Li Xueren/Xinhua/Corbis

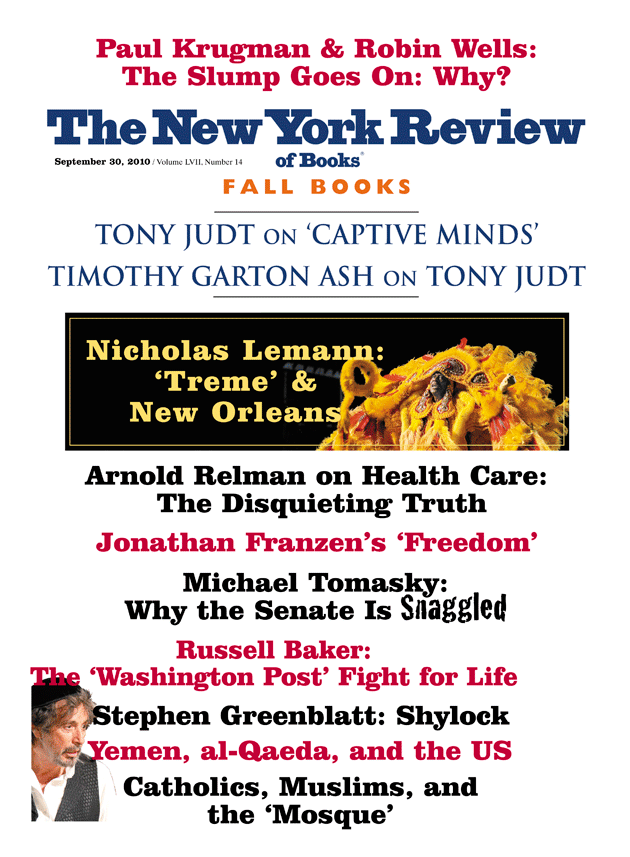

Vice President Xi Jinping (right), who is expected to become China’s next president in 2012, at the plenum of the 11th National Committee of the All-China Youth Federation and the 25th National Congress of the All-China Students’ Federation, Beijing, August 24, 2010. At center is Wang Zhaoguo, a member of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party.

In the next few weeks, an event will take place in Beijing on a par with anything dreamed up by a conspiracy theorist. A group of roughly three hundred men and women will meet at an undisclosed time and location to set policies for a sixth of humanity. Most China watchers will eventually learn that the meeting is taking place and scramble to figure out what is going on, but all the outside world will receive is a terse acknowledgment that it took place and a few gnomic sentences on its outcome. In the weeks that follow, learned scholars will plumb this statement for its deeper meaning, subjecting it to textual analysis and proposing a series of hypotheses that may never be proven.

The gathering will be the Chinese Communist Party’s annual plenum, a session of senior officials who meet every autumn to set the agenda for the coming year. This year, it will focus on economics, especially how to cool down China’s economy without crashing it. But hanging over the plenum will be the giant question of who will run the country into the coming decade. The key question will be if the man tapped to be China’s next leader, Xi Jinping, will get a seat on the Party’s Central Military Commission. Joining this body, which has responsibility for all of China’s armed forces, is one of a series of steps that is supposed to culminate in Xi replacing the current top leader, Hu Jintao, when his second five-year term as president ends in two years.

Some thought that Xi was to join the military commission last year, but he didn’t, and now observers are divided on what that meant—is Xi no longer rising in the Party hierarchy or was that snub unimportant?[^ ]:And what if he doesn’t join the commission at this plenum—is his star falling further, or has the Party changed the rules of succession, with a seat on the commission not as important as had been assumed?

If all of this seems slightly Byzantine, it is. If it also seems incongruous and, well, rather Communist, for a modern, market-oriented country, that is also true. But if it leads you to conclude that this system is in the process of being swept into the dustbin of history, then you would be in good company but very possibly wrong. For much of its history, China’s Communist Party has been written off for dead after its spectacular failures: purges, extermination campaigns, massacres, and famines, to name a few. But each time it has bounced back, often after having changed course in spectacular fashion.

Today, the Party is arguably stronger than ever but few outsiders are aware of its enduring reach. For much of the 1990s and 2000s, the dominant emphasis in stories about China was how un-Communist it was becoming. Western media coverage shifted away from political reporting and toward emphasis on the country’s economic growth or stories about how it was just like us (increasing premarital sex, the development of modern art, combating natural disasters). Everyone acknowledged that China was Communist, but this was said with a wink and a nudge: we all know better.

