The loyalists of the American Revolution, that is, those who remained loyal to the British crown during the Revolutionary War, have not gotten much of a fair shake from historians. They were, after all, the losers in the Revolution, and history is usually not kind to losers, especially exiles or refugees from a lost war. Usually, but not always. History, or at least popular memory in folk songs and poems, has continued to remember the seven thousand French Acadians forcibly exiled from their homes in Nova Scotia by the British during the French and Indian War in the mid-eighteenth century and scattered throughout the thirteen British colonies. History also has never forgotten the losing efforts of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Scottish Jacobites of 1745 to restore the Stuarts to the British throne. And the “lost cause” of the South in the Civil War was kept alive for decades and is still not completely dead. Still, as Maya Jasanoff points out in this spirited and engaging book, for over two centuries the story of the loyalist exiles from the American Revolution has been largely ignored—until now.

Jasanoff, who is professor of history at Harvard and author of a highly regarded work, Edge of Empire, that dealt with the ways in which British and French individuals experienced the culture of empire in India and Egypt, has turned her remarkable historical talents to the experiences of the tens of thousands of loyalists who felt compelled to leave the North American colonies that became the United States and migrated, sometimes moving from place to place, to both near and distant parts of the rapidly expanding British Empire. Jasanoff rightly claims that her book provides “the first global history of the loyalist diaspora.”

The American Revolution had international consequences that went beyond spreading the ideas of democratic republicanism. Indeed, Jasanoff persuasively contends that “the 1780s stand out as the most eventful single decade in British imperial history up to the 1940s.” What she calls the “spirit of 1783” that emerged out of the peace treaty with America animated the renewed British Empire well into the twentieth century. Ultimately, she says, it had more worldwide significance than the “spirit of 1776.” This “‘spirit of 1783’…provided a model of liberal constitutional empire that stood out as a vital alternative to the democratic republics taking shape [in this period] in the United States, France, and Latin America.”

The events of the 1780s created an enduring framework for the spread of the principles of British centralized hierarchy and liberal humanitarianism to the farthest reaches of the globe. It was Britain that defeated Napoleon and stood for ordered liberalism against the reactionary forces of the Holy Alliance. It was Britain that backed up the Monroe Doctrine and prevented conservative Europe from reconquering the New World. It was Britain that led the world in the abolition of slavery. And it was British ships that scoured the seas and enforced the ban on the international slave trade. According to Jasanoff, the loyalist exiles played an important part in this nineteenth-century expansion of the liberal British Empire, a worldwide expansion that more than compensated for the loss of the North American colonies. It was even an American loyalist, James Mario Matra, who put forward the first serious proposal to colonize Australia.

The loyalists were the losers in what was clearly a civil war. Americans have been generally reluctant to admit it was bloody fratricidal conflict. At least a fifth and maybe as many as a third of the two and a half million British colonists in 1776 opposed the break from Great Britain. They suffered greatly for their loyalty to the king—their property was confiscated and they were intimidated by mobs, tarred and feathered, and assaulted and brutalized to a degree not often described by American historians. At least 19,000 of them joined provincial regiments to fight their fellow Americans in the long and bloody war.

At the same time the Revolution also divided the native peoples. While the Mohawks, for example, sided with the British, the Oneida Indians joined the American rebels, and in the end both Indian nations suffered. The white loyalists were not the only losers. About 20,000 black slaves, including almost two dozen belonging to the author of the Declaration of Independence, fled to the British lines with the promise of freedom, resulting, writes Jasanoff, in “the largest emancipation of North American slaves until the U.S. Civil War.”

By the end of the conflict in 1783 tens of thousands of loyalists and slaves had moved for safety to New York and other cities dominated by British troops. Of these about 60,000 chose to leave the United States along with the 35,000 British and Hessian soldiers. Evacuating these numbers of people in a short period of time was unprecedented, and the process made Britain’s dismantling of its American empire even more difficult. In New York, Savannah, and Charleston, British officials not only had to wind down the empire but also had to cope with shortages of food, rum, ships, and cash, and the clamors of thousands of loyal civilians seeking relief and reassurance.

