1.

Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932)—who nearly called his most famous book The Wind in the Reeds —led one of those multiple lives so beloved of late Victorians: secretary of the Bank of England, contributor to the decadent Yellow Book, gently ironic celebrant of childhood in The Golden Age (1895) and Dream Days (1898). (The most famous section of the latter is the enchanting satire “The Reluctant Dragon”—about a poetry-spouting dragon and a highly civilized Saint George.) A resolute amateur of letters, Grahame refused to become a professional writer, holding himself to be “a spring not a pump.”

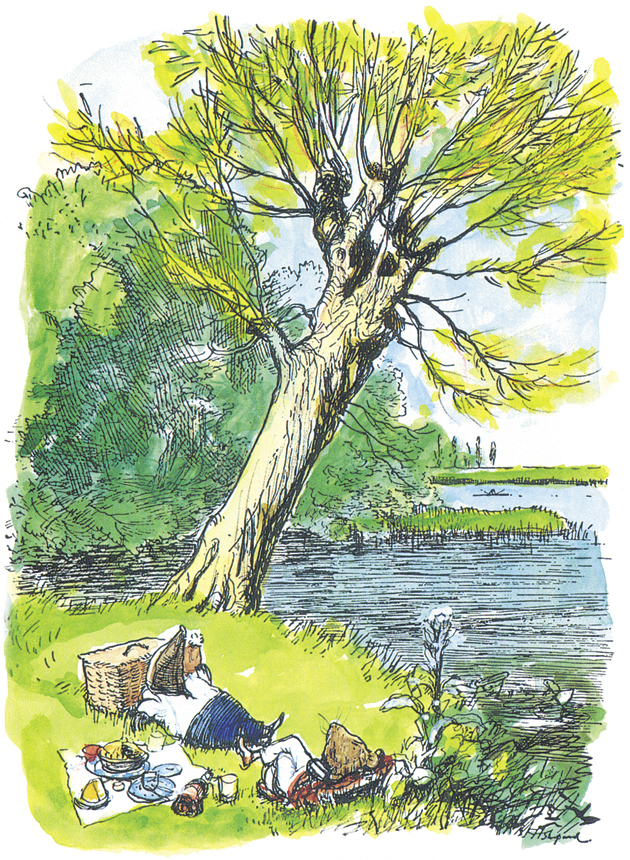

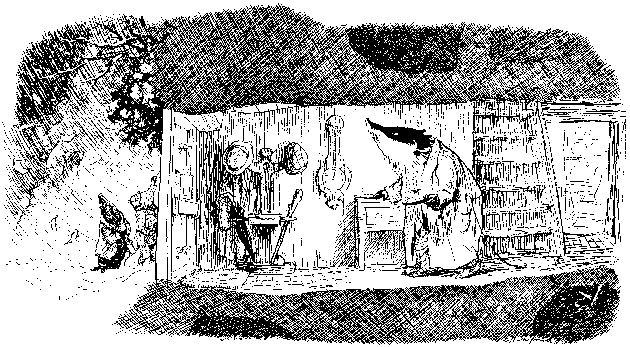

Today The Wind in the Willows (1908) stands as one of the dozen greatest children’s classics of all time. Yet is it really for children at all? Yes, its Riverbank characters are anthropomorphized animals—Mole, Rat, Badger, Otter, and Toad—and yes, E.H. Shepard’s famous illustrations (1931) are as gently winsome as those he drew for A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh books in the 1920s. Nonetheless, to read The Wind in the Willows aloud to a little boy or girl can be disillusioning. Except for the misadventures of the self-dramatizing Toad, there’s really not much action and the mood music of Grahame’s prose sometimes bores the fidgety young. One can certainly understand why the Times Literary Supplement declared in its 1908 review that “children will hope, in vain for more fun.”

