Only recently has the situation outlined by Steven Greenhouse in his new book,The Big Squeeze, been getting serious attention from politicians. Average wages for American workers have been largely stagnating for a generation. Some six million more Americans have no health insurance today than did seven years ago. The distribution of income in the United States is as unequal as it was in the Roaring Twenties. With the country facing a possibly deep and painful recession, unemployment rising, and mortgage defaults at record levels, the poor state of the economy is finally high on the list of American concerns and is the leading presidential campaign issue.

But Steven Greenhouse, the labor reporter ofThe New York Times, has a still more disturbing story to tell. He shows how the nation’s businesses have illegally, callously, and systematically abused their workers in a time of increased global competition and technological change, while government protection of workers’ rights has significantly weakened. Greenhouse writes about factory employees and retail clerks, truck drivers and store managers, computer technicians, middle managers, and engineers. They all face similar difficulties: they have lost their places in what was once a secure and confident middle class. The longstanding distinction between the blue-collar and white-collar worker has been blurred. Good blue-collar jobs are disappearing rapidly as manufacturing industries decline; but many new white-collar jobs pay poorly, provide minimal health care and pension benefits, and offer little job security. There is now no privileged segment of earners in the nation except the upper 10 percent or so.

Greenhouse finds managers of countless companies, many of them well known and admired—not only Wal-Mart but JPMorgan Chase—who willfully break the law to reduce labor costs. As a matter of company policy, they have adopted harsh management techniques to sustain—at least until the current downturn in the economy—enormous profits. An excellent and relentless reporter, Greenhouse has not gone out of his way to uncover horror stories. He has attempted to find representative examples from the lives of workers. Barack Obama was much criticized by his Democratic colleagues when he said workers were bitter. They should read the stories of shameful treatment in Greenhouse’s book.

Kathy Saumier’s is one of those stories. She was hired as an inspector on the production line of Landis Plastics, a manufacturer of containers, whose new factory was near Syracuse, New York. Saumier, who had dropped out of high school at sixteen to help support her single working mother of five, thought she had at last found the job that would offer her security, decent benefits, and adequate pay.

But the Landis company, it turned out, had an unusually high percentage of severe accidents by industry standards, and when Saumier tried to address the problem, she came to be seen as a dangerous troublemaker. A close friend of hers lost a finger, and there were similar accidents. Many employees were often required to work twelve-hour days or on weekends, and were given demerits whenever they missed a day of work or left early, even when they had to deal with a serious emergency or a genuine illness. As demerits accumulated, Landis docked their pay. Almost all the low-level jobs were held by women, but only one of the higher-level jobs was, and women complained often of sexual harassment.

Saumier came to believe that only a union could get management to respond, and she started trying to organize her fellow workers. She also filed complaints about job safety with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and a sexual discrimination suit with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

As Saumier’s organizing activities drew more attention, Landis tried to discredit her. First, the company accused her of tampering with the brakes on the car of a worker who opposed the union. The accusation did not hold up. The company then accused her of tampering with the lights of the car of another anti-union worker. A mechanic said the car simply had a faulty sensor light. She was at last removed as an inspector and given a job in which she was isolated in a room by herself.

When these tactics failed to get her to quit, she was called in by a Landis “human resources manager” and told that she had been accused of sexual harassment by two male workers. One of them said she pulled down his pants and tried to fondle his genitals. She denied the charges, but Landis then fired her, making a dramatic announcement to the press about her sexual overtures.

Kathy Saumier’s attempts to organize a union had already been widely reported in the local press, however. She had earlier testified before the New York State Assembly. Bruce Springsteen visited her. When hearings were held on the sexual harassment charges, her accusers were discredited, and the National Labor Relations Board ruled in her favor. OSHA and the EEOC had also supported Saumier’s charges of safety violations and sexual discrimination. OSHA eventually fined the company $720,700 for countless safety violations and Landis agreed to pay nearly $800,000 to workers to settle charges of sexual discrimination. To the outside world, it may have looked as if Saumier won. She received a financial settlement from the company, but it took more than a year for her to be reinstated in her job. Then, soon after she went back to work, she tore her rotator cuff and could no longer keep pace with the assembly line. She eventually had to leave.

