How to write about Mexico’s drug war? There are only a limited number of ways that readers can be reminded of the desperate acts of human sacrifice that go on every day in this country, or of the by now calamitous statistics: the nearly 28,000 people who have been killed in drug-related battles or assassinations since President Felipe Calderón took power almost four years ago, the thousands of kidnappings, the wanton acts of rape and torture, the growing number of orphaned children.

For reasons they themselves probably do not completely understand, the various Mexican drug clans and organizations responsible for so much bloodshed have acquired a liking for public attention, and to hold it they have developed a grisly theatrical performance of death, a roving display of grotesque mutilations and executions. But for all the constant innovations, one horrifying beheading is, in the end, much like the next one. The audience’s saturation point arrives all too quickly, and news coverage of the war, event-driven as all news is, has become the point when people turn the page or continue surfing.

We, the people in charge of telling the story, know far too little ourselves about a clandestine upstart society we long viewed as marginal, and what little we know cannot be explained in print media’s standard eight hundred words or less (or broadcast’s two minutes or under). And the story, like the murders, is endlessly repetitive and confusing: there are the double-barreled family names, the shifting alliances, the double-crossing army generals, the capo betrayed by a close associate who is in turn killed by another betrayer in a small town with an impossible name, followed by another capo with a double-barreled last name who is betrayed by a high-ranking army officer who is killed in turn. The absence of understanding of these surface narratives is what keeps the story static, and readers feeling impotent. Enough time has passed, though, since the beginning of the drug war nightmare1 that there is now a little perspective on the problem. Academics on both sides of the border have been busy writing, and so have the journalists with the most experience. Thanks to their efforts, we can now begin to place some of the better-known traffickers in their proper landscape.

1.

In 1989, an up-and-coming drug trafficker called Joaquín Guzmán, and known generally as El Chapo or Chapo—which is what short, stocky men are called in Guzmán’s home state of Sinaloa, on the northwest coast of Mexico—picked a fight with some of his business associates in Tijuana. Four years later, the estranged associates sent a hit team to Guadalajara, where Chapo Guzmán was living. According to records of the investigation, the Tijuana team was supposed to intercept Guzmán on May 24, 1993, as he arrived at the airport on his way to a beach vacation, but the murderers appear to have confused Guzmán’s white Grand Marquis with one owned by the burly Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, cardinal of Guadalajara.

As the unfortunate cleric pulled up to the curb, the Tijuana hit men opened fire. (According to some versions, Guzmán had arrived at the airport by then, and engaged in a shoot-out with the killers.) The cardinal died on the spot, and even though this was to become one of the most scandalous murders of the century, a subject for endless conspiracy theories, the hit team managed to get on the next commercial flight to Tijuana. No one has ever been tried for the crime. Guzmán’s comment on the day’s events, before he packed his bags and went on the run, was “Esto se va a poner de la chingada,” or roughly, “Things are going to get really fucked now.”

Guzmán’s take on the situation was correct: he fled south, unimpeded by a trail of “Wanted: Joaquín Guzmán” posters everywhere he went, but he was captured in Guatemala and deported to Mexico in a matter of days. Guzmán didn’t foresee his own long-term prospects, though. At the time of the cardinal’s murder he was merely one of the more ambitious Sinaloa traffickers plying their trade along the Pacific coastal states and the northern Mexican border. Seventeen years later—eight of which were spent in a Mexican prison, from which he escaped in 2001, reportedly in a laundry van—Guzmán may be more embattled than ever, but he is also the most powerful trafficker on earth, or certainly the most influential.

We owe Guzmán’s prophetic statement, and the details of his flight, to his former business administrator, as quoted by Héctor de Mauleón, a novelist and essayist who has just published a biography of Chapo Guzmán in the Mexican magazine Nexos. De Mauleón has pieced together his account of Guzmán’s life from court records of his convicted former bodyguards, associates, relatives, and enemies. We learn a great deal about this very rich big-time thug: his canniness, his insecurity about his height, his lavish wedding a few years ago to a Sinaloa beauty queen.

Advertisement

But what we mostly understand here, as in de Mauleón’s parallel biography of Arturo Beltrán Leyva—Guzmán’s former associate turned bitter enemy, who was killed in December—is his influence at the highest levels of the Mexican government. Throughout these records army generals provide Guzmán with information, police officers provide security, major airports are run by his allies, and the dark suspicion grows steadily that cabinet members in several administrations, including the current one, are also on friendly terms with him.

