Download the text of the ICRC Report on the Treatment of Fourteen “High Value Detainees” in CIA Custody by The International Committee of the Red Cross, along with the cover letter that accompanied it when it was transmitted to the US government in February 2007. This version, reset by The New York Review, exactly reproduces the original including typographical errors and some omitted words.

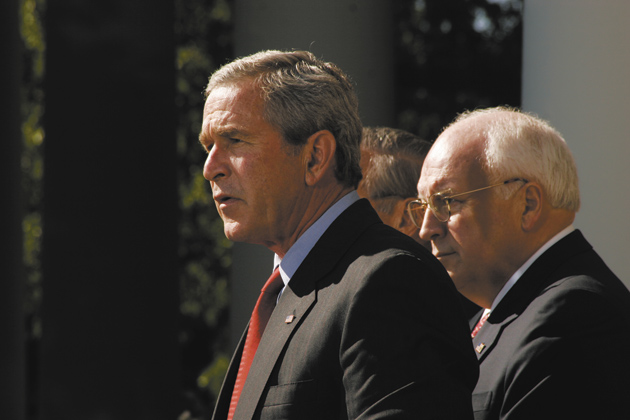

When we get people who are more concerned about reading the rights to an Al Qaeda terrorist than they are with protecting the United States against people who are absolutely committed to do anything they can to kill Americans, then I worry…. These are evil people. And we’re not going to win this fight by turning the other cheek.

If it hadn’t been for what we did—with respect to the…enhanced interrogation techniques for high-value detainees…—then we would have been attacked again. Those policies we put in place, in my opinion, were absolutely crucial to getting us through the last seven-plus years without a major-casualty attack on the US….

—Former Vice President Dick Cheney, February 4, 20091

1.

When it comes to torture, it is not what we did but what we are doing. It is not what happened but what is happening and what will happen. In our politics, torture is not about whether or not our polity can “let the past be past”—whether or not we can “get beyond it and look forward.” Torture, for Dick Cheney and for President Bush and a significant portion of the American people, is more than a repugnant series of “procedures” applied to a few hundred prisoners in American custody during the last half-dozen or so years—procedures that are described with chilling and patient particularity in this authoritative report by the International Committee of the Red Cross.2 Torture is more than the specific techniques—the forced nudity, sleep deprivation, long-term standing, and suffocation by water,” among others—that were applied to those fourteen “high-value detainees” and likely many more at the “black site” prisons secretly maintained by the CIA on three continents.

Torture, as the former vice-president’s words suggest, is a critical issue in the present of our politics—and not only because of ongoing investigations by Senate committees, or because of calls for an independent inquiry by congressional leaders, or for a “truth commission” by a leading Senate Democrat, or because of demands for a criminal investigation by the ACLU and other human rights organizations, and now undertaken in Spain, the United Kingdom, and Poland.3 For many in the United States, torture still stands as a marker of political commitment—of a willingness to “do anything to protect the American people,” a manly readiness to know when to abstain from “coddling terrorists” and do what needs to be done. Torture’s powerful symbolic role, like many ugly, shameful facts, is left unacknowledged and undiscussed. But that doesn’t make it any less real. On the contrary.

Torture is at the heart of the deadly politics of national security. The former vice-president, as able and ruthless a politician as the country has yet produced, appears convinced of this. For if torture really was a necessary evil in what Mr. Cheney calls the “tough, mean, dirty, nasty business” of “keeping the country safe,” then it follows that its abolition at the hands of the Obama administration will put the country once more at risk. It was Barack Obama, after all, who on his first full day as president issued a series of historic executive orders that closed the “black site” secret prisons and halted the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” that had been practiced there, and that provided that the offshore prison at Guantánamo would be closed within a year.

In moving instantly to do these things Obama identified himself as the “anti-torture president” no less than George W. Bush had become the “torture president”—as the former vice-president, a deeply unpopular politician who has seized the role of a kind of dark spokesman for the national id, was quick to point out. To a CNN interviewer who asked Mr. Cheney in March whether he believed that “by taking those steps…the president of the United States has made Americans less safe,” Cheney replied:

I do. I think those programs were absolutely essential to the success we enjoyed of being able to collect the intelligence that let us defeat all further attempts to launch attacks against the United States since 9/11. I think that’s a great success story.4

To which President Obama a few days later answered, “I fundamentally disagree with Dick Cheney.” He went on:

I think that Vice President Cheney has been at the head of a movement whose notion is somehow that we can’t reconcile our core values, our Constitution, our belief that we don’t torture, with our national security interests…. That attitude, that philosophy has done incredible damage to our image and position in the world.5

The President spoke of justice and reputation and the attitudes of Muslims toward Americans. And he spoke of “the facts”—which, he said of Mr. Cheney, “don’t bear him out.” It is clear that the President, a former professor of constitutional law and self-professed “optimistic guy” who, when asked whether those who have tortured should be punished, speaks of his preference for “looking forward” over “looking backward,” appreciates the political importance of the “great success story” being shaped by Cheney and others out of the recent past, a “success story” that the new president, with his overly “legalistic” concern for the Constitution, is said to be wantonly and foolishly destroying.

Advertisement

Cheney’s story is made not of facts but of the myths that replace them when facts remain secret: myths that are fueled by allusions to a dark world of secrets that cannot be revealed. At its heart is the recasting of President George W. Bush, under whose administration more Americans died in terrorist attacks than under all others combined, as the leader who “kept us safe,” and who was able to do so only by recognizing that the US had to engage in “a tough, mean, dirty, nasty business.” To keep the country safe “the gloves had to come off.” What precisely were those “gloves” that had to be removed? Laws that forbid torture, that outlaw wiretapping and surveillance without permission of the courts, that limit the president’s power to order secret operations and to wage war exactly as he sees fit.

The logic here works both ways: if “taking the gloves off” was a critical part of the “great success story” that has “kept the country safe,” then those who put the gloves on—Democrats who, in the wake of the Watergate scandal during the mid-1970s, passed laws that, among other things, limited the president’s freedom to order, with “deniability,” the CIA to operate outside the law—must have left the country vulnerable. And if by passing those restrictive laws three decades ago Democrats had left the country defenseless before the September 11 terrorists, then putting the gloves back on, as President Barack Obama on assuming office immediately began to do, risks leaving the country vulnerable once more.

Thus another successful attack, if it comes, can be laid firmly at the door of the Obama administration and its Democratic, “legalistic” policies. Especially in the case of “the ultimate threat to the country,” as the former vice-president put it two weeks after leaving office, of

a 9/11-type event where the terrorists are armed with something much more dangerous than an airline ticket and a box cutter—a nuclear weapon or a biological agent of some kind. That’s the one that would involve the deaths of perhaps hundreds of thousands of people, and the one you have to spend a hell of a lot of time guarding against.