Advertisement

The union got nowhere at Landis. Greenhouse reports that the starting wages are the same today as they were ten years ago, falling well behind inflation. Women still have almost none of the high-level jobs. The average worker now pays $2,300 in annual premiums to participate in the company health care plan, much more than before. When Landis was acquired by Berry Plastics in 2003, the new firm made the demerit systems more onerous and stopped contributing to the workers’ retirement program.

Many economists now argue that the decline of unionization in America has contributed significantly to stagnating wages and reduced benefits for workers. In the 1950s, unions represented about one third of all workers. Today, they represent about one in eight, and in the private sector, only one in twelve. It is tempting to believe that Americans just don’t approve of unions. Since 1981, when Ronald Reagan broke up the striking air traffic controllers’ union, their popularity in the US has fallen sharply. Like many others, Greenhouse thinks this disastrous strike was a turning point in the nation’s attitude toward workers. But, as he writes, some 50 million non-unionized American workers, according to surveys, now say that they definitely or probably would join one if given the option.

One problem for unions is that the economy has changed. Unions became powerful in manufacturing industries, especially after World War II, where profits were strong and many companies were confident about the future. At a time when the large manufacturing oligopolies, such as the auto and steel industries, are faltering from global competition and services are in ever-greater demand, unstable, fragmented, and frightened workforces are more difficult to organize. Greenhouse also argues that the unions themselves are at fault: they do not devote enough resources to organizing; their attitudes toward business are sometimes too confrontational, lacking in analysis of the concerns and strategies of management.

To Greenhouse, however, the biggest obstacle is posed by aggressive and often illegal anti-union tactics, like those Landis used against Kathy Saumier. Managers have made opposition to unions into an illegal art. In the 1960s, there were, Greenhouse reports, perhaps a hundred professional “union avoidance” consultants in the United States. Today, there are more than two thousand. In a separate study, two economists, John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer, found that illegal firings of workers trying to organize unions, a common practice, rose sharply in the 1980s and again in the 2000s.1The federal government is required by law to protect union organizers but it consistently fails to do so. The fines levied by the NLRB have long been meager. Meantime, management actions against unions are supported by the nation’s courts. In 2007, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that companies can bar union organizers from setting foot on their grounds.

Violations of minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws are increasing. Immigrants are especially easy targets, even though they are protected by the federal and state wage and hour laws. Julia Ortiz, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic, landed a job at a retailer called Save Smart in New York City. She worked for $35 a day for three years, six days a week, her pay typically coming to $210 a week. She couldn’t afford to buy her kids the food they needed, she told Greenhouse. When she and her children were sick they went to a crowded local clinic. Had she earned the legal minimum wage as well as time and a half pay for overtime, as is required by law, she would have taken home $414 a week. But like many other workers at Save Smart, she was hesitant to complain because she had no green card. An advocacy group finally encouraged Ortiz to file complaints with the Labor Department, and they ruled in her favor. Save Smart settled the case with Ortiz for $52,000 in back pay.

Few workers have Saumier’s or Ortiz’s tenacity. The government, Greenhouse found, is simply looking the other way. Three decades ago, there were more federal wage and hour inspectors than there are today, though the labor force was 40 percent smaller. Retailers, fast-food restaurants, and call centers have become the new sweatshops, and federal inspectors seldom visit them. Delivery men at Manhattan’s Gristedes and Food Emporium grocery store chains often have to work as many as seventy-five hours a week, earning less than $3 an hour. Employees told Greenhouse that managers at Toys-R-Us, Wal-Mart, Pep Boys, and Taco Bell, among countless others, erase hours worked from the time clock in order to reduce their pay or make them work illegally long hours.

