Michael Cunningham’s novels have tended to be airy, open structures, covering large spans of time and space. They are narrative experiments, multivoiced and wide-ranging, with a romantic sense of the adventure of the inner life and a brilliant eye for the details of the everyday world; it is not surprising that Virginia Woolf has been so important a presence for this midwestern New Yorker. In A Home at the End of the World (1990) he followed three very different misfits from childhood to maturity, from Cleveland to New York City and then to the broken-down upstate farmhouse where they define themselves, perilously and poignantly, as a kind of polymorphous family. They tell the story in turns, a play of subjectivities.

The Hours (1998), like its template Mrs. Dalloway, unfolds over one day, but it refracts that day through different periods and places—Virginia Woolf’s Richmond in 1923, Laura Brown’s Los Angeles in 1949, Clarissa Vaughan’s Manhattan in “the late twentieth century.” Across seventy years and thousands of miles three women’s lives are given a mysterious harmonic resonance, reinforced by the bold pastiche of Woolf’s stream of consciousness in which the novel is written. In Specimen Days (2005), Cunningham’s wildest experiment, three disjunct periods are handled through the conventions of three distinct genres: the Victorian ghost story, the contemporary police thriller, and the futuristic sci-fi dystopia. Here the presiding literary presence is a different kind of poet of the self, Walt Whitman, his words channeled by a nineteenth-century child visionary and adopted as arcane mantras by twenty-first-century child suicide bombers.

If Specimen Days, enjoyable though it was, seemed an adventure too far, Cunningham’s new novel By Nightfall is by contrast disconcertingly conventional in subject and technique. It is seen entirely through one consciousness, takes place in and around New York City, and unfolds over a period of a few days (albeit bulked out with substantial flashbacks). Its main character, Peter Harris, is a middle-aged second-rank contemporary art dealer, his wife Rebecca is a magazine editor, and the novel’s social milieu is largely middle-class. Cunningham has reined in his keen and compassionate social sense to concentrate on a small and perhaps less original canvas. His great gifts are everywhere apparent—the wonderfully exact notation of feelings and sensations and appearances, the observant lyricism, the elegant wit—but the cumulative impact of the novel is oddly muted.

It’s true that Peter Harris himself is dissatisfied with the limitations of a world whose comforts he nonetheless values. As an art dealer he lives in a complex but confined space between commerce and creativity, fashion and idealism. He longs for the transcendence that he sees as the gift of art itself—he sees his job, for all its inevitable disappointments, as “the unending effort to find a balance between sentiment and irony, between beauty and rigor, and in so doing open a crack in the substance of the world through which mortal truth might shine.” In a highly wrought, almost hallucinatory flashback, Peter remembers an adolescent holiday at a lakeside house and a visionary experience he had there, “a sea-swell of feeling, utterly unexpected, a sensation that starts in his bowels and fluoresces through his body, dizzying, giddying.” He was watching a girl he had a crush on standing ankle-deep in lake water with his brother:

It’s not lust, not precisely lust, though it has lust in it. It’s a pure, thrilling, and slightly terrifying apprehension of what he will later call beauty, though the word is insufficient. It’s a tingling sense of divine presence, of the unspeakable perfection of everything that exists now and will exist in the future.

These are the sort of longings lying semidormant in the heart of a man busy in the stratagems and persiflage of the art market. From the start Peter admits to being at odds with himself, “as if he hasn’t quite mastered the dialect of his own language” and is “dressing as the man who’s impersonating the man he actually is.” The man he actually is is ripe for a midlife crisis.

The substance of his world cracks open not long after the arrival at the Harrises’ SoHo apartment of Rebecca’s younger brother Ethan—so much younger that he is dubbed “the Mistake” by his family, and known as Mizzy for short. Mizzy is a beautiful drifter, with a history of drug problems and the clever addict’s plausibility and deftness at lying. After a period meditating in a Japanese garden he has returned to the States with the idea that he might do “something in the arts”; and Peter agrees to let him stay with them while he turns himself around. The Harrises’ only child, Bea, has left home and is working in a bar in Boston. She is alienated from her parents for reasons they don’t fully understand, but which cause them much grief and guilt, and their taking in of Mizzy seems in a way a chance to make good on their earlier parental failure. In fact the visit, which fails to save Mizzy, upends Peter’s own life.