I think there’s a high probability of such an attempt. Whether or not they can pull it off depends [on] whether or not we keep in place policies that have allowed us to defeat all further attempts, since 9/11, to launch mass-casualty attacks against the United States….

If you release the hard-core Al Qaeda terrorists that are held at Guantánamo, I think they go back into the business of trying to kill more Americans and mount further mass-casualty attacks. If you turn them loose and they go kill more Americans, who’s responsible for that?

Who indeed? Mr. Cheney’s politics of torture looks, Janus-like, in two directions: back to the past, toward exculpation for what was done under the administration he served, and into the future, toward blame for what might come under the administration that followed.

Put forward at a time when Republicans have lost power and popularity—and by the man who is perhaps the least popular figure in American public life—these propositions seem audacious, outrageous, even reckless; yet the political logic is insidious and, in the aftermath of a future attack, might well prove compelling. We are returning here to old principles, the post–cold war national security politics that Karl Rove, scarcely four months after the September 11 attacks, set out bluntly before his colleagues at the Republican National Committee: “We can go to the country on this issue”—the “War on Terror,” Rove said, because voters “trust the Republican Party to do a better job of protecting and strengthening America’s military might and, thereby, protecting America.” And in 2002 and 2004, just as Rove had predicted, Republicans gathered a rich harvest from this “politics of fear,” establishing and adding to majorities in both houses of Congress and managing to reelect a president who had embroiled the country in a deeply unpopular war in Iraq.

Cheney’s politics of fear—and the vice-president is unique only in his willingness to enunciate the matter so aggressively—is drawn from the past but built for the future, a possibly post-apocalyptic future, when Americans, gazing at the ruins left by another attack on their country, will wonder what could have been done but wasn’t. It relies on a carefully constructed narrative of what was done during the last half-dozen years, of all the disasters that could have happened but did not, and why they did not, and it makes unflinching political use of the powers of secrecy. As the former vice-president confided to the CNN correspondent John King,

Advertisement

John, I’ve seen a report that was written based upon the intelligence that we collected then that itemizes the specific attacks that were stopped by virtue of what we learned through these programs. It’s still classified. I can’t give you details of it without violating classification, but I can say there were a great many of them.

Attacks prevented, threats averted, lives saved—all secret and all ascribed to a willingness to do the “tough, mean, dirty, nasty” things that needed to be done. Things the present “anti-torture president” is just too “legalistic” to do. Barack Obama may well assert that “the facts don’t bear him out,” but as long as the “details of it” cannot be revealed “without violating classification,” as long as secrecy can be wielded as the dark and potent weapon it remains, Cheney’s politics of torture will remain a powerful if half-submerged counter-story, waiting for the next attack to spark it into vibrant life.

2.

“Key to what we did” in the “War on Terror,” the former vice-president told CNN, “was to collect intelligence against the enemy. That’s what…the enhanced interrogation program was all about.” It was not about punishment or pain or degradation but rather about intelligence. The question was, how to gather vital intelligence most efficiently and yet do it—as the former vice-president insists it was done—“legally” and “in accordance with our constitutional practices and principles.” These “techniques” would not be torture but rather “enhanced interrogation” or “extreme interrogation,” or, in President George W. Bush’s favored phrase, almost beautiful in its utter and perfect neutrality, “an alternative set of procedures.” These “procedures” were “designed to be safe, to comply with our laws, our Constitution, and our treaty obligations.”6

Working through the forty-three pages of the International Committee of the Red Cross’s report, one finds a strikingly detailed account of horrors inflicted on fourteen “high-value detainees” over a period of weeks and months—horrors that Red Cross officials conclude, quite unequivocally, “constituted torture.” It is hard not to reflect how officials concerned about protecting the country arrived at this particular “alternative set of procedures,” and how they convinced themselves, with the help of attorneys in the White House and in the Department of Justice, that these “procedures” were legal. Thanks especially to pathbreaking reporting by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, to the historical work of Alfred W. McCoy, and now to a partially released report by the Senate Armed Services Committee and a series of leaked and declassified memos by the Bush Justice Department, we have a fairly extensive record of the intricate bureaucratic mechanics of how the program came to be. We can find its roots in various CIA studies of sensory deprivation and induced psychosis and “learned helplessness,” some of them more than four decades old, and, in the case of the particular “alternative set of procedures,” in the work of consultants and psychologists who had been involved in shaping and administering the SERE (“Survival Evasion Resistance and Escape”) “counter-resistance” program developed by the US military.7

The effort began early in the days after the September 11 attacks. By December 2001, according to the Senate Armed Services Committee report, the general counsel in the Department of Defense “had already solicited information on detainee ‘exploitation’ from the Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA), an agency whose expertise was in training American personnel to withstand interrogation techniques considered illegal under the Geneva Conventions.” Two months later, on February 7, 2002, President Bush signed a memorandum stating that the Third Geneva Convention in effect didn’t apply to prisoners in the “War on Terror.” This decision cleared the way for the adaptation of SERE techniques to interrogation of prisoners in the “War on Terror.” As the authors of the Senate Armed Services Committee report explain:

During the resistance phase of SERE training, US military personnel are exposed to physical and psychological pressures…designed to simulate conditions to which they might be subject if taken prisoner by enemies that did not abide by the Geneva Conventions. As one JPRA instructor explained, SERE training is “based on illegal exploitation (under the rules listed in the 1949 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War) of prisoners over the last 50 years.”

The techniques used in SERE school, based, in part, on Chinese Communist techniques used during the Korean war to elicit false confessions, include stripping students of their clothing, placing them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads, disrupting their sleep, treating them like animals, subjecting them to loud music and flashing lights, and exposing them to extreme temperatures. It can also include face and body slaps and until recently, for some who attended the Navy’s SERE school, it included waterboarding.8

An awareness of this history makes reading the International Committee of the Red Cross report a strange exercise in climbing back through the looking glass. For in interviewing the fourteen “high-value detainees,” who had been imprisoned secretly in the “black sites” anywhere from “16 months to almost four and a half years,” the Red Cross experts were listening to descriptions of techniques applied to them that had been originally designed to be illegal “under the rules listed in the 1949 Geneva Conventions.” And then the Red Cross investigators, as members of the body designated by the Geneva Conventions to supervise treatment of prisoners of war and to judge that treatment’s legality, were called on to pronounce whether or not the techniques conformed to the conventions in the first place. In this judgment, they are, not surprisingly, unequivocal:

The allegations of ill-treatment of the detainees indicate that, in many cases, the ill-treatment to which they were subjected while held in the CIA program, either singly or in combination, constituted torture. In addition, many other elements of the ill-treatment, either singly or in combination, constituted cruel and inhuman or degrading treatment.

