It’s chastening to think back to the predictions being made last summer about health care reform, and the assumptions that were widely shared in Washington at the time (certainly by me). Reform would face challenges, and it would never go as far or be as comprehensive as liberals wanted it to be. But some new law would pass by Thanksgiving or sooner. The stars that had defied alignment since the early attempts to pass national health legislation under Teddy Roosevelt were now fully in place.

Something may yet pass. But the price of reform has escalated considerably since last June. Barack Obama has lost about fifteen points in approval ratings, hovering at or just below 50 percent. In all polls, independent voters are more disapproving of Obama and of the Democrats’ health legislation than not. Citizens quite reasonably asked themselves why Obama and the Democrats have been spending so much time on health care while unemployment soared to 10 percent. Republicans have acquired momentum from the public opposition and now stand to make significant gains in the mid-term elections. The Democrats lost their supposedly “bullet-proof” Senate supermajority and, according to polls, came to look to many average voters as if they couldn’t govern. And even if health reform does pass, its putative benefits—insuring 30 million more people, lowering premiums, controlling costs—won’t go into effect until 2014. And the risk is still substantial that the effort will end in defeat.

What happened? It’s still too early to be sure, but broadly speaking, we can divide the chaotic details of the past several months into two categories: the political and the institutional. Obama and his administration certainly made their share of political errors, many stemming from the President’s having learned the wrong lessons from history, specifically the 1994 defeat of the Clinton effort. Whereas Bill and Hillary Clinton presented a plan to Congress that gave the key legislators comparatively little opportunity to collaborate on health policy or to take credit for it, Obama did the opposite to a fault. He gave the House and Senate too much time and leeway to develop their own plans. The administration finally announced its own reform principles on February 22, long after both houses of Congress had passed different versions of a bill.

There were arguably even bigger miscalculations than that. In my view, attempting comprehensive health care reform during Obama’s first year with a very bad (and weakening) economy was asking a lot of the American people. The 2008 election was a rejection of conservatism, but it was not an embrace of liberalism. Any chance of a new liberal era, I wrote here in 2008, “would depend on what President Obama and the congressional Democrats did with their power.”1 I believed they should first prove themselves competent economic stewards; having gained a solid majority of the public’s trust on that most basic issue (and set themselves in sympathetic contrast to the GOP on it), the Democrats might have then convinced voters to follow them down the path of health care reform and new environmental rules, among other urgent matters.2

In some ways the larger impediments to reform have been institutional. Congress has not passed a piece of major progressive social legislation for many years. One could call the creation of Medicare Part D in 2003 a “landmark” in that it established a new entitlement—prescription drugs—thus expanding Medicare considerably. But it also greatly increased the importance of the private sector in Medicare, with consequences that are still playing out. For example, privately offered fee-for-service plans, so-called Medicare Advantage plans, have expanded rapidly since 2003. And Republicans constructed the bill in such a way that the new coverage wasn’t paid for.

There are a few other serious accomplishments from the 1990s and 1980s—the expansion of the earned income tax credit of 1993, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Simpson-Mazzoli immigration act of 1986, and perhaps others. But for the really major changes, which were made over a fairly short period, we have to go back farther: the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts (1970 and 1972, respectively); Medicare and Medicaid (1965); the Voting Rights Act (the same year); the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One important question raised by watching this process has been: Is Congress capable of passing major, progressive domestic legislation anymore? Even if the answer in this case turns out to be yes by a few votes, by means of the reconciliation process, the question deserves our attention. Liberals are sitting on several important pieces of legislation they’d like to see passed, on the environment, labor, energy, and climate, to name only a few. Can Congress confront these issues?

Advertisement

It’s true that Congress is simply more conservative in general than it once was—it has fewer members inclined to back broad domestic legislation. In addition, however, two crushing institutional obstacles have arisen since the 1960s and the 1970s. One concerns procedural rules, especially the Senate’s cloture rule requiring sixty votes to end debate and bring any matter to the floor for a final vote, avoiding a dreaded filibuster. Demands for cloture votes were rare until the mid-1970s. They increased rapidly over the decades and then doubled after the GOP lost the Senate in 2006. This matter has begun to receive attention in the press (and will be the subject of a future piece here).

