The Pregnant Widow begins as a beautifully poised, patient comedy of manners, in the tradition of the nineteenth- century English novels that Martin Amis’s college-age hero, Keith Nearing, is reading; then, in the last third, the narrative skips ahead and thins out and speeds up and starts to destroy itself joyously, like one of Jean Tinguely’s self-wrecking sculptures—or like civilization itself in the twenty-first century. It’s as if As You Like It, after carefully staging explorations of love and gender in a sylvan setting, were to knock itself out in a violent, messy, urban free-for-all right out of Animal House. In this respect alone I was reminded of Gravity’s Rainbow, in which the main theme, entropy, causes the book itself to give up on being, intermittently, a fairly traditional historical novel about World War II and to go to pieces, to run down, and the main character, Slothrop, to vanish.

Amis has definitely given us an example of imitative form. In the first two thirds of the book there are even many direct references to Shakespeare’s comedies, and young women are accused of being blokes or even “cocks,” and the feminist revolution is piggybacked on the earlier sexual revolution. It all recalls Shakespeare’s games with androgyny, his boys playing girls playing boys. Toward the end of the book Keith suggests to the deeply ambiguous Gloria Beautyman that she dress up as Viola or Rosalind: “She’s pretending to be a boy. Passing as a boy. Wear a sword.”

After dwelling on a single visit to an Italian castle for a tense, glorious summer in 1970 and working out all the erotic possibilities (the characters even play chess much of the time), the narrator nosedives through the succeeding decades up to the present, losing hopes, loves, friends, and even the lives of the people he (or possibly she) loves along the way in a reckless, pell-mell casting aside of almost everyone he had ever cherished. Very lifelike. That’s what aging does to you.

Philip Larkin had declared that “Sexual intercourse began/In 1963,” and by 1970, when The Pregnant Widow begins, the youngsters have added copious four-letter words to their repertoire as well as saucily direct comments, appalling nicknames, and obscene erotic refinements. At one point Keith thinks: “The word fuck was available to both sexes. It was like a sticky toy, and it was there if you wanted it.” In spite of all these liberties and acquisitions, the youngsters still seem naive, self-hating, and snobbish.

In his memoir, Experience, Amis credits Mrs. Thatcher in the early Eighties with having cut through the British obsession with class of those earlier days: “Whatever else she did, Margaret Thatcher helped weaken all that. Mrs. Thatcher, with her Cecils, with her Normans, with her Keiths.” It’s no accident that Amis has used here the plebeian name Keith, as he has in his past fiction. In The Pregnant Widow Keith, in talking with his girlfriend Lily, tries to defend his Christian name by saying at least it’s better than that of their friend Timmy:

“It’s impossible to think of a Timmy ever doing anything cool. Timmy Milton. Timmy Keats.”

“…Keith Keats,” she said. “Keith Keats doesn’t sound very likely either.”

In Experience Martin Amis, impressed by his posh classmates at boarding school, looks up his own name: “Martin was the forename of half the England football team; and when I looked up Amis in a dictionary of surnames I was confronted by the following: ‘Of the lower classes, esp. slaves.'”

