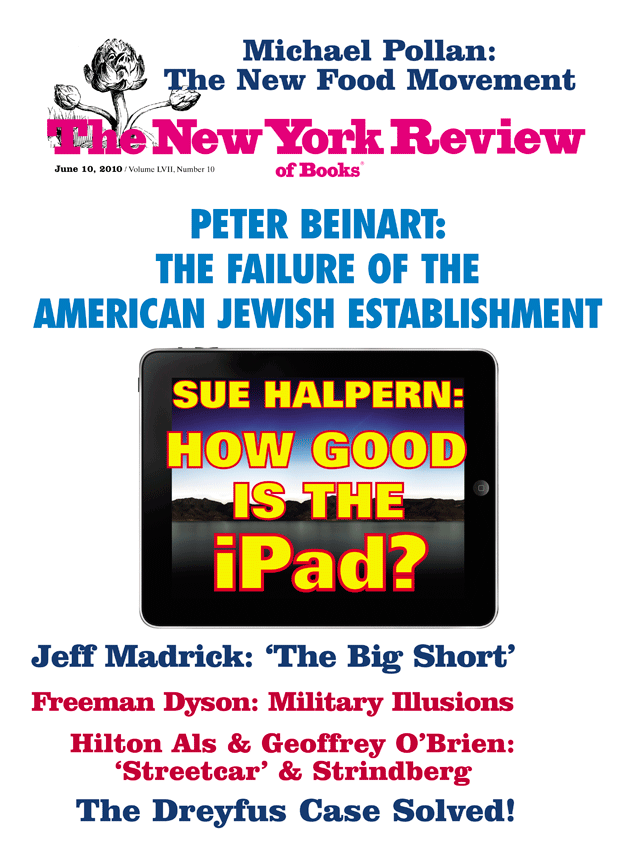

As just about every sentient being knows, Apple Computer launched its “revolutionary,”1 “game changing,”2 “magical”3 tablet computer, the iPad, on April 3. This was after years of rumors, dating back almost a decade,4 but starting in earnest in February 2006,5 when Apple filed a number of patent applications that hinted at its intentions to move into touch computing. Though this turned out to be the prelude to the iPhone, tablet rumors began building again throughout the summer and fall of 2008 and into 2009,6 despite consistent denials from the company. By following the age-old dating protocol—flirt, be coy, don’t call back, flirt some more—Apple successfully turned up the dial on desire: here was a device that, sight unseen, large numbers of people wanted and believed they had to have, even without knowing precisely what it was or what it did.

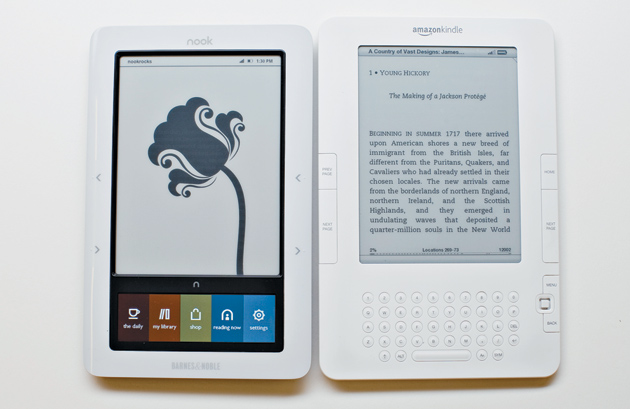

In October 2009, at about the same time that rumors about the phantom Apple tablet were beginning to swirl, but before they coalesced into a media suck, the bookstore chain Barnes and Noble issued a product announcement of its own. It was getting into the electronic book reader business (again, ten years after its failed RockBook launch) with a small device called the Nook, reminiscent of Amazon’s popular electronic book reader, the Kindle, whose dominance it meant to challenge. Though The Wall Street Journal gamely live-blogged the launch, which took place in a basement conference room at the Chelsea Piers sports complex in Manhattan, and despite an overrun of holiday preorders for the Nook, once Apple revealed, right around Christmas, that it was planning a major product announcement at the beginning of the new year, excitement that another player had entered the e-book arena dulled.

At the Nook event, there was a lot of talk about the book industry and the future of books and the promise of e-books. Stephen Riggio, the CEO of Barnes and Noble, pointed out that publishing was still big business; at $30 billion a year, it was bigger than both the music and film industries.7 He also observed that readers wanted books on demand, which is what the Nook—with its access to the Barnes and Noble catalog, as well as to the more than one million scanned public domain books already on offer through various online sites, and, most likely, to the millions of books promised by the pending Google Books settlement as well—would give them.