The other obstacle has to do with the power of money in politics: through lobbying, advertising, and campaign contributions. This subject is less often discussed. It’s an old story now,3 and people just more or less accept it as the state of things. Political reporters focus on the day-to-day political process. So the money story is usually left to the dwindling investigative staffs of news organizations—and, in our age, to a small number of Web sites that track donations and influence. These sites do an excellent job, but they aren’t well known to the larger public, and lobbies or large donors make the news only when something deeply suspicious occurs—when the press can identify a quid pro quo. And yet, influence only rarely works that way. Politicians and lobbyists both know better than to speak to each other about votes in exchange for financial support. Direct causation between Contribution A and Vote B can almost never be established.

There have, though, been some instances where the influence of powerful corporate lobbies has been clear. They won obvious victories in defeating amendments on the floor or in committee on issues such as drug reimportation from abroad, bringing generic drugs to market more quickly, and closing the so-called Medicare prescription drug “donut hole” (by which Medicare covers prescription costs up to $2,700 and over $6,154 but not in between). As I will discuss later, much of this action reflected a deal the administration made with the powerful pharmaceutical lobby, “Big Pharma,” whose chief concerns include these matters and the issue of allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices, which the lobby opposes. Since February 22, the administration has backed away from this deal, thus completely closing the donut hole.

Beyond these and a few other cases, the direct effects of the large interests and their money can be difficult to discern. But the dollar figures are staggering. The lobbyists have been at this for a long time, so we must assume that they know what they’re doing, and that they are spending all that money for a reason.

In all, federal lobbyists and their clients spent more than $3.47 billion last year. That is an all-time high, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, whose executive director notes dryly that lobbying is one business that appears to be “recession proof.”4 The center tracks spending by thirteen broad categories of economic activity. The biggest-spending sector was something it calls “miscellaneous business,” including retail and manufacturing, which spent $558 million last year. The health sector finished a close second at $544 million, an increase of about 12 percent over its 2008 total. When looking beyond those sectors to individual industries, the center found that the “pharmaceutical and health products” industry was the largest-spending industry last year, putting $267 million into its lobbying efforts, which stands as the largest amount ever spent by a single industry in one year. Those efforts include payments to individual lobbyists who talk to legislators, send them information, and get in touch with others who may influence them. The center notes that last year’s fourth quarter, from September to December 2009, was the first quarter in history in which all spending for lobbying topped $900 million; it reached $955 million, a 16 percent increase over the fourth quarter of 2008.

Common Cause issued a report last June that got much attention by announcing that health interests were spending $1.4 million a day lobbying Congress.5 But that number surely grew over the course of last year. That fourth quarter, after all, was when both the House and Senate finally passed their bills. The Senate was in session for fifty-five days and the House for forty-one, averaging out to forty- eight working congressional days. The $955 million cited by the Center for Responsive Politics for the fourth quarter of 2009 was for lobbying in all categories, not just health care. It amounts to almost exactly $20 million a day. Clearly a considerable chunk of that was spent lobbying the two houses on the most important legislation before them at the time.

Advertisement

The National Journal, through its Web site Under the Influence, collects similar data. It has tracked the money laid out by the twenty-five highest-spending organizations lobbying about health care, among them major insurance firms, business lobbies, and various medical trade associations. These numbers are therefore smaller but still enormous, amounting to a combined total of over $288 million in 2009. The biggest spender was the US Chamber of Commerce, a leading opponent of reform, which spent $123 million in 2009. Undoubtedly not all of that was on health care, but the Chamber did spend more than half that amount, or a staggering $71 million, in the fourth quarter of 2009 alone. On March 10, the Associated Press reported that the Chamber was coordinating a multimillion-dollar ad campaign by insurance companies to stop health care reform. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the most powerful pharmaceutical lobbying organization, spent $26 million. The AARP spent $21 million; the American Medical Assocation, $20 million. Some conspicuous participants in the debate spent lower figures—America’s Health Insurance Plans, or AHIP, the best-known insurers’ lobby, spent $8.85 million last year. (Some individual insurance companies have their own lobbies.) The Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association spent the same amount.

These National Journal figures remind us that not all lobbying is corporate and opposed to reform that will expand coverage. The AARP, for example, has been consistently in favor of such reform, even the proposed cuts to Medicare that the administration wants in order to finance its health program. The group’s support for reform caused tens of thousands of AARP members to quit, CBS reported last summer.6

Some of the smaller spenders in favor of reform have relatively narrow concerns. For example, in 2009, the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network spent more than $4 million to advance preventive measures against cancer, such as more money for early screening and antismoking programs. Labor unions, of course, supported reform, but their amounts spent on lobbying were piddling compared to those of the corporations. The AFL-CIO spent just $2.26 million, and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, $2.87 million. Generally speaking, all but a tiny portion of lobbying money was spent either opposing the reform legislation outright or bending it to reflect corporate goals.