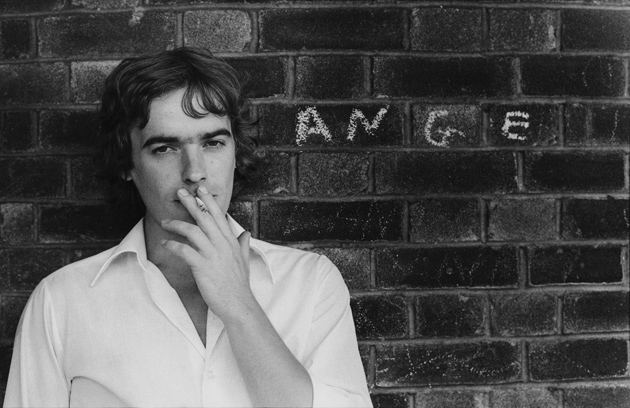

It’s too bad that Keith Keats isn’t more promising as a name, since our Keith wants to be a poet. After a brief flurry of publishing in his early twenties he gives it up and indeed Keith Nearing, we might say, resembles Martin Amis if he hadn’t had the drive and talent to become a writer. Keith is addicted to sex, or thoughts of sex, as most men are, with this difference: male writers are also obsessed with dreams of glory and mental games of literary composition. Writers spend free nonsexual moments thinking about their writing and careers. Amis has said that he enjoys writing, that doing it is an active pleasure for him, and in The Pregnant Widow that pleasure is plain for all to see, even though the book is often world-weary in tone and the main character (for that’s what Keith must be called in fairness since, improbably, he turns out not to be the narrator) is so often in poor shape when it comes to sex. Keith has a longish period when women aren’t attracted to him and he’s condemned to a bilious celibacy; in Experience Amis tells us of the real-life counterpart to this dreadful but mercifully short sexual dry spell.

Not that this novel is veiled autobiography. It’s really more a kind of alternative memoir about a lesser person, one who doesn’t have the stamina and imaginative fire to write. In that way it’s a bit like Look at the Harlequins!, in which Nabokov provides the gullible reader with a fictional autobiography of a Russian cad who has a string of unsuccessful marriages and had seduced a nymphet. In the same vein Amis in The Pregnant Widow is an orphan and thereby sheds his famous real-life father Kingsley, the beloved and eccentric main character in Experience. Keith Nearing’s biological parents, we’re told, are of the servant class.

Advertisement

In The Pregnant Widow there’s a large cast of young characters and few adults to supervise them (one chapter is titled “Where Were the Police?”). Keith is at the castle with his girlfriend Lily, who has, alas, become something like a sister to him; when he has sex with her he often has to fantasize she’s someone else, even with her verbal help and cooperation. At one point she pretends to be Scheherazade, the shatteringly beautiful sister of the owner of the castle. Scheherazade is so young she has only just grown into her beauty and hasn’t yet become fully conscious of it: “There was too much collusion in the softly rippled lids—collusion in the human comedy. The smile of a beautiful girl was a sequestered smile. It hasn’t sunk in yet, said Lily. She doesn’t know.” At one point Scheherazade sets up a secret rendezvous with Keith until he gets drunk and starts ranting against God; she, as it turns out, is religious (or at least her adored absent fiancé, Timmy, is).

More obliging though also more sadistic is Gloria Beautyman, a triumphant narcissist who looks at herself and declares that she loves herself: “Oh, I love me. Oh I love me so.” There’s something mysterious and odd about her, though, which only becomes clear at the very end of the book. Then there’s Adriano, the perfect Italian aristocrat who’s rich and flies his own helicopter and plays rugby with I Furiosi and speaks several languages and is capable of deep emotions and is altogether perfect—except he’s four foot ten inches tall. (He gets called “Tom Thumb” behind his back, a consolation to Keith, who is worried about his own height and has to stand on a drainpipe in order to kiss his girlfriend in the street.) There’s the older, wiser gay man Whittaker, who’s in love with a very young, difficult Libyan named Amen. Various other young men and women drop into the castle and the narrative, including a viciously uninhibited woman nicknamed “The Dog.”

This is a book that is highly conscious of being a book. Keith, of course, is reading all those novels; at one point he says, “Timmy’ll be along in a chapter or two.” The action often echoes the plots of the novels he’s reading. “If Keith paraphrased Mr. Knightley, would Scheherazade realise, at last, that she was in love with him?” Elsewhere, Keith is poolside, perusing Peregrine Pickle: “Peregrine had just attempted (and failed) to drug (and ravish) Emily Gauntlet, his wealthy fiancée….” Later Keith will try to drug his girlfriend Lily so that he can ravish the beautiful and wealthy Scheherazade (he fails).