Emphasizing the changes in China isn’t wrong, of course—the country has changed remarkably, thanks in large part to its jettisoning of many Communist policies and practices. But as Richard McGregor shows in his book The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers, the Party is not increasingly irrelevant; rather, it is at the center of events as varied as shifts in global currency markets, New York stock market listings, and clashes over North Korea. And far from being decrepit, the Party is surprisingly vital, as McGregor convincingly demonstrates in chapters on how it influences China’s economy, military, minority policy, and understanding of history. Although many of its policies are not Communist, the Party is still Leninist in structure and organization, resulting in institutions and behavior patterns that would be recognizable to the leaders of the Russian Revolution. McGregor’s book is also proof that for all of its secretive tendencies, the Party and its power can be usefully analyzed.

Our failure to do so has led to spectacular misperceptions about China, a key one being that the government has been privatizing the economy. Back in the 1990s, for example, the government announced that it would “grasp the large and release the small,” which was taken in Western capitals to mean privatization. In fact, the plan was simply to turn state-owned enterprises into shareholder-owned companies—with the government holding a controlling or majority stake. Many shares were sold overseas to investors eager for a piece of China’s economic growth, but even today almost all Chinese companies of any size and importance remain in government hands.

Advertisement

As McGregor explains in a masterful chapter, foreign investors were often told otherwise by ignorant or unethical Western investment banks and lawyers. Throughout the 1990s and into this decade, prospectuses written by Western lawyers for initial public offerings of China-owned companies consistently fudged the fact that the Party’s Organization Department, not the company’s board of directors, would remain in control of all personnel decisions. One prospectus for a particularly large IPO went so far as to misrepresent China’s political system, stating that the National People’s Congress—a largely rubber-stamp parliament—was the ultimate authority in political issues. It is hard to prove willful intent to deceive, but at the very least Western investment banks were badly misinformed.

Such misstatements might seem trivial or even amusing, but they led to fundamental misperceptions of how Chinese companies are run. All have Party secretaries who manage them in conjunction with the CEO. In big questions, such as leadership or overseas acquisitions, Party meetings precede board meetings, which largely give routine approval to Party decisions. The Party’s overarching control was driven home a few years ago when China’s large telecom companies had their CEOs shuffled like a pack of cards because of a decision by the Party’s Organization Department. It would have been like the US Department of Commerce ordering the heads of AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile to play musical chairs. For the Organization Department, which acts as the Party’s personnel department, it was normal; it often shifts senior Party officials every few years to prevent empire building and corruption.

As for the smaller companies that were “released” by the Party, government control still remains pervasive, if less heavy-handed. Few Chinese companies call themselves private—siying in Chinese—preferring instead the more nebulous term minying, or “run by the people.” What this means is that these companies are run as the manager sees fit, but the manager is often a former official or close to Party circles. Market forces hold sway, but in a form of crony capitalism that leads to local protectionism and corruption. Companies also feel obliged to line up behind government policies, such as its plan to develop China’s impoverished western regions.

Likewise, in the political sphere, the Party runs the government through a parallel structure of behind-the-scenes control. At the very top, senior leaders are members of “leading small groups,” which bring together ministers, experts, and officials in key policy areas. In the case of economics, for example, the body is known as the Communist Party Leading Group on Economics and Finance, which is headed by Premier Wen Jiabao. Hu heads leading groups on foreign policy, domestic stability, and Taiwan.

The leading groups then instruct the relevant ministry what to do—for example, the leading group on economics and finance tells the People’s Bank of China to raise or lower interest rates. The governor of the bank is only a member of the leading group, not independent like Ben Bernanke. These leading groups are the true sources of power in the central government, but like other Party bodies, who serves on them is secret and they are never mentioned in the local media. It is only through the painstaking work of modern-day China watchers that these groups’ membership lists can be discovered.1

Such committees exist down to the grassroots and have power in many other fields, such as academia—meeting a high school principal is fine but the school’s Party secretary almost always has more say. So too the judiciary, in which judges translate court decisions made by Communist Party legal affairs committees into rulings. Since judges are not allowed to rule independently, Western efforts to foster rule of law by training them are thus largely pointless.

