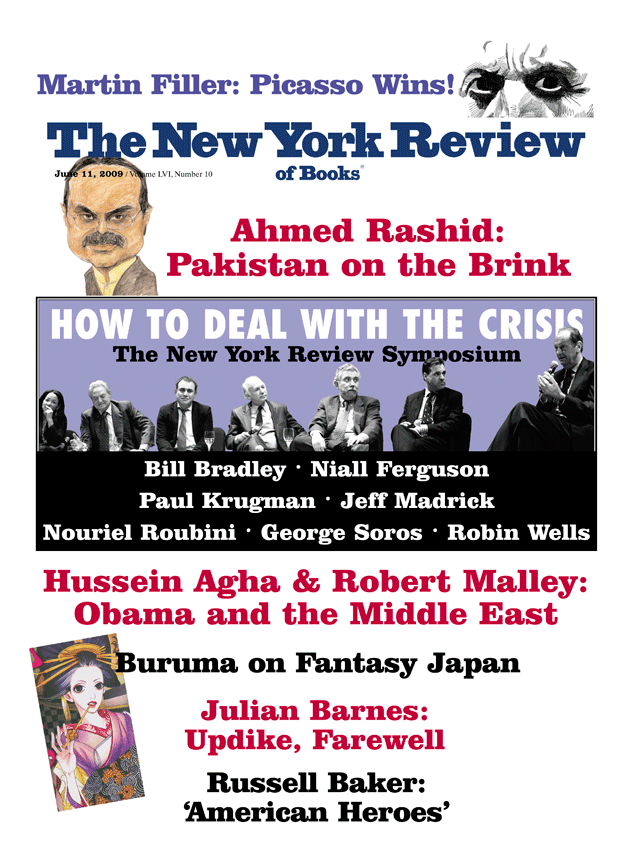

Anno Moyoco/Una Knox/Vancouver Art Gallery

The cover illustration of Anno Moyoco’s manga Sakuran, set in a red-light district during the Edo period and published by Kodansha in 2003; from ‘KRAZY! The Delirious World of Anime + Manga + Video Games,’ an exhibition organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery and on view at the Japan Society, New York City, through June 14, 2009

1.

Murders are relatively rare in Japan, but when they occur they tend to be frenzied: a young man—“sick and tired of life”—plowing into a crowd of Tokyo shoppers in a hired two-ton truck, before knifing seven people to death; an eleven-year-old schoolgirl slashing her twelve-year-old friend after a row over a message posted on the Internet.

In November 2008, Koizumi Takeshi, an unemployed man of forty-six, dressed as a parcel delivery man, turned up at the home of Yamaguchi Takehiko, a former Health Ministry vice-minister. The ex-bureaucrat, who was forced to resign his post after the government lost millions of pension records, came to the door wearing his wife’s slippers. Soon both Yamaguchi and his wife lay sprawled in the hall, one on top of the other, after being stabbed multiple times in the chest. Later that same day, the wife of another Health Ministry bureaucrat was wounded by the same man (her husband was not at home).

The case was written about extensively in the Japanese press. The scandal about the lost pension records was cited as the most likely motive for the killings. Clearly they had to be extreme symptoms of popular rage at government incompetence in a time of economic distress.

In fact, the killer turned out to have been enraged by something quite different. Many years ago, when he was still a young boy, Koizumi’s pet dog had been taken to the pound by his father to be euthanized, apparently for disturbing the neighbors with its frequent barking. The sad event was hardly the responsibility of the vice-minister of health and welfare, but Koizumi explained in an e-mail message that his murder “was revenge for the killing by a healthcare center of my family thirty-four years ago.”

That the Japanese press instantly linked the murders to the economic crisis reveals the jumpiness of the public mood in Japan. The statistics are indeed grim: industrial output fell by 9.6 percent last December, unemployment “soared” to 4.4 percent, by January exports fell by 46 percent, and the economy might contract by as much as 5.8 percent this year.

Not that you notice many of the effects of this in the tonier parts of Tokyo. On the first day of a visit, in early January, I was taken to a Parisian-style café in fashionable Omote Sando, where a café au lait costs more than $10. At the next table was a smartly dressed middle-aged man fussing over his pet Pomeranian, whose furry head, adorned with a denim cap, emerged from a Louis Vuitton handbag. Nearby was another customer who had laid out a little carpet lest her perfectly groomed cocker spaniel get cold paws. It did not look as though these people were hurting.

