an endless tangle of roots, vines, and thickets as he forces his way toward their habitat. And then, in a sudden silence, he hears the drumming of countless hairy legs on dried leaves as the colony erupts from their abode. Though just how the spiders “cooperate in prey capture to overcome larger animals” is perhaps best left unimagined.

Advertisement

The Theraphosid family of spiders also includes the notorious Sydney funnel-web, which is one of the world’s most dangerous creatures. Its distribution centers on the city of Sydney, Australia’s largest and most densely populated metropolis. Thus far, the human population seems to have had little impact on funnel-web numbers, for they abound in rock gardens and damp, shady places, even close to the city center. It is a pugnacious creature, made doubly dangerous because during the breeding season the males leave their burrows and wander to find mates. They can enter houses, where they love to lurk in slightly damp places, such as a towel casually dropped on a bathroom floor or a toddler’s clothing.

Their fangs are large enough to penetrate the skull of a small mammal, or a human fingernail, and they will bite repeatedly and deeply, soaking the wounds with their highly acidic venom. Immediately plunged into excruciating pain, the victim is soon convulsing in a lather of sweat and foaming saliva. Blindness, nausea, and paralysis follow, and while it can take an adult thirty hours to die an agonizing death, infants so bitten have just an hour to live. Thankfully, an antidote has now been devised, and deaths are now far rarer than previously.

There is a remarkable thing about this most dangerous of spiders. Like all spiders (except perhaps the giant colonial spider of Peru), it does not want to waste its venom on biting humans. Venom is metabolically expensive to produce, and a depleted supply may mean a lost opportunity to feed. Because venom evolved to help subdue prey, and because spiders have specialized diets, most venoms are rather specific in their effect. That of the Sydney funnel-web is relatively harmless to most mammals, including dogs and cats, but for primates (such as monkeys, apes, and ourselves), it is formidably deadly. Australia is a land of marsupials such as kangaroos, and there never was a primate resident there until humans arrived from Asia around 45,000 years ago. This is far too recently for evolution by natural selection to have resulted in a human-specific venom. Rather, it seems that the horrible capacity of the funnel-web to kill us is an accident of chemical evolution, while the fact that its distribution centers on Australia’s largest city would appear to be nothing short of a celestial bad joke.

The enigma of the Sydney funnel-web set me thinking afresh about arachnophobia. Why do so many of us react so strongly, and with such primal fear, to spiders? The world is full of far more dangerous creatures such as stinging jellyfish, stonefish, and blue-ringed octopi that—by comparison—appear to barely worry most people. As for the real killers—fatty foods, lack of exercise, and cigarettes—we seem to love them. Humans, along with their fears and loves, evolved on the savannas of Africa—far away from our present habitats, and it is in Africa that our primal fears were created, out of evolutionary experiences that killed the fearless and spared, sometimes at least, the fearful.

Hillyard believes that arachnophobia commences in childhood. Infants are not usually afraid of spiders, but as they get older their fears increase. Paradoxically, as adults, many recover from their fears. One could deduce from this that at some time in our evolutionary history considerable mortality was inflicted on children, as they played in the sand and mud, by a venomous spider. That spider, of course, would have to have lived in Africa, where we evolved. Is there any evidence for the existence of such a creature? Extraordinarily, there is. The six-eyed sand spider can be found in the more arid western half of southern Africa. It is a reclusive, crab-like species that buries itself in the sand and ambushes prey that wanders too close. Sand grains adhere to it, providing a natural camouflage.

Laboratory assays of the venom of this cryptic creature reveal that it is extraordinarily potent, leading to widespread blood vessel leakage and tissue destruction. We can imagine families of early humans, camped in the sand dunes of southern Africa, their children playing and scrambling in the sandy soil. Infants of course would remain safe in their mother’s arms, but toddlers through to early teenagers would be exposed to a bite from the cryptic six-eyed sand spider, and we have seen how quickly children succumb to spider venom. For arachnophobia to have become the most nearly universal of all of our animal phobias, our ancestors, who managed to avoid being bitten in childhood, must have been properly cautious of the eight-legged creatures.

Snakes can elicit a similar response, though in Life in Cold Blood Sir David Attenborough describes them so beautifully, and as such gentlemanly creatures, that it’s hard not to admire them. Indeed, there is little doubt in my mind that Sir David is entirely enamored of them. You might think the term “gentlemanly” hardly appropriate for a venomous serpent, but consider the cobra. Deaf (as with all snakes they lack external ear openings), all but dumb, and with eyes of a rather defective structure, they have nevertheless devised a way to warn us and other large creatures of their presence. Why do you think they have that expandable neck with its brightly colored scales—the cobra’s hood—if not to give a warning? We are not snake food, and encounters between snakes and large mammals can be bad for the snake as well as us. They could be trodden upon and injured, or may be forced to use some of their precious venom to defend themselves. In short, everyone—both biter and bitee—loses from snakebite, so there has been strong evolutionary pressure for snakes to evolve means of warning larger mammals that they are near, and should be avoided.