In addition, it’s worth remembering that, apart from lobbying legislators, these organizations spend vast sums for television and radio advertising. Last month, The National Journal ‘s Peter H. Stone reported that AHIP solicited between $10 million and $20 million from six large insurers—Cigna, Aetna, Humana, Wellpoint, Kaiser Foundation Health Plans, and UnitedHealth Group—that was funneled to the Chamber of Commerce to underwrite television ads opposing reform by two business coalitions set up by the Chamber.7 (AHIP was critical of both houses’ bills, it said, because, among other reasons, costs would skyrocket, even though insurers stand to gain millions of new clients.) PhRMA, as part of its deal with the White House, agreed to spend $100 million on television ads in support of reform—$100 million that, as everyone involved surely knew, could as readily have been spent on anti-reform ads if the outcome of the negotiations over the legislation had been less to PhRMA’s liking.

At one point last year, more than 3,300 people were registered as lobbyists on health care. That’s six for every member of Congress, House and Senate combined. Even the defense industry, according to Bloomberg News, had only two for every member.8 “We hear from lobbyists all the time,” said Representative Frank Pallone, a New Jersey Democrat who heads the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Health Subcommittee. Just what they say is seldom made public, but some accounts suggest that lobbyists have mastered the art of explaining to lawmakers why their position serves the common good, and the best ones are invariably well versed in the arcana of their particular policy concerns; lawmakers sometimes turn to them for guidance on the possible impact of a certain provision in a bill; and lobbyists may suggest measures they want incorporated in a bill or eliminated from it. We gather that, with few exceptions, they make many of the same arguments against the reform legislation that we hear from members of the Republican caucus.

About one in ten of those 3,300 lobbyists was a former government staffer or member of Congress, according to The Washington Post.9 Nearly half of the 350 or so former governmental employees turned lobbyists once worked on Capitol Hill for key legislators or committees—something that surely didn’t hurt their chances of getting access to Congress. The Post reported, for example:

A June 10 meeting between aides to [Max] Baucus, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, and health-care lobbyists included two former Baucus chiefs of staff: David Castagnetti, whose clients include PhRMA and America’s Health Insurance Plans, and Jeffrey A. Forbes, who represents PhRMA, Amgen, Genentech, Merck, and others. Castagnetti did not return a telephone call; Forbes declined to comment.

Also inside the closed committee hearing room that day was Richard Tarplin, a veteran of both the Department of Health and Human Services and the Senate, where he worked for Christopher J. Dodd (D-Conn.), one of the leaders in fashioning reform legislation this year. Tarplin now represents the American Medical Association as head of his own lobbying firm, Tarplin Strategies.

“For people like me who are on the outside and used to be on the inside, this is great, because there is a level of trust in these relationships, and I know the policy rationale that is required,” Tarplin said in explaining the benefits of having government experience.

PhRMA, at one point, employed forty-eight lobbying firms, in addition to its in-house operation, and had a total of 165 people lobbying for its positions—137 of whom had previous government experience, mostly in Congress, according to Paul Blumenthal of the watchdog group the Sunlight Foundation, which has done excellent work on these connections.10

We don’t know just what goes on at these meetings and probably will never know. Baucus posted his public schedule last year, so it was possible to see, as Blumenthal calculated, that he had held twenty meetings with health industry representatives, mostly drug makers and insurers, as well as twelve with representatives of public interest associations.