Riggio pointed out all the ways that the Nook was different from the Kindle: it was based on Google’s open-source Android operating system, it used the nonproprietary ePub format, it had both wireless and 3G Internet access, it had a dash of color and a rudimentary touch screen, and it could be used to play music. He didn’t have to say that with an estimated three million Kindles in circulation, Barnes and Noble was playing catch-up to Amazon. It didn’t help that, aside from having a small touch screen rather than a keyboard, the Nook looked nearly identical to its rival, or that in its first iteration, the one that landed in the hands of reviewers like The New York Times’s David Pogue, its underlying software was buggy and slow, or that due to supply issues, the company was unable to put Nooks under the Christmas tree. The machine didn’t actually ship till February, which is to say after Steve Jobs’s exultant iPad unveiling at the Yerba Buena Center in San Francisco on January 27, but before anyone could get their hands on an iPad, when desire for it was most pronounced. So while the iPad didn’t render the Nook dead on arrival, initial Nook sales, estimated to be around 60,000 units, were not strong enough to test the Kindle’s preeminence, let alone toss a lifeline to the publishing industry, if that’s what trying to capture a share of the growing electronic book market was expected to do.

Stephen Riggio was working with old data when he spoke that day at Chelsea Piers. According to the Association of American Publishers, book sales fell nearly 2 percent last year, to $23.9 billion.8 Educational books and paperbacks took the biggest hit. Their downward trajectory seemed to confirm what Steve Jobs said to The New York Times back in early 2008, when he reflected on, and then dismissed, the newly released Kindle, a device “which he said would go nowhere largely because Americans have stopped reading.” “It doesn’t matter how good or bad the product is, the fact is that people don’t read anymore,” Jobs told the Times. “Forty percent of the people in the US read one book or less last year. The whole conception is flawed at the top because people don’t read anymore.”9

Advertisement

Imagine his surprise, just two years later, when the number of book apps—books that can be read on the iPhone and iPod touch—surpassed the number of game apps in Apple’s own App Store, and sales of digital books for machines like the Kindle and the Sony Reader tripled, to over $313 million, with analysts at Goldman Sachs predicting that US sales of e-books would grow to $3.2 billion by 2015, and that Apple would command a third of that pie.10 (Google, with its plan to sell electronic versions of books through the Google Books settlement and through its own digital bookstore, Google Editions, is expected to become a dominant player as well.) Most people may not have been reading, but those who were doing so on digital readers seemed to be reading a lot.

