The year 1968 was one of heartbreak and division, marked by assassinations, war, and war protests. Campuses were riven with contending passions. But at two schools there were oases of agreement, uniting students, faculty, and alumni. Harvard and Yale had stellar unbeaten football teams. Yale’s was the more glamorous, with quarterback Brian Dowling, who had not lost a game since the seventh grade. His team-mates called him “God,” and soon the whole campus was doing it. The team’s black running back, Calvin Hill, was hardly less celebrated—he would go on to a famous professional career.

There were some hints of a world outside of football. The Harvard tackle, Tommy Lee Jones, had as his roommate Al Gore. The Yale tackle, Ted Livingston, had George W. Bush as his roommate. But on the field, all was comity and pride. When the two teams finally met at the season’s climax, they both remained unbeaten. At the end of the game, Harvard was down eight points with three seconds to go. It scored from the eight-yard line, in an upset tie celebrated ever after by both sides.

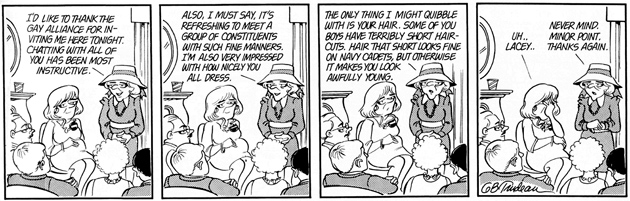

Observing from the sidelines was a quiet undergraduate who drew a comic strip for the Yale Daily News. In the strip, called “Bull Tales,” he impishly mocked the great football heroes, turning Brian Dowling into the thick-headed B.D. and showing Dowling and Hill with their jersey numbers. He gave B.D. a feckless roommate, the pencil-nosed Mike Doonesbury. (Doone was a nickname at Trudeau’s prep school for a doofus, and Trudeau confesses there is a touch of autobiography here.) He also took sly shots at Yale’s non-football heroes, making the president, Kingman Brewster, into President King and the school chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, into Reverend Scot Sloan. The strips were crudely drawn, but Trudeau already showed his amazing ear for the way people talk. B.D. did not look like Brian Dowling (or much like a human being at all, with his clumsy box nose) but he spoke the way their classmates did. Still, only an extraordinary talent scout would have suspected that this entirely parochial school spoof had the makings of a great national comic strip.

That talent scout was Jim Andrews. He and his Notre Dame classmate John McMeel had just started their newspaper syndicate, Universal Press, in a basement. Without big names to begin with, Andrews scouted college papers for good writing on politics, or culture, or religion. In the process, he came across “Bull Tales,” met Trudeau, and persuaded him to become their first comic strip. Trudeau started drawing for Universal Press while doing graduate work in graphic arts at the Yale Art School. In the process he learned to draw. His master’s thesis, with the photographer David Levinthal, was a book, Hitler Moves East, enacted by model tanks and soldiers. The strip’s later drawings of the Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars, remarkably forceful in their depiction of battle, draw on the work he did for Hitler Moves East. Trudeau continued doing graphics work (he designed the book jacket for my edition of Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday).

One of Trudeau’s first tasks at Universal was to get his characters off campus. In a takeoff on the film Easy Rider, he sent Mike Doonesbury and his radical friend Mark Slackmeyer out on a motorcycle with sidecar to “find America.” On the way, they pick up a runaway wife and mother, Joanie Caucus. This is an early example of the way he exfoliates his dramatis personae, eventually making him Dickensian in his range of characters. In this fortieth-anniversary volume, he draws ninety continuing characters in a double fold-out of two pages, tracing all their interconnections. This does not include cameo appearances by presidents and other celebrities, including Donald Trump.

His characters not only proliferate, they grow (and grow old). Joanie goes from being a commune member to a graduate of Berkeley Law School, where she meets Virginia Slade and her boyfriend Clyde, who become regulars in the strip; then, after graduation, she becomes a staff member for Congresswoman Lacey Davenport (who later came to resemble Millicent Fenwick of New Jersey), whose dithering husband also joins the strip; later Joanie marries Rick Redfern (modeled on Bob Woodward), a rival of pompous journalist Roland Hedley (modeled on Sam Donaldson), with whom she has a child, Jeff. She works for the Justice Department until the Bush administration comes in and fires her. She is now at retirement age (and a grandmother), but she cannot retire, since Rick Redfern is a victim of the shrinking newspaper business and Jeff is in college (he will join the CIA on graduation).

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Joanie’s abandoned daughter J.J. (Joan Jr.) has grown up and marries Mike Doonesbury, the man who, years ago, had picked up Joanie with his motorcycle. But J.J. is as restive as her mother, so she runs off with Mike’s yardman, Zeke Brenner (a little Chatterley here), before she becomes a performance artist (at the peak of that fad) and earns a genius grant for outlandish art. While still with Mike, she bore him a daughter, Alex, who goes off to study at MIT. Since Alex hates Zeke, her mother’s boyfriend, she bonds with her grandmother—back to Joanie. Take that, Mr. Dickens.

