When we first started looking through microscopes

a cold fear blew and it’s still blowing.

Life hitherto had been frantic enough

in all its shapes and dimensions.

Which is why it created small-scale creatures,

assorted tiny worms and flies,

but at least the naked human eye

could see them.

But then suddenly beneath the glass,

foreign to a fault

and so petite,

that what they occupy in space

can only charitably be called a spot.

The glass doesn’t even touch them,

they double and triple unobstructed,

with room to spare, willy-nilly.

To say they’re many isn’t saying much.

The stronger the microscope

the more exactly, avidly they’re multiplied.

They don’t even have decent innards.

They don’t know gender, childhood, age.

They may not even know they are—or aren’t.

Still they decide our life and death.

Some freeze in momentary stasis,

although we don’t know what their moment is.

Since they’re so minuscule themselves,

their duration may be

pulverized accordingly.

A windborne speck of dust is a meteor

from deepest space,

a fingerprint is a farflung labyrinth

where they may gather

for their mute parades,

their blind iliads and upanishads.

I’ve wanted to write about them for a long while,

but it’s a tricky subject,

always put off for later

and perhaps worthy of a better poet,

even more stunned by the world than I.

But time is short. I write.

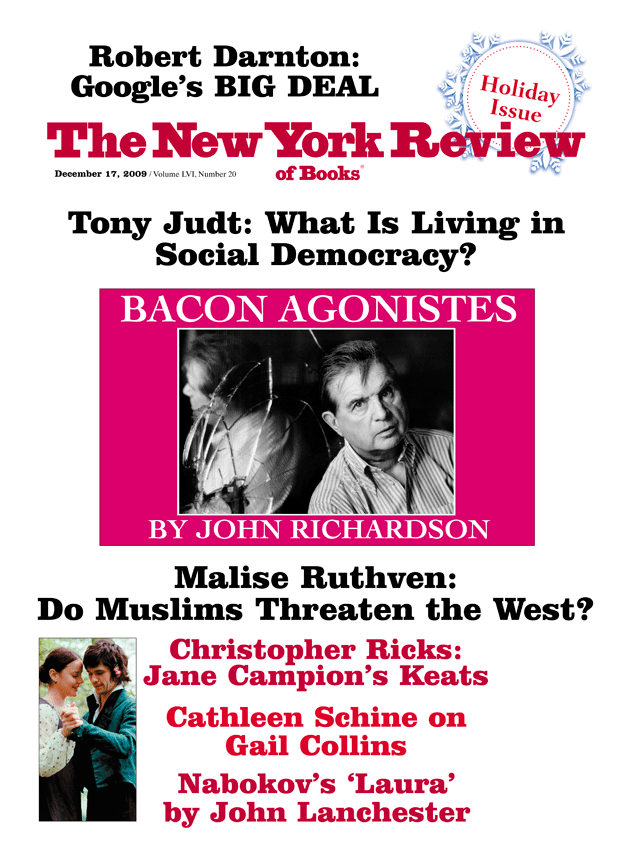

This Issue

December 17, 2009