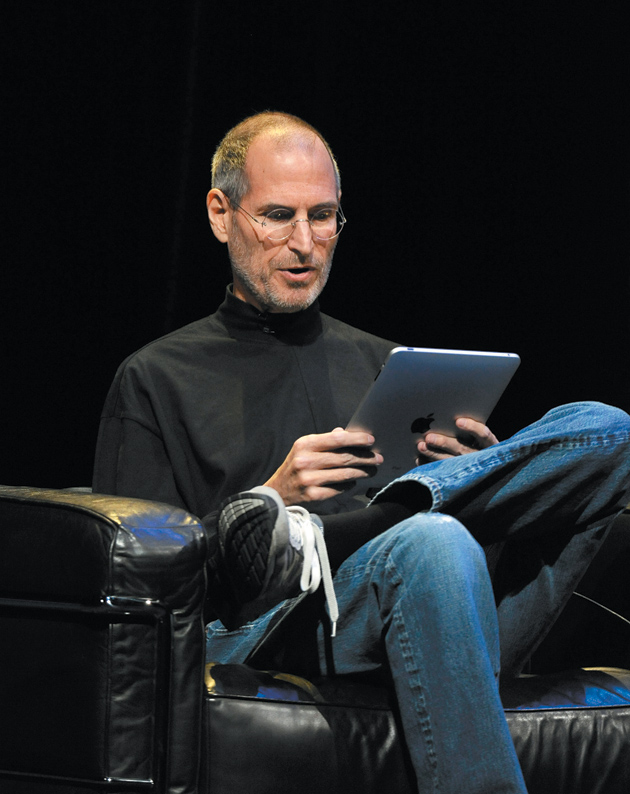

In 2008, visitors to Apple’s iTunes store downloaded one book app for every six game apps. Last year, that ratio was one to four. By the time Steve Jobs took to the Yerba Buena Center stage it was obvious that he had been wrong about readers and reading, and wrong about the Kindle itself. His mea culpa came in the form of a picture of a Kindle, projected on the big screen behind him, and the words: “That’s an e-book reader. Now, Amazon’s done a great job of pioneering this functionality with its Kindle. And we’re going to stand on their shoulders and go a bit further.” With that, he introduced Apple’s own e-book reader in the form of an iPad application called iBook. As he paced the stage, highlighting its “functionality,” the audience periodically broke out in spontaneous applause, even when it became clear that iBooks would be readable only on the iPad, and even when he noted that Apple was working directly with publishers, who would be setting their own prices, which were most likely going to be three or four or five dollars higher than Amazon’s loss-leading, penny-less-than-ten-dollars standard, and their own policies, which might keep new books off the e-book shelf so they wouldn’t compete with hardback sales. Prices and policies, that is, that appeared to favor publishers over consumers in the short run, which many publishers considered to be essential to the health of their industry.

You don’t have to be a technophobe or a Luddite to dismiss out of hand the idea of reading on a machine. Maybe it is muscle memory, but there is something deeply satisfying about a “real” book, a book made of pages bound between hard or soft covers, into which you can slip a bookmark, whose pages you can fan, whose binding you can crack and fold as you move from beginning to end. E-books, by contrast, whatever platform delivers them, are ephemeral. Yes, you can carry thousands of them in your pocket, but what will you have to show for it? What will fill your bookshelves? Then, one day, you find yourself housebound, and Wolf Hall has just won the Booker Prize, and you download a sample onto your iPhone, and just like with a book printed on paper you are pulled into the story and are grateful to be able to keep reading, and your resistance disappears, and you press the “buy” button—it’s so easy!—and that is how it starts.

There are two basic ways, so far, that words are displayed on a small screen, and those different ways offer different reading experiences that may influence whether you find reading on a handheld electronic device satisfying or not. There is “E Ink,” which reflects light rather than emitting it, and looks surprisingly like regular ink, though the page itself is grayer and offers less contrast; and there are liquid crystal displays (LCDs), pixels filled with liquid crystals arrayed in front of a light source that can be dimmed or brightened. The Kindle and the Nook, which are both monochrome readers (though the Nook has that petite color touch screen where it’s possible to see a thumbnail image of a book jacket), use E Ink. The iPhone and iPad are LCDs, and both are backlit. Backlit screens are hard, if not impossible, to read outside or in direct sunlight, and held at certain angles have a mirror effect so that the reader’s face is superimposed on the screen. Reflective E Ink screens, meanwhile, are difficult, if not impossible, to see in low light—forget reading under the covers. One is not better than the other; they are both flawed. New “transreflective” technology11 will bridge this divide, but that’s in the future.

When the Nook was announced, tech pundits wondered aloud if it would be a “Kindle killer.” It wasn’t, because, while it generally improves on Amazon’s model by, for example, being easier to navigate, it’s basically the same thing—a small, lightweight, pocketable, durable, black-and-white book reader. Both are simple to operate. Both allow access to hundreds of thousands of titles, the Kindle through Amazon’s extensive bookstore, the Nook through Barnes and Noble’s. While I prefer the Nook because it connects to the Internet through both Wi-Fi and 3G, unlike the Kindle, which has only 3G connectivity and is not operable without being tethered to a computer to retrieve books in certain geographic regions (like mine) with poor access to 3G, the reading experience is indistinguishable.

Advertisement

True, the Nook has the capacity for listening to music and now, with its most recent software update, for simple Web browsing and playing a couple of games, but these features are, so far, primitive and uninspiring. The real difference between the two machines, and the one that matters, is that the Nook is built around the ePub format, which is open and freely available for any device, unlike the Kindle’s proprietary format, which functions only for Kindle. The ePub format is used by every electronic reader except the Kindle, and promises to be a big selling point for Google Editions, the search firm’s planned Web-based electronic bookstore scheduled to launch this summer, which will allow buyers to read books and much else on any number of devices. (This may include, by year’s end, Google’s own tablet computer.) It’s through ePub that readers have instant access to millions of books in the public domain,12 that electronic publishing has a chance to become standardized, and that writers will have more options when it comes to disseminating and selling their books. As the Jacket Copy blog in the Los Angeles Times pointed out, “Theoretically, an individual author could create an EPub e-book and publish from home.”13 The implications go deep.