In view of the roots of the “alternative set of procedures,” this stark judgment might be dismissed as the chronicle of a verdict foretold. Both “torture” and “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” are declared illegal under the Third Geneva Convention, to which the Supreme Court ruled in June 2006 that—President Bush’s February 2002 memorandum notwithstanding—the United States in its treatment of all prisoners must adhere. They are also illegal under the Convention Against Torture of 1984, to which the United States is a signatory, and illegal under the War Crimes Act of 1996 (though the Military Commissions Act of 2006 makes an attempt to shield those who applied the “alternative set of procedures” from legal consequences under this law). What is more, as the report concludes,

The totality of the circumstances in which the fourteen were held effectively amounted to an arbitrary deprivation of liberty and enforced disappearance, in contravention of international law.

It is a testament as much to the peculiarities of the American press—to its “stenographic function” and its institutional unwillingness to report as fact anything disputed, however implausibly, by a high official—that the former vice-president’s insistence that these interrogations were undertaken “legally” and “in accordance with our constitutional practices and principles” continues to be reported without contradiction, and that President Bush’s oft-repeated assertion that “the United States does not torture” is still respectfully quoted and, in many quarters, taken seriously. That they are so reported is a political fact, and a powerful one. It makes it possible to contend that, however adamant the arguments of the lawyers “on either side,” the very fact of their disagreement makes the legality of these procedures a matter of partisan political allegiance, not of law.

3.

In the long months of confinement, I often thought of how to transmit the pain that a tortured person undergoes. And always I concluded that it was impossible.

—Jacobo Timerman9

Whatever the tangled history of the techniques described in the ICRC report—whatever the sources in Communist China or Soviet Russia or wherever else they might be traced—what was done in the end was quite simple. In setting out after September 11 to “do whatever it takes” in the “tough, mean, dirty, nasty business” of protecting the country against “evil people,” Bush administration officials were modern people treading a timeless road. However impressive the advanced degrees of the consultants they hired, the techniques of “enhanced interrogation” are in their essence ancient, for they play on emotions and physical realities that are basic and unchanging. Consider, for example, the “crude but effective” methods of the Soviet State Political Directorate (GPU):

They consisted usually of tying the victim in a strait-jacket to an iron bunk. The strait-jacket was his only clothing; he had no blanket, no food and was unable to go to the lavatory. With a gag in his mouth and a stopper in his rectum he would be given periodic beatings with rubber poles.10

Brutal stuff; hard to imagine Americans, however intent on “collecting intelligence against the enemy,” engaging in such things. And yet as one looks again at those “crude but effective” procedures, one notices certain unchanging necessities. There is, for example, the basic need to keep the subject helpless and restrained, here accomplished with forced nudity and a straitjacket. In the “black sites,” the same end was achieved by forced nudity and what the Red Cross terms, in its chapter of the same name, “prolonged use of handcuffs and shackles.” One of the fourteen detainees, for example, tells the Red Cross investigators that

he was kept for four and a half months continuously handcuffed and seven months with the ankles continuously shackled while detained in Kabul in 2003/4. On two occasions, his shackles had to be cut off his ankles as the locking mechanism had ceased to function, allegedly due to rust.

This technique, like other of the “alternative set of procedures” detailed by the Red Cross, seems to have been consistently applied to many of the fourteen “high-value” detainees. Walid bin Attash told the Red Cross investigators that

he was kept permanently handcuffed and shackled throughout his first six months of detention. During the four months he was held in his third place of detention, when not kept in the prolonged stress standing position [with his hands shackled to the ceiling], his ankle shackles were allegedly kept attached by a one meter long chain to a pin fixed in the corner of the room where he was held.

As with the GPU set of procedures, prisoners were kept naked, deprived of blankets, mattresses, and other necessities, and deprived of food. As for “the stopper in the rectum,” it was supplied by the GPU to deal with the practical if unpleasant problem of how to cope, in the case of a person who is naked and entirely under restraint and at the same time experiencing prolonged and extreme pain, with the inevitable consequences of his bodily functions. The Americans at the “black sites,” who had also to face this unpleasant necessity, particularly when holding detainees in “stress positions,” for example, forcing them for many days to stand naked with their hands shackled to a bolt in the ceiling and their ankles shackled to a bolt in the floor, developed their own equivalent:

While being held in this position some of the detainees were allowed to defecate in a bucket. A guard would come to release their hands from the bar or hook in the ceiling so that they could sit on the bucket. None of them, however, were allowed to clean themselves afterwards. Others were made to wear a garment that resembled a diaper. This was the case for Mr. Bin Attash in his fourth place of detention. However, he commented that on several occasions the diaper was not replaced so he had to urinate and defecate on himself while shackled in the prolonged stress standing position. Indeed, in addition to Mr. Bin Attash, three other detainees specified that they had to defecate and urinate on themselves and remain standing in their own bodily fluids.

One turns, finally, to those “periodic beatings with rubber poles” that the GPU administered. No rubber poles are to be found in the Red Cross report. Once again, though, as with the stopper in the rectum and the diapers, the rubber poles simply represent the GPU’s practical solution to a problem shared by the CIA at the “black sites”: How can one beat a detainee repeatedly without causing debilitating or permanent injury that might make him unfit for further interrogation? How, that is, to get the pain and its effect while minimizing the physical consequences?

Where the GPU responded by developing rubber poles, the CIA created its plastic collar, “an improvised thick collar or neck roll,” as the Red Cross investigators describe it in Chapter 1.3.3 (“Beating by use of a collar”), that “was placed around their necks and used by their interrogators to slam them against the walls.” Though six of the fourteen detainees report the use of the “thick plastic collar,” which, according to Khaled Shaik Mohammed, would then be “held at the two ends by a guard who would use it to slam me repeatedly against the wall,” it is plain that this particular technique was perfected through experimentation. Indeed, the plastic collar seems to have begun as a rather simple mechanism: an everyday towel that was looped around the neck, the ends gathered in the guard’s fist. The collar appeared later and brought with it other innovations:

Mr. Abu Zubaydah commented that when the collar was first used on him in his third place of detention, he was slammed directly against a hard concrete wall. He was then placed in a tall box for several hours (see Section 1.3.5, Confinement in boxes). After he was taken out of the box he noticed that a sheet of plywood had been placed against the wall. The collar was then used to slam him against the plywood sheet. He thought that the plywood was in order to absorb some of the impact so as to avoid the risk of physical injury.

