In 2004, her eighty-eighth year, Jane Jacobs published her last book, Dark Age Ahead, in which she mentioned in passing that “sooner or later (the housing bubble) would burst…as all bubbles do when their surfaces are not supported by commensurate increases in economic production.” Dark Age Ahead was uncharacteristically gloomy and not widely read: a pity, for it would be two years before the economist Nouriel Roubini and others described an unstable housing bubble and warned of trouble.

Jacobs is an intellectual legatee of Benjamin Franklin, a genius of common sense, as her biographers, Glenna Lang and Marjory Wunsch, aptly call her. She saw through institutional walls to the malfunctions within. This facility, combined with a strong but gentle polemical style and a Napoleonic ability to recruit and deploy citizen armies, rescued vital Manhattan neighborhoods including Soho and much of Greenwich Village from ruin fifty years ago by city planners and developers saturated with high-rise ideology and ravenous for federal highway and slum clearance money. The frustrated tone of Dark Days Ahead is that of a virtuoso prophet near the end of her life during the Cheney-Bush years, trying to alert her readers to the oncoming darkness, more threatening by far than the attack on Manhattan by planners and developers a half-century ago.

Perhaps the problems she cites in her final book did not seem as menacing to others as they did to her—the indifference of government to the urgent needs of citizens; a university culture that awards credentials rather than encourages learning; the failure of professional self-regulation exemplified by fraudulent accounting practices. She wrote Dark Age Ahead in the aftermath of the Enron scandals before the crimes of the bond-rating agencies and the mortgage industry emerged and the financial arrangements between physicians and drug companies were exposed. Or perhaps these and other signs of rot that she mentions are now so embedded in everyday life as to seem normal.

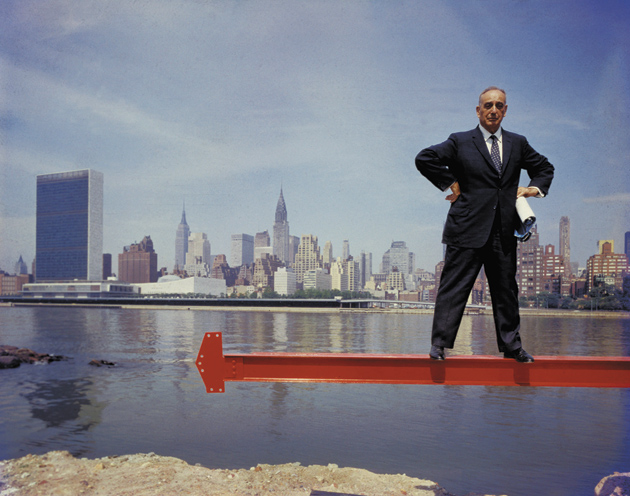

A complacent public had not been a problem for Jacobs fifty years ago when she declared that New York City’s planning establishment led by the megaplanner Robert Moses was parading naked down Fifth Avenue to Washington Square Park, promoting “a plan” to extend Fifth Avenue “through” the Greenwich Village “park where Jacobs brought her own children to play.” “Moses,” writes Anthony Flint in his fine account of the opening skirmish of the Jacobs/Moses wars of the 1950s and 1960s, “wanted to provide better access” and a Fifth Avenue address “to his massive urban renewal project just south of the” historic park. Jacobs and her neighbors wanted to protect their patch of green, the vital center of Greenwich Village. “The collision course was set.”

Flint writes that the park “was steeped in history.” For Henry James, the author of the novel Washington Square, the park was

“a place of established repose…as if the wine of life had been poured for you…into some pleasant, old punch bowl.” …Wharton,…Whitman,…Poe,…Crane were drawn there. Then [came] the artists…De Kooning,…Hopper,…Pollock …Kerouac…Dylan…Baez, Peter, Paul, and Mary…. Home to protests, marches, riots…the Park had come to symbolize free speech, political empowerment and civil disobedience…. But most of all Washington Square Park was a place [where one could enjoy] grass and trees in…a city that could feel very paved and gray….

Dogs were welcome, as were musicians, chess players, and street performers. Children could safely play. Washington Square Park is small, two blocks long by two blocks wide. Moses’s proposed four-lane extension of Fifth Avenue traffic would destroy it.

Jacobs learned of Moses’s plan from a flyer distributed by a citizens committee that had formed to protect the park. She and her husband, an architect, signed on. She also wrote to Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr.:

I have heard with alarm and almost with disbelief, the plans to run a sunken highway through the center of Washington Square. My husband and I are among the citizens who truly believe in New York—to the extent that we have bought a home in the heart of the city and remodeled it with a lot of hard work (transforming it from a slum property) and are raising our three children here. It is very discouraging to do our best to make the city more habitable and then to learn that the city itself is thinking up schemes to make it uninhabitable. I have learned of the alternate plan of the Washington Square Park Committee to close the Park to all vehicular traffic. Now that is the plan that the city officials, if they believe in New York as a decent place to live and not just rush through should be for. I hope you will do your best to save Washington Square from the highway.