Advertisement

Workers at some call centers are regularly docked for every minute they spend in the bathroom, according to Greenhouse. Wal-Mart and others have become notorious for locking in night-shift workers, often forcing them to work longer hours. A careful study in 2007 of workplace practices in New York City by three economists found violations of labor laws were widespread. Pay of $3 an hour, they report, is hardly unusual, although the New York State minimum wage is now $7.15 an hour.2

Particularly disheartening is the story, recounted by Greenhouse, of Drew Pooters. Pooters joined the air force right out of high school in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and during fourteen years, some of it as a logistics specialist, with stations in Saudi Arabia and Somalia, he rose to staff sergeant. “It was the Reagan years, and everyone was worried about the evil Communists, and most of the guys in my class enlisted,” he told Greenhouse. “That’s the kind of place Bartlesville was.”

When he got out, Pooters entered the US job market for the first time in his life. He worked at two Wal-Marts, and then found a better job with the help of his father, a software engineer, running a gas station owned by Phillips Petroleum. He often worked sixty hours a week but bonuses promised by Phillips never came. He then optimistically joined a Toys-R-Us in Albuquerque, where he was hired as the manager of a department. He liked the job but it didn’t take long before he found that an assistant manager was reducing the recorded hours worked by his employees on the company computer. A few days after he complained to the assistant manager about the practice, Pooters was demoted to stocking shelves.

He placed his resume on Monster.com and found a $26,000-a-year job at Family Dollar, another discount store, as a manager-in-training. He rose quickly to become manager, but he was now required to cut back the hours worked by his employees. And he found he had to put in fourteen- to sixteen-hour days to keep up with the work they would ordinarily have done. A father of four, he needed the job. But then Pooters found that his district manager also was jiggering the time records of his employees. He felt he had to leave and eventually joined Rentway, a rent-to-own retailer near Detroit, where he and his wife decided to move. Rentway also demanded that he falsify the recorded hours worked by employees. Pooters balked and was ultimately fired. After much inquiry, Greenhouse found that not only was Pooters’s story true but that illegally cutting back hours was a common practice.

Millions of Americans now work under the kinds of conditions to which Pooters objected. Some 50 million Americans are members of households—consisting of one or more workers—that earn in total between $20,000 and $40,000 a year. The jobs they get usually provide no health care or offer a plan that is prohibitively expensive. In 2005, some 40 percent of the people in these working households had, for some period of time, no health insurance. Approximately 13.5 million Americans are even worse off. They live in families whose total income is below the poverty line even though at least one family member works full-time. The federal poverty line for a family of four is slightly above an annual income of $20,000. Many of these are people of color, an issue Greenhouse does not address sufficiently.

But the abuses are occurring higher up the income scale. At JPMorgan Chase, the giant international bank, a worker reported that management balks at paying time and a half for extra hours. Her coworkers, she told Greenhouse, just stopped asking for it for fear of angering their bosses. At such highly regarded companies as Microsoft, Hewlett Packard, Intel, and Verizon, hiring temporary help who stay on almost permanently to do high-level and often sophisticated jobs is a conventional business practice aimed at reducing the payroll. The “permatemps,” as they are now called, don’t get the health care, retirement, and other benefits of permanent workers. As one of the workers tells Greenhouse, “If Microsoft cannot afford to treat all its employees well, then no company in the history of the world could [sic].”

A high-technology company called WatchMark, which makes software for cell phone operators, fired eighteen of its engineers with no warning. It then told them that in order to receive their month’s severance pay, they had to stay on the job and train their low-cost replacements from India. When Northwest Airlines laid off workers, it gave them a booklet called “101 Ways to Save Money.” One piece of advice was not to be shy about taking something you like from the trash.

Over the past decade, the failure of the economy to raise wages has become undeniable. Until recently, both corporate profits and the nation’s productivity—to which economists have traditionally linked wages—have risen strongly. Although the value of corporate benefits such as health care have risen somewhat faster, the median full-time worker’s wage still amounts to some $38,000 a year, only marginally higher than it was in 2001. Median family income is about $1,000 lower than it was then.

