In the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville), a syncretic religion has arisen around a cult of General Charles de Gaulle. Its altars are decorated with Crosses of Lorraine and large “V’s” for victory. Its followers sing and dance to invoke Ngolo, which is also the word for power in the Bakongo language.

Although the canonization of De Gaulle now underway in France has utterly different outward trappings, it is no less authentic, as any tourist can see who contemplates the vast concrete Cross of Lorraine, built in 1980, that rises from a hilltop near De Gaulle’s country house at Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises (Haute-Marne), over a small museum and souvenir stand.

The change has been profound. Thirty years ago, when De Gaulle was president of France, almost half of French citizens regularly voted against him, and the most violent among them—the hard-core militants of French Algeria—were trying to kill him. Less murderous but still unreconciled were most of the left, the remaining partisans of the Vichy regime of 1940–1944, supporters of an integrated Europe along the lines preached by Jean Monnet, and believers in French membership in an Atlantic alliance headed by the United States.

Today De Gaulle’s popular image is being reconstructed in ways that do considerable violence to history. On the left, Regis Debray, former companion of Che Guevara, has written a paean to the general.1 François Mitterrand, who once referred to the Fifth Republic’s strong presidency as a “coup d’état permanent,” now exercises that office’s powers with recognizably Gaullian style and substance. Even Europeanists have begun claiming the general as their own. The Atlanticists have been left behind by events. Death has diminished the Vichy partisans. Those who remain, along with the unreconciled diehards of French Algeria, must be disappointed that their chief spokesman, National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen, never attacks the memory of De Gaulle. The craggy general is in danger of turning into a smooth plaster saint.

Jean Lacouture, the sympathetic biographer of Léon Blum, Pierre Mendès France, François Mauriac, Nasser, and Ho Chi Minh, and a correspondent for Le Monde, who was far from enthusiastic when De Gaulle returned to power in 1958, has mellowed, too.2 Fortunately he does not try to round off the General’s rough edges. Jean Lacouture’s De Gaulle is not a nice man. “Armored with pride and rigidity,” this “great intellectual beast of prey,…virtuoso of domination” inflicts “sarcastic badgering” on his subordinates, treats his associates unfairly, shows “obsessive distrust,” makes unreasonable demands on his allies, and displays a “superiority complex.” Though De Gaulle clearly has the dimensions of a hero in Lacouture’s appropriately grand-scaled account, the hero seems more authentic without incense.

Lacouture is quite frank about what he regards as De Gaulle’s mistakes and failures. As the French Army’s most famous modernizer in the 1930s, De Gaulle underrated air power. After his momentous appeal from London on June 18, 1940, to all those French willing to continue to fight Hitler, he failed, for many months, to rally more than two other French senior officers to his side (General Catroux, Admiral Muselier). His first attempt to install his Free French forces in French territory, at Dakar, in the fall of 1940 was humiliatingly rebuffed by the authorities there who remained loyal to Marshal Pétain. He needlessly alienated many of his first supporters in wartime Britain by “overweening and even provocative” steps. His “irritating stridency and verbal excesses” over restoring French power in Lebanon and Syria nearly led to a complete break with the indispensable Churchill in 1942, and in the bombardment of Damascus in May 1945 “De Gaulle and his representatives in the Levant…acted clumsily, provocatively, and brutally.”

Even in the triumph of the Liberation, Lacouture blames De Gaulle for mistakes and failures. He pursued the old French nationalist dream of detaching the Rhineland from Germany with such “grandiose determination” that it “began to look ridiculous.” He reasserted French claims to Indochina by force, and opposed the concessions to Ho Chi Minh that might have averted war there in 1946. When he resigned in a huff as president of the Provisional Government in January 1946, he imagined that public opinion would call him back at once. His hands were not as clean as was once believed during the May 1958 military revolt in Algeria which frightened the Republic’s leaders into recalling him to power. Even in his negotiation of peace in Algeria in 1962, arguably his supreme achievement, he was not “at his best” and failed to get all the concessions for French strategic interests and for the European settlers that more patience might have obtained.

