A crucial fact about today’s Congress, and one that even many politically astute observers may not fully appreciate, rests in the vast ideological differences between the two congressional parties. I don’t mean by this that the Democrats have become uniformly liberal and the Republicans uniformly conservative, which is the standard grievance issued by the press, but rather that only the latter has happened—and that it has happened with surprising speed.

Consider, for example, a comparison of the makeup of the House of Representatives today versus twenty years ago, looking at the 101st Congress (1989–1990) and the current 111th Congress. The parties’ numbers of seats in both congresses is about the same: the Democrats had a 261–174 advantage in 1989 and enjoy a 258–177 margin today. But the changes in how each party got to those numbers reveals a great deal.

I made a count of each state’s House delegation in both congresses. In the twenty-year time frame, the Democrats have expanded their membership in twenty-two states, and the Republicans in eighteen. That sounds fairly even. But when you look at the particular states in which each party has gained, you see that the Democrats have actually expanded their reach into some states and regions where their party was traditionally weak, while the Republicans—after going as high as around 230 seats when they were in the majority before being demoted by the voters in the last two elections—have mostly increased their margins in states where they had power already. These include the states of the old Confederacy, which started turning Republican in the mid-1960s and by the late 1980s were moving strongly toward the GOP; a few border states; and the Great Plains states that have always been predominantly Republican.

So, for example, the Republicans have added twelve seats to their 1989 total of eight in Texas, a delegation in which they now control twenty seats. The Democrats now control twelve. (In 1989 the Democrats had nineteen, the Republicans eight.) The Republicans have added six in Georgia (which the Democrats also controlled back then), five in Florida, two each in North and South Carolina, two more each in Alabama and Louisiana, and one more in Tennessee. Add a two-seat increase in Oklahoma, which was not yet a state during the Civil War but is today considered Southern politically, and the result is that the GOP today controls thirty-four more House seats in the South than it did two decades ago. The party has also added one each in border and Great Plains states—Missouri, Kentucky, Nebraska.

The Democrats over the same time have, to be sure, added to their totals in the one geographic region where they already enjoyed clear dominance, the Northeast. They have added six seats to their New York delegation, where the GOP has virtually disappeared. (Democrats control the state twenty-seven to two, with William Owens’s November 3 victory in the closely watched upstate special election.) As is well known, there are no longer any Republicans in the House from New England. This seems unsurprising and in some respects is, except that New England includes New Hampshire, for many years a Republican bastion. Republicans controlled both of that state’s House seats in 1989, but Democrats control both now.1 Some Democratic-leaning states in the North have lost population, and thus House seats; but proportionally, Democrats have typically gained in these states: Pennsylvania, say, where a twelve-to-eleven advantage in 1989 (52 percent) has today become a twelve-to-seven advantage (63 percent).

But the Democrats have done more than reinforce their stronghold. Most striking is Arizona, where a four-to-one GOP advantage in 1989 has become a five-to-three Democratic lead today. Likewise in Colorado—the parties evenly split the state’s six House seats in 1989, but today the Democrats hold a five-to-two edge. In New Mexico in 1989, the Democrats held just one of the state’s three seats; today they control all three.

Finally, Democrats still maintain advantages in Arkansas and Mississippi. This is partly for vestigial reasons (old habits that predate even Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon), partly because of large black populations, and partly because Democratic legislatures have drawn friendly voting districts.

To summarize, then, the Republican House delegation is far more concentrated today in its two regions of strength, the South and the Great Plains, than it was in 1989. Then, 22 percent of its members came from the states of the old Confederacy. Today, 35 percent do. And as the GOP has retreated, the House Democrats—after their own period of retrenchment from 1994 until 2006—have grown. The Democrats gained in their Northeast redoubt, though only by fourteen seats. The Democrats’ largest percentage gains have come in the mountain states, where their representation has almost doubled, from nine to seventeen. And in stark contrast to the Republicans’ pitiful performance in the Northeast, the Democrats have managed to hold more than fifty seats in the South, and they are not limited to districts that are urban, with a majority of African-Americans or Hispanics.