How to inflict pain without causing injury that might inhibit or prevent further interrogation? And how to do so in such a way that the pain inflicted might be said not to be akin to that “associated with serious physical injury so severe that death, organ failure, or permanent damage resulting in a loss of significant body function will likely result”? This was of course the legal definition of torture concocted by White House and Justice Department lawyers (and codified in what has come to be known as the “Torture Memo,” written by John Yoo and signed by Jay Bybee on August 1, 2002). The challenging task set before these lawyers was to somehow “make legal” a set of techniques that had originated in a program developed expressly to prepare soldiers for techniques that were illegal, and thereby to offer officials and interrogators a “golden shield” that would suffice to convince them they would be protected from legal consequences.)

In answer to these questions, and with the benefit of experimentation, especially on Mr. Abu Zubaydah, one of the first of the alleged “big fish” al-Qaeda captives, the CIA seems to have arrived at a method that is codified by the International Committee of the Red Cross experts into twelve basic techniques, as follows:

- Suffocation by water poured over a cloth placed over the nose and mouth…

- Prolonged stress standing position, naked, held with the arms extended and chained above the head…

- Beatings by use of a collar held around the detainees’ neck and used to forcefully bang the head and body against the wall…

- Beating and kicking, including slapping, punching, kicking to the body and face…

- Confinement in a box to severely restrict movement…

- Prolonged nudity…this enforced nudity lasted for periods ranging from several weeks to several months…

- Sleep deprivation…through use of forced stress positions (standing or sitting), cold water and use of repetitive loud noises or music…

- Exposure to cold temperature…especially via cold cells and interrogation rooms, and…use of cold water poured over the body or…held around the body by means of a plastic sheet to create an immersion bath with just the head out of water.

- Prolonged shackling of hands and/or feet…

- Threats of ill-treatment, to the detainee and/or his family…

- Forced shaving of the head and beard…

- Deprivation/restricted provision of solid food from 3 days to 1 month after arrest…

As the Red Cross writers tell us, “each specific method was in fact applied in combination with other methods, either simultaneously or in succession.” A clear picture of this cumulative effect comes from the three long excerpts of interviews with detainees published as annexes at the end of the report, which I have quoted from and discussed at length in my earlier article.11 To understand the effect one must remember what all experienced torturers know: dramatic results can be achieved with simple techniques. Forced standing, for example:

Ten of the fourteen alleged that they were subjected to prolonged stress standing positions, during which their wrists were shackled to a bar or hook in the ceiling above the head for periods ranging from two or three days continuously, and for up to two or three months intermittently…. For example, Mr. Khaled Shaik Mohammed alleged that, apart from the time when he was taken for interrogation, he was shackled in prolonged stress standing position for one month in his third place of detention…. Mr. Bin Attash for two weeks with two or three short breaks where he could lie down in Afghanistan and for several days in his fourth place of detention…. Mr. Hambali for four to five days, blindfolded with a type of sack over his head, while still detained in Thailand….

This prolonged forced standing is, again, an ancient technique, and a favorite, notably, of the Soviet intelligence services. It can be difficult, when gazing at the stark descriptions of these procedures, to understand their effect. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, for example, when approving in December 2002 a series of interrogation techniques that included forced standing for up to four hours, famously scribbled in the lower margin, beneath his initials: “However, I stand for 8–10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours? D.R.” Secretary Rumsfeld, who no doubt was standing at his desk when he scrawled these words, professed to have difficulty comprehending the difference between working at a standing desk in one’s office—signing documents, talking on the telephone, speaking to subordinates, drinking coffee—and standing naked in a very cold room with hands shackled to the ceiling for hours and days at a time.

One can gain a hint of the difference simply by rising and standing motionless with one’s hands extended directly overhead and trying to maintain the position for, say, thirty minutes. Then imagine maintaining it for several hours, or days, or weeks. The physical effects, as described in a notorious study of Communist interrogation methods by two psychologists, are dramatic:

After 18 to 24 hours of continuous standing, there is an accumulation of fluid in the tissues of the legs. This dependent edema is produced by the extravasation of fluid from the blood vessels. The ankles and feet of the prisoner swell to twice their normal circumference. The edema may rise up the legs as high as the middle of the thighs. The skin becomes tense and intensely painful. Large blisters develop, which break and exude watery serum….12

This medical observation is confirmed in the accounts of at least two of the detainees in the ICRC report, including that of Khaled Shaik Mohammed:

…I was kept for one month in the cell in a standing position with my hands cuffed and shackled above my head and my feet cuffed and shackled to a point in the floor. Of course during this month I fell asleep on some occasions while still being held in this position. This resulted in all my weight being applied to the handcuffs around my wrists resulting in open and bleeding wounds…. [Scars consistent with this allegation were visible on both wrists as well as both ankles.] Both my feet became very swollen after one month of almost continual standing.13

4.

I fundamentally disagree with Dick Cheney…. The facts don’t bear him out.

—President Barack Obama, 60 Minutes, March 22, 2009

One fact, seemingly incontrovertible, after the descriptions contained and the judgments made in the ICRC report, is that officials of the United States, in interrogating prisoners in the “War on Terror,” have tortured and done so systematically. From many other sources, including the former president himself, we know that the decision to do so was taken at the highest level of the American government and carried out with the full knowledge and support of its most senior officials.

Once this is accepted as a fact, certain consequences might be expected to follow. First, that these policies, violating as they do domestic and international law, must be changed—which, as noted, President Obama began to accomplish on his first full day in office. Second, that they should be explicitly repudiated—a more complicated political process, which has, perhaps, begun, but only begun. Third, that those who ordered, designed, and applied them must be brought before the public in some societally sanctioned proceeding, made to explain what they did and how, and suffer some appropriate consequence.

And fourth, and crucially, that some judgment must be made, based on the most credible of information compiled and analyzed and weighed by the most credible of bodies, about what these policies actually accomplished: how they advanced the interests of the country, if indeed they did advance them, and how they hurt them. For at this point, President Obama’s assertion that “the facts don’t bear [Cheney] out” remains simply that: an assertion. To that assertion Mr. Cheney and others, including President Bush, respond and will continue to respond with claims of “specific attacks that were stopped by virtue of what we learned through these programs”—about which, of course, they “can’t give you details…without violating classification.” And when public officials do cite specific cases—as President Bush himself did in describing the use of the “alternative set of procedures” on Abu Zubaydah, who, the President claimed, “was a senior terrorist leader” who “provided information that helped stop a terrorist attack being planned for inside the United States”—other officials, many of them also “in a position to know,” leak differing versions to reporters which seem to demonstrate that the claims that were made are exaggerations and worse.14

Unfortunately, these contrary accounts, however convincing—and in the case of Abu Zubaydah they have been very convincing—generally come from unnamed officials and cannot serve as definitive proof, or as a sufficiently credible repudiation of what former officials, including the President of the United States, still assert. Far from ending the discussion about whether torture really was, as Cheney insists, “absolutely crucial to getting us through the last seven-plus years without a major-casualty attack,” these ongoing battles between extravagant claims and undermining leaks will ensure that it persists.