The largest venomous snake on earth is the king cobra. An inhabitant of South and East Asia, it grows to eighteen feet, and if threatened can rear up to the height of a man, erect its hood, and growl loudly. It is unique among snakes in making a nest of leaves for its eggs, which it will defend against all intruders. Even elephants need to give it a wide berth, for so potent is its venom that it can kill these largest of creatures with a bite to the trunk. Such a serpent might seem a nightmare to those scared of snakes, but it does have a positive side, for it feeds solely upon other snakes, including venomous kinds such as other cobras.

North America is home to an altogether less terrifying kind of venomous snake, which also warns us of its presence. The rattlesnake’s rattle consists of hollow scales that accumulate at the end of its tail each time it sheds its skin. When the snake vibrates its tail—which it does at around fifty shakes per second—a loud and characteristic sound is generated, which can be heard from as far as one hundred feet away.

Apart from fleeting encounters, the lives of rattlesnakes are largely hidden from us, and only Sir David and his colleagues have spent sufficient time among them to penetrate their veil of secrecy. In Life in Cold Blood Attenborough writes of filming a timber rattlesnake as it hunted in the woodlands of upstate New York, revealing an entirely unexpected dimension in reptile intelligence. The snake was found

lying curled beside a boulder in the underbrush. It was barely more than a metre [three feet] long and lying neatly coiled with its neck drawn back into an s-curve and its head resting on its flank. Its back was patterned with large brown chevrons placed with such regularity along its length that you might think they would make it conspicuous. But not so. It was almost invisible…. We set up an electronic camera specially adapted to produce pictures in minimal light. To this we attached sensors that would detect any major movement….

We did this for several nights without managing to record anything of significance. The snake we had chosen was waiting curled up alongside a dead branch that crossed the picture diagonally. It was investigating the branch and that action had turned on the camera. With its neck outstretched, it flickered its tongue along the whole length of the branch and then up a leafy little sapling that was growing alongside…. Most rodents use the same trails as they run across the forest floor…. The snake settled itself back with its neck in an s-bend and its head resting on its flank an inch or so from the branch’s middle section. The camera switched itself off.

Once again, the recorder switched on. This time it had been activated by a mouse that was sitting at the far end of the dead branch. It looked around inquisitively, twitching its whiskers. The snake, a mere foot or so from it, remained as motionless as stone….

Having apparently reassured itself that all was well, the mouse sauntered down the branch and right past the snake. To our surprise, the snake remained immobile and the mouse disappeared. Seconds passed. The snake flickered its tongue and readjusted the position of its head. It was as if it had now noted the exact route that mice followed through this patch of ground and was making the last refinements to its attacking position…. Then the recorder switched off….

But then it started once again. Another mouse was standing in exactly the same position as the first at the end of the branch. It too started to walk down the log—and in a flash the snake struck …its mouth gaping widely, its two needle fangs projecting directly forward. They stabbed the mouse in the flank and in the same instant withdrew.

Such careful observation and love of nature are the hallmarks of Sir David’s work. His latest book, Life in Cold Blood, covers far more than snakes, being an investigation of all amphibians and reptiles, and it is the latest in a series of projects that have covered almost all life on earth. Sir David is now in his early eighties, and the arduous nature of his work suggests that this may well be the last of his great ventures into nature. Being devoted to the less lovable cold-blooded, scaly, crawling creatures, it might reach a smaller audience than his previous works. But for pure passion, interest, and engagement, in Life in Cold Blood, Sir David has left the best wine for last.

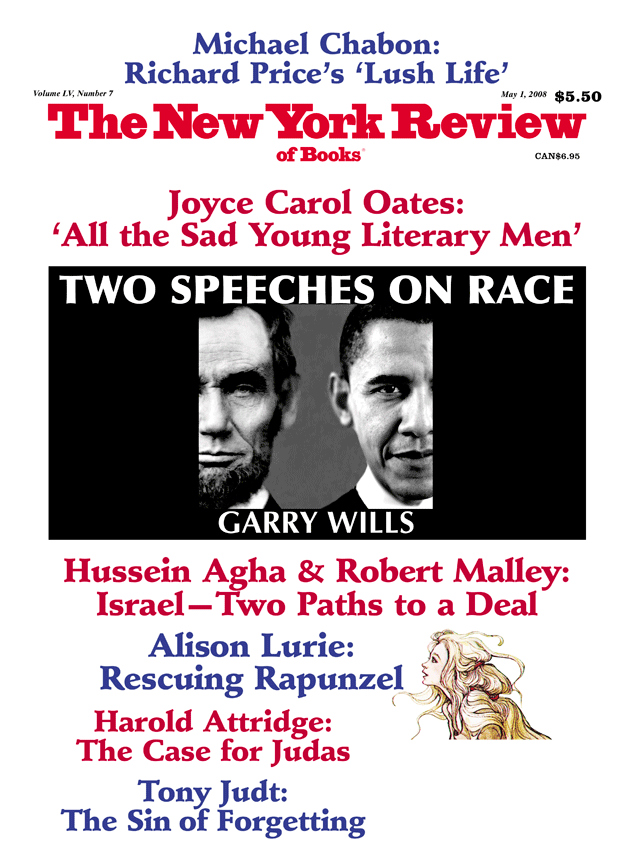

This Issue

May 1, 2008