The headline of that piece, published the day of the iPad unveiling, was “The iPad Shows Up the Kindle.” And it did. When Steve Jobs projected the image of the iPad after his damned-with-faint-praise nod to the Kindle, the Kindle looked comically out of date, a relic, like a black-and-white TV next to a fifty-eight-inch plasma HDTV. As an analyst for the investment bank Needham and Company put it a week after the iPad went on sale and nearly half a million units flew out the door, the Kindle is “not a compelling product.”14 Even so, he and a number of other forecasters estimated that upward of three million of them would be sold in the coming year. (According to Apple, a million iPads were sold in the first month.)

What this suggests is that there remain good reasons to buy an uncompelling e-book reader like the Kindle rather than a polished, entertaining, ingenious Apple tablet. E-book readers are smaller (so far) and lighter and can slip into an even more compact space than a traditional paperback book. By contrast, the iPad is a fairly large slab, nearly as big as a page of manuscript paper and, at about 1.5 pounds, decidedly heavier. Dedicated e-book readers are considerably less expensive than the iPad and likely to drop in price to stay competitive. (Amazon has even begun giving away free Kindles to its most active book buyers, which of course will lock those buyers into continuing to purchase e-books from Amazon.) E-book readers can be used outdoors and in direct sunlight indoors. And, perhaps most crucially, even though the move is on to add Web browsing, so far electronic book readers reduce the temptation to check e-mail or the baseball score or stock prices or headlines or Twitter or all of the above every few minutes, allowing a reader to do what readers typically like to do most: get lost in the pages of a book. That the pages are not made of paper, that the ink is made from electrical charges, does not matter.

The iPad, in contrast, celebrates and enables mental roving. You can check e-mail, listen to the radio, watch a film, play poker, read the headlines, edit photos, compose a song, shop for shoes, track calories, look up recipes, and on and on, and you can read a book and write one, too (though typing on the keyboard screen is hit-or-miss and editing with Apple’s $9.99 touch-based word-processing program is as messy as eating with your fingers). What you can’t do, with few exceptions, is do these things simultaneously. You may want to check e-mail while a commercial is playing during an episode of Lost, but pressing the mail icon shuts off the ABC icon. You may need to convert dollars to kroner while searching for hotels in Oslo, but if you’re looking for those hotels on the Kayak app, it will disappear once you tap your finger on the conversion app. Multitasking, which may soon come to the iPhone, is absent here, which makes the iPad less like a computer and more like the large-print version of the iPod Touch.

Okay, that’s not completely fair: there are a number of unique applications that have been developed specifically to take advantage of the iPad’s size, resolution, and graphics, and they are either unlike anything we’ve seen before or different enough to seem original and new, and the number increases daily. There’s a realistic labyrinth that works by tilting the machine and, as the marble caroms off the sides, makes a satisfying clunk. There are also an acted-out edition of Shakespeare’s sonnets in what is called a Vook—a book with embedded video; a Netflix app that allows subscribers to stream movies; and a gorgeous, three- dimensional rendition of the periodic table. Magazines haven’t yet hit their mark (a single issue of Popular Science on the iPad costs $5 while an annual print subscription costs $12), though this could change in the coming months as more magazine publishers, like Condé Nast, cut deals for iPad-enabled editions. The free New York Times Editor’s Choice app is anemic, especially in contrast to the Web edition of the paper, but may be a placeholder or a teaser for a more robust subscription-based app in the future.

In the meantime, news organizations like the BBC, NPR, and Reuters show what’s possible with the iPad technology, providing up-to-the-minute written reports on the events of the day supplemented by high-quality, often stunning, audio and video. On the BBC site, for example, it’s possible to tune in to live radio while scrolling through the day’s stories, while NPR’s masterful application lets you read, view photos, and listen to pieces from a slew of public radio shows. Whether all this adds up to a game-changer able to revive magazine and print journalism will depend, not surprisingly, and as usual, on whether it’s innovative enough to lure consumers and advertisers into paying real money for content. At the moment, most of the news sites are both free and largely ad-free: while neither “revolutionary” nor “game-changing,” this is indeed “magical.”

