Wandering through the Louvre after losing his first French Open, Andre Agassi was dumbstruck, he recalls in his memoir, by “a painting from the Italian Renaissance” of “a young man, naked, standing on a cliff.” The man hugs a tree limb with one arm. With his other arm he clutches a woman holding two infants over a chasm while an old man, “perhaps his father,” Agassi conjectures, clings to the young man’s neck, clasping “a sack of what looks like money.”

The painting is not Italian but French, not Renaissance but Romantic; it is Anne-Louis Girodet’s Scene of the Flood, from 1806. But never mind. The analogy is what’s important: Agassi’s father, burdensome and grasping, hanging on the shoulders of Agassi, who, vulnerable, exposed, bears the impossible weight of expectations.

The sight of the picture is among several uncanny details in a book in which Agassi’s life unfolds almost like a tale preordained, a clue-strewn riddle of self-discovery laid before him, decades in the unraveling. By memoir’s end, the tennis player has finally solved the riddle, opening a model charter school in the worst part of Las Vegas, his hometown, for disadvantaged children to receive the education he never had but always wanted, and settling down with the woman he had dreamed of years before when she was, not just for her opponents but also for him, unconquerable. He calls her Stefanie, another child prodigy of an impossible tennis father—Steffi Graf.

“It’s destiny,” his coach, Brad Gilbert, had predicted about their marriage at a time, just after Agassi won his first French Open in 1999, when Graf would hardly speak with him. “Only two people in the history of the world have won all four slams and a gold medal—you and Steffi Graf. The Golden Slam. It’s destiny that you two should be married,” Gilbert explained cryptically, then scribbled “2001—Steffi Agassi” on an airline brochure.

As prophesied, the two did marry, in 2001, Agassi having wooed his silent, reticent fellow superstar by saying he hated tennis, a refrain to which the memoir incessantly returns. In response, Graf gave him “a look that says, Of course. Doesn’t everybody?,” convincing Agassi that she was definitely his soul mate. They shared, along with preternatural physical gifts and competitiveness, an understanding of the downside of a tennis career and a determination not to repeat with their own children what had been inflicted on them. Oh yes, and he thought her legs weren’t bad, either.

Finally, Agassi comes to love tennis, which had been a life forced on him, but now had given him a wife and, with the school, something to play for other than just himself or his father’s approval. “From punk to paragon” is how Bud Collins, the tennis commentator, described Agassi’s public transformation—the pigeon-toed teen brat in stone-washed denims, gambler’s shades, and a Mohawk who becomes a philanthropist, philosopher, and statesman. “To my thinking,” Agassi writes,

Bud sacrificed the truth on the altar of alliteration. I was never a punk, any more than I’m now a paragon…. Transformation is change from one thing to another, but I started as nothing…. I was like most kids: I didn’t know who I was, and I rebelled at being told by older people…. What people see now, for better or worse, is my first formation, my first incarnation. I didn’t alter my image, I discovered it.

Which is the (albeit convenient) parable of this remarkable and quite unexpected volume, one that sails well past its homiletic genre into the realm of literature, a memoir whose success clearly owes not a little to a reader’s surprise in discovering that a celebrity one may have presumed to know on the basis of that haircut and a few television commercials hawking cameras via the slogan “image is everything” emerges as a man of parts—self-aware, black-humored, eloquent.

Agassi’s collaborator was J.R. Moehringer, the author of an excellent memoir, in the reading of which Agassi says he escaped the pressures of impending retirement in 2006 and discovered, as he has put it, “the power that existed in someone’s story.” Moehringer graciously but conspicuously declined to share credit for the book, guaranteeing that he would receive it. No doubt much of the book’s immediacy and structural ingenuity, and perhaps the whole literary invention of Agassi’s mature and affecting image, are due to him—likewise (the persuasive simulacrum of) Agassi’s voice, his curiosity and abiding wonderment. On the verge of an ill-fated first marriage to the actress Brooke Shields, Agassi finds that Shields, as inspiration to get herself in shape for the wedding, has taped a photograph to her refrigerator door of the woman she wished to resemble, the “perfect woman with the perfect legs—the legs Brooke wants.”