The characters are now in their third generation, and we have lived with them through four decades of turbulent times—wars, scandals (Watergate, S and L, “Koreagate,” Iran-contra, Katrina, and others), and political campaigns, many of which Trudeau covered as closely as any journalist while catching the essence of each era in unfailingly funny ways. Three generations of young people have grown up with the Trudeau characters. My children as youngsters ate in a little annex to our dining room in Baltimore, which had stacks of Doonesbury comic books, and they devoured them while eating. My daughter became a grade school “libber” to imitate Joanie Caucus.

One of my sons, when in grade school, came with me to New York, where we stayed in an apartment the syndicate kept for its writers when they were in town. Trudeau, still living in New Haven, was staying there too. He said he hoped he would not keep us up by working all night. It turns out that, in the middle of the probes into Frank Sinatra’s connections with the mob, Sinatra’s lawyers had threatened a suit if Trudeau kept up his ridicule of the man. He had to cancel a whole week’s strips and replace them in a single night. My son asked if he could stay up and watch the creative process. Trudeau said, “Sure.” In the morning, I greeted a haggard Trudeau on his way out the door with a large cylinder under his arm. “Did you finish the strips?” “No, only four, but I have to get them right away to the airport.” There are couriers for that, I said; but he assured me he would not let them out of his grip until he absolutely had to. Then he would come back, take a nap, and finish the rest.

That shows the challenge of working as close to events as Trudeau does. One of the marvels of his work is its continued timeliness. When he is not on top of the news, he is ahead of it—sometimes so far that he has to scrap a strip until its predictions come true. At other times, an editor will cancel the strip because it jumps the gun.

There have been other comic strips that dealt with politics, but they did so sporadically, and as one-trick diversions—Al Capp satirizing the welfare state with his schmoos, Walt Kelly turning Senator Joseph McCarthy into Simple J. Malarkey—but Trudeau has reflected on politics at a depth and with a breadth no one else has achieved. No wonder he won the first Pulitzer Prize given to a comic strip (in 1975). When Nixon bombed Cambodia without telling Congress that he was invading another country, Trudeau sent his terrorist character Phred to the bomb site. When he sees a couple standing American Gothic–style before a leveled museum, he asks if this happened during the secret bombing of Cambodia. The man says it was no secret. “I said ‘Look Martha, here come the bombs.'” Nothing could say more succinctly that many of our national security secrets are not meant to deceive the enemy, but to keep Congress and the American people in the dark about what our government is doing in our name. (I liked this strip so well that I asked Trudeau for the original, and it now hangs on my wall.)

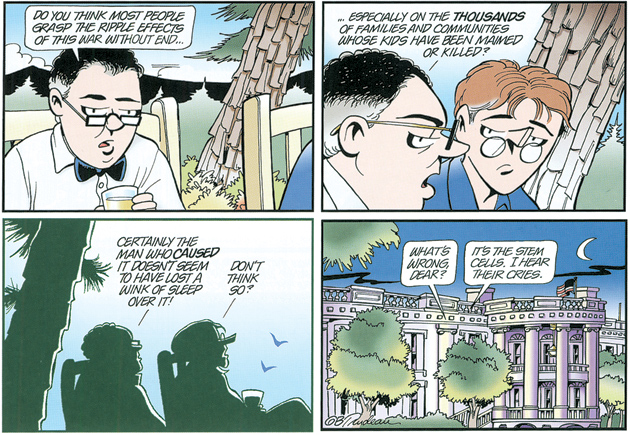

Over and over Trudeau pinpoints governmental absurdities. After Mike and a friend have discussed the casualties of the Iraq war, in a strip that ran in 2005, they wonder if the dead cause any anguish in the President. The last panel shows voices coming from the White House in the night. Laura asks, “What’s wrong, dear?” and Bush answers, “It’s the stem cells. I hear their cries.” Another strip shows a soldier coming home. His wife asks who that is arriving with him. He says it is the terrorist following him home, as Bush had claimed they would.

Trudeau has guided us through many presidencies. He often uses a heraldic emblem as a stand-in for the incumbent president or other prominent politicians—a “point of light” for George W. Bush, a waffle for Clinton, a feather for Quayle, a bomb for Gingrich. He sent a journalist spelunking into Reagan’s brain to find where all those fantastic things were made up. He at first presented George W. Bush as an asterisk, referring to his “election” by the Supreme Court, then (as the President went to war) as a grandiose Roman helmet, one that got battered and dented as time went on.