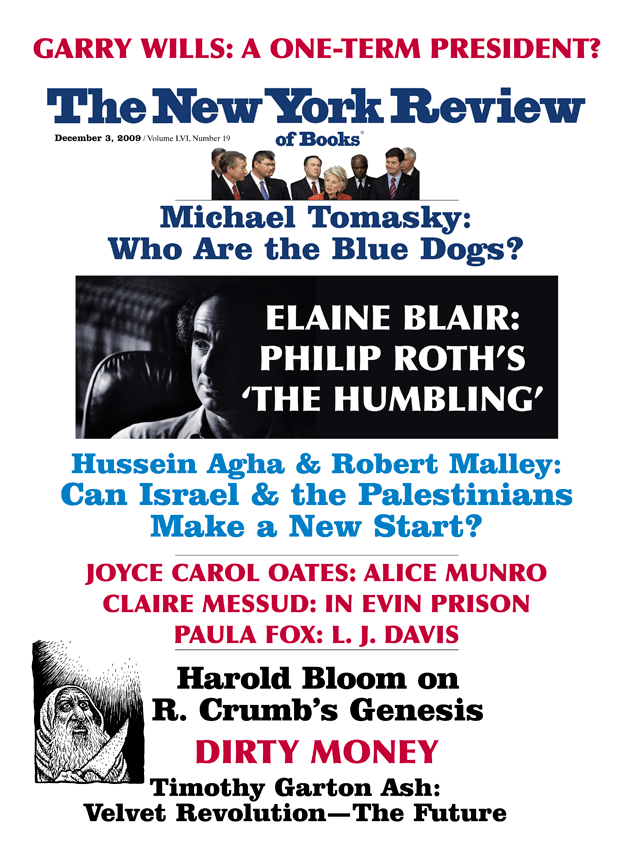

Advertisement

What this means is that the Democratic congressional party has become far more ideologically diverse than the Republican one. In theory, and sometimes in practice, this can be a good thing. But it means that Democrats simply can’t act with the kind of unanimity one sees among Republicans. There is too much disagreement within the caucus.

One faction, particularly vocal in recent months, is the Blue Dog Coalition—the fifty-two House members who represent some of the newly won districts (and some old ones) and who say they stand for moderate or even conservative principles. The inspiration for the name comes from several sources. It’s a play on the old phrase “Yellow Dog Democrat”—for those who’d sooner vote for a yellow dog than a Republican. It expresses the sense of the group’s founders, in 1995, that they were being “choked blue” by their party’s liberals. And most surprisingly, it is partly homage to the Cajun artist George Rodrigue, specifically his famous faux-naif painting of a blue Chihuahua, copies of which adorned the office walls of two Louisiana members who hosted early organizational meetings. There is no official Blue Dog Senate group, although there is a sixteen-member Moderate Dems Working Group, formed last March by Evan Bayh of Indiana. It has yet to exert influence as a group, in part because in the Senate each individual senator has far more power than an individual House member.

The Blue Dog Coalition has proven attractive to members who, for various reasons, want to be seen as having a centrist credential. One finds entrenched veterans like Jane Harman of California’s district covering the southern beaches; she is one of the House’s richest members (her husband owns Harman-Kardon, which makes stereo equipment) and is liberal on almost all matters except national security, having supported the Iraq war and survived a 2006 primary challenge from a candidate who criticized her for doing so. And there are newcomers with wobbly support in their districts—the wobbliest of all, by seeming consensus among Congress-watchers, being Walt Minnick of Idaho, a one-time Nixon aide of libertarian bent who resigned in protest over the Saturday Night Massacre, became a Democrat in 1996, and won a close race in a very Republican district. He was helped along when his opponent was caught heckling a Minnick aide during a television interview (and by $900,000 of his own money). Just six members of the fifty-two-member Blue Dog group are women, two are Latino, and none is African-American. Twenty-one come from Southern or border states.