It is because of the claim that torture protected the US that the many Americans who still nod their heads when they hear Dick Cheney’s claims about the necessity for “tough, mean, dirty, nasty” tactics in the war on terror respond to its revelation not by instantly condemning it but instead by asking further questions. For example: Was it necessary? And: Did it work? To these questions the last president and vice-president, who “kept the country safe” for “seven-plus years,” respond “yes,” and “yes.” And though as time passes the numbers of those insisting on asking those questions, and willing to accept those answers, no doubt falls, it remains significant, and would likely grow substantially after another successful attack.

This political fact partly explains why, when it comes to torture, we seem to be a society trapped in a familiar and never-ending drama. For though some of the details provided—and officially confirmed for the first time—in the ICRC report are new, and though the first-person accounts make chilling reading and have undoubted dramatic power, one can’t help observing that the broader discussion of torture is by now in its essential outlines nearly five years old, and has become, in its predictably reenacted outrage and defiant denials from various parties, something like a shadow play.15

News of the “black sites” first appeared prominently in the press—on the front page of TheWashington Post

—in December 2002.16 A year and a half later, after the publication and broadcast of the Abu Ghraib photographs—the one moment in the last half-dozen years when the torture story, thanks to the lurid images, became “televisual”—a great wave of leaks swept into public view hundreds of pages of “secret” documents about torture and the Bush administration’s decision-making regarding it.17 There have been many important “revelations” since, but none of them has changed the essential fact: by no later than the summer of 2004, the American people had before them the basic narrative of how the elected and appointed officials of their government decided to torture prisoners and how they went about it.

The reports on American torture now fill a shelf next to my desk, beginning with the Taguba Report in 2004, still perhaps the best of them, and then going on to include the ICRC report on Abu Ghraib, the Schlesinger Report, the Fay/Jones Report, the Church Report, the Schmidt Report, and now the Armed Services Committee Report, the full text of which will soon break into the news in all its glory, telling us in much more conclusive detail a story the major outlines of which we already know. More revelations will come from this, and more news, particularly about the mechanics by which prominent senior officials approved use of the “alternative set of procedures” and closely monitored their day-to-day application. We will continue in an endless round-robin of revelation, in which we tell ourselves we are learning something new though in fact, when it comes to the central problem of torture—what we as a society should do about it and whether we will in fact do anything—we are in the end simply repeating to ourselves things, however increasingly detailed and awful, that we already know.

Meantime a number of organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union in a powerful letter by its director, Anthony Romero, have called on Attorney General Eric Holder—who in his confirmation hearings said bluntly that “waterboarding is torture”—to appoint a special prosecutor to look into possible violations of the law under the Bush administration’s interrogation program. As I write, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Patrick Leahy of Vermont, has called for the establishment of a kind of “truth commission” that will gather information, in part by trading immunity from prosecution for former officials for their truthful testimony, about “how our detention policies and practices…have seriously eroded fundamental American principles of the rule of law.” And the chair of the Intelligence Committee, Senator Dianne Feinstein of California, and its ranking member, Senator Christopher Bond of Missouri, have announced their own investigation into “how the CIA created, operated, and maintained its detention and interrogation program” and—what is crucial—their intention to make “an evaluation of intelligence information gained through the use of enhanced and standard interrogation techniques.”

5.

That is the central, unanswered question: What was gained? We know already a good deal about what was lost. On this subject President Obama in his 60 Minutes response was typically eloquent:

I mean, the fact of the matter is after all these years how many convictions actually came out of Guantánamo? How many terrorists have actually been brought to justice under the philosophy that is being promoted by Vice President Cheney? It hasn’t made us safer. What it has been is a great advertisement for anti-American sentiment. Which means that there is constant effective recruitment of Arab fighters and Muslim fighters against US interests all around the world…. The whole premise of Guantánamo promoted by Vice President Cheney was that somehow the American system of justice was not up to the task of dealing with these terrorists…. Are we going to just keep on going until the entire Muslim world and Arab world despises us? Do we think that’s really going to make us safer?

This is as clear and concise a summary of the damage wrought by torture as one is likely to get. Torture has undermined the United States’ reputation for respecting and following the law and thus has crippled its political influence. By torturing, the United States has wounded itself and helped its enemies in what is in the end an inherently political war—a war, that is, in which the critical target to be conquered is the allegiances and attitudes of young Muslims. And by torturing prisoners, many of whom were implicated in committing great crimes against Americans, the United States has made it impossible to render justice on those criminals, instead sentencing them—and the country itself—to an endless limbo of injustice. That limbo stands as a kind of worldwide advertisement for the costs of the US reversion to torture, whose power President Obama has tried to reduce by announcing that he will close Guantánamo.

The question is how to set beside this damage to the country’s interests—some of which can be measured by polling data in Muslim countries, by rises in recruitment to violent jihadist groups, and so on—against the claims that attacks have been averted. As is so often the case, the categories are not commensurable. Confronted with former Vice President Cheney’s arguments, President Obama says “the facts don’t bear him out,” but the facts he points to appear to be facts about the political damage caused by torture, or about the difficulties it poses to the country in trying to prosecute prisoners. He appears not to be speaking about the same facts that the former administration officials do—facts that they claim prove that torture, in averting attacks and protecting the country, saved lives.

Investigating what kind of intelligence torture actually yielded is not a popular task: those who oppose torture do not like to admit that it might, in any way, have “worked”; those who support its use don’t like to admit that it might not have. It is a regrettable but undeniable fact that torture’s illegality, or the political harm it may do to the country’s reputation, is not sufficient to discourage the willingness of many Americans to countenance it. However one might prefer that this be an argument about legality or morality, it is also an argument about national security and, in the end, about politics. However much one agrees with President Obama that Cheney’s “notion” that “somehow…we can’t reconcile our core values, our Constitution, our belief that we don’t torture, with our national security interests,” the fact is that many people continue to believe the contrary, and this group includes the former president and vice-president of the United States and many senior officials who served them.