Advertisement

We learn that Peter’s brother was gay, and had died of AIDS, but Peter himself seems never to have been drawn to other men until, at the age of forty-four, he falls in love with the unattached and unknowable Mizzy. Cunningham has always been the most levelheaded of gay novelists. By never making an issue of gayness he simply but subtly deepens our sense of its being unarguable. He writes wisely about gay lives and desires as completely natural, and seems never to have been tempted by the more programmatic or socially exclusive kinds of gay fiction. The poet Richard in The Hours presents a memorable image of a mind and body ravaged by AIDS, but The Hours is not an “AIDS novel.” Cunningham’s rightful and capable claim has always been to represent life in general, from the viewpoint of either gender and in the light of all kinds of sexual persuasion. He has described before now a more ambiguous territory of desire, which one might call bisexual were his point not so clearly the exploration rather than the classification of feeling. In A Home at the End of the World, the sweet and inarticulate Bobby has an intense and partly sexual relationship with gay Jonathan before starting an affair with the older Clare and fathering a child by her.

Early on in By Nightfall, to set Peter up as a properly functional straight man, there’s a two-page sex scene (foreplay, cunnilingus gone into in pungent detail) that seems also to proclaim the author’s entitlement to write such an episode. There’s perhaps a bit of the “gay grapple” about it, that extra determination with which a gay actor sometimes goes at a straight love scene; but it’s effective, and remains in the mind as a kind of carnal counterpoint to the two kisses (one “semi-chaste,” the other “not exactly, not entirely, sexual”) that are all that happens physically between Peter and Mizzy.

The area of sexual ambiguity is first entered through a simple confusion, cinematically caught: coming home one afternoon Peter finds Rebecca in the shower, “the pink blur of her behind the frosted glass shower door,” which he opens to see her, from behind, rejuvenated (typically, he thinks of a Rodin bronze he’s just been looking at in the Met). Then she turns, surprised. “It isn’t Rebecca. It’s Mizzy. It’s the Mistake.” Mizzy is certainly trouble, but the suggestion that the brother-in-law embodies something already desired in the wife, a latent alternative, also sets the limits on Peter’s crisis. You feel he’s not about to turn queer, go running off to gay bars. It’s not really even a crisis of sexual identity, but something stranger and more old-fashioned, the disruption of a man’s life by a vision or visitation of beauty. At the end of the novel Peter claims, perhaps to the reader’s surprise, that he would have left Rebecca for Mizzy, given the chance; but we sense quite strongly that this is a peculiar, one-off infatuation, something with a slight air of fable to it.

Mizzy may be physically shameless, “no, more like shame-free, satyrlike, so unembarrassed by nakedness or by biological functions that he makes almost everyone else seem like a Victorian aunt”; but there is already something very nearly Victorian in Peter’s immediate reflex of idealizing Mizzy’s beauty—his highfalutin talk of his “pristine nascency” and “slumbering perfection” and supposed resemblance to “a bas-relief on the sarcophagus of a medieval soldier.” Later in the novel, Peter comes to think of Mizzy as “his favorite work of art, a performance piece if you will”; he “wants to collect him…to curate Mizzy.” By the end he understands his love for the boy as love for “Beauty itself.” Nearly a century after Death in Venice, and in a culture where mainstream novels such as this one carry detailed descriptions of sexual acts, there may seem something rather quaint about this chaste and preciously phrased longing of an older man for a surely unattainable younger one. Cunningham touches in appropriate allusions—Peter’s camp hairdresser asking him, “Peter, darling, have you thought of getting rid of some of this gray?” and Mizzy himself reading Thomas Mann—but exact analogies with Mann’s Aschenbach are wisely not pressed too hard.

Both, however, face a moral quandary to do with saving the loved one: Should Aschenbach tell Tadzio’s family to leave the cholera-threatened city, and so lose sight of him forever? Should Peter try to save Mizzy from his drug habit? Back home unexpectedly one day, he overhears Mizzy, who has claimed to be clean, making a phone call and, unaware that Peter is in the apartment, taking delivery of something. He knows he should report this fact to Rebecca, committed to saving her brother from the early death that further addiction may well represent; but he doesn’t want Mizzy sent away to rehab, Mizzy himself doesn’t want to go, and he enters into a tense concealment of the truth that is charged with his inadmissible feelings for the young man. The emotional waters are muddied, and when Mizzy seems to make himself available to Peter, Peter can’t be sure if he’s doing so out of desire or (old-fashionedly again) in the hope of blackmailing him.