Advertisement

Where would the loyalists go and what would be needed to get them settled? Would the loyalists in Charleston and Savannah be allowed to bring their slaves with them? Would the British have to compensate the Americans for the freed slaves they were taking with them from New York? Jasanoff describes all of these problems clearly and coherently, and demonstrates that, despite a multitude of mistakes, the evacuation of tens of thousands of people from North America over a mere matter of months was extraordinarily well handled and a tribute to the efficiency and humanity of the British officials, especially Guy Carleton, the commander in chief of the British forces in North America.

Carleton was particularly angered by Article V of the Treaty of Paris signed in 1783, which stated that Congress would merely recommend to the states to restore the confiscated estates and properties belonging to “real British subjects.” Since the states hadn’t been very conscientious in following recommendations of Congress, the loyalists regarded this infamous article, writes Jasanoff, as “the greatest betrayal of their interests.” At the same time the treaty also pledged that the British would not carry away “any Negroes, or other Property” of the American inhabitants. Despite this apparent prohibition against the British taking away American slaves, Carleton insisted that slaves promised their freedom should have it. He took this principled stand not because he was an abolitionist but because he felt Britain’s honor in keeping its word was at stake.

When General Washington first met Carleton in May 1783, he immediately lectured the British commander on what seemed to be the most urgent matter on his mind—the British removal of human property from New York. When Carleton calmly told him that a fleet had already embarked for Nova Scotia with registered black loyalists on board (including a slave that had once belonged to Washington), the American commander in chief was stunned. “Already imbarked!” Washington exclaimed, and he protested vehemently. But as Jasanoff describes the incident, Carleton matched Washington’s impassioned accusations of miscarriage point for point, “meeting outrage with moral superiority.”

The loyalists went everywhere in the British Empire. About eight thousand whites and five thousand free blacks traveled to Britain itself. Although the loyalists had been raised to consider Britain as “home,” most of the refugees, even those who were privileged, soon discovered that they were strangers in a strange land. What the white refugees wanted most was compensation for their losses. After much hard lobbying by the loyalists, the government actually established a Loyalist Claims Commission to hear requests and make reparations.

Britain had had refugees before—50,000 French Huguenots in the late seventeenth century and 13,000 Palatine Germans who fled to England in 1709. But never before had the British government accepted financial responsibility for the refugees. Like the other things the British government provided the loyalists—land grants, free passages, rations and supplies—awarding compensation for losses was truly remarkable, all part of the British government’s Atlantic-wide program of refugee relief. The government never believed that the loyalists had a right to reparations; instead, it assumed that Britain had a moral and paternalistic responsibility to provide aid to its loyal subjects.

In the end 5,072 people from all over the empire submitted claims of some sort, and the commission examined 3,225 in full, creating the largest single archive of evidence about the loyalists. The records show that they came from all levels of American society. Four hundred and sixty-eight of the 3,225 claimants were women and forty-seven were black men. Some three hundred claims were made by people who could not sign their own names. The commission set up a bureaucratic apparatus to examine the claims and required a high level of evidence and documentation in order to win compensation. The result was that those with connections received the most money. In the end 2,291 loyalists were awarded £3,033,091 out of claims totaling £10,358,413; an additional 588 received pensions as compensation for lost income.

Although the commission shortchanged many of the black and poorer loyalists, it nonetheless stood as an unprecedented example of large-scale charitable relief by a government that was scarcely modern. Together with Britain’s increased criticism of the slave trade and its efforts to reform the East India Company and to prevent corruption and the abuse of power in its empire, the commission’s treatment of the loyalists, writes Jasanoff, “illustrated the paternalistic impulses of the ‘spirit of 1783,’ toward increasingly centralized authority and the clarified ideals of liberty and moral purpose.” These examples of British liberality and humanitarianism helped to reinvigorate the empire, coupled as they were with administrative reforms designed to ward off colonial discontent from Ireland to India. Edmund Burke reminded his fellow members of Parliament that the loyalists had no claim for compensation on grounds of right; instead, Britain was bound by honor to consider the claims. Compensating the loyalists did “the country the highest credit…. It was a new and noble instance of national bounty and generosity.”