There is a reason that the myth of the “ticking bomb” and the daring, ruthless US agent who will do anything to stop its detonation—anything including torture, a step that proves his commitment and his seriousness—is sacralized in popular culture, and not only in television dramas like 24 but in Dirty Harry and the other movies that are its ancestors. The story of the ticking bomb and the torturing hero who defuses it offers a calming message to combat pervasive anxiety and fear—that no matter what horrible threats loom, there are those who will make use of untrammeled government power to protect the country. It also appeals to uglier and equally powerful emotions: the desire for retribution, the urge to punish and to avenge, the felt need in the face of vulnerability to assert power.18

In this political calculus, liberals obsessed by “legalisms” are part of the problem, not part of the solution, and it is no accident that it is firmly in that camp that the former vice-president has been seeking to isolate the new president. Cheney’s success in this endeavor will not be evident now—he is, after all, the most unpopular member of a deeply unpopular party—but the seeds he is so ostentatiously sowing could, if unchallenged by facts and given the right conditions, flourish dramatically in the future.

The only way to defuse the political volatility of torture and to remove it from the center of the “politics of fear” is to replace its lingering mystique, owed mostly to secrecy, with authoritative and convincing information about how it was really used and what it really achieved. That this has not yet happened is the reason why, despite the innumerable reports and studies and revelations that have given us a rich and vivid picture of the Bush administration’s policies of torture, we as a society have barely advanced along this path. We have not so far managed, despite all the investigations, to produce a bipartisan, broadly credible, and politically decisive effort, and pronounce authoritatively on whether or not these activities accomplished anything at all in their stated and still asserted purpose: to protect the security interests of the country.

This cannot be accomplished through the press; for the same institutional limitations that lead journalists to keep repeating Bush and Cheney’s insistence about the “legality” of torture make it impossible for the press alone, no matter how persuasive the leaks it brings to the public, to make a politically decisive judgment on the value of torture. What is lacking is not information or revelation but political credibility. What is needed is not more disclosures but a broadly persuasive judgment, delivered by people who can look at all the evidence, however highly classified, and can claim bipartisan respect on the order of the Watergate Select Committee or the 9/11 Commission, on whether or not torture made Americans safer.

This is the only way we can begin to come to a true consensus about torture. By all accounts, it is likely that the intelligence harvest that can be attributed directly to the “alternative set of procedures” is meager. But whatever information might have been gained, it must be assessed and then judged against the great costs, legal, moral, political, incurred in producing it. Torture’s harvest, whatever it may truly be, is very unlikely to have outweighed those costs.

6.

Such an investigation would have to begin with an inquiry into the broader issue of the Bush administration’s detention policies after September 11. These policies, built on a cascading series of reverse incentives, filled United States facilities, from Guantánamo to Abu Ghraib to the secret prisons, with tens of thousands of prisoners.

The reverse incentives began with the bounties of anywhere from several hundred to thousands of dollars offered by US Special Forces in Afghanistan for any “Al Qaeda or Taliban member” whom Afghans might bring to American soldiers—incentives that led to the imprisonment of hundreds of Afghan farmers and even of lower-level Taliban who offered nothing whatever in the form of intelligence but who nonetheless ended up imprisoned in Guantánamo, often for years. They were sent there by young US Army interrogators, many of them reservists with little training and no language skills, who found themselves with the awful responsibility of deciding whether or not to let these prisoners go—and who, whatever their doubts about the prisoners’ value as intelligence sources, in the days after September 11 had no practical incentive to release them and every incentive not to. As Chris Mackey, the pseudonym of an Army reservist who served as an interrogator in Afghanistan in 2002, said:

In talking to some of the officers at Kandahar and Bagram…they all talk about how there was a great fear among them, those who were going to be putting their signatures to the release of prisoners, great fear that they were going to somehow manage to release somebody who would later turn out to be the 20th hijacker. So there was real concern and a real erring on the conservative side, especially early in the war.19

This pervasive and understandable concern, together with a lack of competent linguists and interrogators in the combat zone, led to a general policy of rounding up suspects that flooded Guantánamo with prisoners who simply should not have been there. Lawrence Wilkerson, a retired US Army colonel who at the time served as chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, confirms what other studies have shown: that because of “the utter incompetence of the battlefield vetting in Afghanistan” and “the incredible pressure coming down from Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld and others to ‘just get the bastards to the interrogators,'” many or even most of those detained “were innocent of any substantial wrongdoing, had little intelligence value, and should be immediately released.” Colonel Wilkerson goes on:

Several in the US leadership became aware of this improper vetting very early on…. But to have admitted this reality would have been a black mark on their leadership from virtually day one of the so-called Global War on Terror and these leaders already had black marks enough: the dead in a field in Pennsylvania, in the ashes of the Pentagon, and in the ruins of the World Trade Towers. They were not about to admit to their further errors at Guantánamo Bay. Better to claim that everyone there was a hardcore terrorist, was of enduring intelligence value, and would return to jihad if released.20

These initial errors, and the adamant refusal to correct or admit them, led to an overwhelmed, inefficient, and fundamentally unjust US detention system, one that displayed for the world, in televised images of orange-suited, shackled, and hooded prisoners at Guantánamo, and later naked, grotesquely contorted, and abused prisoners at Abu Ghraib, a kind of continuing lurid recruitment poster for al-Qaeda—a dramatic visual confirmation and reaffirmation of the very claims of an evil, repressive, imperialistic United States that lay at the heart of its ideology. Many studies have confirmed the essential truth that a great many prisoners, probably a majority, were unjustly held, without adequate cause or sufficient investigation.21 Of the nearly eight hundred prisoners who have passed through Guantánamo, well over half have been released without charge, often after years of detention.

The initial panicked rush to “round up prisoners,” which was replicated in Iraq during the first months of the insurgency in the summer and fall of 2003, led to what Wilkerson calls an “ad hoc intelligence philosophy” developed to “justify keeping many of these people, called the mosaic philosophy.”

Simply stated, this philosophy held that it did not matter if a detainee were innocent. Indeed, because he lived in Afghanistan and was captured on or near the battle area, he must know something of importance…. All that was necessary was to extract everything possible from him and others like him, assemble it all in a computer program, and then look for cross-connections and serendipitous incidentals—in short, to have sufficient information about a village, a region, or a group of individuals, that dots could be connected and terrorists or their plots could be identified.

Thus, as many people as possible had to be kept in detention for as long as possible to allow this philosophy of intelligence gathering to work. The detainees’ innocence was inconsequential.