In the visit to Quebec during which the General, swept up by the enthusiasm of the crowd (Lacouture, who was present as a journalist, is memorably vivid here), uttered his celebrated “vivi le Québec libre!” he “in the strict sense interfered in the internal relations of a foreign state.” He erred in thinking that the Québecois wanted to be “Canadian French.” The famous phrase about the Israelis, “an élite people, self-confident and dominating,” with which De Gaulle announced his pro-Arab turn of 1967, was needlessly one-sided (though hardly negative in the Gaullist lexicon). He underestimated the weight of ideology in Eastern Europe (at least in the short term), and his dream of loosening the iron curtain was smashed by the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Advertisement

These blemishes make the hero’s successes all the more convincing. It was at the crucial moments, and with respect to the most fundamental issues, that De Gaulle seems in retrospect mostly right. With his rough and unyielding character he took positions that look steadily better with time. He was right to reject an armistice with Hitler in June 1940. He was right about getting out of Algeria (though he had hoped for some kind of longterm association of Algeria with a French Commonwealth). As for the things that made Americans angriest in the 1960s, either he looks reasonable (recognition of Communist China, peace in Indochina), or the issue has been overtaken by events (after all, the Spanish now have the same arrangement with NATO the French insisted on—inside the alliance, but outside the integrated military command). He seems even more right now about the decay of the two ideological blocs and the transiency of the cold war than when Lacouture wrote the French version of his book. Even the phrase that aroused the most derision at the time, Europe “from the Atlantic to the Urals,” looks prophetic. The popularly elected presidency he established is the first constitutional arrangement for the executive generally accepted in France since 1789. Perhaps most impressive, when he had vast powers in his hands, he rarely abused them.

While the other members of the World War II “Big Five” have been dethroned (Stalin, Chiang Kai-shek) or at least diminished from their wartime adulation (Churchill, Roosevelt), De Gaulle’s reputation has posthumously grown. De Gaulle was always an anomaly among them. That he was there at all reflected willpower and nuisance value rather than real resources. How many divisions did he have?

Several special qualities make it legitimate to call De Gaulle a great man. First, he was a genius at playing a weak hand. He was “never as great as in adversity.” He understood in June 1940, when he summoned the French in the teeth of almost their entire national leadership to continue fighting Hitler, that he could succeed only by the diplomacy of “nuisance.” The claim of this obscure temporary Brigadier General to embody French sovereignty at that moment was so purely symbolic that to give in on any point was to lose everything. That strategy worked, of course, only because Churchill valued De Gaulle’s intransigence against Hitler (and coveted his supposed access to the French empire) more than he resented De Gaulle’s affronts. Even Churchill, Lacouture shows, came close to dropping the impossible Frenchman in the spring of 1943 over rivalries in the Middle East. De Gaulle knew exactly how far he could push his nuisance diplomacy, and to the very end of his long life he played his limited resources to the brink, but never beyond.

De Gaulle’s instincts for attack were tempered by a realistic sense of limits. Behind the appearance of rigidity De Gaulle knew how to adapt. He did not chase his phantoms to the point where they became destructive to France. A lucid grasp of historical trends and a fundamental decency showed him where to stop. The list of his intelligent strategic retreats is a long one: he gave up formal colonial empire in favor of informal economic influence. He gave up the annexation of the Rhineland in favor of reconciliation with the western half of a divided Germany, national economic autonomy in favor of a leading role in the Common Market.

De Gaulle adjusted well to reality because he was able to transcend the narrow views of his own milieu—the surest mark of a great man. De Gaulle was a professional officer, a Catholic, and an aristocrat, but he was a prisoner of none of these groups’ prejudices. Lacouture has unearthed telling details about the family, minor nobility with traditions of intellectual and public service rather than of making money. De Gaulle’s father, a history professor in a Catholic school, was already a man of some freedom of spirit (he understood that Dreyfus was innocent, for example); an aunt was an even more prolific writer than the General was to be. The family’s greatest bequest to the young Charles was intellectual and moral independence.

Advertisement

Much nonsense has been written about De Gaulle’s intellectual background. When his Rally for the French People was growing swiftly in 1948, he was accused of borrowing the techniques of nationalist mass politics from fascism. At the height of the animosity provoked by his secession from the American cold war bloc, he was called pro-Communist.3 Lacouture shows that the formative influences on the young Charles were social Catholicism, and not Action française, as is sometimes claimed. Those influences persisted to the end, as demonstrated by De Gaulle’s enthusiasm for worker participation in control of industries at the end of his presidency. But De Gaulle was never locked into any doctrine except a determination to give France the greatest role possible in a hostile world.

De Gaulle’s vision of the world was a dour and pessimistic one, foreign to the easy optimism once standard among Americans. History for De Gaulle was a struggle among the world’s peoples to surmount the decline and mediocrity that stalked them all. Given the right leadership and an effective state, authentic peoples—those with a history rich in declines and renewals: the French, the Germans, the British, the Russians (he wasn’t so sure about the callow Americans)—could perform great deeds. In this harsh game of power politics, a real leader must know how to play off alliances and enmities with daring and skill. Lacouture quotes De Gaulle interrupting a cabinet meeting to reprove a minister who had just spoken of “our friends”: in world affairs, growled the General, there are no friends.