A few miles east of that café, however, not far from the imperial palace, you could see plenty of people who were. In Hibiya Park, opposite the old Daiichi Insurance building where General Mac- Arthur established his headquarters during the occupation years, homeless workers had created a kind of tent village over the New Year holidays. Many of them were former employees on temporary contracts, who had lived in company housing. Now all they had was some blue plastic sheeting to put up over their heads, until they were moved out of the park into hostels set up for the homeless. This being Japan, civil niceties were still observed: shoes fastidiously placed outside the tents, laundry flapping from taut lines, garbage put out in neat little piles.

Japan is famous for its so-called “lifetime employment system,” repaying employees for their corporate loyalty by keeping them on even in bad times. In fact, by no means all Japanese companies ever offered such benefits, and one third of the workforce is now on temporary contracts. Temporary job-hopping became popular after Japan’s economic bubble burst in the early 1990s, but really took off after new labor laws in 1999 and 2004 made it possible for manufacturers, as well as other companies, to take on large numbers of temporary workers. It offered more freedom to young people who had no desire for a lifetime of corporate drudgery, and was a cheap way for companies to recoup some of their losses.

Another common sight these days in public parks, as well as libraries, are men in dark business suits quietly reading the papers, for hours on end. These are the middle-ranking corporate men who cannot face the humiliation of letting family and neighbors know that their companies have no more use for them. So they pretend to go to work, even after being laid off. Economic misery and rising unemployment are hitting older people especially hard. One of the more chilling bits of news to emerge in recent days is that Japanese over sixty are the fastest-growing age group among the roughly 33,000 suicides a year (36.6 percent). A contraction in pension schemes is said to be one of the reasons. Men in their fifties are the second-largest age group (21 percent).

Advertisement

Skid rows in Tokyo and Osaka used to be poor but lively. Large numbers of young men from all over Japan would gather in Tokyo’s Sanya district or Osaka’s Kamagasaki to compete for daily jobs on construction sites or in factories, doled out by labor contractors affiliated with organized crime. No longer. I walked around both districts this winter. The drab streets looked even drabber, but also emptier. Flophouses offering rooms for roughly $10 a night were not doing much business. The average age of the men (and a few women) listlessly hanging around seemed to be well over fifty. They were warming themselves around bonfires in tin drums, drinking cheap saké. Some sang songs or told stories, and some just sat there cursing. Jobs have dried up, even for day laborers.

2.

Art in bad times is often escapist. Japan is no exception. The most popular entertainments are the cartoonlike manga comics, which cater to all manner of specialized tastes: teenage romance, baseball heroics, science fiction, kinky sex, or nationalist fantasies (kamikaze derring-do and the like). Prime Minister Aso Taro is a fan of comic books. He keeps them in the back of his official car. One way of boosting Japanese exports, he recently suggested, is to exploit the international appetite for Japanese popular culture, not just manga, but also animation movies ( anime ) and pop music (J-pop). Now 2 percent of all exports, such “soft power” should grow, in government projections, to 18 percent in ten years, creating half a million jobs.

A Japanese movie, entitled Departures, about a cello-playing undertaker, won this year’s Oscar for best foreign film. But the film that best catches Japan’s current mood is called Tokyo Sonata.1 The hero, if that is the right word, named Sasaki, is one of those salarymen in the middle ranks of a middle-ranking company who gets laid off because there is no need for him anymore. Sasaki (superbly acted by Kagawa Teruyuki) is the kind of drudge who would have been taken care of in better days. When he is asked by a much younger colleague what particular skills he might have that should merit continued employment at the company, he is genuinely perplexed. That was never part of the deal. There was nothing particular about him. That was the point of being a devoted salaryman: you didn’t stick out, either through gross incompetence or by displaying any notable skill.