The cochair for policy is Baron Hill of Indiana, whose district includes liberal-leaning Bloomington but much farm country besides. A high school basketball star, Hill was inducted into the state basketball hall of fame alongside none other than Larry Bird in 2000, which surely has not hurt him. The cochair for administration is South Dakota’s at-large representative, Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, a cautious moderate who won her seat in part because the Republican incumbent resigned after having been convicted of vehicular felony manslaughter. She is considered a charismatic rising star in the party. The new cochair for communications, as of October 7, is Utah’s Jim Matheson, a Salt Lake City energy executive and son of a former governor. He was first elected in 2000 to a safe Democratic district that was subsequently redrawn by the state legislature to be much more conservative.2 He replaced as cochair Charlie Melancon (pronounced muh-LAW-shawn), from a Louisiana bayou district devastated by Hurricane Katrina—a district that includes, according to the 2010 Almanac of American Politics, “the remains of St. Bernard and Plaquemines parishes.” And the whip is another former athlete, Heath Shuler of North Carolina, who starred as quarterback for the University of Tennessee, flamed out in the NFL, and impressively defeated a well-financed GOP incumbent in the Democrats’ 2006 sweep.

That year turned out to be pivotal, not just for the Democrats but for the Blue Dogs in particular. Rahm Emanuel, then an Illinois congressman in charge of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, actively recruited moderates and conservatives who could win in some of the districts made newly contestable by George W. Bush’s unpopularity. The Democrats won thirty seats that November, about twenty of them captured by candidates whom Emanuel strongly encouraged and supported. Not all Emanuel recruits were winners—in fact, three centrists lost primaries to their more liberal counterparts, who ended up defeating Republicans anyway. But the Blue Dogs expanded their numbers somewhat after that election, and also their influence.

Advertisement

To look at the Blue Dogs’ voting records as scored by the various interest groups, they don’t always stand out as particularly conservative. Herseth Sandlin, for example, earned a 90 percent score from Americans for Democratic Action in 2007. Hill received a 91 from the American Civil Liberties Union in 2008. Many of the group’s members are actually fairly liberal on a range of matters. It’s when the big issues take center stage, especially ones that pit government spending against deficit reduction, that the Blue Dogs bark.

The Blue Dogs had reservations about the $819 billion stimulus bill along the expected lines—too much discretionary spending, too unconcerned about the deficit. In the end, though, only ten of them voted against it, along with one other Democrat, Paul Kanjorski of Pennsylvania, and of course every Republican. Of the Blue Dogs’ four leaders at the time, only Shuler opposed the stimulus package. Nine of the eleven Democratic dissenters represent districts in which John McCain beat Barack Obama.

That these blue politicians represent red districts is a fact to which the party leadership is usually sensitive. Reacting to the stimulus vote, a spokesman for Speaker Nancy Pelosi said: “Many of the districts are more conservative, and they campaigned on fiscal responsibility, and we understand that.”3 Indeed the degree of understanding may have gone even further. Jim Cooper of Tennessee, considered one of the coalition’s more serious legislators, said in a radio interview in early February that he was given leave by the White House to vote against his party’s House leadership. “Well, I probably shouldn’t tell you this, but I actually got some quiet encouragement from the Obama folks for what I’m doing,” said Cooper.4

The political truth is that the Democrats now have exactly forty votes to spare in passing legislation. The speaker’s staff, and of course the members themselves, know very well which members can most, and least, afford to cast a vote that might be seen in their districts as too liberal. The stimulus, during Obama’s honeymoon period, was comparatively easy to get through Congress. On an issue like the cap-and-trade bill to control carbon emissions, matters became far trickier. Forty-four Democrats opposed the legislation—that is, it would have failed without the eight Republicans who supported it (Pelosi’s staff knew they had these eight and so were able to release more Democrats to vote no). Twenty-nine Blue Dogs opposed the bill. Collin Peterson, who represents a largely rural Minnesota district, struck a bargain over the bill with California’s Henry Waxman that led several other Blue Dogs to vote for it—and led many advocates to complain that it had been indefensibly watered down, which was the reason several liberal Democrats, such as Ohio’s Dennis Kucinich, opposed the measure.