Given his purely instrumental view of alliances, De Gaulle’s relations with his allies were inevitably stormy. Lacouture takes the time to explore in detail his turbulent relations with the British, the Russians (not “the Communists,” for De Gaulle believed that peoples, not ideologies, ruled history), the Germans, and the Americans. Lacouture has gone out of his way to state the other side’s point of view in the disputes that marked De Gaulle’s relations with these peoples, and he is willing to say at times that De Gaulle treated them badly.

As for the United States, Lacouture is probably right to insist that De Gaulle was never “anti-American” in any simple sense. Indeed, in June 1940 De Gaulle staked his life and career on the faith that American industrial might would eventually allow Churchill to prevail over Hitler. It was Roosevelt who poisoned the relationship. FDR looks stubborn and vindictive in this book, and the expressions of his contempt for France that Lacouture unearthed are painful to read. Here Lacouture can not contain an anger that is rare in this usually fairminded book. He calls Roosevelt an “enemy” and a “colonial potentate.” “In its most harrowing, wounding days, did French colonialism ever behave toward its overseas territories in as blind, more contemptuous way” than Roosevelt behaved toward De Gaulle (and, by extension, France)?

Lacouture could have acknowledged even more clearly that a hostile image of De Gaulle was suggested to Roosevelt primarily by French exiles, notably Alexis Léger (the poet St. John Perse), who had been the top career official of the French foreign office up to May 1940, who loathed De Gaulle, and who was regarded as infallible on European affairs by leading figures in Washington such as Sumner Welles. Also Roosevelt’s “Vichy gamble,” in which he recognized Pétain’s government, was not the product of affection for the aged Marshal Pétain (though his World War I reputation remained high) or even less for his authoritarian government, but was a Gaullian act of Realpolitik on Roosevelt’s part. The error was to have clung so stubbornly to that initial position, refusing to acknowledge long after other statesmen that the Free French really spoke for most French people. The United States was the last country in the world to extend official recognition to De Gaulle’s provisional government, not until October 23, 1944, more than four months after the Normandy landing.

De Gaulle’s world view was incompatible with most Americans’ feelings about alliances, which they seem to have confused with a love affair. The most galling of De Gaulle’s cold calculations in the 1960s was that since the United States had to defend Western Europe anyway, France did not have to buy American military commitment by submerging her national identity within NATO. The Americans also resented De Gaulle’s further cold calculation that, after the Soviets had obtained the means of destroying America with nuclear weapons, the Americans might not trade Boston for Lyon, and that France must therefore possess its independent nuclear attack force in order to oblige the Americans to share in a nuclear response to a Russian advance.

When, on the other hand, the Russians acted aggressively, De Gaulle was always the firmest supporter of Western resistance alongside the United States: over Khrushchev’s threats to Berlin in 1961, in the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, and against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. De Gaulle must be understood as keeping several possible choices of policy open at any one time, one of which was support for the US in case of Russian aggression, while another was independence of American hegemony in calm times. The multiple policies were coordinated by a single goal: to make the French feel ready to play the role of a great people—if necessary by symbolic triumphs.

De Gaulle was a master of the symbols and psychology of power even when he did not possess the reality.4 He knew how to get maximum mileage from symbolic independence when the reality was beyond French means. Lacouture neglects to mention the polite secret that the French force de frappe depended on American-made tanker aircraft, for example. Richard H. Ullmann’s revelations that the United States quietly began assisting the French nuclear weapons program when Richard Nixon and his foreign policy adviser Henry Kissinger entered office, a few months before De Gaulle’s departure, were published too late for Lacouture to use.5

De Gaulle’s final claim to greatness was his personal austerity. He never let power demean him with its usual petty vanities. He adamantly refused any more stars than the two he had worn in London; he had better ways to make five-star generals quail when he appeared on television in his unadorned military tunic, at the worst moments of the army’s resistance to Algerian independence. He continued to occupy his plain, slightly dowdy country house at Colombey. The instructions he drew up in 1952 forbidding any state funeral remained in force even after his eleven years as president. The world leaders who came to Paris in 1970 had to be content with a memorial service, without a coffin, in Notre Dame; they were excluded from the family funeral at Colombey, though the villagers were not. He would have loathed the concrete Cross of Lorraine.

In the end, does anything remain of what De Gaulle tried to build? Lacouture admits that the long-term practical attainments are modest. And De Gaulle knew it, for his mood at the end was dark. As both a visionary and a realist, he took a tragic view of the transience of his own leadership. France remains a middling power; and, as De Gaulle predicted, for lack of “great projects,” the French have gradually lost direction and slipped into sterile political quarrels. Europe has resumed the creep toward supranationality that De Gaulle stopped in 1965, and Germany, not France, will probably dominate its future.