This situation may now be getting more attention, but it is not new to the 2000s. The real wages and salaries of the median full-time male worker in his thirties with a high school diploma are down steeply from levels reached at the beginning of the 1970s. But even those with college degrees have not fared especially well. For example, for men between twenty-five and thirty-four with college degrees, median earnings, according to Census Bureau data, are up only marginally, by about 3 percent. For women of the same age and education, median earnings have risen more rapidly, by about 20 percent, but this is an annual rate of gain of only 0.5 percent. And despite the increase, women working full-time with similar educations still make only about three quarters of what men with similar educations earn. Family incomes have risen modestly over this period largely because spouses work many more hours.

Economists’ statistical techniques are not refined enough to analyze unambiguously the causes of this long-term stagnation. But with the exception of some labor economists like Lawrence Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute and Annette Bernhardt of the National Employment Law Project, few economists are talking about the lawless-ness of employers and their abuse of workers, which combine to keep wages down. Besides the everyday practices described by Greenhouse, there have been, during the last ten years, many examples of corporate malfeasance, of which Enron’s crimes are only the most glaring. Prestigious brokerage firms, consultants, lawyers, and accountants all had a part in Enron’s scams, which resulted in severe financial hardship for employees who had been encouraged to invest their retirement savings in Enron stock. Hundreds of mutual funds have conceded that they favored their best customers at the expense of others. Mortgage companies have now been found to have been negligent and culpable in signing up millions of homeowners who were unable to pay the debt service on their loans, and major banks recklessly invested in complex new securities whose creditworthiness they never fully understood. All the while, the executives at these companies paid themselves remarkably well and have, with few exceptions, not been held accountable for these problems.

Such concerns almost never enter the calculations of economists about growth, although clearly such practices can have serious effects on the economy. We now see that reckless mortgage lending may cause a severe recession. But there are more subtle issues. For example, generous stock options given to high-ranking business executives create incentives for them to influence the stock price by sharply cutting labor costs. This may raise short-term profits but may do so at the expense of developing a well-trained and stable labor force for the future. CEO compensation could be easily linked to long-run profits if corporate boards saw fit to do so.

Of course, there are, as Greenhouse observes, large external forces that have been putting heavy pressure on business, the favorite culprit being globalization. One often senses a resigned acceptance among policymakers and academic experts of the inevitability of increasing competition from lower-wage economies overseas. We frequently hear that Americans are now competing with low-paid laborers from China and India, and how the US loses millions of good manufacturing jobs in the process. America has lost 3.5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000 alone, Greenhouse reports.

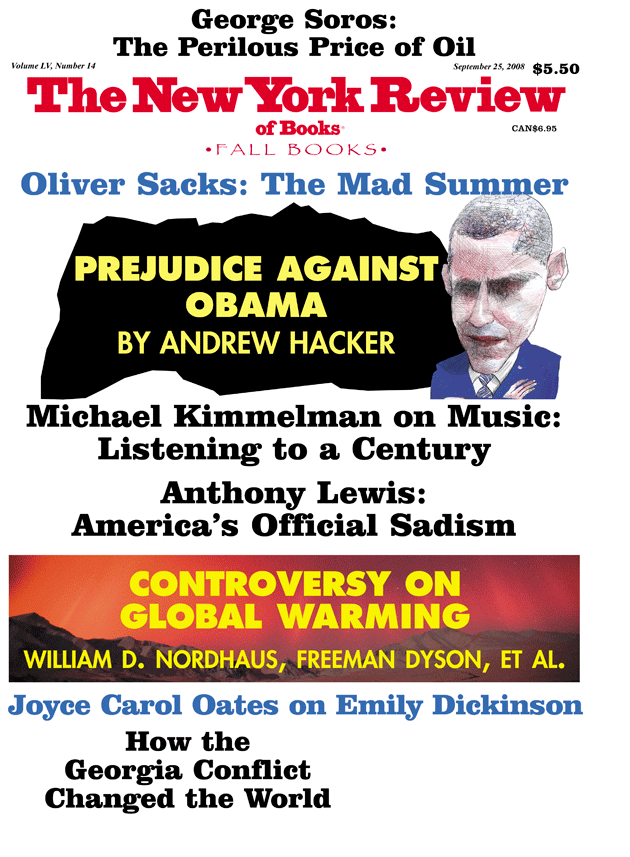

Barack Obama has said he would tighten agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement in order to give more protection to American workers. But in later comments he also said he will seek to open up foreign markets to American manufacturers, presumably by encouraging lower tariffs, and convince Americans of the value of globalization. John McCain, his presumptive Republican opponent, remains completely committed to free trade.