Like so many of his real-life counterparts, Sasaki prefers to spend his days on a park bench rather than tell his family about his lost job. His loyal wife, Megumi (Koizumi Kyoko), figures it out in the end, but pretends not to know. The sons, estranged from their parents, as well as everyone else, it seems, escape into worlds of their own: one into piano music, for which he has an extraordinary gift, the other into the US Army, to fight in Iraq, just to do something meaningful—a complete fantasy, of course. There are hardly any Japanese in the US Army, but Kurosawa Kiyoshi, the director, is given to flights of fancy; most of his films are supernatural horror pictures.

In the end, the various strands of what started as a beautifully contrived, utterly realistic story veer into pure melodrama: the wife goes off with a crazed robber, driven to crime by failing at everything else; the husband flees from his new job as a cleaner in a shopping mall; and the piano-playing son turns out to be a musical genius. The sudden shift in tone is distinctly strange, but there is a reason for this. Melodramatic fantasy, as depicted in manga comics and animation films, seems to be the only way out of social and economic dead ends.

Kurosawa’s film tells us a great deal about contemporary Japan without being overtly political (except, perhaps, in the fantastical reference to the Iraq war). The alienation of the children, the almost catatonic state of family relations, the retreat into private worlds—these phenomena are all written about in the Japanese press almost daily. The word for young people who resist all communication except with their laptops, or who become monomaniacally obsessed with a (usually electronic) game or some abstruse hobby, is otaku. An entire culture has evolved around otaku, in the visual arts, but also in the most popular form of fiction writing, stories of teenage self-obsession distributed through mobile phones. Text messaging is the favored form of communication among young Japanese. You see groups of friends sitting around coffee shop tables, each thumbing his or her own phone.

Advertisement

Another popular otaku pastime, which has sublimated (and sometimes not so sublimated) erotic overtones, is costume play, or cosplay in Japanese-English. Young girls and boys dress up as characters from their favorite manga and get together to pose for pictures, taken on their mobile phones. As with manga, adults have shown a not always wholesome interest in this too. There are cosplay bars all over town (some of them brothels), cosplay DVDs, cosplay stores, and cosplay magazines.

In the east of Tokyo lies an area called Akihabara, a kind of souk for electronic gear—computers, video games, mobile phones, porno DVDs. “Akiba,” in current slang, is the Mecca of otaku culture. The fact that Kato Tomohiro, the young man who drove into the crowd of shoppers in a two-ton truck before wielding his thirteen-inch survival knife, did so in Akihabara was no coincidence. He was known to be an “Akiba guy,” a typical otaku. One of the few friends he had in life, perhaps the only one, a man who worked with him in a temporary factory job, said that Kato’s apartment was strewn with animation films and game DVDs. But Kato got tired of virtual women. He told his friend that he wanted the real thing, he wanted “girls with cute voices like anime characters…who look good in cosplay costumes.”2 And when that didn’t work out, he went for the kill.

To claim that Kato Tomohiro is typical of young Japanese today would be a gross exaggeration. His is an extreme case. But the lapse into solipsism among young Japanese is too common to dismiss as just another fad. There is in this behavior a link, I believe, with the unemployed salarymen reading their papers all day on park benches. It is a deliberate rejection of reality, a flight into make-believe. And this, in turn, is echoed in the behavior of the Japanese government itself. One of the most commonly cited reasons for the depth and length of the economic slump that started in the 1990s was the refusal of the government to acknowledge the disastrous state of Japanese banks, as though problems would go away if everyone pretended that things were all right.

Something has changed, however, in Japan, something that is reflected in the economic crisis, in the alienation of the otaku young, in the changing suicide statistics, in endless anxious articles in newspapers and magazines, in the nervousness about Japan’s status in the world and China’s increasing power. The collapse of the deal with the loyal company man, who thought he was safe as long as he kept his head down, is part of a deeper problem. The whole architecture of Japanese society, constructed from the wreckage of a disastrous world war, is crumbling.

3.

In 1960, after widespread demonstrations against the renewal of the US–Japan security treaty had led to the resignation of Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, his successor, Ikeda Hayato, announced a government plan to double everyone’s income through high-speed growth. Enriching the population under the paternalistic rule of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was a deliberate attempt to deflect political energies into economic well-being. The middle class was offered a deal: material wealth in exchange for political acquiescence, a virtual one-party state with no more protests, and the dutiful army of salarymen would be taken care of. Labor unions had been pretty much tamed, sometimes with the strong-arm help of gangsters. And Japanese pacifism was guaranteed by a constitution, written by Americans in 1946, which banned the use of armed force. Responsibility for national security was handed over to the US, which had (and still has) military bases all over the Japanese archipelago.