Take the book’s single most famous sentence: “Believe me, my young friend,” the Water Rat says to Mole, “there is nothing —absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.” So do the pair go rushing down the river, looking for trouble and adventure, like the English cousins of Huckleberry Finn? No, they float placidly, genteelly along, with a hamper of lavish foodstuffs that might have been packed for them by Harrod’s. They enjoy a picnic, and then return to Rat’s “bijou riverside residence,” where dressing gowns and slippers await them.

In fact, the most memorable passages of this outdoorsy book actually describe cozy interiors—in particular, Badger’s shabby-genteel underground apartments and Mole’s snug burrow in the Christmasy “Dulce Domum” chapter. Nearly every episode culminates in a vision of tweedy bachelor comfort: a simple yet hearty supper, warming drinks, good talk in armchairs by the fireside, heavenly sleep.

And yet for all its comfy domesticity and what Grahame’s biographer Peter Green has rightly called its “timeless, drowsy beatitude,” The Wind in the Willows is also deeply suffused by restlessness, by a periodic yearning for something more from life, by a vague need to break away from the quotidian and routine. Mole suffers from spring’s “divine discontent” and suddenly, exuberantly abandons his home for the riverside. The Water Rat falls under the spell of a seafarer’s romantic tales of faraway places: “Take the Adventure, heed the call, now ere the irrevocable moment passes!” Toad repeatedly surrenders to megalomaniac fugue states in which he views himself as Toad the Great, Toad the Hero, no matter what the actual tawdry circumstances. Virtually all the characters except Badger, that stern voice of rectitude, feel the tug of the road not taken, the allure of a new beginning.

Really, what could be more…middle-aged?

Not surprisingly then, The Wind in the Willows also shows us a world on the wane, when the old ways—the ancient rural traditions of England—are being pushed aside by the steady encroachment of modern civilization. Rat complains that the wash from “steam-launches” has been flooding his living room. In one chapter, we glimpse the great god Pan, but that guardian of the wild vanishes with the day, and we know that fewer and fewer of us will ever hear “the piper at the gates of dawn.”

While The Wind in the Willows certainly has the appearance of a children’s book, this masterpiece nonetheless tends to be most deeply affecting to those past forty. It’s a bedtime story for readers of Henry James, and throughout its pages one periodically hears the faint, wistful cry that haunts Strether in The Ambassadors (1903): “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to.”

2.

Two new editions of Grahame’s masterpiece— The Annotated Wind in the Willows, edited by Annie Gauger, and The Wind in the Willows: An Annotated Edition, edited by Seth Lerer—clearly underscore the book’s complexity and allusiveness. Since Kenneth Grahame was as much a banker as a Riverbanker, it seems particularly appropriate to tot up the respective pluses and minuses of these two handsome albums, starting with the authors themselves.

But before we do this, a word of advice: if you’ve never read The Wind in the Willows, or if you are thinking of giving the book as a gift to a child, don’t choose either of these editions. You want to enjoy the story first, without the distraction and noise of marginal commentary. When first published, Grahame’s masterpiece didn’t even include pictures, though the illustrated versions by E.R. Shepard and Arthur Rackham have since become standard and do add to the book’s distinctive charm. Only when you wish to deepen your understanding and appreciation of this classic should you turn to the what one might call the scholarly Midrash of Lerer and Gauger.

Advertisement

Seth Lerer is a professor of English at the University of California at San Diego, an authority on the history of the English language, a charismatic lecturer (just listen to his high-spirited talks on comedy for the Teaching Company), and the author of the well-received Children’s Literature: A Reader’s History. Annie Gauger has studied at Oxford, spent time as a fellow of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center in Austin, and is a member of the Kenneth Grahame Society. According to her acknowledgments, she worked on her annotated edition for ten years.