Many proponents of free trade, including former Treasury secretaries Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers, argue that instead of restricting imports, the US should improve the domestic safety net to protect those who lose jobs from overseas competition. The reforms generally proposed include expanded unemployment insurance, job training programs, job search initiatives, and a higher minimum wage. Obama has endorsed many of these ideas. McCain, by contrast, though he has made comments about improving the unemployment compensation system, in fact supported a Republican filibuster of the 2007 minimum-wage hike eventually passed by Congress.

Economists also argue that technological advances require more skilled workers, while Americans are being inadequately educated. The quality of K–12 education is highly unequal; the gap in pay between those who go to college and those with only a high school diploma, though lower recently, has risen rapidly during the past generation. And though few seem to have noticed, the rate of college attendance has leveled off. The economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz argue that technological advance and the demand it makes for better-educated employees account for most of the nation’s growing inequality. In a valuable new book that traces the history of American education over the past two centuries, they call for more government aid to students who want to attend college and for vigorous pre-kindergarten education programs. 3

Few will disagree that making education more available and improving its quality will be critical to future economic growth. But the presumption that raising educational attainment in America is the principal answer to the nation’s poor wage performance is being increasingly challenged. (Saumier, Ortiz, and Pooters, incidentally, did not go to college.) To take a single example, the economists David Card and John DiNardo observe that much of the large increase in income inequality took place in the early 1980s. Yet technological advances continued and perhaps even increased in the 1990s. If technological advance was producing more demand for educated workers, why didn’t inequality rise as rapidly during the 1990s as it did in the early 1980s and the 2000s? 4

Economists at the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington think tank, have been raising similar questions. They note that income inequality is rising rapidly among the college-educated as well as high school graduates. Something else is going on besides globalization and changing technologies. Card and DiNardo, for example, argue that the failure to raise the minimum wage since the 1970s to keep up with inflation may have had a large impact on overall inequality, especially in the 1980s.

Greenhouse’s book gives a convincing portrait of a business culture that has been more and more aggressive toward workers. He quotes a management consultant who makes a telling comparison between the 1960s and the present. In the earlier period, he says, “your reputation was on the line if your hire didn’t work out. So you did everything you could to make them better. Now, your reputation is on the line if you don’t get rid of them fast enough.” A 1990s survey by the Conference Board, which represents large US companies, found that “employee morale ranked eighth out of a possible nine management priorities.”

There are notable exceptions. The discount retailer Costco, Greenhouse reports, may well charge lower prices for goods than Wal-Mart on average but pays its workers significantly better. A company like apparel maker Patagonia offers paid maternity leave and on-site child care, among other benefits. Often the companies find that their generous labor policies result in better performance and higher profits. But Greenhouse concludes that relatively few companies treat their workers well on all counts. Some do so, he says, only because of union pressure.

To enforce existing employment laws and social programs—especially job retraining—will require a serious commitment to greater government vigilance in order to reverse the practices Greenhouse describes. John McCain’s economic position thus far is decidedly averse to new government programs or improved regulation. He supports extending the Bush tax cuts and providing tax breaks for Americans to save for their own health care. He vaguely claims that he will cut government programs to reduce the deficit. But so far at least, he has not paid nearly as much attention to economic policy as has his opponent.