Advertisement

Jasanoff suggests that Burke’s speech and his use of the word “new” together with the peace treaty’s reference to “real British subjects” implied that in the post-revolutionary empire the overseas subjects would no longer be considered as equivalent to Englishmen in the metropolis—precisely the equivalency that the American colonists had claimed during the imperial crisis leading up to the Revolution. Instead, the overseas subjects would now be clearly different; they would still be subjects, but ones for whom British officials would be paternally and morally responsible. The treatment of the loyalists had changed the nature of the empire. “Thanks to the Loyalist Claims Commission,” says Jasanoff, “loyalists had gone from reminders of defeat to points of pride, testaments to British munificence.”

In the meantime loyalist exiles were being settled everywhere in the empire. Over 30,000 left for Nova Scotia and Quebec, with most settling in Nova Scotia, which soon split, creating the new province of New Brunswick. “Nowhere,” says Jasanoff, “did loyalist refugees transform their surroundings on the same scale or with the same enduring significance as in the provinces of British North America.” They helped to transform regions once heavily French to the English-dominated Canada of today. With the white population of Nova Scotia overwhelmingly composed of refugees, the province became the only place the loyalists could claim as their own state, and they set about fashioning it as an imperial alternative to the rowdy nation to the south. “Yes—By God! We will be the envy of the American States,” reported loyalist Edward Winslow.

But the loyalists had been reared in America, and, according to Jasanoff, they tended to bring American attitudes with them, including attitudes about popular representation, land distribution, and racial animosity. The result was a series of clashes between the loyalists and the British authorities and among the loyalists themselves. “Armies in the streets, unlawful arrest, unfair taxation, unjust elections: the scene [in Saint John, New Brunswick],” says Jasanoff, “might as well have come straight out of the thirteen colonies on the eve of the revolution.” But this time the imperial authorities put down the defiance and disorder. Although the loyalists had a variety of political views, they agreed on one thing: upholding the authority of the king. “In this key respect, loyalists were loyal; and this,” says Jasanoff, “was one vital reason why the government did prevail.”

Jasanoff is eager to demonstrate that the Canadian loyalists were not all that different from the American patriots. Most of them, she says, cannot be dismissed as reactionary “tories.” Yet she is not quite able to explain why they thought and acted as they did, except to say that they were distinguished from the American patriots by their persistent loyalty to the king. This seems to be begging the question rather than answering it.

While most of the loyalists evacuated from New York went to Canada, those leaving Charleston and Savannah tended to go to southern parts of the British Empire. By 1783, 12,000 loyalists and their slaves from Georgia and South Carolina had already settled in East Florida, which Britain had acquired from Spain at the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Suddenly, these loyalists were shocked to learn that Britain had agreed to cede East and West Florida back to Spain, with no provision for their presence. Unless these loyalist refugees were prepared to swear allegiance to the king of Spain and practice Catholicism, they had eighteen months to gather their possessions and move on. “We are all cast off,” complained one embittered loyalist. “I shall ever tho’ remember with satisfaction that it was not I deserted my King, but my King that deserted me.”

Throughout 1784 and 1785 most of these loyalists and slaves left East Florida. Several thousand were thought to have slipped over the mountains back into the United States. Nearly ten thousand others, including slaves, were dispersed around the Atlantic, especially to the British islands in the Caribbean where thousands of loyalist migrants from Georgia and South Carolina had already settled. By 1785 some 2,500 white refugees with their 6,000 slaves made up the population of the Bahamas. Led by the maniacal John Cruden, some of the loyalists plotted to use the Bahamas as a staging ground for bringing parts of North America back into the empire. Others of these doubly displaced loyalists were angry enough at the discrepancy between their expectations and the reality of settlement in the Bahamas to protest with armed mobs and riots, American style, against the royal authorities. They complained not just about provisions and land allocation but political representation.