Advertisement

He stares at the photograph, as he did at the Girodet, in amazement.

It’s Graf.

The Wimbledon tournament beginning this month has Roger Federer defending his championship again, after losing in 2008 to Rafael Nadal, the Herculean Spaniard, who until last year had also been invincible at the French Open in Paris, the great endurance test of professional tennis, fought on the red clay of Roland Garros. Before last year Nadal had won four French titles and topped that off with the Wimbledon crown. Then in 2009 he succumbed in the fourth round, improbably, to a gangly, rising journeyman Swede, Robin Soderling, who at Wimbledon once annoyed him by mocking Nadal’s helpless tic of picking at his shorts between points. A likable, shy young man happiest before the altar of his Playstation when not beating the bejesus out of tennis balls, Nadal plays an unprecedentedly violent game, heavy on topspin and sweat, the perfect foil to Federer’s effortless one. They’re artful opposites, akin to Agassi and Pete Sampras. The Nadal–Federer rivalry has become the most fascinating in sports, only more so now because it cannot go on much longer with Federer turning thirty next year, antique in tennis years.

Nadal, in the way Sampras was to Agassi, has been both an obstacle and a gift to Federer. About Sampras’s retirement after the 2003 US Open, Agassi says:

Our rivalry has been one of the lodestars of my career. Losing to Pete has caused me enormous pain, but in the long run it’s also made me more resilient. If I’d beaten Pete more often, or if he’d come along in a different generation, I’d have a better record, and I might go down as a better player, but I’d be less.

Federer would no doubt say the same about Nadal, rivalry being the heart of sports, and, for athletes, no matter how bitter or fierce, something strangely akin to love: two vulnerable protagonists for a time lifted up not despite their differences but because of them.

The art of tennis, somewhat less obviously, depends on how players shape points by moving the ball around the court to make it arch and zig, devising patterns that from a spectator’s perch map crisscrossing lines. The fan’s pleasure, after a particularly good exchange of shots, stems from redrawing those lines as a memory, every point, like every creative mark on a page with a pencil, being slightly different. Within sameness, there is variety, artists have proved. Athletes have, too.

There is also something beautiful about the great rivalries like Federer–Nadal or Sampras–Agassi that involves sportsmanship, harkening back to the game’s gentlemanly roots. The sport, like golf, although checkered by unlovely characters in recent decades, clings to a mythology of grace; and Agassi’s revelation in his memoir that for a short while he tried crystal methamphetamine, then lied to tennis officials after testing positive for it, caused a stir when the book was published, not because it was remotely as germane to his on-court performance as steroids have been to baseball or football players (if anything it caused him to lose), but because the vestigial reputation of tennis, even in its current multibillion-dollar, multinational corporate form, is not like baseball’s or football’s.

It is still exemplified by players like the German baron, Gottfried von Cramm, who won two French titles during the 1930s. A Terrible Splendor, by Marshall Jon Fisher, focuses on a match between Cramm and the American Don Budge played on Centre Court at Wimbledon to contest the 1937 Davis Cup between Germany and the United States. A jockeying five-setter, remembered by both players as one of the finest ever (and somewhat hopefully described by Fisher as the best), it is his excuse to recall engagingly an era when tennis was still clothed in starched white slacks and a painstaking, Arthurian civility, but was changing. Cramm is the archetype: high-born, dashing, honorable even to the extreme of sacrificing an earlier Davis Cup championship for Germany by calling a point against himself after making an invisible mistake. Modest and erect, the mere sight of him apparently made a group of Hollywood royals abort their plan to walk out of a tournament in Los Angeles in 1937 where he was playing because they believed him to be Hitler’s representative. Afterward, an abashed Groucho Marx told Budge: “When I saw that man, I just felt instant shame at what I was supposed to do.”