When he saw this letter, if he did, the mayor could not have known that he was reading a declaration of war, one that would rage for ten years and affect his city and himself profoundly.

Advertisement

I first heard of Jane Jacobs in 1956 when a friend suggested I read her article “Downtown Is for People” in Fortune, which laid out the case against Le Corbusier’s Radiant City ideology, which had infected much city planning of that period, including that of New York’s Robert Moses and East Berlin’s Stalinallee. “These projects will not revitalize downtown; they will deaden it,” she wrote.

They will be spacious, parklike, and uncrowded. They will feature long, green vistas. They will be stable and symmetrical and orderly. They will be clean, impressive, and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery.

I shared her objections. The absurdity of urban renewal in New York and elsewhere was by then obvious and oppressive. Like Jacobs, I liked the “cheerful hurly-burly” of the city’s street life; its mixed industrial, commercial, and residential neighborhoods; its lively and diverse manufacturing economy of light industry, garment and shoe manufacture, food processing, publishing, metalwork, electronics, graphics, and so on; its openness and the feeling one had of possibility. New York City with its conurbation in those days was the largest manufacturing employer in the United States but unlike Detroit and Pittsburgh was not smothered by a dominant industry.

There were problems: racial segregation, slums, crime, redlining, a calcified school system, endemic corruption, but high-rise slum clearance was not the solution. It was one of the problems. Moreover in 1956 my late wife Barbara and her neighbors inflicted upon the all-powerful Robert Moses his first major defeat by an aroused community when a few dozen angry mothers, accompanied by their children, defied an attempt by his bulldozers to usurp the local playground by enlarging a parking lot for a Central Park restaurant. I was ready to admire Jacobs before I met her.

I was then in the book-publishing business and offered Jacobs a contract for a book based on her Fortune article, which I had reprinted in a collection of essays called The Exploding Metropolis. Two years later she completed The Death and Life of Great American Cities, still in print after fifty years. I also edited all but the last of the several books that followed, all composed on the old Remington on which she had written Death and Life. Editors and their authors seldom form deep friendships for the same reason that psychiatrists and their patients keep their distance: intimacy and candor don’t mix. But Jane and I were nicely attuned. Still, there is much in the delightful books by Lang and Wunsch and Flint that I did not know, especially about her early years in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where her father had been the local doctor. She had been a defiant high school student with a sense of humor, a keen ear for cant, outspoken: a troublemaker even then. I knew that she had chosen to skip college except for briefly attending courses in the extension program at Columbia where she remained long enough to write her first book, Constitutional Chaff (1941), about the rejected proposals for the United States Constitution, which was published by Columbia University Press, an impressive debut for a self-educated scholar at the age of twenty-five.

Nevertheless, like many authors with large ambitions she preferred not to discuss her juvenilia. And I knew that she had come to New York looking for a job in journalism, but I did not know that after a few false starts she found a place at Iron Age, a trade magazine. For Iron Age in 1943 she wrote that Scranton, which had lost 25,000 jobs when its anthracite mines closed, would be an excellent site for armaments production. The article was widely reprinted and Jane was credited with having helped bring an airplane parts plant among other wartime businesses to her hometown. Though she had scored a coup for Iron Age as well as for Scranton, she was fired when she defied a warning from her editor and became a union representative in the magazine’s office. Her gift of common sense rendered her helpless to accept the world as it was.

Moses had had his eye on Washington Square Park for years. In 1935 he proposed to round off its corners and turn it into a traffic oval. The neighborhood rebelled and he backed off. In 1939 he tried again. This time an opponent denounced the oval design as a bathmat, a trope that became a rallying cry and once again Moses withdrew: the triumph of imagery over brute force. Then, perhaps partly to avenge these instances of lèse-majesté, Moses in 1952 revealed his plan to extend Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park to the massive development to the south and then to build a half-mile extension further south to the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway. This monstrosity was to be a ten-lane elevated link along Broome Street connecting the Holland Tunnel from New Jersey to the Manhattan and Williamsburg bridges leading to Long Island, thus creating an interstate route through lower Manhattan eligible for a 90 percent federal highway grant.

Advertisement

This useless project, along with its ramps, would obliterate the area between Houston and Canal Streets, now known as Soho, and cut lower Manhattan in two just below the waist. Moses’s intended depredation of lower Manhattan should not detract from his great achievement as a maker of beaches, parkways, and bridges for New York’s mobile middle class, or from his hundreds of parks and baseball diamonds, but the revitalization of Manhattan demanded the artistry of a watchmaker. Moses’s tools were raw political power, federal money, and Radiant City ideology.