Ignoring this system leads to misunderstandings of major news events. When China was hit in 2002 by the outbreak of the SARS virus, the government tried to cover up the epidemic but eventually fired the health minister, an act that was intended to demonstrate a serious change in China—for once, an official was being held accountable and sacked after a public outcry. In fact, as McGregor notes, the minister was just a scapegoat. The real decision to cover up the outbreak had been made by a leading Party group, of which the minister was just a member. None of the other Party officials were held accountable—indeed, the existence of the leading group was never mentioned. The entire blame was laid on the government minister.

Advertisement

A parallel system on this scale requires a vast army of cadres, and the Party has 78 million members—almost as many as the entire population of Germany. In theory, members vote to select their representatives in the system, culminating in the nine-man Standing Committee of the Party’s Political Bureau, or Politburo. In fact, bodies higher up in the system usually present lower-ranking members with preapproved slates of candidates. That means the system is self-selecting, with leaders trying to promote people loyal to them so they can advance their own agendas. The result is that the Party consists of factions grouped around leaders, and divisions in the Party have often been deep and venomous.2

McGregor’s book has a number of strengths, including clear prose and careful analysis. His bold and direct writing leads to striking comparisons, as when he says that the reach of the Party’s Organization Department is so expansive that it would be like one group in Washington naming the members of the Supreme Court, all the members of the Cabinet, the editors of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, the heads of all major think tanks, and the CEOs of major companies like General Electric, Exxon-Mobil, and Wal-Mart. These analogies, while imperfect, help make this an accessible introduction to the Party’s power in today’s China.

While McGregor’s writing is vigorous, the Party’s secretiveness robs the book of characters and scenes. He notes in an afterword that he is envious of reporters of US politics, who can ride on the same plane with the president and get fly-on-the-wall details—virtually impossible in reporting on the Chinese Communist Party, even for a talented reporter like McGregor. As enterprising as he may be, the result is still a book with almost no deeply interesting characters or vignettes of how they exercise power. In the end, we don’t really learn what the needlessly breathless subtitle promises—to tell us about the “secret world” of the country’s rulers.

At times, McGregor also overcompensates for the lack of colorful detail by blowing up small anecdotes. One is the somewhat implausible and unsourced claim that every single top boss in China’s big companies has a “red machine”—a sort of Batman-like hotline to the Party. Unclear from the passage is who the executives talk to on the other end or why the Party would need such a crude leash for some of its most trusted lieutenants (who are the only people allowed to run such companies).

This highlights how even today the Party is still only understood through small slivers of access or insight. The sometimes vicarious ways that insights can be gleaned is wonderfully captured in Richard Baum’s China Watcher: Confessions of a Peking Tom. A professor at the University of California–Los Angeles, Baum has written a funny and insightful memoir that looks back at more than forty years of China watching. Unlike McGregor, Baum began his work when China was closed to outsiders. His big break was pilfering secret Communist Party documents that a Taiwanese intelligence agency had stolen from the mainland. By analyzing the documents, Baum helped explain the origins of the Cultural Revolution by showing the split that had developed between Mao Zedong and his lieutenants. Like McGregor’s efforts, Baum’s have succeeded—his initial analysis of the split in leadership is still accurate decades later. But the story also shows how random our access to the Party’s inner workings is; huge aspects of its current operation and even its key historical moments are unknown, despite the existence of leaked documents.3

Interestingly, both Baum and McGregor end their books with ruminations on the Party’s abuse of history. McGregor talks to a courageous historian who helped piece together a history of the Great Leap famine of the early 1960s. Like many journalists, McGregor sees such catastrophes as the Party’s weak point and implies that it faces a reckoning with history. Baum agrees and refers to a leitmotif of Chinese philosophy and history: Confucius’s call to “rectify the names,” in other words, to call things as they really are. That would involve, for example, revisiting the Tiananmen massacre and admitting that the Party, not the protesters, was largely responsible for the violence.

Focusing on these abuses, however, can lead to a sentimentality that clouds judgment, as David Shambaugh notes in China’s Communist Party: Atrophy and Adaptation. In a sobering but illuminating section, Shambaugh surveys the prognostications that leading Western China experts have made about the Party over the past two decades. Almost all were pessimistic and almost all were wrong. Most argued that the Party was hopelessly out of touch with China’s dynamic society and was doomed to failure. One even predicted its demise to the year (this year, in fact).4 Like McGregor and Baum, many were outraged at the Party’s recent actions—especially the Tiananmen Square massacre. They may be forgiven for a bit of wishful thinking, but Shambaugh convincingly points out that the West has consistently underestimated the Party’s ability to adapt and thus might be excessively negative about its future.