As one might guess, Lerer’s approach is that of an academic, Gauger’s that of an amateur, i.e., “one who loves.” Despite a magnificent series of colored plates, Lerer focuses his commentary strictly on Grahame’s text, emphasizing literary echoes and explaining the social context of unusual words and phrases. Gauger, by contrast, packs as much information as possible into her margins, quoting letters, citing well-known critics, and repeatedly pointing out how artists have interpreted various scenes of the book.

For “The River Bank”—the book’s opening chapter—Lerer provides forty- six notes and two illustrations: Rat and Mole sculling along and Rat helping the capsized Mole to shore. Both are by Shepard though neither is identified. Gauger offers fifty-five notes and twenty-seven illustrations, all clearly captioned. Both authors also provide general essays on the book’s artwork: Lerer’s is ten pages long, counting two pages of footnotes; Gauger’s runs to thirty pages, with nineteen illustrations.

In general, Gauger’s edition loads on the extras, starting with Grahame’s letters to his young son Alastair. These are informative because The Wind in the Willows originally began life as a father–son collaboration centering on Mr. Toad. Gauger also includes some letters from Alastair’s governess about the boy’s activities in 1907–1908; a list of the many books in the child’s library; and an essay on The Merry Thought, the magazine that Alastair wrote and drew—and to which his father contributed (along with such notables as the writer May Sinclair and the painter Stanley Spencer). What’s more, Gauger reprints Grahame’s essay “The Rural Pan” and surveys the book’s critical reception—originally quite mixed.

Does all this mean that there’s no contest between these two volumes? Certainly anybody who wants to own just one annotated Wind in the Willows should choose Gauger’s. She simply offers more for the money. Nonetheless, the two editions are surprisingly different and usefully complementary.

Lerer starts with an astute introduction, aiming to bring The Wind in the Willows

into the ambit of contemporary scholarship and criticism on children’s literature, while at the same time exploring the historical and social contexts for the novel’s origins.

He stresses, in particular, the literariness of Grahame’s classic: “The book is the product of a life, but it is, I would suggest, a life of reading.”

To this end, Lerer highlights the author’s borrowings from earlier works of literature. Take “The River Bank” again. Lerer’s notes on various passages point to parallels in the work of Shelley, J.R.R. Tolkien, Max Beerbohm, P.G. Wodehouse, Hans Christian Andersen, and Charles Kingsley, as well as to Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby and Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Gauger makes none of these comparisons.

Similarly, in the annotations to “Wayfarers All”—the chapter in which the Sea Rat recites his adventures to a mesmerized Water Rat—Lerer identifies scores of phrases and images derived from Romantic and Victorian poetry. But while the Sea Rat partly recalls, and is obviously meant to recall, Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Homer’s Odysseus, Lerer nonetheless strains credulity in some of his attributions. The exclamation “Those were golden days and balmy nights!” leads to this note: “Compare Wathen Mark Wilks Call (1817–1890), ‘Manoli: A Moldavian Legend’: ‘thro’ glowing days and balmy nights.'” What’s the point of this tenuous association? Will we actually find anything that illuminates The Wind in the Willows in this piece of forgotten sentimental verse?

Such (probably computer-assisted) source hunting seems both trivial and unpersuasive. Moreover, one’s overall confidence in the results is further shaken when the poet Laurence Binyon is saddled with a never-used first name (Robert), and other names are consistently misspelled—“Henly” for William Ernest Henley; “Hardwick” for Hardwicke Rawnsley. My own favorite misprint, however, occurs in the note explaining the title of Chapter 11, “‘Like Summer Tempests Came His Tears.'” This directs the reader not to Tennyson’s The Princess but to the rather Machiavellian title The Princes.