As for Manhattan’s intricate design, he simply didn’t get it. Moses argued that Fifth Avenue traffic, as it approached its terminus at Washington Square, would be intolerable without his planned extension. Had he removed his ideological spectacles he would have seen what Jacobs pointed out in rebuttal and what remains obvious to any motorist and passerby to this day. Drivers approaching the dead end of Fifth Avenue at Washington Square turn off well before the park, leaving that final stretch of the avenue relatively free of traffic. The same phenomenon is evident as Lexington Avenue approaches its terminus at Gramercy Park. Traffic melts away as drivers divert to the network of side streets, a tendency that seems to have inspired the recent plan to exclude Broadway traffic from Times and Herald Squares.

For Jacobs the skirmish of Washington Square was an education in strategic civil disobedience. Moses’s characterization of the park’s defenders as “stupid and selfish” helped his opponents. So did the local politicians whose fate was in the hands of the neighborhood voters and not in those of Moses’s City Hall backers and upstate power brokers. Lewis Mumford, in The New Yorker, condemned Moses’s “insolent contempt” for common sense and his “unworthy cause,” whose beneficiaries were “the realtors and investors” for whose sake he was planning “to deface and degrade Washington Square.” Week after week The Village Voice and TheVillager amplified this criticism. Moses held his ground until Carmine de Sapio, a local political boss with powerful connections, called the park “one of the city’s most priceless possessions,” and said it shouldn’t be disturbed. Later that year at a Board of Estimate meeting Moses tried and failed to revive the project, arguing that “there is nobody against this—nobody, nobody, nobody, but a bunch of…mothers!” His plea was ignored.

Jacobs submitted the manuscript of Death and Life in late January 1961. A month later she opened The New York Times to discover that Greenwich Village from the Hudson River to Washington Square Park, the very area celebrated in Death and Life as a model of urban vitality, had been selected for slum clearance. Her own house at 555 Hudson Street was right in “the cross hairs.” Moses no longer led the City Planning Commission. The job now belonged to James Felt, the scion of a real estate family and himself the founder of a company that assembled parcels for development and relocated evicted tenants. Though Felt was now Jacobs’s nominal adversary she was convinced that Moses, the real power behind the West Village project, sited her house in the line of fire. I took this seriously: Jane was not paranoid. Moses was spiteful and had never hesitated to uproot entire neighborhoods.1

Once again the neighborhood rallied under Jacobs’s leadership, recruited local politicians, created a David and Goliath narrative for the press, and followed Jacobs’s advice not to negotiate for a better deal but to “kill this project entirely because if it goes through [in any form] it can mean only the destruction of the community.” When the plan is defeated completely “we will look for an alternative. We want enforced conservation of the buildings, not their destruction.” But the sponsors of the West Village plan, chastened by Moses’s defeat in the skirmish of Washington Square, had also prepared for battle. They mustered what claimed to be a few community groups in support of the redevelopment scheme. Jacobs had by this time created a neighborhood spy network staffed partly by children on the lookout for developers’ agents seeking signs of decay that would justify a slum designation and therefore federal slum clearance funding. The children quickly learned that the agents were working for David Rose Associates, a developer whom Felt had secretly chosen to undertake the West Village project.

Meanwhile Jacobs had received a communication from a public relations firm whose typewriter had a faulty R, the same misshapen letter that was turning up on press releases issued by the opposing community groups. An adult spy volunteered to visit the public relations firm where he noticed a telegram from Rose Associates on a desk. This evidence of a backroom deal, which Jacobs revealed at an angry neighborhood meeting, was decisive. “It’s the same old story,” she said. “First the builder picks the property, then he gets the Planning Commission to designate it [a slum], and then the people get bulldozed out of their homes.” The taint of corruption upended the project. Felt soldiered on but could not regain his footing against an energized neighborhood. De Sapio withdrew his support from the West Village plan. So did Mayor Wagner, who was facing a primary challenge in which his opponent promised to kill the West Village plan. Wagner had no choice.

The West Village was saved, but as with all victories, unintended consequences ensued. Clarence Davies, a Felt ally and head of the Housing and Redevelopment Board that

replaced [Moses’s] Committee on Slum Clearance wrote…”that if the Village area is left alone and if no middle-income housing is projected by the Board…eventually the Village will consist solely of luxury housing, which we, of course, will be powerless to prevent…. This trend is already quite obvious and would itself destroy any semblance of the present Village that [Jacobs and her allies] seem so anxious to preserve.”

The term was not yet in use but Davies had foreseen the gentrification that would within twenty years turn the Village into some of most expensive real estate on earth. The mixed-income neighborhood of dockworkers and middle-class households and artists’ lofts that Jacobs championed would become the victim of its own charm. There would be little room for working-class families or struggling artists in the Greenwich Village that Jacobs fought to preserve. “Her vision of organic city growth,” Flint writes, “would do little to curb gentrification.”