Shambaugh’s book is essentially the missing historical background to McGregor’s, and in some ways it is no less exciting to read. He argues that for the Party, the turning point was indeed 1989, not only because of the Tiananmen uprising but also the collapse of communism elsewhere. This forced the Party to undertake genuine political reform efforts—not reform in the sense of democracy, which is how Westerners usually see it, but in its apparatus and how it interacts with society. In the two decades since then, the Party has trained hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of low- to mid-level officials to make them familiar with the workings of the market economy, abolished many taxes on farmers, reduced restrictions on religious organizations, and enormously increased the standard of living of scholars, students, and others who protested in 1989.5 It also has largely withdrawn from the personal lives of Chinese citizens, allowing them to pursue their own ambitions and goals as long as they avoid the high crime of directly challenging the Party. This emasculates political life but leaves much else wide open. Thus debates inside and outside the Party are permitted on topics such as the growing rift between rich and poor.

From the Party’s perspective it pulled off a surprising feat in 2002 by organizing an orderly transfer of power that wasn’t driven by a crisis like Tiananmen or the Cultural Revolution. Unless a completely unforeseen series of events takes place in the next two years, it is likely to do the same in 2012, with the odds favoring Xi Jinping becoming China’s next leader. This shows that the Party has figured out the sort of institutional stability that largely eluded its counterparts in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc.

This is essentially the view of the Party from its think tanks and training establishments. Shambaugh has culled a great deal of background on how these institutions fed information to the Party and how it responded, mainly by bulking up and curbing the worst of its excesses. Curiously, after describing all these reforms, Shambaugh concludes with a pessimistic prognosis for the Party’s prospects. The main problem, he believes, is that it can’t escape Samuel Huntington’s classic model of rising expectations and the accompanying demands for political channels by which members of the public can make their wishes known. Accepting such levels of popular participation would require a huge change in mentality for a party that for six decades has acted mainly as a development dictatorship, cajoling the nation forward. As it has ditched the utopianism of its first thirty years of rule in favor of the conventional mercantilist policies of its past thirty, the Party has also developed an ability to listen to complaints and make adjustments, while not seriously countenancing public participation.

Shambaugh also identifies a vacuity in the national ideology. Although the country’s leaders have offered up ideas, he says no unifying vision really inspires the vast nation of 1.3 billion. Traditional Chinese culture might suffice for the majority-Chinese population, but what of the fifty-five other ethnic groups, such as Tibetans, Uighurs, Dai, and Mongolians? Although these groups make up less than 10 percent of the population, they are concentrated in key border regions that have seen major protests in recent years. Some sort of national reevaluation is needed to make the country’s aims more inclusive and idealistic.

Instead, today’s leaders still follow the same basic bottom line that was first enunciated in the “self-strengthening” movement of the 1870s: attaining wealth and power, enhancing nationalism and international dignity, preserving unity and preventing chaos. As Shambaugh notes, this puts today’s Communist Party rulers in a long line going back not just to Deng and Mao but also to the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, the early-twentieth-century strongman Yuan Shikai, and the nineteenth-century self-strengthener Li Hongzhang. That in itself is a kind of legitimization but the goals are ultimately those of national survival. Once that has been assured, the vision becomes purely materialistic—economic growth.

For thirty years this has worked, but the next stage of economic development requires a more open economic and social system that can foster innovation and creativity. One badly needed reform would be to loosen the Party’s system of controlling business—the very structures that it has labored to build up over the past two decades. These tight ties between politics and economics have created giant state-owned companies that have had spectacular success on foreign stock markets. In early July, for example, China boasted the largest stock offering in history, the $22 billion listing of the Party-run Agricultural Bank of China. But these behemoths have sucked up much of the wealth created over the past decade, leaving the public with less of a share of the national output than in the past.

More tragically, this national sacrifice hasn’t really created truly outstanding and innovative international companies. The big companies that are listed abroad are indeed giants but mainly because of their sheer size; they are essentially little more than partially privatized quasi monopolies—big telecoms, banks, and insurance and oil companies. That makes them large but not particularly nimble, inventive, or influential in international markets, except when trying to buy natural resources.