Advertisement

For many of Grahame’s chapters, Lerer convincingly suggests one or two earlier works as partial templates. The action of “The River Bank” harkens back to Three Men in a Boat ; “The Wild Wood” periodically calls to mind the Sherlock Holmes stories, given that Rat dresses and acts like the great detective, while Mole plays his admiring Watson. In “Mr. Badger,” the crotchety loner’s well-ordered underground home, full of plain, solid furniture, suggests the influence of social reformer and art critic John Ruskin. Even Toad’s adventures when disguised as a washerwoman distinctly mirror those of Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor. The last chapter, “The Return of Ulysses,” not only refers to Odysseus’ cleansing of his house of the ill-mannered suitors, but also, according to Lerer, contains a surprising number of gospel allusions. Certainly, there is a plethora of embarrassing and even creepy religious imagery in “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.”

While these more general analogies seem perceptive, Lerer’s recurrent tendency is to go slightly too far. When Toad meets a gypsy who is cooking stew, the smell is described as “voluptuous.” Lerer states:

Here “voluptuous” means not simply sensuous or tempting, but evil. Toad thinks these cooking smells betoken the ideals of Nature, “mother of solace and comfort.” But they recall the horrors of Milton’s landscapes—for example, in Book II of Paradise Lost where the personified Sin addresses Satan as her father and, in part, announces: “thou wilt bring me soon/To that new world of light and bliss, among/The Gods who live at ease, where I shall Reign/At thy right hand voluptuous, as beseems/Thy daughter and thy darling, without end.”

All this from “voluptuous.” Really?

Where Lerer tends to be fancifully literary, Gauger is nothing if not factual. For instance, in this same section about the gypsy, she not only observes that it pastiches a passage in George Borrow’s semi-autobiographical The Romany Rye but she also presents appropriate extracts from a history of the Romani people. Her researches tell us that Scribner’s printed 4,700 copies of the first American edition of The Wind in the Willows in October 1908, with a second printing of 3,125 copies in December and 3,340 more copies in February 1909. Grahame, we learn, always wrote “till” instead of “until,” and, according to the manuscript, Rat’s outraged cry of “road-hogs!” was originally “stock brokers!” But Gauger’s thoroughness can lead her to sound naively pedantic (e.g., “pinions. The distal or terminal segment of a bird’s wing”) or to go slightly, if charmingly overboard: she lists the names of all nine motorcar companies in 1907–1908 Britain, passes along the recipe for Captains’ Biscuits—referred to in the “Dulce Domum” chapter—and even reprints Grahame’s exacting directions for making coffee.

Such information may provide context, but often seems of doubtful critical utility. Now and again, Gauger can be casually imprecise. She mentions that just before taking on his last commission—his paintings for The Wind in the Willows —Arthur Rackham was supposed to illustrate “a book called A Crock of Gold.” That dismissively mentioned title is actually The Crock of Gold, a classic of modern fantasy—and it does have an author: James Stephens. (James Joyce once said that if he died suddenly Stephens should be asked to finish Finnegans Wake.) Similarly, in discussing Oscar Wilde—a partial model for Toad—Gauger refers to his lover Bosie. Shouldn’t Lord Alfred Douglas be given his real name? These are cavils, but there are also downright mistakes: since the future Lawrence of Arabia didn’t even graduate from Jesus College until 1910, two years after the publication of T he Wind in the Willows, is it likely that Otter “might also be an allusion to T.E. Lawrence, another Oxford man”?

Gauger’s most egregious error occurs when she misses the meaning of the word “smart”:

His shoes were covered with mud, and he was looking very rough and tousled; but then he had never been a very smart man, the Badger, at the best of times.

She insists that Badger is, in fact, “extremely intelligent.” Perhaps he is, but “smart” here means smartly attired, i.e., well dressed. Lerer, the linguist, gets this right. But elsewhere he too errs in word interpretation: after opening his door to the freezing Rat and Mole, Badger says:

Come along in, both of you, at once. Why, you must be perished. Well I never! Lost in the snow! And in the Wild Wood, too, and at this time of night!

Lerer glosses the word “perished” as “Not so much dead, as lost.” Since when did “perish” mean being unable to find one’s way? Badger’s phrase seems an obvious shortening of “you must be perished from the cold” or possibly “perished with hunger.”