Advertisement

Cunningham has often and rightly been praised for his generosity, his forgiving but unsentimental presentation of his characters’ inner lives—a quality that fosters a particular intimacy between reader, character, and writer. It’s a generosity that manifests itself in both feeling and style, a gift of insight and eloquence from author to character that is not without its occasional hazards. Inarticulate Bobby, in A Home at the End of the World, whose conversation rarely rises above “Uh-huh,” “You know,” and “I don’t know,” becomes a lexical master, a prose-poet, in the sections of the book “written” by him. He will note, for instance, the “porcine squeak of the hinges” when a door is opened; or listening to Steve Reich he will be reminded of “my adult days in Cleveland, those little variations laid over an ancient luxury of replication.” These are fine observations, but they are Cunningham’s, not Bobby’s, and the unresolved difference between Bobby as seen from the outside and the inside sometimes threatens to become a problem. In the desire to endow his character with insight, Cunningham risks violating the character himself, or even seeming to patronize him by such ample redemptive touches. It is a measure of his skill and humanity that by and large we overlook the incongruities because he has made us care about Bobby so much.

Cunningham’s alertness to the selfhood of other people is everywhere apparent in By Nightfall. Rebecca “brings the vitality of herself—her offhand sense of her own consequence”; Mizzy “feels like a fantasy he’s having, his own dream of self, made manifest to others”; Peter exhibits an artist whose video installations show ordinary citizens in repeated commonplace actions, but these figures “do, of course, each of them, carry within them a jewel of self, not just the wounds and the hopes but an innerness.” Even things partake of this quality: Central Park at night is “sunk in its green-black dream of itself,” the Metropolitan Museum has the “capacity to excite the very molecules of its own air with a sense of reverent occasion and queenly glamour”; by the end the whole world “is doing what it always does, demonstrating itself to itself.” In the highly effective plot twist of the final pages Peter is made to reinterpret his own actions and fantasies as sins not of passion but of neglect: he tells himself, “You have failed in the most base and human of ways—you have not imagined the lives of others.” It’s a striking moment in part because the character convicts himself on a charge that could never be leveled against his creator.

Perhaps the faint but pervasive suspicion in By Nightfall that a slender donnée has been bulked up to make a novel has something to do with this very proficiency of Cunningham’s, his luxuriant ability to imagine his characters’ lives in the round. He’s the sort of sculptor who seems to promise that even those parts of the figure you can’t see are carved in loving and lifelike detail. The Taylors, Rebecca’s family, as well as Peter’s own, are delved into in Peter’s mind with an abundance of remembered fact and color—old Cyrus Taylor taking refuge in his study, his wife’s eccentricities hardening with age, the different schools two of the daughters were at, Rebecca at Columbia and Julie in medical school, while the other was “engaged in an epic battle with her first husband out in San Diego.” We see Peter visiting their house some years before and finding a dead mouse behind the ficus in a corner of the living room and scooping it up in a dustpan. It’s not that any of these details rings untrue, but that after a while the richness of recall seems to become an end in itself, the novel an invitation to admire Cunningham’s depth of acquaintance with his own creations, even those, like most of the above, who don’t figure in the present-day story at all.

When Peter is driven in a rich client’s navy-blue BMW he gives himself up to half a page of speculation about the unknown private life of the chauffeur. It’s not entirely irrelevant, because Peter knows that an art dealer too is merely a servant to a client, whatever show of friendliness and equality may be made; there’s a hint of fraternity with this other employee, though neither man knows the mystery of the other’s selfhood. Nonetheless, the passage heightens the slight air of factitiousness in the novel, of an author very capably treading water.

This is doubtless an ungrateful, and ungenerous, criticism. If the novelist should be, in Henry James’s phrase, “one on whom nothing is lost,” and if he’s writing from the point of view of one character, then that character will need to be a keen absorber and shaper of impressions himself. And Peter certainly, and in general convincingly, is such a man. He seems to notice almost in spite of himself. After a painful final meeting with Mizzy at a local Starbucks, Peter heads back to the gallery: “He’s not so far gone as to ignore the rampancy of the streets through which he walks.” In fact, far from ignoring it in his distress and humiliation, he registers every detail—the “hunkered-down hurriers,” the bin-scavengers, the precise meaningless chatter of five teenage girls—with a sorry sense that “it’s the world, you live in it, even if some boy has made a fool of you.” And who but Peter Harris, having noted it, would actually call it “rampancy”?