There are many subtle parallels between books and reality. But for Keith the whole experience is literary:

The Italian summer—that was the only passage in his whole existence that ever felt like a novel. It had chronology and truth (it did happen). But it also boasted the unities of time, place, and action; it aspired to at least partial coherence; it had some shape, some pattern, with its echelons, its bestiaries.

By contrast, life—the life he goes on to live—“is made up as it goes along.” This contrast between the rare, well-made, already novelistic experience and the more common, messy, improvised shapelessness of ordinary existence explains the shift from the tidy social comedy of youth to the baffling weirdness of age—and the exploded shape of this book.

Martin Amis is very funny and accurate about aging. In the first few pages we encounter this:

When you become old…When you become old, you find yourself auditioning for the role of a lifetime; then, after interminable rehearsals, you’re finally starring in a horror film—a talentless, irresponsible, and above all low-budget horror film, in which (as is the way with horror films) they’re saving the worst for last.

But Amis has no single theory about age. It’s much too interesting (and neglected) an experience to sum up once and for all. Here’s an observation about it:

Advertisement

As the fiftieth birthday approaches, you get the sense that your life is thinning out, and will continue to thin out, until it thins out into nothing. And you sometimes say to yourself: That went a bit quick. That went a bit quick. In certain moods, you may want to put it rather more forcefully. As in: OY!! THAT went a BIT FUCKING QUICK!!!… Then fifty comes and goes, and fifty-one, and fifty-two. And life thickens out again. Because there is now an enormous and unsuspected presence within your being, like an undiscovered continent. This is the past.

Over the years Amis has learned how to notate a superbly comic speaking voice; getting it down on paper is comparable to a good composer’s skill in scoring heteroclite sounds never before made by concert instruments. That in this passage a solemn tone brackets a middle section of Borscht Belt humor illustrates perfectly Amis’s mastery of the sudden shifts in register that are the peculiar genius of English prose—nearly impossible to translate into Romance languages, for instance.

The nasty depredations of age are items Amis loves to tick off in a comic, lip-licking list of horrors:

And it all works out. Your hams get skinnier—but that’s all right, because your gut gets fatter. Your eyes get hotter—but that’s all right, because your hands get colder (and you can soothe them with your frozen fingertips). Shrill or sudden noises are getting painfully sharper—but that’s all right, because you’re getting deafer. The hair on your head gets thinner—but that’s all right, because the hair in your nose and in your ears gets thicker. It all works out in the end.

Here the rhetorical effects of repetition, the insistence that everything is all right, the parody of cheerfulness in the service of disgust—all these figures dramatize the tragicomedy of one’s “late period.”

Perhaps Amis’s most striking meditations on age and time in this “snuff film” we’re all starring in, this move from Club Med (frolicking in the sun) to Club Med (the medicalized final moments), derive from his analysis of age as the one remaining class system. If Thatcher got rid of poshness and feminism got rid of masculine hegemony and political correctness downgraded the status of the white race, then all that remains is age:

As we lie dying, not many of us will have enjoyed the inestimable privilege of being born with white skin, blue blood, and a male member. Each and every one of us, though, at some point in our story, will have been young.

The people who are currently young, Amis predicts, will rebel against caring for the growing percentage of the population that is old; they “won’t like the silver tsunami, with the old hogging the social services and stinking up the clinics and the hospitals, like an inundation of monstrous immigrants. There will be age wars, and chronological cleansing….”

The tone of these comments is rendered in Amis’s hilarious essay style. Sometimes I wonder why writers who are witty and restless and worldly in their essays become dull narrators, inexhaustibly sequential (“and then, and then”) in their novels, grazing every last thing in view. Wasn’t it Valéry who said that when he read in a novel sentences such as “The Marquis went out at ten o’clock,” he was tormented by how arbitrary the specific time was and realized he could never stoop to the dreariness of fiction? It’s as if some essayists go from being fiery, high-stepping horses to digesting bovines, patiently chewing every last bit of grass, once they turn to fiction. If Proust remains the supreme mind in fiction, it may be because he began his novel as an essay or rather a Platonic dialogue between his mother and himself about Sainte-Beuve. And George Eliot, another truly intelligent novelist of ideas, turned to fiction only after she’d written numerous essays on fiction. Neither of them merely masticates.