While Gauger reproduces many illustrations in the body of her text, the colors tend to be faded and the reproduction quality rather lackluster. The suite of illustrations on coated stock in Lerer’s edition is much more vivid. This matters, since Gauger frequently refers to the work of Grahame’s early illustrators—and not only the two most famous ones, Shepard (1931) and Rackham (1940). Paul Bransom (1913), for instance, portrayed the River Bankers very much as animals, while Wyndham Payne (1927) depicted them as slightly inebriated undergraduates. As it happens, Gauger and Lerer both reproduce a picture—by Nancy Barnhart (1922)—of the imprisoned Toad, sporting a checked suit and vest (and looking more than a little like Evelyn Waugh in his later years). But what color is Toad’s outfit? In Gauger’s reproduction his suit is yellowish plaid; in Lerer’s book it is obviously reddish brown. Which picture tells the truth? Almost certainly Lerer’s.

3.

Many of Gauger’s best critical remarks, and some of Lerer’s, are actually clearly credited quotations from the work of previous Grahame scholars such as Humphrey Carpenter, author of Secret Gardens ; Peter Hunt, a wide-ranging expert on children’s books; and Peter Green, Grahame’s biographer. (Green is generally known as one of the great classicists of our time, but his life of Grahame, published in 1959, may be his finest achievement, as beautifully written as it is scholarly.) In general, the rival editors draw on and usefully summarize earlier research into The Wind in the Willows almost as often as they contribute insights and speculations of their own. Nonetheless, I still hungered for closer critical attention to the book’s inner structure, especially its leitmotifs and verbal repetitions.

For instance, Mole clearly admires Toad and eventually imitates him by dressing up like a washerwoman (when he goes to spread panic among the stoat sentries at Toad Hall). But Grahame also subtly links the two animals rhetorically by their common use of “O My!” during moments of emotional excitement. Again, when Toad is called “the Terror of the Highway,” are we to remember that Mole suffered from “the Terror of the Wild Wood”? Is Grahame quietly pointing out that Toad and the Wild Wooders share a comparable anarchical character? Similarly, what does one make of the “Poop, poop” sound of the motorcar’s horn? It may be onomatopoeic, but can we avoid thinking of its more common baby-talk meaning?

Though both editors rightly point out the Homeric parallels throughout the book, neither mentions the oddity that Mole’s nickname—Moly—is the same as that of the magical flower Moly that safeguards Odysseus from Circe. Just a happenstance? Probably. Yet in the Wild Wood Rat tells Mole that he needs the protection of “passwords, and signs, and sayings which have power and effect, and plants you carry in your pocket….” Also, given the well-established Homeric elements, is it possible that Mole’s adventures might be likened to those of Telemachus, Odysseus’ son? The most youthful and innocent of the Riverbankers, Mole is finding his way in life, hero-worships the glamorous Toad, and is the focus of the first part of the book. Just so in the Odyssey the “Telemachiad” precedes the description of Odysseus’ major adventures. One might even see Rat as an analogue to Pisastratus, who became Telemachus’ intimate friend and traveling companion.

Again, while the stoats, weasels, and foxes obviously represent the cruel, bullying, and petty who are always with us, scholars have suggested that they also symbolize an increasingly restive underclass, one that threatens the established traditions of the squirearchical Riverbankers. Lerer—quoting Peter Hunt—observes that the stoats and weasels’ behavior resembles that of the monkey people in Kipling’s Jungle Books (1894 and 1895). But shouldn’t there be some mention of H.G. Wells and The Time Machine (1895) as well? Mole, pursued by the unseen terrors of the Wild Wood, vividly calls to mind the Time Traveller hunted by the bestial half-seen Morlocks—that imagined end product of a brutalized working class. The Morlocks actually prey on the almost asexual Eloi—the descendants of rentiers and capitalists—who live childish, dreamy lives in a pastoral paradise. Moreover, in this same Wild Wood episode Badger reveals—in a distinctly science-fictional moment—that he actually dwells in the ruins of an ancient human city, Roman no doubt, but much like the ruined and labyrinthine museum that the Time Traveller discovers.