Jasanoff uses these protests to reaffirm her questionable argument that most of the loyalists remained Americans at heart. The problem with her argument is that even Englishmen in the metropolis tended to behave in this riotous fashion. Indeed, the British people in the eighteenth century had a notorious reputation for being rowdy and ungovernable. So the brawling, liberty-loving loyalists may have been behaving not as revolutionary Americans but as defiant but ultimately loyal Britons.

Jasanoff devotes a chapter to the three thousand loyalists and their eight thousand slaves who ended up in Jamaica, an already settled British colony—indeed, the wealthiest jewel in the empire. Moving into an existing society of 18,000 white Creoles and 210,000 slaves, the white loyalist refugees were a tiny minority within the white minority of Jamaican society. Unlike Canada and the Bahamas, heavily settled Jamaica had no spare land for the refugees. With no use for their slaves, some of the white loyalists sent them back to the States to be sold. Those black refugees that remained in cities on the island found themselves, probably for the first time in their lives, in circumstances where black faces outnumbered white.

One such black loyalist was George Liele, a free but indentured black from Georgia. Born a slave, Liele had been granted freedom by his loyalist master. He had become an itinerant Baptist preacher in Georgia, and on Jamaica he continued his preaching and founded the island’s first Baptist church in Kingston. When the slave rebellion on Saint-Domingue broke out in 1791, slave-holding whites everywhere became frightened and tightened up their sedition laws. As a free black preacher, Liele was suspect, and in 1794 he was jailed for expressing seditious sentiments. When the charge of sedition failed to stick, Liele was imprisoned for three years for indebtedness. When released he never preached again.

Since Jasanoff could not tell the stories of 60,000 loyalists in one volume, even if the records allowed her to, she decided “to focus on the cluster of figures who capture different varieties of the refugee experience.” George Liele was one of these. But there were many others whom Jasanoff brings alive. Indeed, one of the strengths of her deeply researched book is the extent to which she was able to recover the stories of some of these loyalist refugees.

One of the most interesting and poignant of these stories is that of Elizabeth Lichtenstein Johnston. Born in 1764, she lost her mother at age ten and spent the Revolution in seclusion while her father fought in a loyalist regiment. In 1779 she married William Martin Johnston, a loyalist army captain and medical student. When Savannah was evacuated in 1782 she moved to Charleston with a young son in hand, eight months pregnant, and only eighteen years old. Six months later Charleston was evacuated, and the Johnstons moved to East Florida where Elizabeth bore her third child. But when the province was returned to Spain, they sailed to Edinburgh in 1784 where her husband completed his medical education. There she had her fourth child, having given birth to four children in four different cities in about as many years. Not happy in Scotland, the Johnstons in 1786 moved to Jamaica, where Elizabeth bore five more children. She lost one child in Edinburgh and two more in Jamaica.

In 1796 the Johnstons made the difficult decision to have a “debilitated” Elizabeth return to Scotland with the children while her husband remained in Jamaica practicing medicine, which, given the death rate among whites on the island, was much needed. In 1802, learning that her husband was ill, Elizabeth returned to Jamaica. But after the Johnstons lost another child to yellow fever, William in 1806 decided to ship his wife and the rest of his family off once again, this time to Nova Scotia. “Send us to Nova Scotia!” Elizabeth cried when she learned of her husband’s decision. “What, to be frozen to death? Why, better send us to Nova Zembla [in Baffin Bay], or Greenland.” But she was wrong. William remained on the disease-ridden island of Jamaica and died the following year, while Elizabeth and her family flourished among the many loyalist-dominated communities of icy Canada.

The Johnstons were not the only loyalist exiles whose lives were marked by repeated migrations. Jasanoff tells the story of several imperial officials who moved and served throughout the empire. John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, was the last royal governor of Virginia. He became a notable advocate of loyalist interests and promoted various schemes to continue the war. He became governor of the Bahamas in 1786, in which capacity he supported a scheme to establish a pro-British Creek state in the southwest, called Muskogee. Guy Carleton was another noteworthy imperial official. After overseeing the evacuation of loyalists from America in 1782–1783, Carleton, newly ennobled as Lord Dorchester, returned to Quebec in 1786 as governor in chief of British North America, where he remained until 1794. His younger brother Thomas Carleton was governor of New Brunswick from 1784 to 1817. Epitomizing the trajectory of the empire as it discovered success despite losing the American colonies was the career of Lord Cornwallis, the defeated general at Yorktown, who ended up as governor-general of Bengal in India.