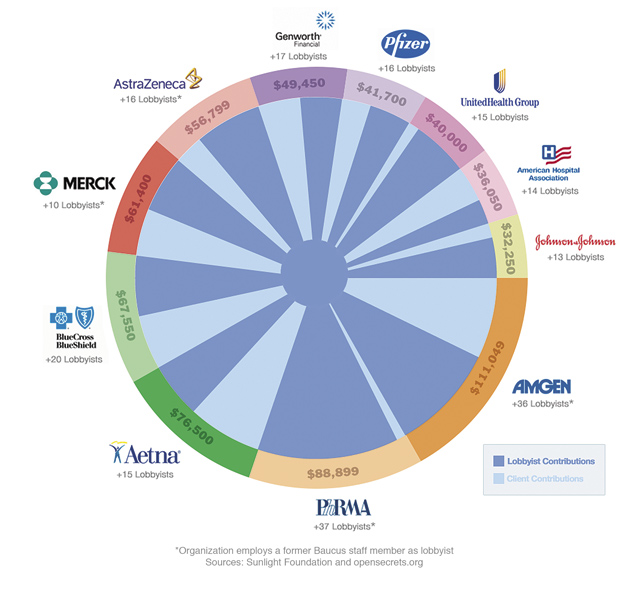

Baucus’s record raises the question of the other major category of corporate expenditure, campaign contributions, which are distinct from the rest of the money spent on lobbying. According to the invaluable opensecrets .org, Baucus has raised about $2 million from the health sector during the last five years, including during his 2008 reelection campaign (which is when contributions from key industries to senators tend to spike). In his low-cost state of Montana—population 968,000—he won reelection that year with 73 percent of the vote. (The illustration on page 12 gives a sampling of health sector contributions to Baucus between 2007 and 2009.)

Other members of Baucus’s “Gang of Six”—the three Democrats and three Republicans who negotiated the Senate Finance Committee bill last year—have received substantial campaign contributions from the health sector during the same five-year period: Republican Chuck Grassley took in $813,000, Democrat Kent Conrad $689,000, with each of the others closer to $400,000. Only Grassley faces reelection this year, and his seat is considered safe.

In all, organizations and individuals in the health industry have given $27.6 million in campaign contributions during 2009–2010, with 54 percent of that going to Democrats. About $9.6 million of that total has come from pharmaceutical interests, and $7.5 million from hospitals and nursing homes. Taken together, their contributions amount to roughly between $100,000 and $300,000 for most incumbent senators and for representatives, who all face reelection fights this year.

In 2008 Obama himself received $19.5 million from health-related donors, compared to John McCain’s $7.4 million. This should be compared with the $750 million he raised overall, and with the larger contributions he received from lawyers and from members of the communications and finance industries, among others.

What are the various members of the health industry getting in return for all these dollars? Some caution is in order here. On the big question, the private insurers won: if a health care bill is passed, it would contain no public option, no federal alternative that might compete with them. But many factors influence a member of Congress’s vote or position. Democratic Senator Ben Nelson of Nebraska, for example, has received hefty contributions from the health sector during the past five years, $759,000. But he’s also a fairly conservative senator from a very conservative state that happens also to be home to large insurance interests, including Mutual of Omaha. Is he doing their bidding, or is he protecting legitimate constituent interests, or is he merely following his own cautious political instincts? Or may he see all three coinciding in the public interest?

The clearest case of a powerful lobby winning its arguments behind closed doors on health issues, documented by the Sunlight Foundation’s Blumenthal, involved PhRMA’s deal with the White House.11 PhRMA’s chief interests are three. First, the group opposes allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices for seniors, which experts say would result in lower prices (and profits). The absence of such a provision in the 2003 Medicare bill caused many Democrats to oppose it. Second, it opposes drug “reimportation,” i.e., bringing in prescription drugs from other countries where prices are cheaper (opponents of reimportation cite concerns about safety and standards). Finally, PhRMA is concerned that Congress might hit it with the full cost, estimated at around $135 billion, of closing the so-called Medicare “donut hole.”

Obama campaigned in favor of closing the donut hole and allowing drug reimportation and Medicare drug price negotiation. Blumenthal documents how, step by step, PhRMA won on every point in negotiations both with White House officials and with Max Baucus. Several meetings during the spring and summer involved PhRMA CEO Billy Tauzin, a former member of Congress from Louisiana, Baucus or his staffers, and White House officials including Deputy Chief of Staff Jim Messina, who once worked for Baucus. Obama had dropped his campaign positions. The agreement was that nothing in the legislation would cost PhRMA more than $80 billion total (of which a reported $50 billion would go toward the donut hole problem).

As Baucus’s committee was preparing the final version of the health care bill last fall, Democrat Bill Nelson of Florida introduced a measure that would have closed the donut hole completely. The amendment failed 10–13, with Baucus and all Republicans opposing it, joined by Bob Menendez of New Jersey and Tom Carper of Delaware. Baucus and Carper both said at the time that they were standing by the White House’s deal with PhRMA. The White House was pressuring senators to keep to the deal. The three Democrats who voted with the Republicans also happened to be the top three Democratic recipients of PhRMA’s donations since 2003.