One place the iPad shines is with its iBook application. Apple not only straddled Amazon’s shoulders when designing the app, it found the finest e-book application for the iPhone, called Classics, lifted its best features—a virtual bookshelf filled with the book jackets of virtual books and pages that curl and turn like paper pages—and enhanced them. Turn the iPad horizontally and the book on the screen instantly shows left and right pages. Turn it vertically and there’s a single long page. Flick the screen with your fingers and the pages fan. Flick them one at a time and you hear them turn. It’s a little cheesy—but it’s familiar, too, which makes holding and manipulating a book made of glass and metal a little less strange. Though the actual iBookstore is so far limited to less than 60,000 volumes, half of which are the public domain holdings of Project Gutenberg and the rest the thrillers, mysteries, and celebrity memoirs that top recent best-seller lists, that number will only grow as more publishers sign on with Apple, which has been much more accommodating of publishers’ interests than Amazon by letting them set prices and release dates, as well as by adopting the ePub format. (It’s still unclear how books purchased through the Google Books settlement or through Google Editions will work with iBooks.) With ePub, too, it’s also easy to retrieve free books from manybooks.net or Project Gutenberg or Google Books, as well as to download PDF files, send them to iBook, and have them appear on the iBook bookshelf ready to read. In addition, there is a stand-alone free books app.

Free books, typically, are either self-published or published before 1923 and in the public domain. Some, like Alice in Wonderland and Pride and Prejudice and the Kama Sutra, are quite popular, but for the most part, when readers seek out digital books, they are looking for titles that are contemporary, if not new. What the Kindle and the Kindle app for the iPhone/Touch demonstrated was that if the price was right, books could be an impulse buy. But immediacy—being able to push a button and having a book appear instantly on your screen—only worked if the price was low enough not to get in the way of hitting the “buy” button.

Somehow, maybe by focus group, maybe by luck, Amazon determined that the ideal price point was $9.99 and made that the sticker price for most of its titles, despite hardback prices that were often more than twice that, despite losing money on them, and despite many publishers’ belief that cheap e-books were going to cut into their bread-and-butter retail sales. For better or worse, there was a catnip quality to the $9.99 book, much the way there was for the 99-cent song. By May 2009, Kindle downloads accounted for 35 percent of Amazon’s book sales when there was a Kindle edition available,15 as the folks over at Apple were well aware, since a lot of those sales were coming through the Kindle app, not the Kindle itself.

Within days of getting into the e-bookstore business, Apple, as if to answer the question of whether higher e-book prices would put a brake on buying, anounced that 250,000 books already had been downloaded on 300,000 machines. It turns out, though, that it was fudging. By using the word “download” to describe readers’ behavior rather than “purchase,” it was not possible to distinguish between books that were added to all those new iPads without charge—free books and book samples—versus those that cost money. Whether higher prices will slow e-book sales remains to be answered. In the meantime, readers who balk at paying a premium to read books through iBooks can still buy books on the iPad using the Kindle app or one for Kobo Books, a Canadian bookseller, and in a few months through Google Editions. While their formats are not as elegant as iBooks’, it is not unusual to find a book selling for a couple of dollars less on these sites, and as soon as someone comes up with the book price comparison app, that kind of shopping will be even easier.

Of course, there’s no telling if Apple will allow such an app in its App Store, since it keeps a tight rein on what can be sold there. All software for the iPad (and iPhone and iPod Touch) goes through a lengthy vetting process and has to be approved by the company. Apple can reject software it considers too competitive with its own products, or deems inappropriate, or just does not like—it’s an arbitrary process, as shown by Apple’s rejection of an app created by political cartoonist Mark Fiore because it “ridicules public figures.”16 (The company relented after Fiore won the Pulitzer Prize.) This is its prerogative, and it’s not that different from publishing (editors routinely reject manuscripts) or retail (that’s why there are professional buyers).

Still, Apple’s vetting is the antithesis of the openness that has sparked much of the creativity and ingenuity that defines and drives the Internet. Since the release of the first browser seventeen years ago, the Internet has been an unrestricted playground, accessible to just about anyone. Its openness is why some governments fear it, why certain corporations are threatened by it, why a formerly unknown singer can sell a million albums, why a teenager in Mumbai can contribute computer code to a piece of software developed in Amsterdam and distributed globally.