Perhaps the most fascinating of Jasanoff’s stories belongs to David George. Born a slave in Virginia, George ran away in 1762 and after several escapades ended up in the custody of an Indian trader in South Carolina. Partly under the influence of George Liele, he converted to Baptism. He followed British forces to Savannah and continued to preach with Liele. George and his family joined the British evacuation from Savannah and traveled to Nova Scotia as free black loyalists. There he became an active evangelist, establishing a church at Shelburne in Nova Scotia and preaching to both white and black congregations throughout the area. As blacks became increasingly unhappy with their circumstances in Canada, George in 1791 emerged as one of the supporters of the project to settle African-American loyalists in the West African area of Sierra Leone.

Early in 1792 about 1,200 black loyalists from Canada, about a third of all the free blacks in the Canadian provinces, sailed for Africa in what was one more migration by refugees who seemed constantly on the move. The settlement in Freetown in Sierra Leone, which Jasanoff calls “the first ‘back to Africa’ project in modern history,” was marked by the same contentiousness that plagued other loyalist settlements—disputes over land allocation, taxes, and political representation. In 1800 the black settlers, including Harry Washington, who had run away from Mount Vernon twenty years earlier, but not David George, rebelled, but they were quickly put down by the white authorities. The Sierra Leone Company settlement was turned into a crown colony administered directly from London. Yet in the end the colony at Freetown represented another expression of the “spirit of 1783,” another example of Britain’s attempt to combine centralized authority with liberal humanitarianism. Freetown survived and grew.

As the American Revolution of a previous century receded in memory, many of its loyalists had become assimilated into the new British Empire. Not only did the War of 1812 demonstrate that the North American loyalists in Canada had become part of a new nation, but some of the loyalists carried their “spirit of 1783” all the way to India. Partly out of defeat the British had created the sources of the greatest empire the world had ever seen.

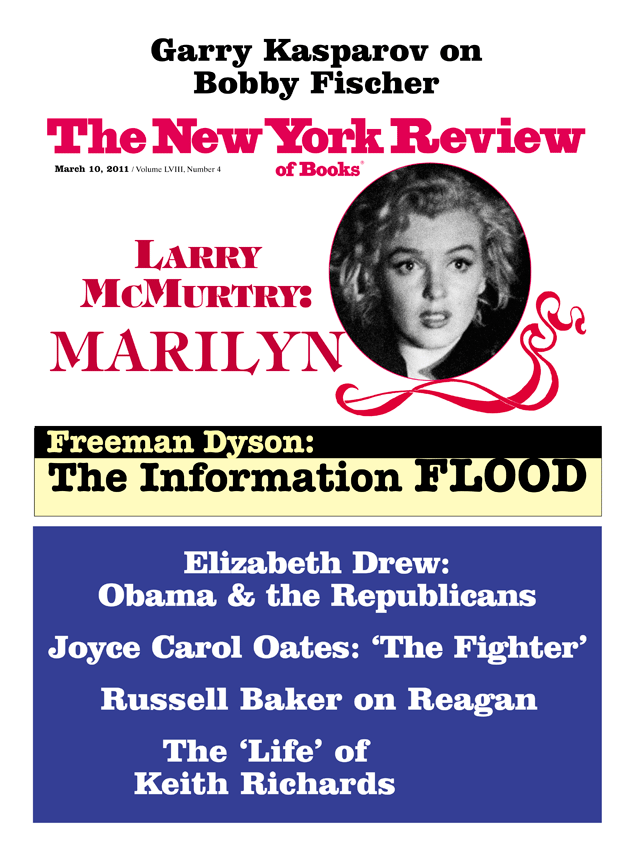

This Issue

March 10, 2011

Marilyn

The Bobby Fischer Defense

How We Know