In The Hours Cunningham presented his inner monologues in the sallies and lulls of Woolfian reflection, with its easy reach from the trivial to the sublime, its oscillations of mood. In By Nightfall the register is necessarily more masculine, the oscillations now between a language of transcendence and a kind of cornered, caustic blokishness. At times it flows and glows, at others runs curtly down the page in staccato one-sentence paragraphs like stage directions. The book is much taken up with the banalities of business and the scrupulous remarking of the unremarkable (decisions about whether to have breakfast or grab a Starbucks sandwich en route, exact details of a Chinese take-out order, Peter’s briefs with a “small pee-stain, barely noticeable” but nonetheless somehow thought worth noticing). Admirers of Cunningham may be slightly disappointed by the untransfigured ordinariness of some of this material, which only just scrapes in under cover of Woolf’s injunction in “Modern Fiction” to “examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.” (And we have seen that Peter, with his tendency to “soul-surges,” is in many ways far from ordinary.) The anxieties of gallery life—can Peter take a probably promising artist from another dealer? Would it be wise to let a probably less promising one go?—are expertly, even knowingly, handled, but perhaps don’t generate quite enough imaginative heat.

What Cunningham is trying for here is an inner voice that does justice to the high and the low, the venal and the visionary, within one man’s consciousness. Stepping from an elevator “into a crepuscular columned vastness, like the grand foyer of some grimy dilapidated palace,” Peter thinks, “Motherfucker has the whole goddamned floor.” Reflecting on the “exhausting preciousness” of a client’s house, he sees it as “beautiful in a way that will probably charm you if you’re ignorant about furniture and art but will dazzle and humble you if you know your shit.” Peter himself knows his shit inside-out, and has an art-historical example to hand even at stressful moments that require quick thinking: “Youth. Heartless, cynical, despairing youth. It always wins, doesn’t it? We revere Manet, but we don’t see him naked in a painting. He’s the bearded guy behind the easel, paying homage.” This duality, at the heart of the novel, finds expression at its end in the repeated citing of Flaubert’s famous paradox, that we are all “banging on a tub to make a bear dance when we would move the stars to pity,” an image that seems to represent to Peter the scope of his own ambitions and failures.

His crisis is dressed from start to finish in references to the great writers and artists he seeks to live his “big ambiguous motherfucking heartbreaking life” by. It’s a practice Cunningham himself has pursued in his novels written in the light and shadow of earlier writers, such as Woolf and Whitman, who lend their splendor to these latter-day books while showing them up (how can they help it?) as poor relations. Peter’s final conversation with Rebecca takes place against a nocturnal snowfall, seen beyond the bedroom window, and evoked in words, phrases, rhythms that echo the snowfall in the magnificent final paragraph of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” Readers will decide for themselves if this is a subtle intertextual success (the opening of Ulysses is alluded to on the first page of the novel) or a small but telling lapse of judgment, caused by the very desire to give weight and transcendence to the tale.

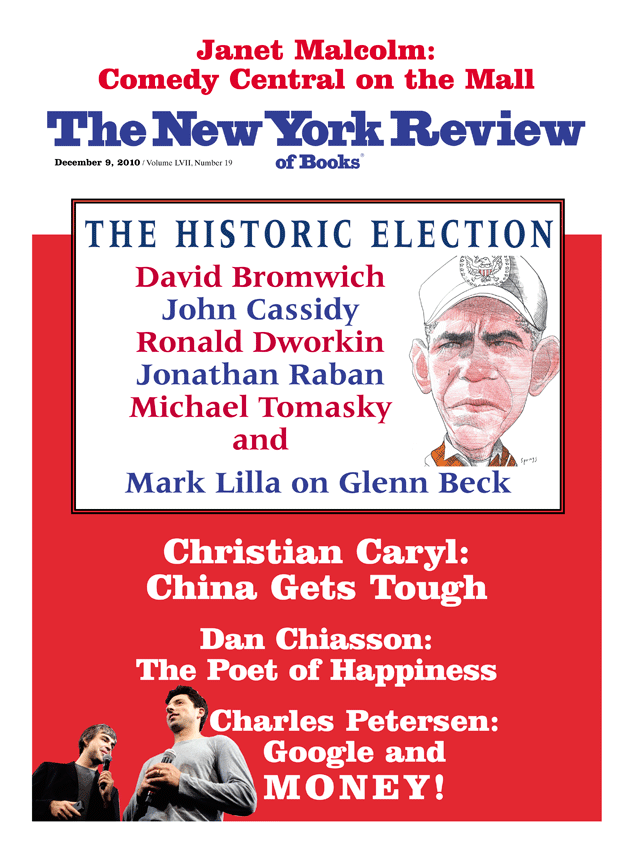

This Issue

December 9, 2010