It’s not that Guzmán has influence whereas other traffickers do not; it’s that every trafficker has a great many appointed officials and elected politicians on his payroll but Guzmán has more than the rest. The most distressing conclusion one can draw from de Mauleón’s articles is not that President Calderón’s war on drugs is being lost but that it may not even be fought. The sampling in the court records would suggest that each high-level arrest and killing claimed by the government as a victory—notably that of Guzmán’s former friend Arturo Beltrán—is a consequence of skillful intelligence work not by the government but by the traffickers, who systematically turn each other in to their government contacts—and are often freed by contacts working for the other side, as happened to Beltrán:

On May 7, 2008, the Federal Preventive Police set up a checkpoint at km 95 of the highway between Cuernavaca and Acapulco. The police had just received information leaked to them by [a major trafficker] Arturo Beltrán was about to pass through there. The regional director of the Federal Police was in charge of coordinating his capture…. Five suspicious vehicles [approached]. The police agents signaled them to stop. The convoy members opened fire. [Arturo Beltrán Leyva managed to escape, but his enemy, counting on that possibility] had provided the police with addresses in Cuernavaca in which Beltrán Leyva might hide. The police inspector who…had received the leaked information called…the Federal Police’s chief of antidrug operations and told him: “We’ve located various addresses [for Beltrán Leyva]…we’re mobilized [mobilizados] and ready to enter.

The antidrug chief cut him off: “Stop everything. Return immediately to Mexico City.”

Beltrán’s luck—or his contacts—finally ran out in December 2009, when he was surrounded and killed by a Navy commando team, which was presumably selected on the supposition that, having had very little to do with the drug war until that point, it was less likely to be infiltrated by traffickers. The question left floating in the air by these records and testimonies, and by common experience, is this: If the army and the national intelligence agencies are so generally infiltrated as to be completely unreliable, and if both local and federal police forces are so corrupt and dangerous that we frequently have reason to fear them as much as we do common criminals, then what is the use of having them? Or as several participants wondered at a recent series of round-table meetings convoked by Calderón: How can the security forces be controlled or safely replaced? The question is particularly pointed now that the federal government has fired 3,200 policias federales—one tenth of the total force—presumably for reasons of corruption. The last time a comparable firing took place was in the late 1990s, when the first elected mayor of Mexico City fired three hundred police officers for reasons of corruption, and the city immediately witnessed an unprecedented increase in violent robbery and kidnapping.

2.

When general outrage broke out in Mexico in February, following the wanton killing in late January of fifteen youths at a birthday party in the northern border city of Juárez, Calderón did not help matters by declaring that, like most of the violent deaths in Juárez, these latest murders had been the result of a “gang fight.” He was distressingly wrong in this case—the young people had no connection to the drug trade. Still, most murders in Juárez are, indeed, the result of gang warfare. The murder rate in Mexico City is eight per 100,000, comparable to Wichita, Kansas, or Stockton, California. The overall murder rate in Mexico is fourteen per 100,000. But in Ciudad Juárez it is 189 per 100,000. And as in Tijuana, Reynosa, or Nuevo Laredo—other border cities also afflicted by runaway violence—all but a very small number of the Juárez victims are, in fact, involved in one way or another in the drug trade.

Advertisement

The border is the crossing point for some $300 billion worth of legal commercial traffic, which, ever since 1994, when a free trade agreement between Mexico and the United States went into force, has grown exponentially. The war among drug traffickers began over the right to move drugs through the border cities. One would have thought that traffickers moved their goods by foot, in the dark, through desert territories. In fact they still do, in great quantities, but they move their goods most efficiently and in far greater volume past US customs inspectors in broad daylight. Illegal substances travel in SUVs, double-semi trucks, or beat-up cars, packed with merchandise, disguised as eggs in crates, stuffed into teddy bears, melted into candy bars, or tamped into hollowed-out chairs.

It’s easy to see why arrangements regarding access points to the United States would be unstable: the bigger the city and the larger the volume of legal trade, the easier it is for contraband to go unnoticed. Most cocaine is grown and processed in South America, and much of what is smuggled into the US passes through Mexico. Most marijuana and opium poppy crops are grown on the Pacific coast, and controlled by the old families in Sinaloa, Guzmán’s foremost among them, but growing is easy. The hard part is getting the product to market, and in this effort border cities are the prize rich enough to go to war for. What’s less easy to understand is how a trade that for decades had flourished with nothing more than the standard gangland kidnappings and killings has in the last half-dozen years erupted into the nightmare symbolized by Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso.

There is, first of all, the setting. In his excellent introduction to Drug War Zone, a collection of oral histories of participants in the drug world, Howard Campbell describes Juárez for us:

The local landscape provides myriad spaces for imaginative traffickers. Rugged mountains, creased with sharp canyons and arroyos, overlook vast deserts. The lowland, downtown section of El Paso winds along the Rio Grande…. Drug traffickers can easily ford the river and disappear into the maze of rural back roads scattered across El Paso County (one of the largest in the United States), and from there enter Interstate Highway 10, which connects the east and west coasts of the United States….

To the east of downtown Juárez, new commercial and residential sections and hundreds of maquiladoras loom on the horizon, and to the south and west a boundless web of impoverished colonias (poor neighborhoods) has replaced farm and desert lands. Just as El Pasoans can see the factories of their sister city, Juarenses can see the skyscrapers of El Paso from many parts of the city—the two border communities are inextricably linked….

Furthermore, migration to Juárez from Mexican states to the south brings a huge reserve labor army to the colonias and urban barrios, and local government is unable to deal with this influx. There is a virtually limitless supply of unemployed workers ready and willing to make good money by driving or walking loads of drugs across the border or by serving as a stash-house guard or a hit man. Smugglers have little difficulty adapting socially or communicating in Spanish, English, or Spanglish on either side of the bilingual, bicultural border. The enormous maquiladora industry and related El Paso long-haul trucking industry provide the heavy-duty eighteen-wheelers and every possible storage facility, tool, equipment, or supply needed to package, conceal, store, and transport contraband drugs.

Campbell’s central contention, stated in the title of his book, is that the whole idea of a Mexican drug smuggling enterprise, or problem, is untenable: a land so thoroughly bilingual, bicultural, miscegenated, and porous—despite the arbitrary demarcation of a border and the increasingly weird and futile efforts to seal it—can really only be studied and understood as a united territory and a single problem. This is an idea so breathtakingly sensible as to amount to genius,2 and one wonders how many deaths could be avoided if policymakers on both sides of the Rio Grande shared this vision and coordinated not only their law enforcement efforts but their education, development, and immigration policies accordingly.

What we have in the place of collaboration is the shattering loneliness of Juárez. In the 1990s, when young women began to disappear from the poorest shantytowns in the city, and then turned up like so much waste matter, bruised, raped, mutilated, and dead, police officers laughed in the faces of the distraught parents who appealed to them for help. Reporting on the story, I stood one afternoon on a gray hill covered in gray dust above a gray squatter settlement and looked across the river at the faux-adobe office buildings of El Paso. Around me the tumbleweed jittered in the breeze, and plastic supermarket bags and odds and ends of clothing fluttered everywhere, as if all the trash in all of Mexico had beached itself at this spot. A few hundred yards downhill lived the sister of one of the disappeared girls, and for all the outreach by NGOs and solidarity groups concerned with the murders, she seemed as isolated and vulnerable as it was possible for a young woman to be.

Speculation has been never-ending about who was responsible for the murder of those girls—there were several dozen of them, tangled among the statistics for hundreds of other, more random female homicides. It was always clear that the police were somehow involved—the grotesque laughter at the police station, the switched clothing on a couple of bodies eventually returned by police to the bereaved families, the systematic destruction of evidence, all pointed in their direction. But it seemed unlikely that lowly police officers would have the political backing to engage on their own in sick serial murders and remain unpunished, even as a worldwide campaign mounted to protest the killings.

I remember asking back then if a likely culprit might not be the lord of Juárez, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, who was the most powerful trafficker of his day. Who else, in the course of doing regular business, could buy off enough politicians, police commanders, and justice officials to guarantee himself immunity under any circumstances? Conceivably, Carrillo Fuentes or his minions had developed a fascination with death that went beyond the strictly professional. Several of the girls had one breast sliced off, and in a shack in the desert some weird graffiti seemed also to have ritual meaning.

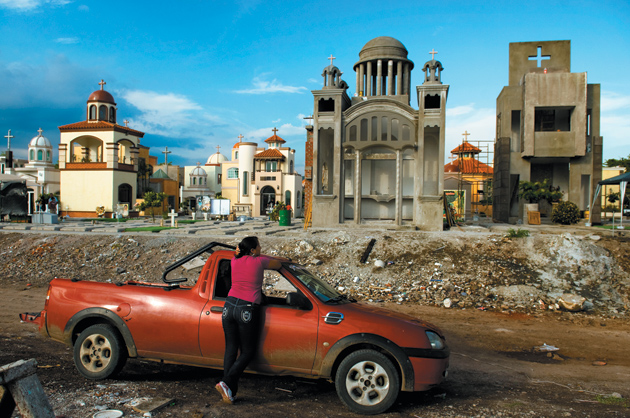

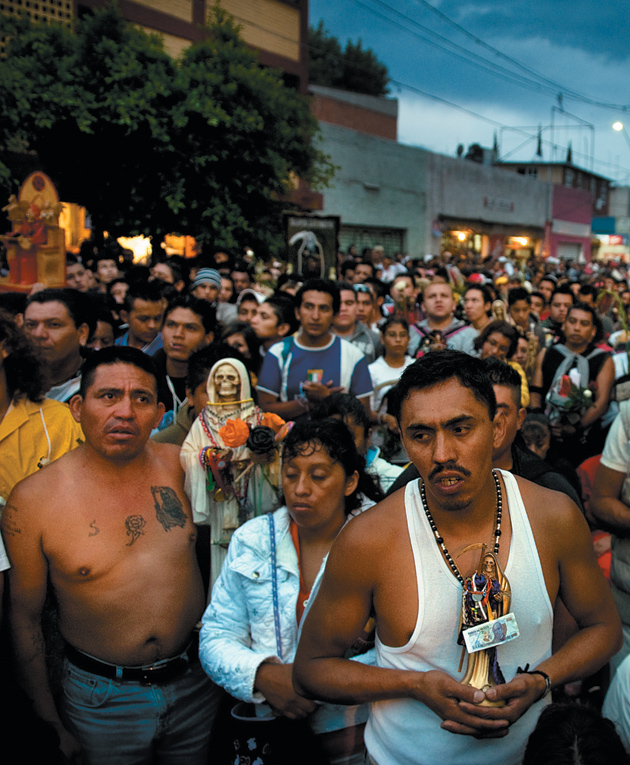

None of us reporters understood much then about the new religious cults mushrooming in the drug world—notably the Santa Muerte, or Holy Death, a Halloweenish figure identical to the hooded skeleton who makes frequent appearances in biker art. Her cult has spread well beyond the jailhouses where she is revered, and now that altars to the gloomy skeleton are everywhere in the country and we have heard of young migrant girls from Central America being killed and offered to the Santa Muerte by the particular branch of the drug mafia devoted to human trafficking, there is more reason to wonder if the current traffickers’ obsession with nauseating forms of murder did not start back then.

3.

Carrillo Fuentes, the lord of Juárez, died in 1997. He was given the wrong kind of sedative—perhaps even accidentally—while recovering from plastic surgery in a boutique Mexico City hospital, and his death left the Juárez plaza (meaning a combined drug distribution territory and supply route) wide open. Chapo Guzmán of course tried to move in immediately following Carrillo Fuentes’s murder (or before, if he was behind the fatal injection), but so did a trafficker who, unusually, comes not from the Pacific coast state Sinaloa but from Tamaulipas, which lies across the country on the Gulf of Mexico. His name is Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, and for quite a few years he held the profitable monopoly of all the trafficking in Tamaulipas, whose border cities Reynosa, Matamoros, and Nuevo Laredo are collectively the largest commercial crossroads in the world. Nuevo Laredo is, consequently, the most lucrative plaza in Mexico; some eight thousand trucks pass the US customs inspection checkpoints at Laredo every day. Cárdenas, a man of ambition and keen business sense, baptized what was then just a gang, calling it the Cartel del Golfo (Cartel of the Gulf).

The Cartel del Golfo’s operations prospered wonderfully, so much so that, according to several reliable accounts, their members drive around the border city of Reynosa, particularly, in black SUVs painted with the initials CDG. But Cárdenas was arrested by Mexican police in 2003 and extradited to the US, where he was sentenced to twenty-five years in February of this year. He left a legacy in his home state, though. All the traffickers before him had relied on their own gatilleros, or hired killers, to enforce their law, but in the late 1990s Cárdenas figured out the logistical and intelligence advantages of hiring military men—particularly highly skilled military men who had been trained to fight him—as his own private defense force. That is how the rogue drug gang the Zetas was born. Today it is a collection of former police agents and Central American army special forces, gang members, and what amounts to indentured killers, all led by a group of Mexican former special antinarcotics forces who destroyed all the existing narco codes of honor and rules of engagement.

It should come as no surprise that the Zetas are now at war with their parent group, the Cartel del Golfo. There are predictable rhythms and sequences in the growth and development of illegal groups, as Juan Carlos Garzón points out in a lucid study, Mafia & Co.: The Criminal Networks in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia. Garzón examines the drug groups in these three countries as if they were so many bacteria, and studies the way they divide and form new colonies:

Criminal structures are increasingly adopting a network form. They have been moving away from cumbersome—almost bureaucratic—organizations that tried to monopolize illegal economies, toward the configuration of cells that specialize in certain parts of the production chain or in a specific market (like the protection market).

The big boss who used to give all the orders no longer exists…. The real leader is the person who has the contacts and the connections, the person who has developed a significant concentration of relationships….

Most crime organizations have lost their leader at some point in their history but this has not led to their disappearance as an organization. Generally, what happens is that in the absence of the top leader, a process of fragmentation occurs. The successor doesn’t often manage to keep the same cohesive structure, and several possible scenarios emerge. If a capo is captured or killed by the government forces, a situation of instability is created in which various factions attempt to preserve themselves individually. In this framework, the mid-level commanders will begin to compete for the leadership of the organization (as is happening, for example, with the Gulf Cartel). Some structures will try to become independent. Others will be taken over by larger groups…. Some will form alliances to try to maintain a minimum level of cohesion so they can reorganize…and others will be prepared to offer themselves to the highest bidder….

The ever-fluctuating war among the constantly fragmenting and multiplying drug clans and families is, among other things, a culture war, one being fought by the old campesino marijuana-growing and smuggling families along the Pacific coast against the wholesale traffickers of the Gulf of Mexico, who grow nothing.[^ ]:It’s also a war with, on one side, Pacific coast criminals who have a romantic vision of themselves as renegade outlaws—and who commission old-timey biographical ballads about themselves (narcocorridos) to spread that vision, like this one about Guzmán’s famous escape from prison on January 20, 2001:

It was January 19

That Chapo shouted “Presente!”

When they took the roll call,

But the plot was already laid

For when they called him next day,

He didn’t answer at all.

3

On the other side are former members of the Mexican military establishment in the east, whose taste in music, as far as one can tell from the narcovideos frequently put up on YouTube, runs to techno and reggaeton.

Pacific coast smugglers like Chapo Guzmán have yet to catch up with the Zetas’ ability to intercept the conversations of even the lowliest politicians along the Tamaulipas border and their delight in chest-thumping (they appear to have been the first to use trucks to block major thoroughfares, sometimes just for the hell of it). If recent news reports are correct, the Zetas also use antiaircraft weapons and satellite trackers. The traffickers from Sinaloa rely on backroom alliances with local politicians to keep the business quiet and safe—one can only think with envy of Chapo Guzmán’s Rolodex. The Zetas show no sign that they have ever heard of the word “compromise” and seem bent on a direct challenge to all authority.

The Sinaloa traffickers’ cult of a rural trickster hero, Jesús Malverde, is in equally stark contrast with Gulf coast worship of Holy Death. The Zetas seem modern and the Pacific coast gangsters old-fashioned, but at the moment we have no way of knowing who is winning, partly because the Zetas are so out of control and partly because the clan leaders on the Pacific coast who used to form an alliance are busily trying to kill one another, as are the Zetas and their former masters in the Cartel del Golfo.

Properly speaking, as Garzón points out, the Zetas are not really a trafficking group. Osiel Cárdenas ran the Cartel del Golfo’s trafficking operations and hired the Zetas to provide the muscle. The Zetas are an enforcement enterprise, with franchises that specialize increasingly in kidnapping, extortion, holdups, and human traffic. On Mexico’s southern border they lie in wait for the freight trains used by US-bound migrants from Central and South America—and apparently, from as far away as China as well. If the pollero, or people smuggler who guides the migrants in their passage through Mexico, does not have an arrangement with the Zetas, the helpless migrants are kidnapped, beaten up, raped, extorted. With increasing frequency, the men in the group are forced to work as killers themselves, which would indicate that the Zetas’ branch organizations are growing faster than they can be staffed.

Once they leave the southern border, the migrants head for the United States along routes also patrolled by the Zetas, all the way to Laredo and Reynosa. There is only one train route used by the traffickers on Mexico’s border with Guatemala, yet the Mexican government seems helpless to stop either the migrants or the crimes committed every day against them. On August 23, near the city of San Fernando, some one hundred miles from the US border, the Zetas stopped a bus full of migrants, herded them to a nearby isolated ranch, and, after a confused series of events lasting several hours, executed seventy-two.

Two things are worth noticing about the massacre. The first is that from the traffickers’ point of view, no practical end was achieved by killing seventy-two migrants, who were neither enemies nor hostages about to be rescued. The killers appear to have acted out of rage, on whim, or simply out of tedium or habit. They have terrorized half of Mexico, but criminals who lose all discipline tend not to last very long.

The second noteworthy thing is the Mexican government’s response to the tragedy. According to the first reports published in the newspaper El Universal, troops at an army outpost some fourteen miles from the ranch were notified of the massacre by a survivor, but they did not immediately go to the scene of the crime because, the story in El Universal said, they were afraid of being attacked. The first troops arrived at the scene only the day after the lone survivor alerted them to the massacre. This from a military that has been ordered by its commander-in-chief to wage all-out war on the drug trade.

On September 19, following the murder of its second reporter in less than two years—a young man barely twenty-one years old, who joined the list of the more than thirty journalists murdered or disappeared in Mexico during the last four years4:—the daily Diario de Juárez published an editorial addressed to the “Lords of the different organizations fighting for the plaza of Ciudad Juárez”:

We say to you that we are in the communications business, and not mind-readers. Therefore, as information workers, we want you to explain to us what you want from us, what it is your aim that we should publish or refrain from publishing…. You are, at the moment, the de facto authorities in this city, because the legally constituted authorities in this city have been unable to do anything to prevent the continuing murder of our colleagues, despite our repeated demand…. We do not want more dead. We do not want more wounded nor further intimidations. It is impossible for us to fulfill our duty in these conditions. Therefore, tell us what you expect from us as a medium….

It was a relief of sorts to have someone with a public voice and the authority to do so declare, for the record, that the state is no longer the arbiter of who lives or dies along the border. But the question of who is in charge, who rules, who holds the power is vexing.

An easy conclusion would be that Mexico, or the drug war zone, is in the hands of a failed state. But a failed state does not constantly build new roads and schools, or collect taxes, or generate legitimate industrial and commercial activity sufficient to qualify it as one of the twelve largest economies in the world. In a failed state drivers do not stop at red lights and garbage is not collected punctually. The question is, rather, whether in the face of unstoppable activity by highly organized criminals, the Mexican government can adequately enforce the rule of law and guarantee the safety of its citizens everywhere in the country. This, at the moment, the administration of Felipe Calderón does not seem able to do, either in large parts of the countryside or in major cities like Monterrey. There is little doubt that Calderón’s strategy of waging all-out war to solve a criminal problem has not worked. Whether any strategy at all can work, as long as global demand persists for a product that is illegal throughout the world, is a question that has been repeated ad nauseam. But it remains the indispensable question to consider.

—Mexico City, September 30, 2010

This Issue

October 28, 2010

-

1

Strictly speaking, thirty-nine years have passed since Richard Nixon first targeted drug production and consumption as a priority for his administration. What Nixon then baptized as a “War on Drugs” has since spread from a handful of countries in the Andes, the Mideast, and Asia to every continent, creating law enforcement problems in Canada and devastating already helpless countries like Guinea-Bissou. Since Nixon’s time, however, overall demand for illegal substances, whether agricultural in origin—like heroin, marijuana, or cocaine—or chemical, like methamphetamines, has remained steady. ↩

-

2

The idea is expressed in similar terms by, among others, the experienced and keen-sighted Guardian foreign correspondent Ed Vuillamy, in the title of his roadie book Amexica: War Along the Borderline (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, to be published in November 2010). ↩

-

3

Adan Cuen, “El Corrido del Chapo Guzmán Loera.” ↩

-

4

A horrifying and greatly enlightening report on the state of the press in Mexico is “Silence or Death in Mexico’s Press,” with a preface by Joel Simon, Committee to Protect Journalists, September 8, 2010, available at cpj.org. Following a lengthy meeting on September 22 with members of a joint delegation of the Committee to Protect Journalists and the InterAmerican Press Association, Calderón announced on September 27 that the government was putting in place a long-announced plan to provide physical protection to journalists under threat. Legislation put forward by Calderón to make attacks on journalists a federal crime has been stalled in Congress for two years. ↩