A reader may wish to ask even more fundamental questions than Lacouture has done about De Gaulle’s legacy. De Gaulle was a nationalist, albeit one of balanced and decent views, in a world which is in danger of perishing of nationalism. Did not De Gaulle make the world an even more dangerous place? Believing that a duel of nations was inevitable, De Gaulle helped turn it into a nuclear duel by resisting efforts to stop nuclear proliferation. Only leaders of De Gaulle’s lucidity and restraint can make such a world livable, and they are rare.

The major positive legacy of De Gaulle is his myth: the recovered self-confidence of the French and the stable institutions of the Fifth Republic which, though tailor-made for the General, have proven both resilient and popular. Surely the vigorous and independent Fifth Republic has been better for United States interests than the more pliant but basically more resentful Fourth Republic.

Jean Lacouture has written a biography of a very high order. It is not merely that, as a skillful and indefatigable journalist, he has interviewed everyone and seen everything. Nor is it merely that he knows how to build vivid images—the lonely general and his extravagant claim in 1940, the crowd scenes at the Liberation of Paris or in Quebec. Lacouture’s long sonorous phrases take on some of the majesty of the subject. He has a gift for restoring a sense of the different but now forgotten choices that faced De Gaulle. For example, the self-evident course in June 1940, in the short term, would have been simply to create a French Legion in London, leaving the issue of French sovereignty for later—or never.

What really distinguishes Lacouture’s book is something much more powerful than simply admiration: a sense of profound historical irony. The very qualities that made De Gaulle a dislikable human being also equipped him to perceive and follow his lonely course. The point comes home dramatically as De Gaulle, that “cold monster of the State,” as Lacouture calls him, snubbed the Resistance leaders who had helped open Paris to him in August 1944 but who threatened his administrative authority. But if De Gaulle had been a more accommodating person, Lacouture remarks, would he have reached Paris at all?

The one thing wrong with this book is the American editors’ decision, over the author’s protest, to squeeze the 1,588 pages of the French volumes II and III into the 640 pages of the English Volume II. Excising whole sentences or paragraphs rather than compressing them made matters worse, for essential connecting information has sometimes been deleted. Even in its regrettably truncated English edition, however, Jean Lacouture’s book will be the indispensable work on De Gaulle for a long time.

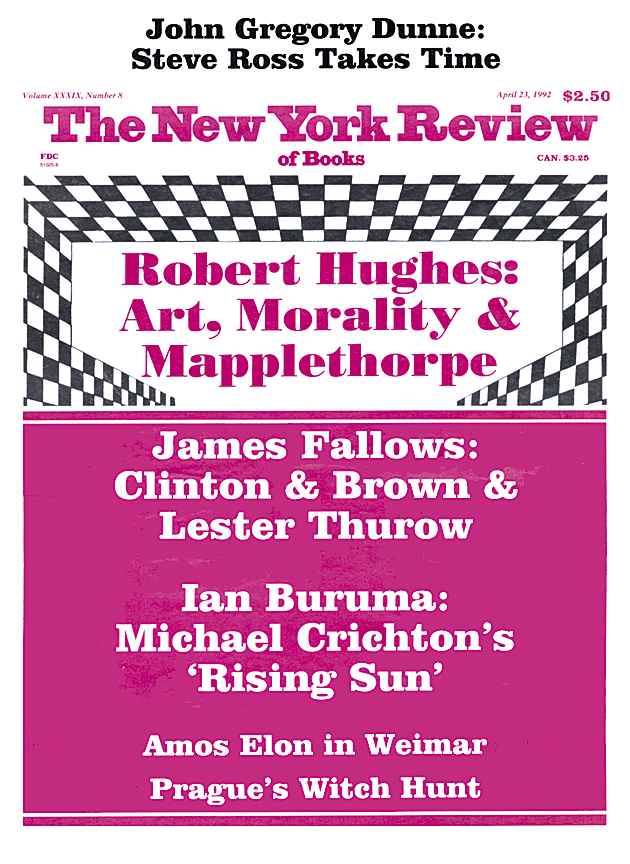

This Issue

April 23, 1992

-

1

A demain De Gaulle (Paris: Gallimard, 1990). ↩

-

2

Lacouture’s earlier De Gaulle (London: Hutchinson, 1970) was more critical than the present work. ↩

-

3

The Australian journalist Brian Crozier made this bizarre case in De Gaulle (Scribner’s, 1973). ↩

-

4

The classic analysis of De Gaulle’s leadership remains Inge and Stanley Hoffmann’s “De Gaulle as Political Artist: The Will to Grandeur,” in Stanley Hoffmann, Decline or Renewal? France Since the 1930s (Viking, 1974). ↩

-

5

Richard H. Ullmann, “The Covert French Connection,” Foreign Policy No. 75 (Summer 1989), pp. 3–33. ↩