Both Gauger and Lerer also tend to slight Grahame’s The Golden Age and Dream Days. Yet these earlier children’s books often prefigure the themes and even the language of the later masterpiece. Compare Mole’s spring fever—

Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing

—with the opening to “A Holiday,” from The Golden Age :

It was one of the first awakenings of the year. The earth stretched herself, smiling in her sleep; and everything leapt and pulsed to the stir of the giant’s movement…. But the holiday was for all,… the various outdoor joys of puddles and sun and hedge-breaking for all. Colt-like, I ran through the meadows, frisking happy heels in the face of Nature…

A page later we even meet the somewhat Toad-like Harold, “who invented his own games and played them without assistance, always stuck staunchly to a new fad, till he had worn it quite out.”

Lerer neatly labels the attempt to save Toad from his motorcar mania an “intervention,” then invokes contemporary psychology—Krafft-Ebing and Freud—to account for Toad’s obsessive-compulsive behavior. In her turn Gauger cites Green on manic-depression. Yet look at the actual diction of the chapter:

The hour is come!…the work of rescue…the error of his ways… misguided conduct…backsliding… till the poison has worked itself out of his system…violent paroxysms.

This isn’t the language of psychoanalysis, this is the rhetoric of salvation, of temperance, of streetcorner revivalism, and it goes perfectly with Badger’s high-minded and puritanical character.

By contrast, Toad’s own bombastic language derives almost entirely from cheap fiction, advertising, or music hall. As the gaoler’s daughter laughingly remarks, Toad describes his house as if he were a realtor trying to sell it. Not so Mole, who is deeply embarrassed by his simple domicile. Should he be? Rat announces that everything in it is “capital” and “So compact! So well planned” and even remarks that it possesses “every luxury.” To me, these sound like overbright attempts to cheer up a disconsolate friend when, in reality, Mole’s bungalow—adorned with plaster statues of Garibaldi and Queen Victoria, as well as a garish fountain ornament—displays a middle-class kitschiness, despite its owner’s intentions. In a fine BBC dramatization, written by Alan Bennett, Rat is made to sound distinctly insincere, even sarcastic. Certainly, he and Mole—essentially a homosocial couple—can be snappish at times and even downright snide: see their quarrel in “The Wild Wood” chapter just before the discovery of Badger’s snow-covered front door.

As any reader recognizes, The Wind in the Willows —in Lerer’s capsule summary—“traces a tension between Victorian domesticity and Edwardian change.” In its last pages the upstart canaille of the Wild Wood are soundly defeated by a band of country gentlemen, but only temporarily. Toad, we know, will not really reform. Grahame said as much in a letter. “He was by nature incapable of it.” And the loathed machine age, the ill-mannered, clamorous modern age, will eventually triumph. By now, of course, Toad Hall has become a bed and breakfast for American tourists. Buses leave hourly for tours of the Wild Wood. No swimming is currently permitted on the river, except at the weir, where the lifeguard and refreshment stands are located. For insurance reasons, there is a ban on messing about in boats.

Sigh. At least Kenneth Grahame’s exquisite prose remains:

When the girl returned, some hours later, she carried a tray, with a cup of fragrant tea steaming on it; and a plate piled up with very hot buttered toast, cut thick, very brown on both sides, with the butter running through the holes in it in great golden drops, like honey from the honeycomb. The smell of that buttered toast simply talked to Toad, and with no uncertain voice; talked of warm kitchens, of breakfasts on bright frosty mornings, of cosy parlour firesides on winter evenings, when one’s ramble was over and slippered feet were propped on the fender; of the purring of contented cats, and the twitter of sleepy canaries.

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory