Jimmy Carter is a better man than his worst enemy would portray him as. And his worst enemy, it turns out, is himself. At least, I cannot imagine a more damaging blow to his reputation than he delivers in White House Diary. It confirms the portrait drawn of him in 1979 by his former speechwriter, James Fallows, in a devastating Atlantic Monthly article1 that presented him as immersed in petty details like scheduling who could play on the White House tennis court or typing up the list of classical music selections piped everywhere in the living and working quarters of the executive mansion. Carter now gives us exhaustive records of just such preoccupations. Sometimes the attention to detail can be rather endearing. When Vladimir Horowitz was scheduled to play a recital in the White House, he came the day before to tune the piano and test the room’s acoustics. Carter went down to hear him rehearse and learned that the room was too “live”; the sound needed muffling. At this Carter got down on his hands and knees to help spread rugs around.

Other details get mind-numbing as Carter records them at merciless length. The diary itself is an indictment of the man’s pettiness. He wanted a record of his actions not only day by day but almost minute by minute. He did not simply keep this diary at the end of a day, he says, but dictated it “several times each day.” Long as this book is, it includes only about a quarter of the twenty-one large volumes of the diary he is depositing in the Carter Library. And this is the diary for just his four years as president. He assures us that he limits himself to what “I consider to be most revealing and interesting…general themes that are still pertinent.” One wonders, after this description of his project, why he thinks we should know about each recurrence of his hemorrhoids, how he disciplined his daughter for “a dirty word,” how many arrowheads he and Rosalynn turned up in their frequent forays into the fields around Plains, Georgia, and what flies he tied for his fishing catches.

In the heat of the moment he sets down for all time his reaction to people who peeved him—Scoop Jackson (“acted like an ass”), Harrison Schmitt (“one of the biggest jerks in the Senate”), Russell Long (“a complete waste of time”), Ellie Smeal of NOW (“crazy women’s organization”), Frank Church (an “ass…who ought not be in the Senate”), and Helmut Schmidt (“a paranoid child”).

Carter had personally run everything concerning the governor’s office in Georgia, and he thought at first he could do the same thing in the White House. Relying on a tight team of intimates personally devoted to him—his wife Rosalynn, Jody Powell, Hamilton Jordan, Bert Lance, Stuart Eizenstat, Charles Kirbo, Frank Moore, and Patrick Caddell—he did not think he needed the Washington insiders he had campaigned against. Fallows reminds us that Powell, Carter’s press secretary, said, early on, that “this government is going to be run by people you’ve never heard of.” He trumpeted that if Cyrus Vance should become secretary of state and Zbigniew Brzezinski the national security adviser, he would resign. They did, and he didn’t. This was not the only imprudent braying from Powell. He boasted publicly that at the Camp David conference between Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, Carter had “broken the back of the Israeli Lobby.”2

Carter revels in the fact that Hamilton Jordan traveled incognito to Paris and other European cities to bargain through intermediaries with Iranian Foreign Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh for release of the American hostages being held in Iran. Jordan sometimes used the name Phillip Warren and “wore a wig, mustache, and other disguises” on these feckless missions. This is a comic shadowing of the cake-and-Bible diplomacy of Robert McFarlane and Oliver North in later dealings with Tehran under President Reagan.

Carter’s religious views were unfairly derided by some commentators. He was a sophisticated reader of Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr. But one does wonder at the reliance he put on psychics to get his foreign intelligence. After the CIA briefed him on a plane crash in Zambia, he dictated:

An American parapsychologist had been able to pinpoint the site of the crash. We’ve had several reports of this parapsychology working; one discovered the map coordinates of a site and accurately described a camouflaged missile test site. Both we and the Soviets use these parapsychologists on occasion to help us with sensitive intelligence matters, and the results are unbelievable.

He appends to this entry his own current comment: “The proven results of these exchanges between our intelligence services and parapsychologists raise some of the most intriguing and unanswerable questions of my presidency. They defy logic, but the facts were undeniable.” Later he dictated this: “We had a session in the Situation Room concerning a parapsychology project where people can envision what exists at a particular latitude and longitude, et cetera.” Nancy Reagan was ridiculed for scheduling events on the advice of an astrologer. But Carter’s advisers seem even spookier.

Advertisement

The diary’s record of petty preoccupations belies the great ambition and achievement of Carter’s one-term presidency. He created two new departments (of energy and of education), reversed the policy of supporting dictators if they were anti-Communist, changed world opinion of America as being opposed to human rights, won a SALT II agreement on restricting nuclear arms, wrestled the Panama Canal treaties through a resisting Senate, wrung the Camp David Accords from reluctant Israeli and Egyptian partners, and changed (for a time) the environmental priorities of the country. Though he increased defense spending overall, he cut out unnecessary or dangerous weapons (the B-1 bomber, more aircraft carriers, the neutron bomb).

The problem with Carter’s presidency was that each of these victories was politically damaging to him. The Panama Canal treaties led to electoral losses for all sixteen Republican senators who voted to ratify them, crippling his efforts to recruit Republicans for later programs. The Camp David Accords hurt him with Jewish voters, who thought he had been too favorable to Sadat. His tightening of the military budget made him look soft on communism. His energy retrenchments made him seem to lack confidence in American swagger. His idealism was portrayed as sappiness. He tried to alert people to various urgent issues, but that was seen as a weak surrender to “malaise.” He lost support in Florida by lifting some of the sanctions against Castro’s Cuba.

A good measure of Carter’s problem is the fact that he was farsighted in seeing the kind of energy and ecological mess we are now experiencing. Thomas Friedman pays proper tribute to his response to the oil crisis of the 1970s, when Carter cut back on fuel use in federal buildings, installed solar panels at the White House, promoted tax breaks for wind technology, and regulated gas consumption in vehicles. In Friedman’s words:

Between 1975 and 1985, American passenger vehicle mileage went from around 13.5 miles per gallon to 27.5, while light truck mileage increased from 11.6 miles per gallon to 19.5—all of which helped to create a global oil glut from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, which not only weakened OPEC but also helped to unravel the Soviet Union, then the world’s second-largest oil producer.3

Reagan mocked such measures as a failure of America’s can-do spirit, and when he became president he canceled the tax breaks for energy conservation measures, lifted regulations, and removed the solar panels. Technology developed for wind and solar energy was sold to foreign countries.

Carter lost the support of key Democrats in his base—men like Tip O’Neill and Ted Kennedy—by his refusal to promote traditional liberal public works programs. From his Georgia days he carried over a concern with deficits. In Georgia, his old rival Carl Sanders had called him “the penny-antiest politician I’ve ever come across.” When Carter opposed Kennedy’s health plan because of its cost, he guaranteed that Kennedy would run against him in 1980, cutting further into his liberal base and giving independents their excuse for supporting the third-party candidacy of John Anderson.

After admitting reluctantly and too late that he needed the advice of the Washington insiders he had scorned, Carter did not know how to evaluate or use it. He let David Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger pressure him to admit the Shah of Iran to the US, after he learned that the Shah was “fatally ill with cancer.” This decision, “made with great reluctance,” was one of the causes of the taking of American hostages by student militants. Some months later, when his secretary of state, Cyrus Vance, among others, advised against his feckless effort to rescue the hostages, he ignored them. He sent a force that turned out to be insufficient, and he had to cancel the operation, in which eight men died in a crash, opening himself to the contradictory charges that he was too foolhardy in trying it and too timorous in withdrawing from it.

It is a bit of a mystery why Carter gets so little credit for his major achievements. He had his head so buried in details that he could not inspire others with some overarching vision or enunciation of goals. He wanted accomplishment more than the reputation of an accomplisher. There was a certain smug self-satisfaction in this. Reading the diary entries that smolder with resentment that people did not appreciate what he was up to, I thought of some words that an admirer of Lord Acton wrote of him: “Anyone who can’t find people to understand him must have gone wrong somewhere.”4 The sense of inward gazing and confinement in the diary is reflected in the way Carter moved in his tight little circle of adulators, bringing to mind Alexander Pope’s portrayal of Joseph Addison:

Advertisement

Like Cato, give his little senate laws,

And sit attentive to his own applause.5

It is significant that Rosalynn Carter was happy to escape from Plains when Carter went off to various postings during his time in the navy, and angrily resisted the idea of returning there when he resigned his commission:

She did not agree with Jimmy’s decision to return to Plains. She resented it, argued against it, and even talked about divorce…. Her husband had not asked her opinion about his career change, and she was trapped with three small children and no career of her own. She threatened to divorce Jimmy, but she packed sullenly while her ebullient husband bounced off to New York City to pick up his honorable discharge.6

Carter wanted to be a big frog in a small pond, to keep control over all the details around him, not to expand his horizons or explore different intellectual worlds. I observed Carter the good and Carter the clueless when I served with him on a panel at a Mike Mansfield conference in Montana after he had left the presidency. In the afternoon, he spoke with a small gathering of students, where he was asked what he, as a man once in charge of administering the laws of the land, felt about the fact that his daughter Amy was arrested for breaking the law (she had been in an anti-apartheid demonstration at the South African embassy). He said,

I cannot tell you how proud I am of her. If you students do not express your conscience now, when will you? Later on, you will have many responsibilities—jobs, families, careers. It will get harder and harder to be free to speak out about injustice. Amy was doing that.

The students applauded him vociferously.

But a different Carter showed up that night for a formal speech in a huge arena. It seemed like all of Montana was there. He got up, buried his head in his address, and in a preacherly sing-song droned on and on about “agape love.” I do not remember now if he expressly referred to Anders Nygren’s classic work Eros and Agape from the 1930s, but I am sure he was drawing on it. He undoubtedly read the two volumes, along with Tillich and Niebuhr. But he was not conveying any of the excitement once created by the book. The audience looked around in puzzled ways and then began slipping off toward the exits.

It occurred to me at the time that this must have resembled the Bible classes Carter has taught all his life. He began doing it at the Naval Academy and continued the practice right through his presidency and back in Plains. The diary refers often to his preparation on Saturday for the Sunday class he would be teaching. It is a sign of the press’s embarrassment or ignorance or indifference with regard to religion that we have no good account of what these endless classes contain. I am sure that they involve worthy moral reflections and exhortation.

George W. Bush or Bill Clinton could match that kind of vague religious uplift—but they did not teach classes on the Bible. They did not spend endless hours, year after year, exploring and explaining the sacred text. William Jennings Bryan taught Bible classes—and Clarence Darrow showed us what he would have been purveying. Aside from moralizing, what kind of scholarship goes into Carter’s treatment of the Bible’s many difficulties? Here if anywhere his undoubtedly deep morality and his undoubtedly deep intelligence should have engaged each other. But I find no evidence that he had mastered or ever used the tools of serious Bible criticism. Where his mind and his morals meet, or fail to meet, there seems to be an unexplored hollowness that could explain much that is mysterious about Jimmy Carter.

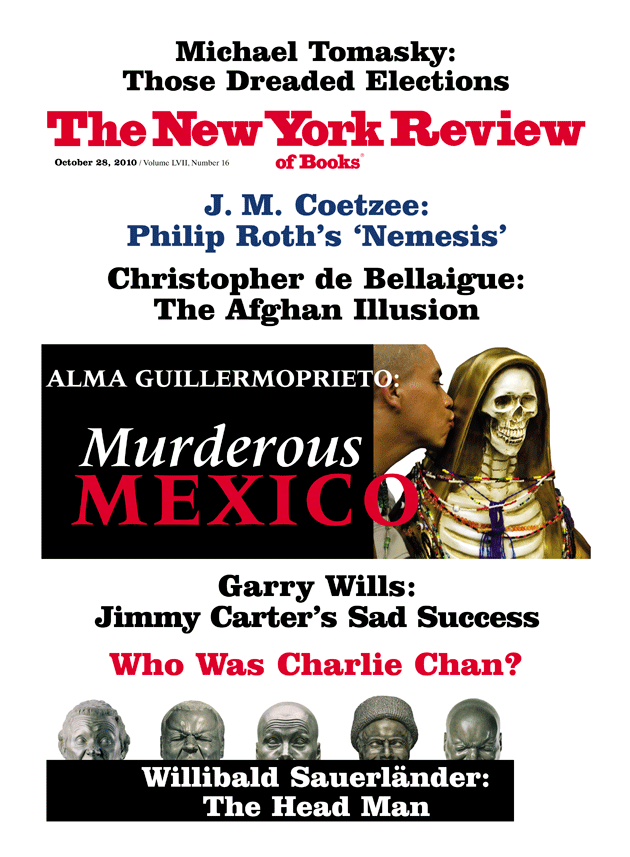

This Issue

October 28, 2010

-

1

James Fallows, “The Passionless Presidency: The Trouble with Jimmy Carter’s Administration,” Atlantic Monthly, May 1979. ↩

-

2

Julian E. Zelizer, Jimmy Carter (Times Books, 2010), p. 82. ↩

-

3

Thomas L. Friedman, Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution—and How It Can Renew America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), p. 14. ↩

-

4

Charlotte Blennerhassett, quoted in Owen Chadwick, Acton and History (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 200. ↩

-

5

Pope, “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot,” lines 209–210. ↩

-

6

E. Stanly Godbold Jr., Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter: The Georgia Years, 1924–1974 (Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 75, 77. ↩