This system, put in place in 1955, when the LDP was formed, and cemented in 1960, suited the Japanese political and business elite, who could now concentrate on industrial expansion. It suited most Japanese, who wanted nothing more to do with war. Like a reformed alcoholic, many Japanese feared that even one little sip of military action would lead to another bender. And it suited the US, which wanted Japan to be a reliable bastion against communism. So CIA money was funneled into the already well-stocked coffers of the LDP for several decades, to make sure all signs of leftism were kept at bay; rather like what happened in Italy, where the Christian Democrats benefited from a similar arrangement.

When the US and its allies occupied Japan after the war, one of the main goals was to establish a stable democracy. To the eternal credit of General MacArthur’s administration and Japanese democrats, they succeeded. But in the LDP state, democracy began to suffer from lack of use, as it were. The left was both marginalized and, briefly, radicalized. As happened in Italy and Germany, the fragments of the 1960s protest generation exploded in acts of mindless violence in the 1970s: airline hijackings, purges of “traitors,” murder sprees on behalf of Palestinian liberation, and other revolutionary causes.

The electoral system, skewed to favor conservative rural constituencies, made it hard for more liberal parties to challenge the supremacy of the LDP, which was soon corrupted by the vast amounts of money slushing through the system. The ruling party, in fact a huge pork-barrel operation, became increasingly gummed up by a congeries of factions led in recent years by members of political dynasties going back at least three generations. Prime Minister Aso, for example, is the grandson of Yoshida Shigeru, prime minister in 1946, and one of the chief architects of the LDP state. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, a recent predecessor, was Kishi’s grandson.

The postwar deal (often called the “Yoshida deal,” or the “1955 system”) had another consequence, which is now becoming painfully obvious: it marginalized Japan as an international player. While China and even India receive enormous attention as rising powers, Japan, which still has the second-biggest economy in the world, is seldom in the news, except when some hack politician says something silly about the role of women or the last world war. No Japanese political thinker has made any impact in the West, or indeed anywhere else. Intellectually and politically, Japan seems to exist in a peculiar bubble of its own.

It did not look this way twenty years ago, when all kinds of intelligent people were warning us about Japan’s imminent dominance of the world. The “Japan model,” of brilliant bureaucrats steering huge business and industrial conglomerates toward ever greater victories on the world markets, was seen as either a great danger or something to emulate, or both. Pundits declared that “soft” economic power was much more important than the “hard” military kind. Even if the slump of the 1990s did not exactly destroy the “Japan model,” with its fuzzy borders between private and public enterprise, it certainly showed up its vulnerabilities. And the recent collapse of the “American model” has caused even greater havoc, because of Japan’s sacrifice of domestic consumers’ interests to the demands of its export industries, now in search of customers.

The ups and downs of the Japanese economy, however, don’t explain the country’s relative isolation and political sclerosis. Of all people, the man who saw this coming was Kishi Nobusuke, the ultra-nationalist wartime minister of armaments, arrested in 1945 as a war criminal, only to be released from prison in 1948, when fiercely anti-Communist politicians were suddenly in demand. He was the prime minister who provoked mass demonstrations when he signed a new security treaty with the US in 1960. Kishi was opposed to the “peace constitution” from the beginning. Handing over responsibility for national security to a foreign power, he said, was a humiliating abdication of national sovereignty, rather like the unequal treaties in colonial times. This view is still shared by a significant number of Japanese conservatives. What Kishi wanted was a system in which two more or less conservative parties would hold each other in check. A one-party state, bent on nothing but economic gain, would not only lead to the corruption of power, but put Japan on the sidelines of all but business affairs.

Unprepossessing as Kishi was, he had a real point. Under pressure from the US, which soon regretted having promoted pacifism, Japan created the so-called Self-Defense Forces. But the SDF still couldn’t contribute much to international conflicts except for the odd engineering project. Even for Japanese engaged in patrolling duties, as several hundred now are off the coast of Somalia, the spirit of the constitution had to be compromised. Some, both in and outside Japan, might consider barriers to military action to be a very good thing. But the lack of consensus over the continuously fudged constitution and the odd status of being a kind of vassal state to the US have created anxieties, resentments, and frustrations, which have a depressing effect on political debates in Japan and on Japan’s relations with the outside world.

