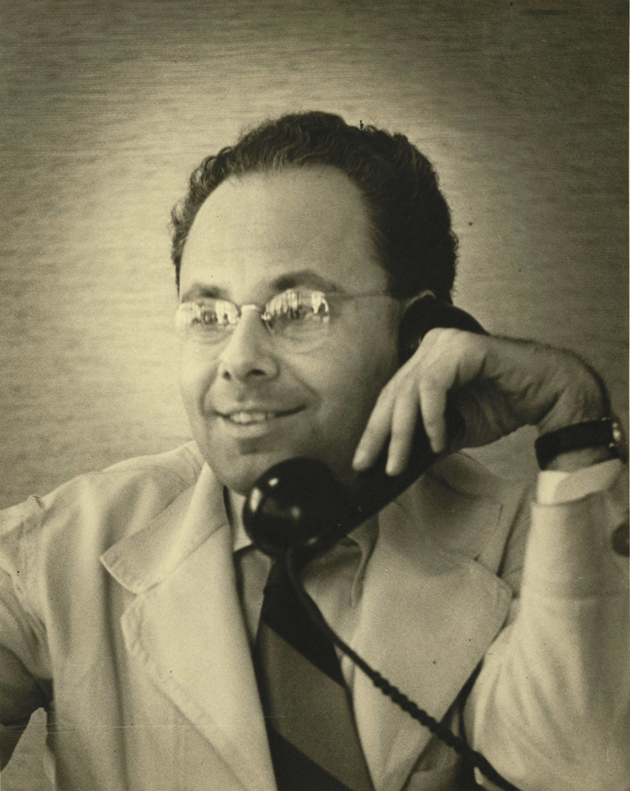

I first read Alvin Levin’s Love Is Like Park Avenue when I was about fifteen, shortly after it was published in the New Directions 1942 annual.* At the time I was beginning to explore contemporary experimental writing, thanks in part to the excellent collection at the Rochester Public Library, an art deco gem still extant on the edge of the city’s faded downtown. In fact I was searching not just for modernist writing but sexy writing as well, having already looked into Henry Miller and ignored critical warnings against combing Ulysses for the “naughty bits.” Levin’s narrative provided plenty of those, in graphic accounts of steamy sexual encounters that used such hitherto unprintable words as hard-on, cocksucker, frenching, and come (where were the censors?) in breathless run-on sentences that suggested its author too had read Molly Bloom’s soliloquy. The biographical note on Levin mentioned that the text represented about one third of a novel. I waited impatiently for New Directions to publish the complete work.

Alas, that never happened. Occasionally I would remember Love Is Like Park Avenue, and sometime in the 1990s I asked an editor at New Directions if he knew what had become of it. He replied that after searching their files he had come up with Amelia Earhart’s chinstrap, but no sign of Alvin Levin. James Laughlin, the founder of New Directions, was still alive then, but according to my informant had only vague recollections of the author. I resigned myself to the trail having grown cold. (At that time I hadn’t seen Levin’s lovely short story “Only Dreams Are True” in the 1939 annual. It could very well be a fragment of Love Is Like Park Avenue, though it stands beautifully on its own.)

A couple of years ago I thought of Levin again, and this time Barbara Epler, editor in chief at New Directions, was able to offer help. The extensive correspondence between Laughlin and Levin (mostly on Levin’s side) was found to exist in Laughlin’s archives at Harvard’s Houghton Library. At the same time a friend in Cincinnati put me in touch with James Reidel, a poet and specialist in forgotten and semi-obscure American avant-garde writers, and the author of a terrific biography of the unjustly neglected poet Weldon Kees. Reidel has now done an amazing job of tracking down more fragments of Levin’s oeuvre in little magazines and anthologies of the period, including some published by the Little Man Press in Cincinnati.

For me the search seemed to come full circle when Reidel produced a Levin story printed in a British anthology coedited by Nicholas Moore, a brilliant poet of the 1930s and 1940s whose work has fascinated me ever since I discovered it about the same time I first read Levin, again in the pages of a New Directions annual. How strange that these two forgotten icons of my youth had been in touch with each other, across the Atlantic in wartime, and that one had actually helped the other get published.

Moore has been recently reevaluated in England, and now, thanks to Reidel’s digging, readers can finally get an idea of Levin’s writing. His stream-of-consciousness narrators, often women, reflect the yearning of lower-middle-class New York Jews of the 1930s for upward mobility of the kind shown in contemporary films and cigarette ads. They dream of “Vassar girl” sweaters and men’s suits from Rogers Peet (the somewhat cheaper alternative to Brooks Brothers), of yacht clubs and supper clubs where sleek young couples dance to Glenn Miller, though they themselves have to settle for restaurant “dinners” of hot dogs and sauerkraut, and sweaty makeout sessions in parked cars. All this is conveyed in wonderfully caustic prose inflected by the cadences of radio commercials and movie “coming attractions.” The voices at their most benign anticipate Woody Allen; at their nastiest Budd Schulberg’s Sammy Glick of What Makes Sammy Run? Scabrous scenes of family feuding in the Bronx and crowded Coney Island beaches come at you with the leering verve of Reginald Marsh’s drawings and Paul Cadmus’s quasi-pornographic paintings. It’s a confused, squalid, but vehemently bubbling melting pot, where, in the author’s regretful words, “Only Dreams Are True.”

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory

-

*

This essay will appear, in slightly different form, as the preface to a new edition of Love Is Like Park Avenue, to be published by New Directions in August, with an introduction by James Reidel. ↩