The Open Source movement and Creative Commons both derive from the Internet’s essential freedom, a leveling that allows designers and filmmakers and singers and craftsmen and any number of writers, activists, politicians, artists, and entrepreneurs, many of them amateurs, to develop and disseminate their ideas. Imagine what the Internet, and our lives, would be like if, after inventing the Mosaic Web browser back in 1993, Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina not only required users to buy it but required payment for every click or download or page view. Try to imagine how a privatized, monetized Internet might have developed, and you can’t, because its evolutionary path would have been so different. Apple’s iPad apps may be ingenious. They may be fun and entertaining. They may be useful. What they can’t be is free of Apple’s control.

It is true that the iPad, like the iPhone and iPod Touch, comes with a Web browser app that takes the user directly to the Internet. Arguably, this makes these devices comparable to any computer and renders the complaint about gatekeeping moot. In fact, Web browsing on the iPad is less than ideal. Keeping more than one window open at a time is not possible, and Apple’s refusal to enable Flash, a piece of proprietary software owned by Adobe Systems that underlies many websites and allows for animations and video, means that those websites are either not fully functional or not available at all. But why bother going through a browser to get to YouTube or to read the AP headlines or check the weather when there is a dedicated app for each of these? This is what is really revolutionary and game-changing about the iPad: once there is an app for everything, it’s Apple’s Web, not the wide world’s.

This Issue

June 10, 2010

-

1

[http://www.macworld.com/article/146040/2010/02/ipad.html](http://www.macworld.com/article/146040/2010/02/ipad.html) ↩

-

2

[http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2362277,00.asp](http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2362277,00.asp) ↩

-

3

[http://www.cnn.com/2010/TECH/01/27/apple.tablet/index.html](http://www.cnn.com/2010/TECH/01/27/apple.tablet/index.html) ↩

-

4

[http://www.theregister.co.uk/2009/01/01/jumbo_ipod/print.html](http://www.theregister.co.uk/2009/01/01/jumbo_ipod/print.html) ↩

-

5

[http://hrmpf.com/wordpress/48/new-apple-patents/](http://hrmpf.com/wordpress/48/new-apple-patents/) ↩

-

6

[http://www.boston.com/business/technology/articles/2009/12/31/new_year_expected_to_bring_googlephone_apple_tablet/](http://www.boston.com/business/technology/articles/2009/12/31/new_year_expected_to_bring_googlephone_apple_tablet/) ↩

-

7

[http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2009/10/20/live-blogging-the-barnes-noble-nook-e-reader-launch/tab/article/](http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2009/10/20/live-blogging-the-barnes-noble-nook-e-reader-launch/tab/article/) ↩

-

8

[http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-04-07/u-s-book-sales-fell-1-8-last-year-trade-group-says-update1-.html](http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-04-07/u-s-book-sales-fell-1-8-last-year-trade-group-says-update1-.html) ↩

-

9

[http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/15/the-passion-of-steve-jobs/](http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/15/the-passion-of-steve-jobs/) ↩

-

10

[http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE63B2J720100412](http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE63B2J720100412) ↩

-

11

[http://gizmodo.com/5443895/e+ink-is-dead-pixel-qis-amazing-transflective-lcd-just-killed-it]([http://gizmodo.com/5443895/e+ink-is-dead-pixel-qis-amazing-transflective-lcd-just-killed-it) ↩

-

12

There are ways around this for the Kindle but they require a certain amount of computer savvy, patience, and access to a computer. ↩

-

13

[http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/jacketcopy/2010/01/apple-ipad-kindle-ibooks-amazon.html](http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/jacketcopy/2010/01/apple-ipad-kindle-ibooks-amazon.html) ↩

-

14

[http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/apr2010/tc20100412_516320.htm](http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/apr2010/tc20100412_516320.htm) ↩

-

15

[http://www.businessinsider.com/henry-blodget-kindle-sales-now-a-shocking-35-of-book-sales-when-kindle- version-available-2009-5](http://www.businessinsider.com/henry-blodget-kindle-sales-now-a-shocking-35-of-book-sales-when-kindle- version-available-2009-5) ↩

-

16

[http://www.switched.com/2010/04/16/apple-rejects-pulitzer-prize-winning-cartoonist-for-ridiculing/](http://www.switched.com/2010/04/16/apple-rejects-pulitzer-prize-winning-cartoonist-for-ridiculing/) ↩