In fact, the Nazis imprisoned Cramm, who, although occasionally married (briefly, later, to Barbara Hutton), was known to be gay and, more to the point, indiscreet about his hatred for fascists. Organizing a petition of players on Cramm’s behalf, Budge is a Preston Sturges–style hero in this tale—homely but endearing—a far greater champion than Cramm although duller. Hence, Fisher turns to Bill Tilden, tennis’s Babe Ruth, the sport’s original bad boy and superstar, for a rival to Cramm on that score.

Advertisement

The opposite of Agassi, born into prosperity and idleness, a lonely, gay, orphaned teen, Tilden took up tennis seriously only in his early twenties, determined suddenly to become the greatest in the world, an absurd goal, even in that era, which he achieved through meticulous study and sheer force of will. For a time, he dominated the game in a way that even Federer has never quite equaled. He hardly lost a match in major tournaments or the Davis Cup for years running, nor any (recorded) match at all in 1924, and won fifty-seven games in a row against stiff competitors. Combined with his arrogance and cantankerousness, his baiting of umpires and linesmen, his flouncing manner, his tanking of games against lesser opponents so that, theatrically, he could then storm back to win matches—his whole general profligacy on and off court thrust tennis onto a new stage.

He was still great into his early fifties but would end up twice jailed for infractions with minors, then scrounging for cash as a teacher on public courts because private clubs shunned him. (He had blown several fortunes earlier on Broadway flops he wrote and starred in.) He later recalled about the tennis players of his youth: “They played with an air of elegance—a peculiar courtly grace that seemed to rob the game of its thrills…. There was a sort of inhumanity about it,” he added. “I believed the game deserved something more vital and fundamental.”

And as Fisher writes, “that is exactly what he gave it.”

But it would not be until Agassi’s youth, in the 1980s, when the sport became big business, with a carnival appetite for underage champions. Agassi’s story is in many ways typical and typically American. He is pushed by his immigrant father, Mike, a captain, or usher, at a casino in Las Vegas whom Agassi portrays as a sort of comic Caliban, tearing thick bouquets of black hair from his nose and hanging himself from a homemade noose to relieve chronic neck pain. As a poor boy, Mike had fetched stray balls for British and American soldiers playing tennis on courts in Tehran. The experience, paired with seeing a wheelbarrow of silver dollars rolled one day onto the court at the Alan King tournament in Las Vegas, caused him to imagine the game as the short route to prosperity, and his four children as the means to get there. He saw the new age in tennis dawning.

Andre describes the machine his father devised to fire balls at him at 110 miles per hour, day after day, when he was only seven. Hit a million balls (literally a million, his father wished, at a rate of 2,500 a day) and you won’t lose. Sometimes yanked out of school to practice, Andre learned to hit on the short hop blistering returns. By eight, he became Mike’s ace in the hole. When an unsuspecting Jim Brown, the football great, showed up at the local club one day, Agassi’s father wagered him that he couldn’t beat Andre.

“Don’t do this, Jim,” the club owner warned. Brown growled. “Guy’s asking for it.” “You don’t understand,” the owner insisted. “You’re going to lose.”

Of course Agassi won, but even then, as a little boy, he wondered about the pride, fear, and humiliation that his father’s gamble stirred in him. While he “never questioned” his father’s love, he wished it had been “softer, with more listening and less rage. In fact, I sometimes wish my father loved me less.”

Instead, Mike loved, much less, Agassi’s older brother, Philly, a good player who lacked the killer instinct, making him just “a born loser” to his father and, therefore, himself. “By rights this should make Philly a basket case,” Agassi muses. “At the very least it should make him resent me, bully me. Instead, after every verbal or physical assault at the hands of himself and my father, Philly’s slightly more careful with me, more protective. Gentler.”