I saw the consequences of this policy in Iraq, in the fall of 2003, when “neighborhood sweeps” and “cordon and capture operations” in “hot areas” led to wholesale arrests of young men. These men, about whom nothing was known apart from the fact that they were young and lived in a neighborhood deemed “hot,” were flex-cuffed, hooded, and promptly sent to Abu Ghraib, where they…sat. Interrogators were overwhelmed, mostly with prisoners who simply had no intelligence to impart. The interrogators were well aware of this, of course, but in part because officers of the combat units who made the arrests sat on the boards that had to approve prisoner releases, it was almost impossible to release prisoners once they had been brought to Abu Ghraib. “Certain [Coalition Forces] military intelligence officers told the ICRC,” according to a 2004 Red Cross report on Abu Ghraib, “that in their estimate between 70 percent and 90 percent of the persons deprived of their liberty in Iraq had been arrested by mistake.”22

As military interrogators described to me in some detail, these numbers overwhelmed the intelligence collection system that the wholesale arrests were intended to supply and fortify, leading interrogators to spend most of their time working through thousands of prisoners who had nothing to tell them—but who nonetheless could in most cases not be released and had to be interviewed, often repeatedly.

One soon begins to see a pattern: among officials at the top, panic and fear and incompetence lead to a compensating, self-justifying desire to “do whatever’s necessary” to prevent attacks and finally to a consequent injustice inflicted on the innocents at the bottom that is both persistent and politically damaging. Thus the movement from Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld’s call to “just get the bastards to the interrogators” to the overflow of innocent prisoners from Guantánamo to Abu Ghraib, innocents who rendered unworkable the very system that the “get tough” directives were meant to snap into effective action.

Chris Mackey, the US Army interrogator, writes of “the gravitational laws that govern human behavior when one group of people is given complete control over another in a prison. Every impulse tugs downward.”23 All evidence suggests that in the days after September 11, 2001, the very officials who should have been ensuring that there were restraints put on such “gravitational laws” were instead doing all they could to augment them. Fear and a compensating desire to prove that nothing would be allowed to stand in the way of the all-important goal of protecting the country—especially not overly “legalistic” notions about international treaties and limitations on presidential power—were allowed to drive policy, and the country is still struggling to cope with the results.

7.

We know a great deal about the Bush administration’s policy of torture but we need to know more. We need to know, from an investigation that will study all the evidence, classified at however high a level of secrecy, and that will speak to the nation with a credible bipartisan voice, whether the use of torture really did produce information that, in the words of the former vice-president, was “absolutely crucial to getting us through the last seven-plus years without a major-casualty attack on the US.” We already have substantial reason to doubt these claims, for example the words of Lawrence Wilkerson, who, as chief of staff to Secretary of State Powell, had access to intelligence of the highest classification:

It has never come to my attention in any persuasive way—from classified information or otherwise—that any intelligence of significance was gained from any of the detainees at Guantánamo Bay other than from the handful of undisputed ring leaders and their companions, clearly no more than a dozen or two of the detainees, and even their alleged contribution of hard, actionable intelligence is intensely disputed in the relevant communities such as intelligence and law enforcement.

It is important to note that a great many of those charged with the duty to “keep us safe” do not share the former president’s view about the necessity of his “alternative set of procedures.” Indeed, on September 6, 2006, a couple of hours before President Bush told the nation in his East Room speech about the “separate program operated by the Central Intelligence Agency” where the “alternative set of procedures” were used, and announced that the fourteen “suspected terrorist leaders and operatives” were being sent from the black sites to Guantánamo (where they would tell their stories at last to the Red Cross investigators), a very different event was taking place across the Potomac. At the Department of Defense, high-ranking officers and officials were introducing the new Army Field Manual for Human Intelligence Collector Operations— the newly rewritten manual for interrogators that was, as Lieutenant General John Kimmons, the Army deputy chief of staff for intelligence, pointed out, unique in a number of ways:

The Field Manual explicitly prohibits torture or cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment or punishment…. To make this more imaginable and understandable to our soldiers…we have included in the Field Manual specific prohibitions. There’s eight of them: interrogators may not force a detainee to be naked, perform sexual acts or pose in a sexual manner; they cannot use hoods or place sacks over a detainee’s head or use duct tape over his eyes; they cannot beat or electrically shock or burn them or inflict other forms of physical pain—any form of physical pain; they may not use water boarding, they may not use hypothermia or treatment which will lead to heat injury; they will not perform mock executions; they may not deprive detainees of the necessary food, water and medical care; and they may not use dogs in any aspect of interrogations….24

Lieutenant General Kimmons’s list of procedures is remarkable for including almost all of those that had come to light during the years of the Bush administration, either at Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo, or, now, at the “black sites.” Indeed, just before his commander in chief’s vivid defense to the country of the necessity of the “alternative set of procedures,” the general was declaring that the military had expressly forbidden precisely those procedures—and was explaining, in answer to a reporter’s question about whether the prohibitions didn’t “limit the ability of interrogators to get information that could be very useful,” precisely why:

I am absolutely convinced the answer to your first question is no. No good intelligence is going to come from abusive practices. I think history tells us that. I think the empirical evidence of the last five years, hard years, tells us that.

And moreover, any piece of intelligence which is obtained under duress, through the use of abusive techniques would be of questionable credibility. And additionally, it would do more harm than good when it inevitably became known that abusive practices were used. And we can’t afford to go there.

And yet the “loud rhetoric” of Dick Cheney, as Colonel Wilkerson remarks, “continues even now” and remains a persistent political fact in our debate about national security. What should be a debate about facts remains instead a debate fueled by reckless assertions about “still classified” intelligence and leaks that undermine those assertions. The debate over the supposed importance of intelligence provided by Abu Zubaydah, whose torture, including waterboarding, is related with awful immediacy in the ICRC report, is only the most prominent of these controversies. Though waterboarding has not been performed on prisoners in American custody since 2003, there is a reason we continue to talk about it. Though we have known about the Bush administration’s policy of torture for five years, there is unquestionably more debate about it now than there ever has been. We are having, in a ragged way, the debate about ethics and morality in our national security policies that we never had in the days after September 11, when decisions were made in secret by a handful of officials.

Philip Zelikow, who served the Bush administration in the National Security Council and the State Department and then went on to direct the 9/11 Commission, remarked in an important speech three years ago that these officials, instead of having that debate simply called in the lawyers: the focus, that is, was not on “what should we do” but on “what can we do.”25

There is a sense in which our society is finally posing that “what should we do” question. That it is doing so only now, after the fact, is a tragedy for the country—and becomes even more damaging as the debate is carried on largely by means of politically driven assertions and leaks. For even as the practice of torture by Americans has withered and died, its potency as a political issue has grown. The issue could not be more important, for it cuts to the basic question of who we are as Americans, and whether our laws and ideals truly guide us in our actions or serve, instead, as a kind of national decoration to be discarded in times of danger. The only way to confront the political power of the issue, and prevent the reappearance of the practice itself, is to take a hard look at the true “empirical evidence of the last five years, hard years,” and speak out, clearly and credibly, about what that story really tells.