Nor have the other companies routinely touted as international players—for example, the appliance maker Haier or the computer giant Lenovo—truly become global forces. Early on in its reign, the Party pushed get-rich-quick schemes like the Great Leap Forward that resulted in national catastrophe. These utopian plans are gone but more than a faint echo remains in the desire of Chinese companies to shortcut the painstaking process of creating international brands by buying faltering names.

The failure of Lenovo to leverage IBM’s brand after purchasing its personal computer business in 2005 casts doubt on the wisdom of such corner-cutting maneuvers. One can only assume that they appealed to officials looking for quick solutions to the Party’s call to create international Chinese brands. Independent boards of directors might have thought differently and pursued the more patient strategy followed by other East Asian companies.

Even then, companies would run up against another problem: the lack of creative and intellectually ambitious students. After Tiananmen, the government channeled huge sums into better dorms for students, housing for teachers, labs for scientists, and junkets for administrators. This satiated material demands and attracted foreign universities hoping to set up programs in China. But it can hardly be a coincidence that this system has never produced a Nobel Prize winner; even among China’s elite universities, the academic level resembles that of an average US land-grant university, with most no better than a mediocre community college.

Blaming the Party for all these problems would be unfair, but it is legitimate to ask if any one party in the world could solve them. Back in the 1990s, a charismatic premier, Zhu Rongji, ran China. When he was in charge, it was possible to believe that the system was perfectible, that with just the right brilliant person at the center, nothing was impossible. And this was indeed the time of a great many reforms: the state sector shrank, the country made ambitious pledges of economic changes to gain entrance into the World Trade Organization, and sprouts of civil society—including class action lawsuits and rural elections—were to be seen across the country.

Since then, the technocratic state that Zhu personified has grown stronger but in some ways more brittle. Economic reforms haven’t quite ground to a halt but the state sector is regaining lost ground, in part owing to the current administration’s policy of recentralizing control. Foreign policy, for all the international efforts to engage China on global issues, remains focused on two narrow concerns: territorial issues like Taiwan and Tibet, and resource extraction in Africa or Central Asia. And the state has become so adept at political control that no one seriously argues that civil society is becoming more robust; on the contrary, the Party’s new-found confidence has allowed it to roll back gains of previous years.

None of that threatens the Party in the near term, but this means it also lacks the impetus to reform. With China on top of the world, the Party’s perch atop the country seems impregnable and yet more vulnerable than ever.

—Beijing, September 1, 2010

This Issue

September 30, 2010

-

1

Unfortunately, McGregor does not explain much about these groups, or indeed much of the Party’s history. They have been better described in the works of Victor Shih at Northwestern University, including his Factions and Finance in China: Elite Conflict and Inflation (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Their membership is also discussed in the China Leadership Monitor, run by one of the preeminent China watchers, Alice Miller. Its quarterly issues are available at [www.hoover.org/publications/china-leadership-monitor](http://www.hoover.org/publications/china-leadership-monitor). ↩

-

2

See, for example, China’s New Rulers by Andrew J. Nathan and Bruce Gilley for a look at the maneuvering surrounding the 2002–2004 change of power from Jiang to Hu, or the recent autobiography by former Party leader Zhao Ziyang, Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang (Simon and Schuster, 2010). The new heir apparent, Xi, may be the victim of such a split: he is not Hu’s chosen successor as president but the choice of Hu’s predecessor, Jiang Zemin. Some Pekingologists speculate that Hu is purposefully weakening Xi by denying him a place on the military commission; this way, Hu could maintain his influence when he retires. ↩

-

3

Some of the key points in history that still need to be addressed include how many people died in the Great Leap famine, reckoned to be the worst in history, or the circumstances surrounding the death of Mao. See Perry Link’s “[Waiting for WikiLeaks: Beijing’s Seven Secrets](/blogs/nyrblog/2010/aug/19/waiting-wikileaks-beijings-seven-secrets/),” NYR Blog, August 19, 2010. ↩

-

4

See Gordon G. Chang, The Coming Collapse of China (Random House, 2001). ↩

-

5

Jeffrey Wasserstrom also concisely lays out these points in a lively and vigorous primer on modern China, China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know. He argues that the Party avoided “Leninist extinction” because—paradoxically—it now allows so many protests. Estimated to number 230,000 during 2009, they act as safety valves and almost all are resolved peacefully by addressing protesters’ concerns and—now only as a last resort—through coercion. ↩