Barack Obama has advocated a good many reforms, including more financial regulation, a higher minimum wage, support for labor organizing, new pre-kindergarten programs, expanded aid for college, investment in energy research, and a requirement that businesses provide benefits for retired employees. In view of these proposals, it should not come as a surprise that, asTheWall Street Journalhas recently reported, Wal-Mart has been engaging in an aggressive effort to warn its store managers and supervisors that a Democratic victory in November could result in a rapid unionization of the company’s employees. 5

But it may be that Obama is trying to touch too many bases too lightly. If he is to choose one program to emphasize, which is probably the wise political course, there is little doubt what it should be. He has proposed that business be required to provide health insurance for all full-time workers, with subsidies for small companies, or to contribute a portion of the payroll to a national health care plan for which all Americans would be eligible regardless of current or previous illnesses. Low wage workers would also qualify for tax credits to join the program. If the US can make serious progress toward a universal and more efficient health care system, it can improve conditions on many other fronts.

A nearly universal system will improve significantly the lives of lower-income workers whose jobs typically do not provide insurance or do so at prohibitive rates. If the health expenses of businesses are reduced, there will also be more room to raise wages. If the rapid rise in health care costs can be moderated through controls and oversight—and better access to preventive medical care—Medicare and Medicaid will not eat away as much of federal revenues over time, and Americans themselves will spend less of their personal income on health.

But to pursue health care reform and other projects will require higher taxes or the willingness to enlarge the budget deficit in the short run. Obama would raise both income taxes and Social Security taxes for families earning more than $250,000 a year. He would also raise capital gains taxes, though he has not specified by how much. But he would partially offset these hikes with tax cuts for the middle class and tax credits for poorer workers.

By most accounts the nation’s infrastructure is seriously deficient. Rebuilding roads, bridges, and water systems will also create necessary jobs. Obama’s solution for more infrastructure is to establish a new public bank that will receive $60 billion over ten years, to invest in roads, bridges, dams, railways, schools, and much else, creating, he hopes, as many as two million new jobs and stimulating approximately $35 billion a year in additional funding. He is also hoping for a peace dividend as the US withdraws forces from Iraq. But he will have to confront financing issues more directly if he is elected. In view of the amounts needed for health care and for rebuilding infrastructure, among other requirements, tax cuts for the middle class have no evident justification. If we take into account the likely economic payoffs from more investment in infrastructure and education, there should be more tolerance for budget deficits. And as some Democratic economists are now pointing out, there is leeway because deficits as a proportion of the American economy are significantly lower now than when Bill Clinton took office.

But as Greenhouse’s book strongly suggests, much can also be done by providing fair opportunities for unions to organize, and by seriously enforcing the labor laws and imposing harsher penalties for violating them. The Employee Free Choice Act introduced by Senator Obama, among others, will be a good test. Defeated in the Senate last year, it tried to make it easier for unions to organize in companies that don’t have one. Opponents claim it would give unions too much power to coerce hesitant employees to join. Obama now says he will sign it as president. McCain opposed it when it came up for a vote.

In the light of recent events, there is also a clear case for more effective regulation of the financial industries, not only of irresponsible mortgage lending but of fraud and misrepresentation. These changes will not cost much because the nation has much of the regulatory apparatus in place. They will help to reverse a trend set in motion early in the 1980s by the Reagan administration and its corporate supporters. Unfair and harsh treatment in the American workplace is again a commonplace, and it should not be tolerated in a country that claims to value opportunity for all.

—August 27, 2008

This Issue

September 25, 2008

-

1

John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer, “Dropping the Ax: Illegal Firings During Union Election Campaigns,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, D.C., January 2007. ↩

-

2

Annette Bernhardt, Siobhán McGrath, and James DeFilippis,Unregulated Work in the Global City: Employment and Labor Law Violations in New York City, Brennan Center for Justice, New York University, 2007, at www .brennancenter.org/globalcity. ↩

-

3

Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz,The Race Between Technology and Education(Harvard University Press, 2008). ↩

-

4

David Card and John DiNardo, “The Impact of Technological Change on Low-Wage Workers: A Review,” inWorking and Poor: How Economic and Policy Changes Are Affecting Low-Wage Workers, edited by Rebecca M. Blank, Sheldon H. Danziger, and Robert F. Schoeni (Russell Sage Foundation, 2006). ↩

-

5

See Ann Zimmerman and Kris Maher “Wal-Mart Warns of Democratic Win,”The Wall Street Journal, August 1, 2008. ↩