A glimpse of this can be seen in Kurosawa’s movie Tokyo Sonata. Boredom with Japan’s lack of international status and the emptiness of its pursuit of materialism is why Sasaki’s elder son decides to go to Iraq with the US Army. He craves an ideal, something to fight for.3 Perhaps this is what the novelist Murakami Ryu meant when he said, “We have everything in Japan except hope.”4 The same frustration explains the popularity among young Japanese of comic books celebrating Japanese heroism during World War II, and why the rise of China is causing such fear, as well as resentment, especially when Chinese officials use history as a tool to stoke nationalism or to extract political or economic concessions from Japan.

A national debate on Japan’s constitution is long overdue. The conservative Yomiuri newspaper tried to promote this idea in its pages after the 1991 Gulf War, when Japan was criticized for not offering anything but a financial contribution. The proposal was not radical, but simply to make Japan’s right to self-defense explicit. Ozawa Ichiro, a former LDP politician who started his own opposition party in 1993 and more recently, until his resignation in May, led the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), went one step further and argued that Japanese forces should be able to take part in international combat missions under the auspices of the UN. He also wants all US forces, except the Seventh Fleet, to vacate their Japanese bases.

The debate stalled, however. Instead, often provoked by unguarded statements by right-wing politicians, there are endless polemics about history, not so much by historians, which would be proper, but by politicians, journalists, and commentators with political agendas. As long as defenders of the “peace constitution” bring up Japan’s former militarism as a reason to oppose constitutional change, conservatives will argue that Japan did nothing wrong, indeed, that Japan fought a noble war to liberate Asia from Western imperialism.

Such statements by officials are usually followed by swift resignations from public office, especially when they reach the foreign press, causing yet more resentment among the nationalists. The latest spat of this kind occurred last year, when Air Self-Defense Force Chief of Staff General Tamogami Toshio wrote an essay depicting Japan as a wartime victim, dragged into the Sino-Japanese conflict by Chiang Kai-shek and tricked by the US into waging the Pacific war. Japanese journals are still arguing for one side or the other, depending on their political views.

In this respect, Japan is trapped in the 1950s, bogged down in arguments that should have been settled decades ago. Without settling them, however, it will be difficult for Japan to be trusted by its Asian neighbors and have a diplomatic influence commensurate with its economic weight. China will continue to gain influence, probably at Japan’s expense. Meanwhile, the US armed forces are still in Japan, financed to a large extent by the Japanese themselves, even as many people resent their continued presence.

The biggest change since the LDP state was established is that the government can no longer keep up its side of the bargain with the Japanese middle class: the slump took care of that. This has not yet had the effect of repoliticizing the middle class; there are no big demonstrations, at least not yet, nothing except an anxious waiting for worse to come.5 The election of Barack Obama, which electrified Europeans, fascinated Japanese too. But the main worry in official circles upon the Democrats’ great victory was that the new president might care more about China than about Japan.

4.

Although not nearly as cosmopolitan as London, New York, or even Hong Kong, Tokyo is more cosmopolitan than ever before. (It has more Michelin-star-rated restaurants than even Paris.) Large numbers of young Chinese and other Asians are flocking to Japan to study or to work in entertainment, stores, factories, and business. In Tokyo Sonata, just as Sasaki is told that he is no longer needed, we are shown a group of eager young Chinese being interviewed. They seem hungrier, sharper, and altogether more lively than the tired Japanese salarymen.