—April 2, 2009; this is the second of two articles.

This Issue

April 30, 2009

-

1

See John F. Harris, Mike Allen, and Jim VandeHei, “Cheney Warns of New Attacks,” Politico, February 4, 2009. ↩

-

2

See my article, “US Torture: Voices from the Black Sites,” The New York Review, April 9, 2009, in which the ICRC report is extensively excerpted, and to which the present essay is a sequel. The report is based on extensive interviews, carried out in October and December 2006, with fourteen so-called “high-value detainees,” who had been imprisoned and interrogated for extended periods at the “black sites,” a series of secret prisons operated by the CIA in a number of countries around the world, including, at various times, Thailand, Afghanistan, Poland, Romania, and Morocco. Download the full text of the report. ↩

-

3

Among others, the Senate Armed Services Committee has made public parts of its Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in US Custody and more of this will doubtless be released in coming days. Meanwhile, a Spanish judge sent to a prosecutor a case against Alberto Gonzales, the former White House counsel and attorney general, and five other senior Bush officials, including John Yoo and Jay Bybee. See Marlise Simons, “Spanish Court Weighs Inquiry on Torture for 6 Bush-Era Officials,” The New York Times, March 28, 2009. In the United Kingdom, the Crown Prosecution Service has begun an inquiry into allegations of the torture of Binyam Mohamed during his detention by the CIA. In Poland, prosecutors have reportedly begun an inquiry into allegations that the CIA made use of an abandoned military facility as a “black site” to torture prisoners. ↩

-

4

“Interview with Dick Cheney,” State of the Union With John King, CNN, March 15, 2009. ↩

-

5

See “Obama on AIG Rage, Recession, Challenges,” 60 Minutes, March 22, 2009. ↩

-

6

See “President Discusses Creation of Military Commissions to Try Suspected Terrorists,” September 6, 2006, East Room, White House, available at cfr.org. This is the most important speech President Bush gave on the “alternative set of procedures” and is analyzed at length in my previous article. ↩

-

7

See, for the definitive account, Jane Mayer, “Outsourcing Torture,” The New Yorker, February 15, 2005, and The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned into a War on American Ideals (Doubleday, 2008); and also Alfred W. McCoy, A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror (Metropolitan, 2006). ↩

-

8

See Senate Armed Services Committee Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in US Custody, “Executive Summary and Conclusions,” released December 11, 2008, p. xiii. Emphasis added. ↩

-

9

See Jacobo Timerman, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number (University of Wisconsin Press, 1981), p. 32. ↩

-

10

See Robin Bruce Lockhart, Ace of Spies (1967; Penguin, 1984), p. 176. ↩

-

11

See my “US Torture: Voices from the Black Sites,” especially pp. 71–75. ↩

-

12

See Lawrence E. Hinkle Jr. and Harold G. Wolff, “Communist Interrogation and Indoctrination of ‘Enemies of the State,'” A.M.A. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, Vol. 76, No. 2 (August 1956), p. 134. ↩

-

13

The interpolated words in brackets are as they appear in the Red Cross report. ↩

-

14

I discuss the Abu Zubaydah case more fully in my previous article. Nearly three years ago author Ron Suskind offered an extensive account of Abu Zubaydah and the exaggerations that officials had made about him, from President Bush on down—both about his rank and importance in al-Qaeda and about the value of the information he supposedly offered after the application of the “alternative set of procedures.” See Ron Suskind, The One Percent Doctrine: Deep Inside America’s Pursuit of Its Enemies Since 9/11 (Simon and Schuster, 2006), especially pages 99–101 and 115–118. The debate about the case has continued to be pursued furiously in the press, an indication of the strong feelings of many, mostly unnamed officials within the intelligence and law enforcement communities. See, most recently, Peter Finn and Joby Warrick, “Detainee’s Harsh Treatment Foiled No Plots: Waterboarding, Rough Interrogation of Abu Zubaida Produced False Leads, Officials Say,” The Washington Post, March 29, 2009. ↩

-

15

Jane Mayer, in her article “The Black Sites,” The New Yorker, August 13, 2007, and in her book, The Dark Side, published many of the details of abuse contained in the ICRC report, though not texts from the report itself. ↩

-

16

See Dana Priest and Barton Gellman, “US Decries Abuse but Defends Interrogations: ‘Stress and Duress’ Tactics Used on Terrorism Suspects Held in Secret Overseas Facilities,” The Washington Post, December 26, 2002. ↩

-

17

In October of that year I published several hundred pages of those documents in my book Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib, and the War on Terror (New York Review Books, 2004). A few months later Karen J. Greenberg and Joshua L. Dratel published their more comprehensive collection, The Torture Papers: The Road to Abu Ghraib (Cambridge University Press, 2005). ↩

-

18

These emotions affect government officials as well, as this description of those who insisted on the torture of Abu Zubaydah suggests: “They couldn’t stand the idea that there wasn’t anything new,” the official said. “They’d say, ‘You aren’t working hard enough.’ There was both a disbelief in what he was saying and also a desire for retribution—a feeling that ‘He’s going to talk, and if he doesn’t talk, we’ll do whatever.'” See Finn and Warrick, “Detainee’s Harsh Treatment Foiled No Plots.” ↩

-

19

See “Interview: Chris Mackey and Greg Miller discuss their book, ‘The Interrogators,'” Fresh Air, National Public Radio, July 20, 2004. See Chris Mackey with Greg Miller, The Interrogators: Inside the Secret War Against Al Qaeda (Little, Brown, 2004). ↩

-

20

See Lawrence Wilkerson, “Some Truths About Guantánamo Bay,” The Washington Note, March 17, 2009. ↩

-

21

See, for example, Corine Hegland, “Who Is at Guantánamo Bay,” National Journal, February 3, 2006. ↩

-

22

See “Report of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on the Treatment by the Coalition Forces of Prisoners of War and Other Persons Protected by the Geneva Conventions in Iraq During Arrest, Internment and Interrogation,” February 2004, reviewed in my article “Torture and Truth,” The New York Review, June 10, 2004. ↩

-

23

See Mackey and Miller, The Interrogators, p. 471. ↩

-

24

See “DoD News Briefing with Deputy Assistant Secretary Stimson and Lt. Gen. Kimmons from the Pentagon,” September 6, 2006. ↩

-

25

See Philip Zelikow, “Legal Policy for a Twilight War,” Annual Lecture, Houston Journal of International Law, April 26, 2007. ↩