Raising the ante, Mike shipped Andre off to Nick Bollettieri’s loveless tennis academy in Florida, where homesickness and a system rigged to churn out dimly educated tennis champions caused him to rebel. He got his ears pierced, started drinking, smoking pot, picking fights, busting curfew, chewing tobacco, generally acting “like an ass,” as he puts it, and also failing classes, to which Bollettieri cynically responded that he was not made for school because he has “a hard-on for the world.”

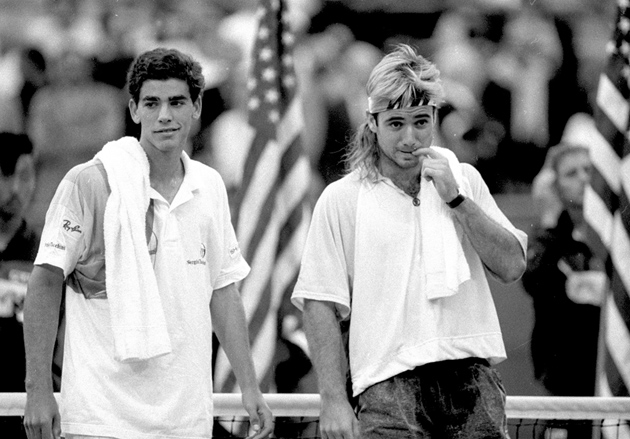

So by the time he wins his first tournament as a pro in 1987, in Brazil, he is a strutting Id, a lightning rod (“a haircut and a forehand,” sniffs Ivan Lendl), all the more so after he bucks tennis whites and decides, with Nike’s backing, to make demin his signature look. “They call me a rebel, but I have no interest in being a rebel, I’m only conducting an everyday, run-of-the-mill teenage rebellion,” he reflects. “Subtle distinctions, but important,” he writes, adding, “I’m flattered by the imitators, embarrassed, thoroughly confused. I can’t imagine all these people trying to be like Andre Agassi, since I don’t want to be Andre Agassi.”

Soon he takes to wearing a ridiculous hairpiece to disguise the truth that he’s balding. When he reaches the finals at the French Open in 1989, he panics about the hairpiece falling off, then loses the final of the US Open, then another final in Paris, then even the will to win, until out of the blue, against a strong field of grass court players, he captures Wimbledon in 1992. His father is silent when Agassi phones to celebrate.

“You had no business losing that fourth set,” is all Mike musters, but then Agassi hears the faint sound of sobbing.