Which brings us to health care. The Blue Dogs spent the spring and summer chary of the entire issue. Mike Ross of Arkansas, in whose district McCain beat Obama by 58 to 39 percent,5 is the leader of the Blue Dogs’ health care task force and a member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, one of the key panels proposing reform. He emerged over the summer as an outspoken opponent of large-scale reform. There were certainly moments, during the bumptious summer of town-hall outrage, when it seemed that the Blue Dogs might kill health care reform before it even got out of the relevant committees.

The Blue Dogs’ tactics on health care have been cast by the press as largely motivated by politics, and obviously they do have political concerns. But they have raised substantive issues as well. Not all of those have been conservative in nature—Cooper, for example, an acknowledged expert on the topic, initially favored a bill that would be more like the one proposed by Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, which would have taken steps to do away with the present system of employer-sponsored coverage. It was thus a more radical departure from the status quo than anything under current consideration.

But in the main, the Blue Dogs’ protests have had to do with the three top priorities they list on their Web site: controlling costs (starting with the demand that reform be deficit-neutral); increasing value (which means eliminating waste); and improving “access” by making it easier to get health care. Another major concern has centered on the reimbursements to rural doctors and other providers, which are lower (sometimes far lower) in rural areas than in cities for a range of reasons. Ross, in a July 29 press release, listed five substantive items that needed to be addressed, including a reduction in employer-mandate requirements for small businesses, more generous reimbursements to rural hospitals under a public option, and a guarantee “that a public plan will not be forced on anyone and will negotiate rates directly with providers.”

While the topic wasn’t on the Blue Dogs’ official list, the funding of abortion procedures was an issue for a time. This was settled to the satisfaction of most Democrats with an amendment by Lois Capps of California ensuring that any abortion procedures that were covered would have to be financed through private money generated by policyholders’ premiums, not public funds. Even this isn’t good enough for one anti-choice Democrat, Bart Stupak of Michigan—not, incidentally, a Blue Dog—who has continued to push for further restrictions.

Right after Ross issued his press release, he reached a hard-fought accord with Waxman that led to a version of the bill being approved by Waxman’s committee by a 31–28 vote on July 31. Eight Blue Dogs sit on that committee, and five of them, including Ross, backed the bill, even though Ross’s conditions had largely not been met. They have been met now—which surely reflects to some extent Ross and the coalition’s muscle, and the leadership’s fear of losing too many of their votes.

The final House bill, which Pelosi unveiled on October 29, also reflected the leadership’s fear of a Blue Dog revolt. It contained a public option, but a weak one, tied not to Medicare reimbursement rates as liberals had hoped but based on negotiated reimbursements. The Blue Dogs preferred this—as the insurance industry surely does—and moderate Democrats stood firm against a “robust” public option as the leadership made its final “whip counts” in advance of releasing a bill. One study that came out over the summer found that the coalition’s political action committee had raised more money in the first six months of 2009 than in the entire two-year 2003–2004 period—$1.1 million, with nearly $300,000 of that coming from the health care industry.

So the Blue Dogs have evidently triumphed on the question of the public option. Their resistance to it always had at its core a contradiction. Their great concern is cost containment, and no more effective cost-container has been proposed than the robust public option; yet many were against it. There is also the fact that as a group, the Blue Dogs tend to represent districts that are poorer—districts where more people could really benefit from a public option. And this is where their concerns have frankly quite often come across as less substantive than political or electoral.

After the Waxman committee vote, Ross was quoted as saying: “I couldn’t get 20 percent of the vote in Chairman Waxman’s district, and he couldn’t get 20 percent in mine.”6 This is the kind of line—especially the second part—that tends to set heads in Washington nodding in knowing agreement, reinforcing as it does the notion that big-city liberals just don’t understand what it’s like “out there.” But is it true?