Few of these foreigners are citizens. And there is great resistance to granting them citizenship. Brazilian and Peruvian workers of Japanese descent are even being offered financial incentives for going back to their countries, never to return. Exceptions are sometimes made for Brazilian soccer players, enlisted to strengthen the national team, or Sumo wrestlers. Both current grand champions in this ancient Japanese national sport now happen to be Mongolians—another reason for some Japanese to feel humiliated by gutsier, more powerful foreigners.6 Yet with plunging Japanese birthrates, the foreigners will be badly needed, and not just to bolster the Sumo stables. In 2025, nearly 30 percent of the Japanese population will be elderly.7

The sense of national malaise has inspired a lot of fanciful and nationalistic rhetoric, which often takes the place of political debate. Prime Minister Aso’s assertion last January that Japanese culture, with its superior work ethic, in contrast to Judeo-Christian sloth, will lead the world out of its present economic crisis is unusually inane, but alas not untypical. Most Japanese, however, agree that what is most needed to reenergize the nation is political change. Only an end to LDP domination will break the already crumbling mold of the postwar Japanese state, overly dependent on the US abroad, corrupt and sclerotic in its domestic politics. Japanese democracy needs a fresh start, with a change of government. This happened briefly in 1993, when three non-LDP prime ministers in quick succession led coalition governments. But by 1996, the LDP was again in control, not quite as firmly as before, but still dominant.

The opposition figure with the most interesting ideas in the 1990s was Ozawa Ichiro. His book Blueprint for a New Japan8 was a serious intellectual attempt to break with the ancien régime. Aside from a change in the constitution to restore Japan’s responsibility for its own defense, his main proposals included new electoral rules to shift the balance toward urban middle-class voters, with less power to bureaucrats and more to elected politicians. In short, he advocated a more democratic, more accountable multiparty system to replace the factional, pork-barrel politics of the LDP state.

I thought then that perhaps Ozawa’s time had come. In fact, I was too optimistic. Like John McCain, Ozawa always had the reputation of being a maverick. But mavericks, especially high-handed mavericks, are not popular in Japanese politics. Smooth backroom dealers, who avoid making enemies, are generally more success-ful. They know how to suffer fools gladly, an essential attribute that Ozawa utterly lacks. He has a habit of burn- ing his boats and alienating potential allies.

With the economic crisis biting and the LDP’s standing in the polls low, Ozawa was given a second and probably last chance. Although only sixty-six, not that old for a Japanese leader, he was not in good health. Earlier this year, he was still well ahead of Prime Minister Aso in polls, and his Democratic Party of Japan easily would have won in a general election. But in March, his chief secretary, Okubo Takanori, was arrested for taking illegal donations from a construction firm. LDP politicians allegedly received money from the same source, but the opposition leader’s standing was based on the fact that he would be different. On May 11, with opinion polls turning rapidly against him, Ozawa announced his resignation as leader of the DPJ.

Even if the DPJ were to win the next election, which must take place by September, the problems will be huge, quite apart from the economic mess. There is, as yet, no clear political ideology to hold the various factions in the DPJ together. Some DPJ politicians were socialists, others were liberal defectors from the LDP. One of the party’s potential coalition partners, a pacifist Buddhist party called the New Komeito, is opposed to plans to revise the “peace constitution.”

Still, an opposition win would be a boost to Japanese democracy. The end of the LDP state might finally lift Japan out of the traumas of war and occupation. Japanese voters might regain a sense that they matter, that the system works. A constitutional debate might break the deadlock between pacifists and conservatives. History might be faced honestly, and not just used as a stick to beat up political opponents with. Might, might, might… Yet these possibilities are important. For Asia, faced with the rise of an autocratic, confident China, badly needs a Japan it can trust. But Japan must learn to trust itself again first.

—May 12, 2009

-

1

Released in New York and select cities in March, and in the rest of the country later this year. ↩

-

2

Reported in Shukan Post, a popular weekly magazine, June 16, 2008. ↩

-

3

When the left was still strong, pacifism itself was a national ideal, pursued with more or less self-righteousness. But with the worldwide collapse of socialism, this too evaporated. ↩

-

4

Yomiuri Shimbun, January 1, 2009. ↩

-

5

The once powerful Japanese Communist Party, garnering most of its votes from the working class, is growing again. ↩

-

6

Japan’s victory in this year’s World Baseball Classic caused almost hysterical joy in Japan, even as it was more or less ignored in the US, which lost to Japan in the semifinals. ↩

-

7

See Michael Elliott and Coco Masters, “Ozawa: The Man Who Wants to Save Japan,” Time Asia, March 23, 2009, available at www.time.com. ↩

-

8

Kodansha International, 1994; see [my review](/articles/archives/1994/may/12/japan-against-itself/) in these pages, May 12, 1994. ↩