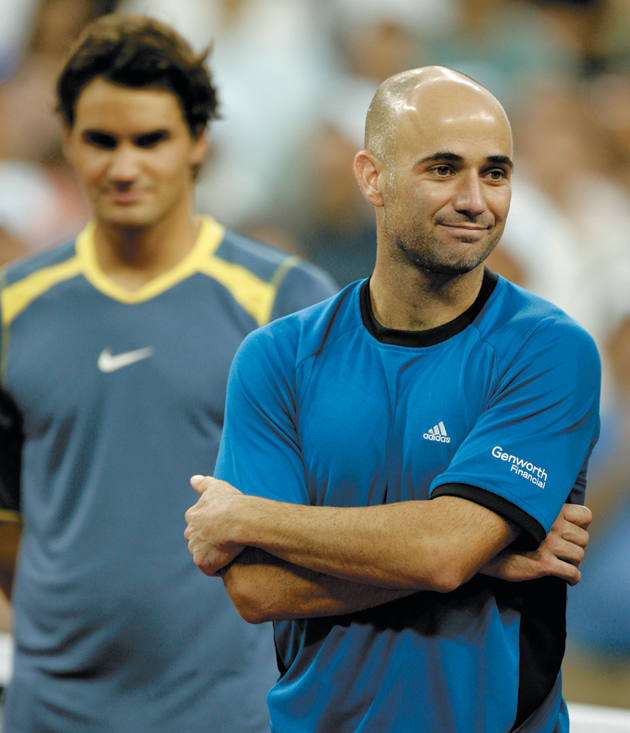

At a tennis exhibition this March—a doubles match to benefit victims of the Haitian earthquake, featuring Agassi and Nadal versus Sampras and Federer—the usual banal banter players feel obliged to concoct to entertain the crowd turned nasty when Agassi alluded to a story he relates in his memoir about Sampras tipping a valet only $1 at a restaurant in Palm Springs years ago. Agassi also wrote in the book that while he found the media’s story line of the “diffident Californian versus the brash Las Vegan” “horseshit,” Sampras and he were indeed different in that, for Sampras, “tennis is his job, and he does it with brio and dedication,” whereas Agassi is distracted by life. “I envy Pete’s dullness,” is how he phrased it. “I wish I could emulate his spectacular lack of inspiration, and his peculiar lack of need for inspiration.”

Not surprisingly, Sampras looked aggrieved in Palm Springs. Agassi’s casual cruelty, rationalizing Sampras’s greater success by needling him about his cheapness, may be just old rivalry flaring up, but it is also a reminder that all memoirs, even the ones that seem most open, serve as apologies for their authors, who invariably invent a literary self in the writing. Agassi’s book makes Sampras, Bollettieri, and Shields into shallow players, and by contrast makes heroes out of the bumptious Gilbert and Gil Reyes, Agassi’s trainer, who deliver him from a mid-career collapse in the 1990s.

He describes how they were there when the afterglow of victories had begun to fade. He found himself blowing up during matches and alienated from Shields, who staged their wedding like a Broadway musical, for cameras, and made Agassi wear elevator shoes, then a cowboy hat and denim shirt to ride on horseback into a barbecue for friends and family the next day. He laments how he had “played this game for a lot of reasons,” and “none of them has ever been my own.” Gilbert lectured him about “all those people out there, all those millions who hate what they do for a living” and “do it anyway,” but a wrist injury and drugs only accelerated his slide, from number one in the world to number 141.

Then he came back, with Gilbert’s and Reyes’s support, swallowing his pride and entering the low-level “Challenger” tournaments, where players operate their own scoreboard by flipping numbered plastic cards between games and the winner’s check is $3,500. “There is clarity and nobility in just being a journeyer,” Agassi decides. It is 1999 and he is nearly twenty-nine.

“It’s so typical in sports,” he notes. “You hang by a thread above a bottomless pit. You stare death in the face. Then your opponent, or life, spares you, and you feel so blessed that you play with abandon.” In the final of the French Open that year, against a poised Andrei Medvedev, a Ukrainian to whom Agassi had once given advice that he now finds employed against him, he rallies from near defeat in a classic cliffhanger, the kind he at times almost seemed, like Tilden, to orchestrate. Agassi is “terrified by how good this feels.” It is yet another step that brings him to the revelation that now “I play and keep playing because I choose to play. Even if it’s not your ideal life, you can always choose it. No matter what your life is, choosing it changes everything.”

He continued to win through 2004, one of the most inspired second acts in modern sports. A child of the wooden racket age, with a brother-in-law, Pancho Gonzalez, who was winning championships during the Berlin airlift, Agassi at the 2005 US Open encounters Federer strolling on court “looking like Cary Grant” minus the ascot. Briefly, after nabbing the second set, Agassi imagines winning their match, and thinks Federer might imagine it too, until, in the tiebreak of the third set, Federer “goes to a place that I don’t recognize. He finds a gear that other players simply don’t have.”

An era had passed, a new one begun. Agassi’s last victory was at the US Open in 2006, over an erratic but charmingly extroverted young Cypriot, Marcos Baghdatis. A wild five-set match, it required all of Agassi’s guile, ending with both players writhing in agony on adjacent locker room tables. It is Agassi who rises first, joyous and grateful.

“Enjoy, savor, take it all in, notice each fleeting detail,” he had told himself during the match, a sage now, “because this could be it, and even though you hate tennis, you might just miss it after tonight.”

This Issue

June 24, 2010