Certainly, Blue Dogs and other rural Democrats can’t vote like Manhattan’s Jerry Nadler. Everyone understands that. But it’s also not entirely clear that one or two controversial votes would endanger many of these legislators. The current House includes forty-nine Democrats who won in districts where McCain beat Obama, and thirty-four Republicans who won in districts that Obama carried. Forty-nine is a large number, nearly one in five members of the total number of House Democrats. And in many of these districts, McCain beat Obama handily—by 15 or 20 or even 30 percentage points.

And yet all but a small number of these Democrats won their own races by a greater margin than McCain’s over Obama in the district. Thirty of them beat their GOP opponents by 10 percentage points more than McCain beat Obama. I calculated these numbers in late July, comparing the Democrats’ victory margins to McCain’s, determining each Democrat’s “margin versus McCain”(MVM).7 Ross, for example, ran unopposed, scoring an MVM of +67. Melancon also ran unopposed, producing an MVM of +76. Herseth Sandlin’s margin was +28, Shuler’s +21. Only eight of the forty-nine had negative margins. Minnick’s, for example, was –25. He and a handful of others have every right to proceed with caution.

But for the vast majority of members of Congress, once you’ve been elected and reelected once or twice, it takes either a pretty big scandal or a rare historical tidal wave (as in 1994) to produce defeat. Members know this—in fact, they typically know exactly how many percentage points a certain vote might cost them at the polls. One begins to suspect that some Blue Dogs don’t really fear losing as much as they fear facing a semicredible opponent and actually having to campaign hard for a change.

That said, it is true that they “campaigned on fiscal responsibility,” as the Pelosi spokesman put it after the stimulus vote. What Blue Dogs typically want out of legislative negotiations, one leadership aide told me, is to be able to go back to their districts and say to their voters that they managed to wrest this or that concession out of the more liberal leadership. This aide spoke of “thousands of hours of meetings” with individual legislators seeking to change health care legislation in large ways and small: “If you can’t go back to your district and say, ‘I’ve changed this bill to reflect you voters,’…you have to be able to point to something that you did that made the bill better.”

Such concessions to members of their caucus by the Democratic leaders are the price of aspiring to be a genuinely national party. The congressional Republicans are unified, all right. But they are reduced to an ideological and regional faction and seem intent on “purifying” the party even more—the forces that backed Conservative Party candidate Doug Hoffman against Democrat Bill Owens in upstate New York vow to run conservative challengers in GOP primaries against alleged moderate apostates. If the Democrats are eventually to increase their majority, the only place to increase it is in districts that are currently red, or at best “purple.” Thus the paradox that a larger Democratic majority, at least in the House, will likely make for a somewhat more conservative one. The Blue Dogs will long be with us.

—November 5, 2009

This Issue

December 3, 2009

-

1

This could change next year. The GOP is targeting both House incumbents, and one of them, Paul Hodes, is seeking the Senate seat to be vacated by retiring Republican Judd Gregg, in what is judged to be a highly competitive race. ↩

-

2

In conservative Utah, Salt Lake City itself is a Democratic stronghold. ↩

-

3

See Alex Isenstadt, “The Dems Who Bucked Obama,” Politico, February 2, 2009. ↩

-

4

See Glenn Thrush, “Cooper: Obama Staff Encouraged Defiance of Pelosi,” Politico, February 3, 2009. ↩

-

5

For a fascinating and useful interactive map of presidential election results by congressional district, go to innovation.cq.com/atlas/district_08. ↩

-

6

See Patrick O’Connor, “House Energy and Commerce Committee Approves Health Care,” Politico, July 31, 2009. ↩

-

7

See my blog, “How Nervous Should Those Blue Dogs Be?,” www.guardian.co.uk, July 29, 2009. ↩