Predictably, Death and Life, which was published at about this time, was welcomed by the libertarian right and denounced by social engineers on the left. Like Rachel Carson’s purified natural environment and Betty Friedan’s gender-neutral ethic, Jacobs’s self-creating community of mixed uses transcends the partisan issues of left and right by positing a utopian goal as a practical possibility. The widely popular books by these authors are the inspirational literature of today’s secular religion. Though human nature—the ineluctable serpent in our garden—shapes the world we live in to the detriment of the one we wish for, these visionary writers offer a hope and a plan. They call forth our better angels. Without them our world would be worse than it is.

The war over the monstrous Lower Manhattan Expressway, a projected ten-lane elevated link running along Broome Street and connecting the Holland Tunnel to the East River bridges, would be long and painful. Jacobs and the neighborhood coalition prevailed. But the nine-year struggle until the plan was finally abandoned convinced Jacobs that if she wanted to write other books she must leave New York. Her two sons would soon be of draft age. Her husband, an architect, was designing hospitals in Canada. In 1968, with the expressway battle effectively over (though the mopping up would take another three years), she sold her Hudson Street house and moved with her Remington to Toronto.

There she wrote several books including two in which she argued brilliantly that cities preceded agriculture in the history of economic development: that hybridization and husbandry could not have evolved from hunting and gathering cultures but from nascent cities where plants and animals were exchanged for local goods such as obsidian or some other necessary materials controlled by primitive city dwellers, who then discovered which animals could be tamed and bred and which must be killed at once and which plants could be cross-bred with others to produce a better variety.2 She remained in Canada until her death, visiting New York only now and then, and refusing honorary degrees in keeping with her disapproval of academic credentialing. Were she to visit today she would be horrified by Brooklyn’s Atlantic Yards project as she was several years ago by the now defunct plan to erect a new Yankee stadium on the site of the West Side Railyards.

Millions of federal dollars had been at stake on the Lower Manhattan Expressway across Broome Street along with thousands of union jobs, architects’ and lawyers’ fees, developers’ profits, and political favors bought and sold. At risk was the survival of lower Manhattan including Chinatown, Little Italy, and the southern reaches of Greenwich Village. Had Moses won, the damage to the city would have dwarfed the physical wreckage of September 11. Today these neighborhoods comprise Soho and the thriving Asian and Hispanic settlements to the east, an area of incalculable urban vitality and generators of untold wealth. I live on Broome Street, which Moses would have destroyed, promising vast traffic jams should his scheme be rejected.

Broome Street today is a typical Manhattan crosstown route, lined for much of the way by landmarked cast-iron buildings, handsome relics of the 1850s when Soho had been Manhattan’s grand commercial center. Broome becomes congested only as it approaches the Holland Tunnel at rush hour. Today heavy traffic rumbles between the Manhattan Bridge and the tunnel along Canal Street, three blocks to the south of Broome, as it has for years, an unanswerable rejoinder then and now to Moses’s claim that the city needed an alternative route between the same two points. Peter J. Brennan, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council, warned that if the wishes of “our city planners” were thwarted, “our city would still be a cow pasture with Indians running around.” The only rustic detail of note on Broome Street today is a memorial tree planted in front of the church whose pastor inspired the nine-year struggle to defeat the expressway and invited Jacobs to help.

The complex history of this confrontation, which led to Jacobs’s decision to leave New York for the relative tranquility of Toronto and to Moses’s retirement from public life to a beachfront community on Long Island, is brilliantly reconstructed by Flint. The battle of the expressway was in its way as decisive as Waterloo or Stalingrad, for had it ended differently, who can say what would have become of Manhattan, with a useless, decaying expressway, requiring by now extensive repair, instead of the economic vitality of Soho and the rapidly gentrifying Lower East Side, one of the world’s great urban environments?

The expressway battle coincided with the Vietnam protests and became a factor in the widespread loss of confidence in government by both left and right. But if the expressway opponents despaired of government they must have acquired a compensating respect for their own power under wise leadership, a taste of the utopia by practical means implicit in Death and Life. In this sense the Jacobs/Moses war was educational, a living curriculum now encapsulated in Flint’s excellent study, while Jacobs’s exemplary life story is well enough told by Glenna Lang and Marjory Wunsch to engage young readers and interest their elders as well.

This Issue

August 13, 2009

When Science & Poetry Were Friends

A Very Chilly Victory

-

1

FDR, who disliked Moses, rejected his plan for a bridge linking the southern tip of Manhattan to Brooklyn. Moses responded by relocating the city’s aquarium from Battery Park to a remote location east of Coney Island, hoping perhaps to punish Roosevelt’s Manhattan voters. ↩

-

2

The Economy of Cities (Vintage, 1970) and Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life (Random House, 1984). ↩