Advertisement

One has to admire the skill with which Trudeau brings in new characters, whether based on real people or made up for the purpose, by connecting them with his core characters. Zonker Harris, one of the members of the original commune, has an Uncle Duke (modeled on Hunter S. Thompson), who acquires an Asian woman as translator in China, called by him “Honey,” who follows him devotedly through his zany adventures. When Joanie divorces Mike, he marries Kim, a Vietnamese orphan seen years before being adopted by a Jewish family in California. Decade after decade, more and more characters join the show, while regulars keep cycling back into the new conditions of the time. (Slate has a useful FAQ that describes any character you may have lost track of.)

The strip’s characters become so real that they enter into “reality.” Trudeau gave the commencement address to the Berkeley law class that graduated Joanie. His rock star Jimmy Thudpucker was scheduled at actual concerts. (Jimmy has fallen on hard times—now he composes ringtones for telephones.) In 1978, House Speaker Tip O’Neill called Trudeau to have Lacey Davenport cancel her hearings into “Koreagate.” When Lacey crusaded against a Palm Beach law that required servants to carry their identification papers, the Florida legislature knocked it down in what was called the “Doonesbury Bill.” After Millicent Fenwick’s death, her family sent Trudeau the “ladylike pipe” that he had given Lacey in the strip. In December 1992, Working Women named Lacey Davenport and Joanie Caucus as role models for women.

Trudeau saw his characters through the AIDS crisis, with the Lacey campaigner Andy Lippincott dying of it in 1989. This is an example of something that seems impossible to bring off in a comic strip, the treatment of sadness with pathos. When Dick, Lacey’s husband the bird-watcher, finally sights a Bachman’s Warbler, he has a massive coronary just before taking its picture. But at the last minute he clicks the shutter, and with his expiring breath sighs “Immortality.” The next strip just shows birds of all kinds flying above his body in a gentle salute. When it comes time for Lacey’s death (after Millicent Fenwick had died), Dick appears to guide her through the passage from life. As the forms dim and then disappear, Dick assures her they are in heaven. Lacey, independent as ever, says, “What hideous drapes.” Dick responds: “Shh! Mrs. God picked them out.”

Most comic strips run out of creative energy after their initial inspiration. Trudeau has just kept improving, year after year, in part because he stays so close to changing events. He still has his ear for the way young people talk through all the varying slang fashions (perhaps helped by his children). At any rate, he has never been better than in the last six years. B.D., who always wore his football helmet when he was not wearing an army helmet in Vietnam, goes to Iraq as an aging National Guard adjunct and his tank is hit by an IED. The strip blacks out, and when he emerges from the darkness, he is seen for the first time without a helmet of some kind—and we find his hair is white at the temples. But that is the least shock—he has also lost a leg. The beloved original character of the strip is tragically maimed.

Trudeau was now facing the supreme test for a comic strip artist. How do you laugh and cry at the same time? B.D. descends into depression and alcoholism, but he is steadied by a funny vet rehab specialist (himself an amputee). Trudeau has now spent years visiting veterans’ hospitals and rehabilitation centers. In 2006, Washington Post reporter Gene Weingarten followed him on these rounds, inside and outside Washington. As always Trudeau has caught the special lingo these men use with each other. Weingarten was uncomfortable at the suffering he saw, but Trudeau was at ease and knew how to put the men at ease.

It was not simply that he knew how to empathize with the veterans. When Weingarten visited Trudeau’s wife, Jane Pauley, she confided that he had her ordeal to help him understand theirs. She had gone through a horrendous period of mental anguish near the same time B.D. was doing so. She described this in her book Skywriting. Only after being diagnosed as bipolar did she get the lithium treatment she needed. She told Weingarten that Trudeau would deny the connection, but “He’s writing about mental illness…. He’ll want to say no, but it’s hard to argue with. Isn’t it?”

While keeping up with his characters on other fronts, Trudeau has stayed with the recovering B.D. and his counselor Elias. B.D.’s wife, the bubble-brained actress Barbara Ann Boopstein (Boopsie), has been forced to grow up as she too lives through B.D.’s ordeal, gaining strength herself as she strengthens him. And as usual, B.D. heals as he helps others heal—including Melissa, a woman soldier raped by her own troops, and then Leo DeLuca (Toggle), a metal rock musician who lost an eye and part of his speech function, with whom the MIT student, Alex, has fallen in love.

Trudeau has always been able to take a situation and develop its possibilities over a long arc. Sometimes this has led to slapstick, as in the antics of Uncle Duke, whose drug seizures make the top of his head flip open to let bats fly out or release Mini-D, who is his Id. Sometimes it has led to gentle mocking of do-gooders, as in some of Lacey Davenport’s polite crusades. But he has never developed a situation more movingly or powerfully than in recent years with his treatment of wounded veterans. A great modern American history course could be taught using this volume of collected strips, stretching from Watergate to Afghanistan.

This Issue

November 25, 2010