I mention this notion of the essayistic in fiction not because I want pages and pages of ideas transcribed in novels but as a corrective to the American assumption that true novelists are rough-and-tumble brutes getting it all down—redskins instead of palefaces, to use the old distinction. Camus said that American writers were the only ones in the world who weren’t also intellectuals. I suppose what I’m saying is that writers shouldn’t lose twenty points of IQ when they turn away from essays to fiction. They should remain true to whatever it is that deeply engages them in writing, no matter what the genre.

Amis certainly knows how to present dramatic scenes with dialogue and terse descriptions of action. But he has also always known how to analyze action, usually from a comic point of view, how to place it in a chilling- hilarious historical or social setting. Few contemporary novelists would dare to write, as Amis does here, “We live half our lives in shock, he thought. And it’s the second half.” But this isn’t some random apothegm; it is a dramatic thought, provoked by the life situation of the main character and attributed to him; it certainly is not an Olympian idea delivered from on high. Late in the novel the narrator asks:

What kind of poet was Keith Nearing, so far? He was a minor exponent of humorous self-deprecation (was there any other culture on earth that went in for this?)…. He was of the school of Sexual Losers, the Duds, the Toads, whose laureate and hero was of course Philip Larkin.

The idea that humorous self-deprecation is unique to the British is not only true (try modesty in an American job interview and see how far it gets you) but also pertinent to Keith’s portrait.

This funny essayistic voice is the same one we hear in Amis’s amusing and accurate literary essays, collected in The Moronic Inferno: And Other Visits to America. In discussing the fame and material success that came to Norman Mailer when his first novel was published, Amis writes: “After an equivalent success, an English writer might warily give up his job as a schoolmaster, or buy a couple of filing cabinets.” In discussing the last days of Truman Capote, Amis talks about how the diminutive novelist was hounded constantly by Lawrence Grobel, the author of Conversations with Capote: “Towards the end, his life appeared to be a bleak alternation between major surgery and Lawrence Grobel.”

In The Pregnant Widow, however, the wit and the analysis are used to open up the story, to take a single idyllic summer and trace out its consequences in numerous lives and through four decades. Many of the themes in this new novel echo those sounded in Amis’s very first, The Rachel Papers: sexual hunger joined to sexual insecurity; Latin tags and literary references used as erotic window-dressing; a twenty-year-old protagonist let loose in a foreign setting where he stalks British birds (Spain in the case of The Rachel Papers); intense if ambiguous class consciousness.

Amis has always dealt with lads or cads, amoral pigs (Money) or spotty kids on the make (The Rachel Papers) or a hateful, petty mobster (Keith Talent in London Fields) or an evil, competitive novelist, Richard Tull, determined to destroy his successful rival Gwyn Barry in The Information. He understands that evil exists in the world and he knows how to portray it in all its self-justifying, self-pitying luxuriance. When I teach creative writing I have to give a very exact assignment to get my students to sketch a bad person, to render any character other than one who is kind, sensitive, and politically correct. Only once they break the good barrier do these young writers begin to understand the possibilities of fiction. Martin Amis learned this liberating lesson early and well. He knows how to give his characters a short memory of their own misdeeds and a long memory of their grievances. He knows how they can justify any horror they’ve committed—and even add a little grace note of self-congratulation to the gory recital.

Keith Nearing is more lad than bad in The Pregnant Widow—and by the end of the book he has clearly matured, if that means to have grown bleak with insight and depressing wisdom. Amis’s readers will be delighted by this return to form—that is, a new depth brought to familiar themes. And no one can deny the superb writing throughout, the attention to detail and to language lavished on every sentence. At one point close to the present Keith wonders if beauty has gone out of the world; if it did, it has just reentered literature through this strange, sparkling novel.

This Issue

June 24, 2010