Gossip

The hostile review of Isaiah Berlin’s correspondence by A.N. Wilson in the TLS*—which has set off a heated controversy about Berlin and his reputation—exhibited a misunderstanding of university life as well as of the nature of Sir Isaiah’s career. Wilson was unappreciative of Berlin as a historian, comparing him unfavorably with his close contemporary the Oxford historian A.L. Rowse. Neither were truly major historians but Berlin was not really a historian at all, in the full sense of that word, nor was he exactly a philosopher. His field, largely untrodden and little understood, was the intersection of philosophy, aesthetics, and history: in this, his achievement was very great, above all in his profound elucidation of the way that ideas like freedom, enlightenment, and nationalism could appear, develop, and be challenged in politics and art from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries.

He never aspired to be a historian of ideas in the grand general sense—that is, to give a complete intellectual image of any era—but only to reveal the contradictions and paradoxes in the historical development of ideas that we still grapple with today. Even though it is true that his conversation, at least in my own acquaintance with him, was even more brilliant than his writing, his essays on Johann Georg Hamann, Johann Gottfried Herder, Joseph de Maistre, Alexander Herzen, and others will retain their interest and value for a long time to come.

Wilson’s main complaint about Berlin’s letters is the frequently malicious comments about life in Oxford. Not that malice is absent from Wilson’s review. In his case, however, it is often inexplicable. The review is entitled “The Dictaphone Don,” and this is surely intended to have a pejorative edge to it. But it is not clear to me why Berlin’s habit of speaking his letters into a dictaphone is more shameful than writing on a computer or with a goose quill. On Berlin’s account of his meeting with Greta Garbo, Wilson complains that “he has not spotted her lesbianism.” Should he have? Did she give herself away, dressing in men’s clothes like Queen Christina?

The petty aspects of Wilson’s review are overshadowed when Wilson is shocked that the letters “are peppered with malice about poor A.L. Rowse” while Berlin was personally cordial to him. The open cordiality to Rowse that Wilson characterizes as “treachery” is simply a frank letter of refusal to support Rowse’s failed campaign to be elected warden of All Souls College, a refusal couched in the kindest possible language. Wilson’s claim that Rowse was “ultimately more intellectually distinguished” than Berlin is simply ludicrous. The right description for Rowse’s historical work is well put a few sentences later by Wilson—“readable, well-researched volumes”—while most authorities consider that Rowse’s writing on Shakespeare, of which he was so vain, is simply risible.

When I was Eastman Professor at Oxford for one year a long time ago (an American is chosen annually), humorous stories about Rowse circulated frequently, as his pride in his humble Cornish origins and in his subsequent intellectual renown was legendary. Both Berlin and Rowse were fellows at All Souls, a college where there are zero students (like the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study), and where the fellows are lodged and have breakfast and dinner together. In such a situation, a certain amount of malice behind the backs of colleagues who are competent and useful but personally difficult to support is a necessary and legitimate safety valve: it is certainly a fact of life in every university where I have worked, however briefly.

One story often told about Rowse is that he came down one day to breakfast at All Souls, fulminating about a bad review in The Times of his latest book, and said, “You see the way the upper class resent that I have been able to rise into their midst entirely by my own merit.” John Sparrow, then the warden of All Souls (he had been elected in 1952 over Rowse), looked up from his breakfast and said, “Rowse, whatever gives you the impression that only the rich detest you?” I would think that malice behind someone’s back is preferable to such a frontal attack, but the story reminds me of Randall Jarrell’s remark that British manners are sometimes so frightening to Americans that they would prefer no manners at all. What appalled Berlin was not only Rowse’s egoism, but his writing letters to The Times “to say that education is bad for the poor, since most of them are incurably barbarous & do badly on a little knowledge.”

In any case, malicious gossip, whether treachery or simply letting off steam, is not merely a luxury of academic life but a useful way of keeping the peace. Isaiah Berlin’s employment of it was always private and tactful, and mild compared to that of other Oxford dons like Hugh Trevor-Roper, and certainly less vicious than that exhibited a short time ago in the campaign for the election of the Professor of Poetry.

Advertisement

Among the most aggressive and significant pages of this volume of letters is the controversy between Berlin and T.S. Eliot on Eliot’s anti-Semitism—particularly his statement that “reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable”—which Eliot insisted was not racial or even religious but cultural. Their correspondence is distinguished by courteous expressions of mutual esteem from both parties. I should think that “free-thinking Jews” should feel flattered and even pleased that Eliot considered too many of us to be a danger to his dream of a right-wing Anglo-Catholic society.

A few years later, the courtesy attained comic intensity in a contest of gracious manners when Eliot sent Berlin a book, and Berlin thanked him by writing:

I feel quite sure that, for all your disclaimers, your erudition, as well as your wisdom, are far profounder than mine will ever be. Not that it would take much to be that; but it is all I can offer, sincerely, in return, and I do offer it to you in all humility and admiration.

Not to be outdone, Eliot replied:

I was already convinced that you are my superior in learning, profundity and eloquence. I am now of the opinion that you far surpass me in the art of flattery.

Berlin commented in a letter to a friend:

I have received a funny letter from T.S. Eliot, in which there is an ironical reference to me which he maintains…is a compliment. I do not know how to reply and therefore he wins.

Berlin’s courtesy and his malice were always civilized.

(A version of this article was published on the NYR blog, blogs.nybooks.com.)

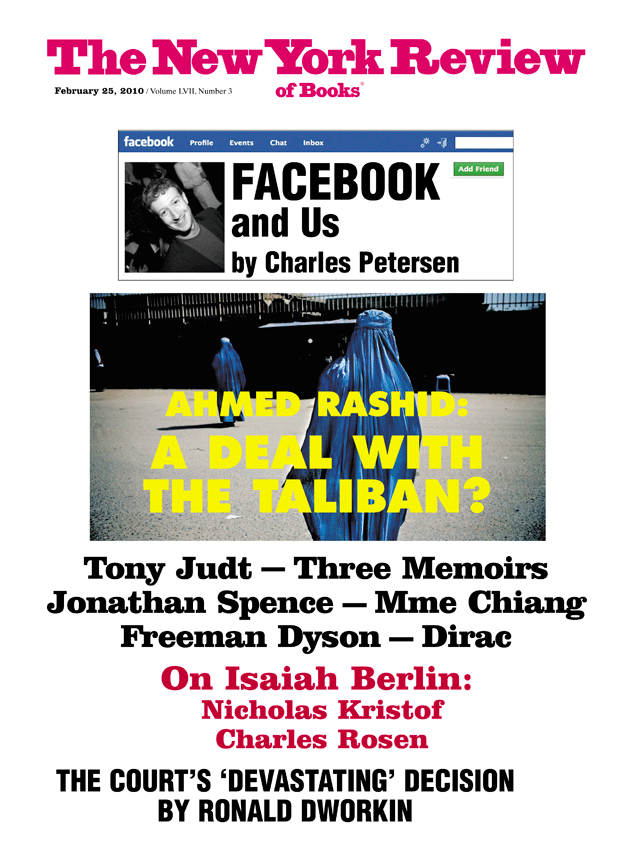

This Issue

February 25, 2010

Food

A Deal with the Taliban?

The Triumph of Madame Chiang

-

*

TLS, July 15, 2009. ↩