Then, as the full Senate debated amendments to the bill last December, North Dakota’s Byron Dorgan put forward a measure to allow drug reimportation. It received fifty-one votes, but it failed, because it was brought up under cloture rules requiring sixty votes. Dorgan’s amendment had been scheduled for a vote the previous week, but that vote was postponed. Then, several senators who had been on record as supporting reimportation switched their votes to “nay,” under pressure from Senate leaders and the White House, according to a report at the time in the Huffington Post, whose Ryan Grim followed the PhRMA deal closely. According to his report, when the roll was called and Connecticut’s Chris Dodd said “nay,” Vermont’s Bernie Sanders stage-whispered loudly enough to be heard in the press gallery: “Dodd?!”

Earlier last year, in the House, Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Henry Waxman had fought for a provision that would make so-called “biologic” drugs, which derive from living cells and are typically expensive, available in generic form in as little as five years, something PhRMA also opposed. Democrat Anna Eshoo of California, pairing with the committee’s ranking Republican, Joe Barton of Texas, introduced a substitute measure slowing that process to twelve years (Eshoo denied at the time that her amendment did that, but Waxman said it did). It passed 47–11 in committee. Eshoo has received $112,000 in pharmaceutical donations so far in 2009–2010, making it the industry that is most generous to her.

With the plan it released on February 22, the Obama administration took some steps to challenge these lobbies. The insurance industry dislikes the administration’s proposal for a federal rate-review board, a seven-member body led by the secretary of health and human services that would review rate increases. (The administration suggested the review board in response to a plan by California’s largest private insurer, Anthem, to hike the rate paid by some of its customers by 39 percent.) In addition, the administration has now proposed closing the donut hole completely. This can’t sit well with PhRMA, although it should be noted that, of the association’s big three issues, closing the donut hole would cost less than drug reimportation or a requirement to negotiate Medicare prices. Assuming the House and Senate finally decide to pass a health reform bill, it will be interesting to see whether these provisions make the cut.

In fairness, the bill’s many positive features should be recognized. It ends discrimination based on preexisting conditions and development of catastrophic illnesses. It eliminates price discrimination based on health status and offers subsidies for up to 30 million currently uninsured people. It establishes a host of other precedents concerning cost control and new services that would, taken together, still be a major, even astonishing, step forward. As big a victory as that would be, it will remain the case that it could have been a considerably better bill, in both providing medical care and controlling costs.

Whether it passes or not, the institutional pressures of big money have effectively and quietly deformed central parts of the bill and continue to loom over any attempt by Congress to write and pass major domestic legislation. Stronger financial regulation is now being resisted daily by Wall Street lobbies. It’s not a coincidence that there have been fewer and fewer pieces of large-scale economic and social legislation since big money has increasingly dominated politics from the 1980s on. The question that remains open is whether there is any effective way of revealing what is being bought and sold in Congress.

—March 11, 2010

This Issue

April 8, 2010

-

1

See “How Historic a Victory?,” The New York Review, December 18, 2008. ↩

-

2

The arguments for tackling health care immediately were twofold. Substantively, spiraling health care costs are a first-order issue. Politically, strike while the iron is hot—while Obama had the political capital and the Democrats had sixty votes in the Senate. ↩

-

3

One of the first journalistic investigations into all this was by Elizabeth Drew, in her Politics and Money: The New Road to Corruption (Macmillan, 1983). ↩

-

4

See “Federal Lobbying Climbs in 2009 as Lawmakers Execute Aggressive Congressional Agenda,” www.opensecrets.org, February 12, 2010. ↩

-

5

See “Legislating Under the Influence,” www.commoncause.org/healthcare2009. ↩

-

6

See “Thousands Quit AARP Over Health Reform,” www.cbsnews.com, August 17, 2009. The AARP says that it gains “hundreds of thousands” of members every month. ↩

-

7

See Peter H. Stone, “Health Insurers Funded Chamber Attack Ads,” undertheinfluence.nationaljournal.com, January 12, 2010. ↩

-

8

See Jonathan D. Salant and Lizzie O’Leary, “Six Lobbyists Per Lawmaker Work on Health Overhaul,” www.bloomberg.com, August 14, 2009. ↩

-

9

See Dan Eggen and Kimberly Kindy, “Familiar Players in Health Bill Lobbying,” The Washington Post, July 6, 2009. ↩

-

10

See Paul Blumenthal, “Researching and Writing the White House–PhRMA Deal,” blog.sunlightfoundation.com, February 16, 2010. ↩

-

11

See Paul Blumenthal, “The Legacy of Billy Tauzin: The White House–PhRMA Deal,” blog.sunlightfoundation.com, February 12, 2010. ↩